Iranian Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age

After ending "First Great Migrations", the Slavic, Baltic, Germanic, and Iranian tribes stayed near the places of their primordial habitats. Further study of the ethnogenesis of these peoples requires further application of the graphic-analytical method. Using this method for the Germanic and Baltic languages is problematic because of their small number, so we must start with Iranian or Slavic. Following the chronology, it is necessary to begin with Iranian

The history of the Iranian languages is very difficult to reconstruct due to mutual influences, and borrowings from Arabic and Turkic. The issue is also complicated by the absence or insufficiency of written monuments and the fact that some languages remain unwritten or poorly written. We can confidently talk about the development of the Persian language (Farsi), whose history can be traced back to the VI century. BC, about its close connection with Tajiki, as well as about the continuation of the Sogdian language in modern Yaghnobi. Even the question of the dialectological affiliation of the Avesta language still has no unambiguous answer (ORANSKI I.M., 1979: 33). There are so many Indo-Aryan forms in the Avesta language that have no counterpart in the Iranian languages that it can be considered simply a written language based on Indo-Aryan with extensive use of true Iranian words. In this regard, there is no way to connect the language of the Avesta with any modern language, because research experience has shown that quite numerous ancient peoples do not disappear, but survive under a different name and preserve their language. The same applies to the Median language, about which not a single written monument has survived (DIAKONOV I.M. 1956: 9), which does not allow us to speak about its relationship with other Iranian languages with sufficient accuracy. However, one of them may be its continuation. On the other hand, the Persian language highly influenced other Iranian languages over the centuries and the Persian loan words often displaced the original vocabulary from unwritten and little-written languages, which is now lost forever.

Specialists believe that the Iranian common language, or "base language", at some time differentiated into two main dialect groups conventionally called "Western" and "Eastern". The main features of this division are some historical and phonetic features of their consonantism. The Median, Parthian, Baluchi, Kurdish, Talyshi, Persian, Tajik, Tatic, and other languages originated from the western dialects, and the eastern dialects gave rise to the Sogdian, Khorezm, Pashto, Ossetian, Pamir languages, etc [ORANSKI I.M., 1979: 88]. Ignoring such division, we will examine Iranian languages using the graphic-analytical method and see how obtained results correspond to the accepted differentiation.

The Iranian language family includes nearly 40 modern languages (Ibid: 17). Among them are individual Ossetian (with Digor and Iron dialects), Yaghnobi, Pashto (with the dialect of Wanetsi), Yazghulami, Kurdish (with Zazaki, Kurmanji, Sorani, and Gorani dialects), Balochi, Gilaki, Mazanderani, Sarikoli, Paracha, Ormuri, the language of Semnan. Other languages are combined into groups. These are Talyshi with close to it Tati, dialects of Persian-Tajik (Farsi, Khuzestani, Bandari, Quhistani, Hazaragi, et al.), the minor languages of Central Iran, Luri and Bakhtiari dialects, dialects of Southern Iran (Bashkardi, Kumzari a.o.), Pamir languages, including Shughni-Rushan and Ishkashim-Wakhi language groups. In addition, there were still the languages of the Avesta, Bactrian, Parthian, Sogdian, and Saki-Khotanese languages and languages or dialects, not mentioned in historical sources, which can be indicated by linguistic analysis of the texts of the Avesta and ancient Persian language. The modern spread of Iranian languages says little about their ancestral relationship (see map below).

Dissemination of Iranian Languages

This map is based on work by Dr. of Columbian University Michael Izady (the original is here) .

