Anglo-Saxons at Sources of Russian Power

In the historiography of Eastern Europe there are two directions: Normanists and anti-Normanists. The fundamental difference between them lies in the question of the origins of the statehood of Kyivan Rus. Normanists believe the Varangians laid its foundations, while anti-Normanists believe it developed naturally locally. In their dispute, which is approaching its three-hundredth anniversary, two concepts appear the Varangians and the Rus, the relationship between which determines the essence of the dispute. The content of the concept of Varangians is considered definite and is identified with the Swedes if it is not used as a metaphor, but the content of the concept of Rus remains uncertain and both sides put forward their own hypotheses about it. In this presentation, the Rus are understood as a people of Germanic origin and are associated with modern Flemings (see Mysterious Ancient People of Rus), while the concept of Varangians is expanded to a collective meaning, that is, to the one defined at their first mention in the chronicle.

The title of this article is an extension of the title of a book published almost a hundred years ago by one of the Soviet historians which I heard about for the first time when the article was finished (PARKHOMENKO Vl.A. 1924). This counterpart seems surprising, but it is no coincidence. The origin of the Russian state has been of interest to historians for 250 years, and the well-known saying of M.N. Pokrovsky “History is a policy that has been overturned into the past” was well reflected in the “patriotic” study of this topic. Since there is no doubt that the Russian state originated in the bowels of Kievan Rus', the interest was connected precisely with the origin of this state formation, and the mystery of the rise of Moscow in it remained practically unattended. The long struggle against the Varangian origins of Rus' is already ending with the triumph of the "Normanists", but now the patriotic part of historians has the opportunity to accept the evidence of the Anglo-Saxon roots of Russian statehood with hostility. The fact is that there are facts that give us evidence wie es eigentlich gewesen war*, in what Leopold von Ranke saw as the task of history. First of all, this is ancient toponymy, which in general, if historians use it, is only where everything is clear without it. Where there are no other facts, conjectural decoding of geographical names is put at the base of far-fetched hypotheses. In our case, Anglo-Saxon toponymy was used to confirm the results obtained by a completely different method, but due to its large number an additional argument.

The abundance of place names of Anglo-Saxon origin on the territory of Russia is a big enigma since no obvious traces of the Anglo-Saxons in any of the regions have hitherto been attested by historical documents. However, the evidence of place names can be quite plausible, if we treat them without prejudice. This happens when they are composed of semantically related parts with good phonetic correspondence to Old English words. For example, in Russia, seven settlements have the name Bibirevo, which has no convincing decoding in Slavic, Finno-Ugric, or Turkic languages. In Old English, you can find two words that are close in meaning, the addition of which is well suited for toponymy – OE. by: "group of houses" in names of settlements (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 39) and by:re "barn", "hut", "cabin" (ibid: 40). In other cases, the decoding of play names can well correspond to natural conditions and/or historical information. Both are well answered by decoding the name of the village Dydyldino, as part of the urban settlement Vidnoye in the Leninsky district of the Moscow Region using OE dead "dead", ielde "people". The meaning of the name "dead people" is in good agreement with the existence of a place of burial of people from ancient times. Near the village, there are burial mounds of presumably Old Russian times. In the scribe books from 1627, there was a church in the name of Elijah the Prophet which decay was noted already at that time. According to legend, at the beginning of the XV century, a female monastery was founded here by the wife of Prince Dmitry Donskoy. At the church, there is the Dydyldin cemetery currently known in Moscow, about which the following information was found:

Even in the time of the monastery founder, the Cathedral Ascension Church became the last resting place for female persons from the reigning family. In the cathedral were the graves of the Grand Duchesses, the wives of Tsar Ivan the Terrible, beginning with Anastasia Romanovna and ending with Maria Fedorovna – the mother of Tsarevich Dmitry, who was killed in the town of Uglich. Here were the tombs of the queens, and the wives of the kings from the house of the Romanovs. The last burial is dated 1731. Then, niece of Peter the Great (daughter of the half-brother of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich) Praskovya Ivanovna was buried in it (Historical reference on the Official website of the administration of the urban settlement Vidnoye of the Leninsky municipal district)

The Anglo-Saxon origin of many place names in Eastern Europe is very transparent for people who speak English but are scattered over a large area therefore many remain outside the scope of attention. When put together, they give the impression: Berkovo, Burgovo, Wolfa, Goldino, Lindino, Fastov, Firstovo, Fishovo, and many others are less obvious. The highest density of Anglo-Saxon place names is observed on the territory of the former Vladimir-Suzdal principality and especially around Moscow (Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe). From days of yore these places were inhabited by Finno-Ugric tribes, and the Slavs advanced here only at the end of the first millennium AD, but a hundred years later there arose the Rostov-Suzdal principality, which quickly seized the lead from Kyiv. The role of this principality in the history of the state creation of Russia is estimated very highly:

The special history of the Rostov-Suzdal land occupies a very prominent place in the general history of Russia and is very important for understanding our historical life.

In the land of Rostov-Suzdal, the youngest of the three tribes of our people, the Great Russian tribe, was formed and strengthened, consolidating and rallying the Russian land and creating the powerful Russian state. (KORSAKOV D., 1872, 1)

However, Russian historians, in particular, V.O. Klyuchevsky do not see a clear answer to the question of what ground has grown the new Upper Volga Rus (KLUCHEVSKIY V.O. 1956: 272). If we agree that the Anglo-Saxons founded the most ancient cities of this region, we must think that they laid the foundations of statehood here. They united under their domination of disparate native tribes, during the heyday of the Vladimir-Suzdal principality, they should have been completely assimilated by the local population, obviously, more numerous.

The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons, defined by the the graphic-analytical method, was located in one of the ethno-producing areas of the Dnieper Basin, namely between the Teterev, Pripyat, and Sluch Rivers. During the disintegration of the Proto-Germanic language, the initial English and Saxon dialects began to form there. Other Germanic peoples had their dwelling sites nearby along the Pripyat River. And in the basin of the left tributaries of the Dnieper lived differently Iranian tribes. It was four thousand years ago.

At left: The territory of the Germanic languages in II BC.

From their ancestral home, the Anglo-Saxons spread in different directions along the banks of the Dnieper and to the west and east. According to toponymy, a part of the Anglo-Saxons, crossing the Dnieper, settled along the banks of its left tributaries Sozh and Desna, displacing the Iranians who lived there before.

These newcomers can be associated with the emergence of the Sosnitsky variant of Trzciniec culture, common to all Germanic tribes. At about the same time, the neighboring Upper Volga region was inhabited by tribes of the Reticulated Ware culture developed on Gorodets and Diakovo cultures from the VII century BC till the V century AD. Their creators were considered to be the Finno-Ugric tribes of Ves', Merya, Muroma, Meshchera, and Mordvins (AVDUSIN D.A. 1977: 152-153).

From the area of the Sosnitsia culture, the Anglo-Saxons advanced southeastward and, approximately along the current Kharkiv-Rostov highway, entered the territory of the Donbas. There were rich deposits of copper ore in the vicinity of the city of Stakhanov developed since the Bronze Age. Taking control of the mining and processing of copper, the Anglo-Saxons achieved economic superiority and, accordingly, political dominance in the Northern Azov Sea. They headed a tribal alliance, known in history under the name Alans (in details see Alans – Angles – Saxons).