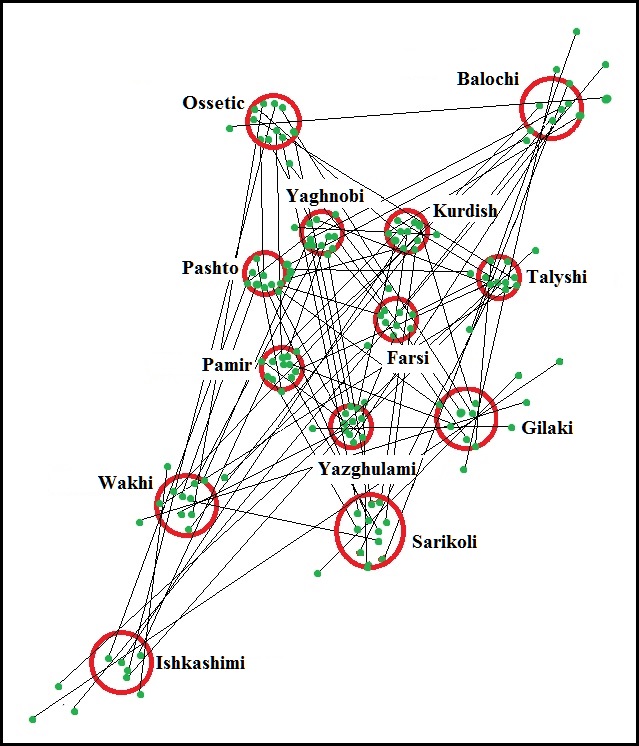

The first attempt to establish the kinship of the Iranian languages using the graphic-analytical method was made at the end of the last century (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998. 73-77). The idea of the method consists in the geometric interpretation of the relationship of related languages, or rather, constructing a graphical model of their relationship based on the calculation of common language units in pairs of languages of the studied language family or group. For the resulting model, a corresponding place on the map with fairly clearly defined boundaries of ethno-producing areas has to be found.

The most convenient for counting is vocabulary as the most numerous collection of linguistic units. For the convenience of counting, an etymological dictionary table is compiled consisting of nests of words attributed to one etymon. At that time, the etymological dictionaries necessary for compiling the table had not yet been published, except for four volumes of the Historical and Etymological Dictionary of the Ossetian Language (ABAYEV V.I. 1958-1989), therefore, the lexical material was selected from bilingual dictionaries of Ossetic, Kurdish, Talishi, Gilaki, Persian, Pashto, Tadjik, Dari, Yazghulami, Shughni, Roshani (with Khufi), Bartangi, Yaghnobi, Sarikoli (Tashkorgani). Data on the basic patterns of phonetic correspondences between Iranian languages were taken from the works of Sokolov [SOKOLOV S.N. 1979: 127-235], the features of Talysh consonatism were taken into account according to Miller's work [MILLER V.V. 1953: 53-57]. The establishment of a primordial relationship between the Iranian languages was hampered by later mutual borrowings, especially from Farsi. The influence of Persian on other Iranian languages is easily explainable, but borrowings from Tajik and Dari are also common, and migrations changed the original spatial arrangement of languages, which resulted in mutual borrowings in the already-formed languages of the new neighbors. During the analysis, it was found that the artificial languages of Dari and Tajik can be combined into one language with Persian, as having a common origin. The Shughnai, Roshani, and Bartangi languages also have a common origin. They, too, were united into one group of Pamir languages. The second group of Pamir languages is Wakhi and Ishkashimi. Thus, the structure of the ancient relationships of the Iranian languages in the present is distorted and its true graphic model cannot be reproduced based on modern vocabulary with sufficient accuracy.

When constructing a diagram of the relation of the Iranian languages (see below), it was seen that for some languages lexical material is insufficient. Indeed, some of the dictionaries used were quite small. This is especially true for the dictionary of the Gilan language, the lexical composition of which is still insufficiently studied. (KERIMOVA A.A., MAMEDZADE A.K., RASTORGUYEVA V.S. 1980: 4). However, an approximate diagram of the relationship was drawn up without much effort under certain conventions – where the data of some pairs of languages contradict, the data of other pairs come to the rescue. This is a peculiarity of the graphic-analytical method.

At left: The initial graphic model of the relationship of the Iranian languages

In principle, the resulting scheme should correspond to the location of the areas of formation of the studied languages. The experiment carried out with deliberately distorted data with a relative error of 40% showed that the construction of a scheme is possible, and it practically does not differ from that obtained from the correct data (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 19-21).

Thus, errors in the data do not distort the existing regularity in the lexical structure of languages that arose at the initial stage of their formation, and this structure is not violated in the process of its further development. The very construction of the language kinship model speaks of the preservation of the primordial regularity in the data used.

Specifically, in our case, the borrowings not eliminated from the dictionary table had a haphazard nature and therefore could not significantly distort the structure of kinship of the Iranian languages. The undoubted difference between the obtained model and real relationships is due rather to the incompleteness of data for some languages than to the influence of borrowings.

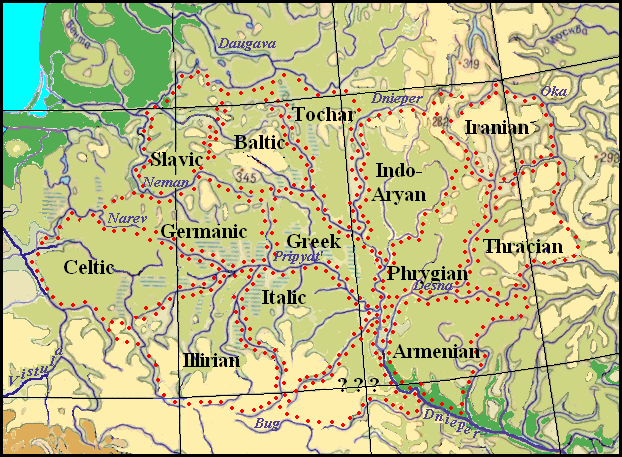

The ancestral home of the Iranians was determined after studying the relationship of Indo-European languages using the graphic-analytical method. On the common Indo-European territory, the Iranians occupied an area between the Desna and the Oka rivers, bounded in the north by the Ugra River, and in the south by the Zhizdra (see the map below).

The common Indoeuropean territory in the Dnepr basin

When, during the "First Great Migration", the Indo-Aryans, Phrygians, Thracians, and Armenians left in search of new places of settlement, the Iranians began to populate their deserted areas and significantly expanded their territory (see the map below). Continuing their movement to the south they occupied the Azov steppes between the Dnieper and the Don. In this vast space, in the ethno-producig areas, the division of the common paternal Iranian language took place.

At right: The ancestral home of the Iranians and the direction of migration of Indo-European tribes.

After the publication of the first volumes of the Etymological Dictionary of Iranian Languages, etymological dictionaries of the Kurdish and Wakhi languages (STEBLINE-KAMENSKY I.M. 1999; RASTORGUYEVA V.S., EDELMAN D.I. 2000-2004; EDELMAN D.I. 2011-2015; TSABOLOV R.L. 2001, 2010), it became possible to compile the dictionary-table of Iranian languages based on more reliable lexical material. However, the “reliability” remained rather conditional, which was also realized by the compilers of the dictionaries, who faced insurmountable difficulties:

We have… to put up with the inevitable gaps explained by failure known material of a language (eg, lack of fixing words in the texts of the extinct languages, the lack of dictionaries of some living languages and dialects), or the loss of a word in any language by replacing it by an innovative word or borrowing (EDELMAN D.I. 2005: 8).

On the other hand, the compilers of the dictionaries proceeded from traditional, but to a certain extent erroneous, ideas about the history of the development of the Iranian languages. In particular, they did not question the existence of the Indo-Iranian linguistic community, which turned out to be fiction, which became clear when studying Indo-European languages using the graphic-analytical method. As a rule, when compiling a dictionary, a word from the Avesta was taken first, assuming the existence of a similar word in Old Iranian. Correspondences were found for it in Indo-Aryan and other Indo-European languages, and based on their comparison, an alleged ancient Iranian root was formed, to which matches were sought in modern Iranian. The possibility of the existence of Old Iranian words without correspondences in the Indo-European languages was not assumed. If such words were present in only a few languages, they were mostly ignored a priori and taken for borrowing. However, borrowings are different. Some of them may date back to the formation of the language and therefore may be original, even if their roots are not Indo-European. The conspicuous excessive disproportion between the volumes of original words taken for analysis from different languages could not take place, since their primary carriers stood at the same level of cultural development, and this should have been reflected in languages. Following this view, the disproportion was eliminated by replenishing the lexicons of underrepresented languages due to the found correspondences in bilingual dictionaries. In addition, etymological dictionaries often contain references to a certain Scythian-Sarmatian language, which in reality never existed. For many decades, mainly through the efforts of V.I. Abayev, attempts to restore the "Scythian language" and determine its place among the Iranian ones were continuing (ABAYAEV V.I. 1965, 1979). Moreover, assuming the existence of distinct Scythian and Sarmatian languages, attempts were made to establish certain phonological regularities between them in the firm belief that both Scythians and Sarmatians spoke a language close to Ossetian. (WITCZAK K.T. 1992; KULLANDA S.V. 2005, 2016). Such "research" cannot be perceived otherwise than as scholasticism (see Scythian Language). Naturally, the references of the authors of the dictionaries to the Scythian-Sarmatian language were ignored.

Considering all these peculiarities, a new Iranian etymological table-dictionary was compiled among 1674 lexical nests. It was entered into the general database "Stwal". The list of Iranian languages taken for the study and the number of common words in the language pairs are given in Table 1. The number of words in each language is shown diagonally in the table.

Table 1. Quantity of mutual words in pairs of the Iranian languages

| Language | Bal. | Oss. | Kurd. | Yagh. | Pash. | Farsi | Shug. | Yazg. | Tal. | Sar. | Gil. | Wakh. | Ishk. |

| Balochi | 308 | 10 | 6,5 | 7,3 | 6,6 | 5,5 | 8 | 9,6 | 8,9 | 11,5 | 13,9 | 10,3 | 20,8 |

| Ossetic | 149 | 530 | 5 | 4,1 | 4,7 | 3,8 | 5,7 | 6,5 | 7,7 | 8,9 | 8,9 | 9 | 13,5 |

| Kurdish | 231 | 297 | 697 | 3,7 | 3,2 | 2,5 | 4,1 | 4,9 | 3,8 | 6,3 | 7,6 | 4,6 | 11,8 |

| Yaghnobi | 205 | 362 | 402 | 726 | 3,2 | 2,6 | 3,6 | 4,2 | 5,2 | 5,5 | 6 | 5,8 | 8,6 |

| Pashto | 226 | 320 | 458 | 455 | 773 | 2,4 | 3,4 | 4,1 | 4,1 | 5,3 | 4,4 | 5 | 8,6 |

| Farsi | 275 | 397 | 606 | 567 | 631 | 1002 | 3 | 3,6 | 3,3 | 4,7 | 5 | 3,7 | 7,7 |

| Shughni | 187 | 261 | 365 | 422 | 445 | 503 | 776 | 2,9 | 5,3 | 3,6 | 4,6 | 5,4 | 6,7 |

| Yazghul. | 156 | 229 | 303 | 352 | 368 | 412 | 516 | 644 | 6,5 | 4,4 | 5,2 | 6,3 | 7,6 |

| Talysh | 168 | 194 | 395 | 290 | 347 | 455 | 284 | 231 | 531 | 8,5 | 10,7 | 5,1 | 16,3 |

| Sarikoli | 130 | 169 | 238 | 271 | 285 | 324 | 421 | 343 | 176 | 506 | 5,7 | 8,6 | 8,2 |

| Wakhi | 108 | 168 | 196 | 251 | 276 | 304 | 327 | 288 | 138 | 261 | 465 | 11,5 | 6 |

| Gilaki | 145 | 165 | 323 | 258 | 302 | 402 | 277 | 239 | 292 | 174 | 131 | 464 | 18,3 |

| Ishkash | 72 | 111 | 127 | 174 | 175 | 195 | 222 | 197 | 92 | 182 | 247 | 82 | 304 |

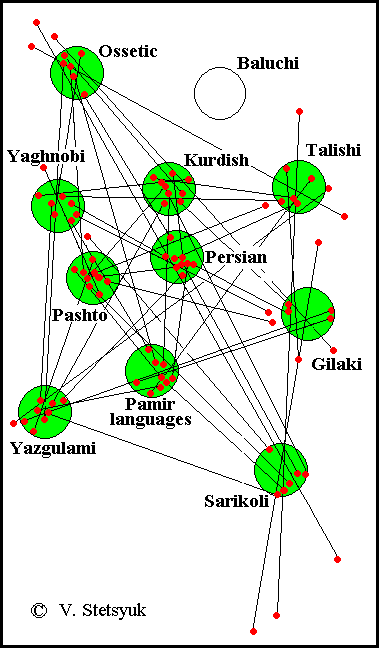

Based on the data obtained, a model of the relationship of the Iranian languages was built, which is presented in the diagram below.

The configuration of the resulting scheme as a whole should reflect the location of the areas in the common Iranian territory, in which the formation of distinct languages took place. However, the incompleteness of the vocabulary of peripheral languages, presented in the dictionary table, affected the scheme with too large distances between their areas and less accuracy of the points that define them. In this regard, the scheme does not accurately correspond to the part of the map on which it should be laid. The kinship models of the Indo-European and Turkic languages, which were formed here earlier, overlap much better, and they made it possible to highlight the ethno-producing areas on the map in which the Iranian languages could have been formed. With this assumption, the Iranian scheme can be attributed to the large space between the Dnieper and the Upper Oka and the Don, up to the shores of the Sea of Azov.

The upper part of the scheme corresponds to the map better, and when localizing it, the features of the Ossetian language are taken into account. They were noted by V.I. Abaev:

its special closeness to the languages of the European area – Slavic, Baltic, Tocharian, Germanic, Italic, Celtic. According to several features – lexical, phonetic, and grammatical – the Ossetian language, breaking with other Indo-Iranian languages, merges with the listed Indo-European languages (ABAYEV V.I., 1965: 3)

In his works, Abaev presented quite a lot of lexical correspondences between the Ossetian and Tocharian languages. Here are some of them:

Toch. ānkar "fang" – Osset. assyr "fang",

Toch eksinek "a pigeon" – Osset äxinäg "a bpigeon",

Toch aca-karm "a boa" – Osset kalm "a snake",

Toch káts "stomach" – Osset qästä "stomach",

Toch kwaš "a village" – Osset qwä "a village",

Toch menki "lesser", Lit. meñkas "little" – Osset. mingi "little, few",

Toch porat "an axe" – Osset färät – "an axe",

Toch sám "enemy" – Osset son "enemy" (А. Abayev V.I. 1965).

Toch witsako "a root" – Osset widag "a root".

However, V. Abaev believed that these matches come since the Scythian times, but the Tocharians had already moved to Asia at that time.

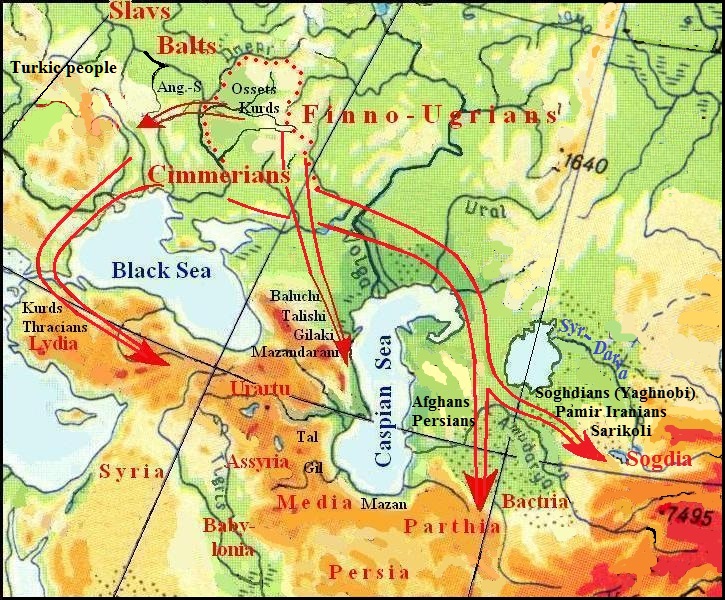

Taking into account the special ties between the Ossetian and Tocharian languages, the resulting model of the relationship of the Iranian languages should be located so that the area of the Ossetian language would be adjacent to the Tocharian language, i.e. superimposed on the ethno-producing area in the Sozh basin between the Dnieper and Iput' rivers. This determined the localization of the ethno-producing areas of the remaining Iranian languages. Their estimated placement is shown on the map below.

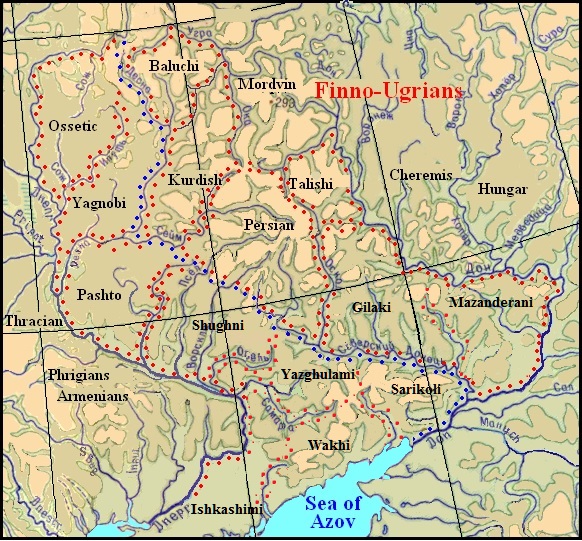

The territory of the formation of the Iranian languages in the 2nd millennium BC

On the map, the boundaries of ethno-producing areas are marked with red and blue dots. The blue dots also mark the border between the "western" and "eastern" Iranian languages. The accepted location of the Iranian areas is confirmed by revealing facts of language substratum influence of the previous population. We see, for example, that the area of the Afghan language (Pashto) is located in the same place where previously the Armenian language was formed. Thus still unexplained matches between these languages are just the result of the impact of the Armenian substrate. More information on this topic is covered in the section "Language substratum".

Following the scheme, the area of the Balochi language should be located in the ancestral home of the Iranians north of the Zhizdra River between the Desna, Ugra, and Oka rivers.

The area of the Yaghnobi language was supposed to be found in the vicinity of the area of the Ossetian, therefore it is located between the Dnieper, Iput', and Desna, and the area of the Kurdish language, close to the Yaghnobi, is between the Desna, Seim and the upper reaches of the Oka. The area of the Pashto language between the Dnieper, Sula, and Desna and the Talysh area in the upper reaches of the Oskol River on the right bank of the Don between the Sosna and Tikha Sosna rivers are also more or less well located. The area of the Persian language, located in the very center of the scheme, is bordered by the Oskol and the Seym Rivers. Its southwestern border runs along the Seversky Donets River, and further, the natural boundary to the Seym River is not seen. At the same time, the areas on both banks of the Psel River are empty. These small areas formed dialects that gave rise to some Pamirian languages, akin to Shugnan. Then the area of the Gilaki language should be placed between the Seversky Donets, Oskol, and Don Rivers. However, its south-eastern border is difficult to identify, because this depends on the location of the area Mazanderani language, which was not included in the model of relationship due to lack of data. Given the modern habitat of the Mazanderanians, their ancestral home can be assumed to be east of the Gilaki area. However, in this part of the map, two or even three areas can be distinguished, in which languages that were not included in the studied languages were formed. The Wakhi and Ishkashimi languages were to be formed on the left bank of the Lower Dnieper.

As a result, it turned out that the so-called "East-Iranian" languages are located in the west of Iranian territory and stretch along the left bank of the Dnieper River. Accordingly, the "West-Iranian" ones stretched along the left bank of the upper Oka River and the right bank of the Don, in the neighborhood of the Finno-Ugric settlements. The Seversky Donets River was a clear border between them.

Due to the lack of data for some of the modern Iranian languages and their insufficiency for others, special difficulties arise with the placement of areas for the Sarikoli, Yazghulami, and languages of the Pamir peoples. For the group of languages in which we included Shugnan, Bartangian, and Rushan there is no other place between the Vorskla and Oskol rivers. The area of the Yazghulami language should be somewhere to the south, and the area of the Sarikoli language, whose place in the kinship model is far from other languages, should have been in the Don bend. The Yazghulami and Sarikoli languages should have much more common words, but just the dictionaries of these languages were the smallest, and without a doubt, many matches in the Sarikol language have not been revealed. Its more precise placement depends on the ties with Mazandaran, the extent of which is questionable. Along the coast of the Sea of Azov, there are several more areas on which other Iranian languages, not taken for analysis, could have formed. Perhaps one of them, closer to the ancestral home of the first group of Pamir peoples, was the ancestral home of the ancestors of modern Vakhans and Ishkashim people.

The placing of the area of the Balochi language in the neighborhood to Vepsian area, based on scant available data about its connections with other Iranian languages, is supported by the presence of common words in the Vepsian and Balochi languages. For example, the Veps word naine “a daughter-in-law” corresponds Bal na'ānē “a daughter" at janaine “a woman". The same woman for the Balochi parents was the daughter and the daughter-in-law of her husband's family. Thus, not only lexical parallels but such evidence of a marriage between the Veps and Balochis confirms their neighborhood. Maybe Bel pērok "a grandfather" corresponds Veps per’eh "family". К. Häkkinen thinks that Fin. paksu, Est. and Veps. paks "thick" were borrowed from Iranian languages but refers only Bel. baz "thick, dense" (HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007: 860). Of the other Iranian, a similar word is found only in Ossetian – bæz "fat, thick". The ancestors of the Ossetians and Balochi were neighbors in the ancestral homeland. Lexical material from the Balochi language is scanty, but the Veps vocabulary was analyzed in comparison with the other Iranian languages. It turned out, that Kurdish had the biggest number of mutual words with Veps – 76, the runner-ups are Ossetic – 65 mutual words, Talyshi – 61 words, Gilaki – 56, Pashto – 45etc. You can see on the map that areas of the Kurdish and Ossetian languages are closest to the area of the Veps language and linguistic contacts between the populations of these areas also had to be close.

In general, there are several dozen words common to Kurdish, Vepsian, and three or more Iranian languages. Here are examples of Kurdish-Vepsian lexical parallels, for some of which there are also matches in other Iranian or Baltic-Finnish languages::

Kurd çeqandin “to stick, thrust in” – Veps. čokaita “the same”,

Kurd çerk “drop” – Veps. čirkštada “to drop”,

Kurd. cirnî “trough” – Veps. kurn “gutter”.

Kurd. e'ys "joy" – Veps. ijastus "joy".

Kurd. e'zim "beautiful" – Veps. izo "dear, sweet", Fin. ihana "wonderful, beautiful";

Kurd. hebhebok “spider”– Veps. hämähouk, Fin., Karel. hämähäkki – “spider”,

Kurd. henase “breathing” – Veps. henktä, Fin. hengittää, Est. hingake “to breathe”,

Kurd. hîrîn “neighing” – Veps. hirnaita, Fin. hirnua, Est. hirnuna “to neigh”,

Kurd. kusm “fear” – Veps. h’ämastoitta “to fear”,

Kurd. miraz “fear”, Tal. myrod, – Veps. mairiš “need”,

Kurd. semer “darkness”, xumar "gloomy", xumari "dark", xumri "red" – Veps. hämär “twilight” – Veps. hämär “twilight”, Fin. hämärä "twilight, dusky".

Kurd. xerez “speed, liveliness” – Veps. hered “fast, swift”, Erz. eriazi “agile, quick” .

The correspondences given here are different, and chance coincidences are not excluded, so each of them can be the topic of a separate study. The penultimate parallel is a particularly difficult case. M. Vasmer drew attention to the correspondence of the Finnish hämärä "dark" to Ukrainian. khmara "cloud" but did not see a possible connection between these words "for geographical reasons" (VASMER MAX. 1987, V. 4: 249). According to the phonology of the Baltic-Finnish languages, the original word should have been semer, and this may indicate the borrowing of Finnish words from Kurdish. In the etymological dictionary of the modern Finnish language, on the contrary, it is stated that the source of borrowing is an Old Germanic word, supposedly represented by Icelandic sámur "dark, dirty" (HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007: 238). However, in the authoritative dictionary of Old Norse, the word sámr is considered to be borrowed from the Finnish language (CLEASBY RICHARD, VIGFUSSON GUDBRANd. 1874). Kurdish semer can be associated with Kurd. samā "shadow", which is considered borrowed from Arabic sama "sky", "roof", "shadow" (TSABOLOV R.L. 2001. V. 2: 231), and Kurdish xumar also means "hangover" and is associated with Ar. xumār "painful condition after drinking", "hangover" (ibid: 484). Meanwhile, in the Chuvash language, there is the word khamăr "brown", "black", which semantically is much closer to the Kurdish and Baltic-Finnish words. Ukrainian khmara could be borrowed from Bulgar or Kurd. xumar as modified semer influenced by the Finnish languages.

The correspondence between Fin., Karel. hämähäkki, Veps hämähouk, Est. ämblik, Votes hämö, Livonian ämriki "spider" – Kurd. hebhebok "spider". Borrowing from Kurdish or another Iranian language into Vepsian is excluded because this word is isolated in Kurdish and associated with Ar. hebbāk "weaver" (ibid, 449). Finnish linguists did not notice this connection and consider the origin of the Baltic-Finnish words in secnce "dark" (HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007: 237). Based on phonology, the word for the name of the spider was formed from two roots ham and bōk of an unknown language, which could be Slavic or Germanic. Given the semantics and phonetics, Slav. pauk can be brought in for consideration, which can be connected with Germ. Bauch "belly" (North Gmc. būk). Slav. puzo "belly" may also have the same origin. (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 64). The abdomen is clearly expressed in the morphology of the spider's body, so its name could reflect this feature, and a definition was given to the meaning of "belly". A suitable word exists in Middle High German hem "evil, crafty", then the name of the spider can be understood as "evil belly". There is no such word in German, but it could exist in one of the extinct Germanic languages, for example, in Gothic. There is no explanation for how this word got to the Arabs. Considering that R. Tsabolov finds an Arabic correspondence for some of the other Iranian-Finnish correspondences given here, one might think that there is a big enigma behind all this. The answer to this enigma can be the history of the migration of the Kurdish people.(see the section Cimmerians)

The areas of the Kurdish and Talishi languages border the area of the Mordovian language. Accordingly, of all Iranian languages, except for Ossetian, Talysh, and Kurdish have the greatest number of words in common with the languages Moksha and Erzya – 62 each. There are 67 such words in the Ossetian language, but some of them come from later language contacts between Mordovians and the ancestors of Ossetians in the Scythian time. It should be noted on occasion that the numerical data presented here on the connections of individual pairs of languages do not exhaust their real number and are used only before comparison with each other, being taken from the same representative sample of sememes. With an increase in the sample size, we will receive new data, which should maintain their ratio. Examples of separate connections between Talysh and the Moksha and Erzya languages are given below:

Talishi-Mordvinic matches:

Tal. arə "to like" – Mok. yor-ams "to want";

Tal. kandul "hollow" – Erz. kundo "hollow";

Tal. kandy "bee" – Mok. kendi "wasp";

Tal. kәvәlә "snipe" – Mok. kaval "kite";

Tal. küm "roof" – Mok. kaval "cover";

Tal. latə "wedge" – Erz. lacho "wedge";

Tal. mejl "to want" - Mok. m'al' "wish";

Tal. se "to take" – Mok s'avoms, Erz/ saems "to take";

Tal. tiši "sprout" - Mok. tishe "grass";

Tal. tyk. "finish" – Mok. t'uk "finish"

Tal. vədə "a child" – Mok. eyde "a child".

Tal. vəšy "hunger" – Mok. vacha, Erz. vacho "hungry";

Kurdish-Mordvinic matches:

Kurd leyi "stream" – Mok. l'ay, Erz. ley "river",

Kurd çêl "cow" – Mok. skal "heifer", Erz. skal "cow",

Kurd sutin "to rub" – Mok. s'uder'-ams "to smouth, stroke",

Kurd ceh "barley" – Mok. chuzh, Erz. shuzh "barley".

The Pashto area was located near the Thracian one, which resulted in Pashto-Albanian lexical matches:

Pashto bus “chaff” – Alb byk “id”;

Pashto gаh “time” – Alb kohе “id”;

Pashto lêg’êr “naked” – Alb lakurig “id”;

Pashto peca “a part” – Alb pjesе “id”;

Pashto tar.ê l “to bind” – Alb thur “id”;

Pashto xwar “a wound” – Alb varrё “id”;

Pashto cira “a saw” – Alb sharrё “id” (though both can be from Lat cěrra).

Also few (due to the small size of the dictionary) examples of the linguistic connections of the Thracians with other neighbors – the ancestors of Sogdians and Yagnobians – are found:

Alb. hingеllin "to neigh" – Yagn. hinj'irast "to neigh",

Alb. anё "bank, shore" – Yag. xani "the same",

Alb. kurriz "back" – Yag. gûrk "back".

The connections between the Ossetian and Tocharian languages indicate that when the Indo-Aryans left their ancestral homeland and moved to Asia, the Tocharians remained in place. When they left their ancestral home, the Balts occupied their area, expanding their territory to the Dnieper. At this time, the Baltic languages were divided into two dialects – Eastern and Western. On the territory of the old ancestral home of the Balts to the west of the Berezina, a western dialect was formed, from which the Prussian and Yatvyazh languages later developed, and in the area between the Dnieper and Berezina, the eastern Baltic dialect was formed, from which the Lithuanian, Latvian, Semigallian, and Kuronian languages developed. When the Tocharians left their ancestral home, their habitat was occupied by Baltic tribes, expanding their territory to the Dnieper. At this time, the Baltic language was divided into two dialects – the eastern and western ones. On the territory of the old ancestral home of the Balts west of the Berezina River, the western dialect was formed, which from the Prussian and Yatvingian (Sudovian) languages were developed later, and in the area between the Dnieper and Berezina, the eastern Baltic dialect was formed, from which Lithuanian, Latvian, Zemgalian, and Curonian languages were developed.

Habitats of the Iranian and Germanic tribes in II mill. BC..

Thus, the eastern Balts came into direct contact with the ancestors of the Ossetians. Of course, it has affected their language, and certain matches between the Ossetic and East-Baltic languages could be identified. Many of them V.I. Abaev gave in his historical-etymological dictionary of the Ossetic language, but referred them to the Scythian time (A. ABAYEV V.I, 1958-1989), which is also, in principle, possible for some part of them.

The stay of the Iranians in their initial habitats, determined by us using the graphic-analytical method, is to a certain extent confirmed by place names. Iranian toponymy in the territory of Ukraine and Russia is in principle quite numerous but left mainly by the ancestors of modern Kurds and Ossetians and this topic is considered separately. These data are plotted on Google Maps.

In time some part of the Iranian peoples moved in the direction of Central Asia along the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea and came to the territory of modern Iran at the beginning of the 1st mill BC. Cuneiform sources of that time let us know about two groups of Irano-Aryans: Medes and Persians but other Iranian peoples not identified by name had to be somewhere east of them. Other Iranian tribes stayed in the Pontic parts.

General picture of the Iranian migration in Minor and Central Asia

Iranian peoples stay at the area of their original home, is to some extent confirmed by place names. Iranian place names in Ukraine and Russia are, in principle, quite numerous, but mostly left by the ancestors of modern Kurds and Ossetians and are discussed separately. Here are only the results on Google My Maps.

About mirgaration of Iranian tribes in Asia see in the section Cimmerians

About mirgaration of of a portion of Iranians in Central Europe see in the section Cimbri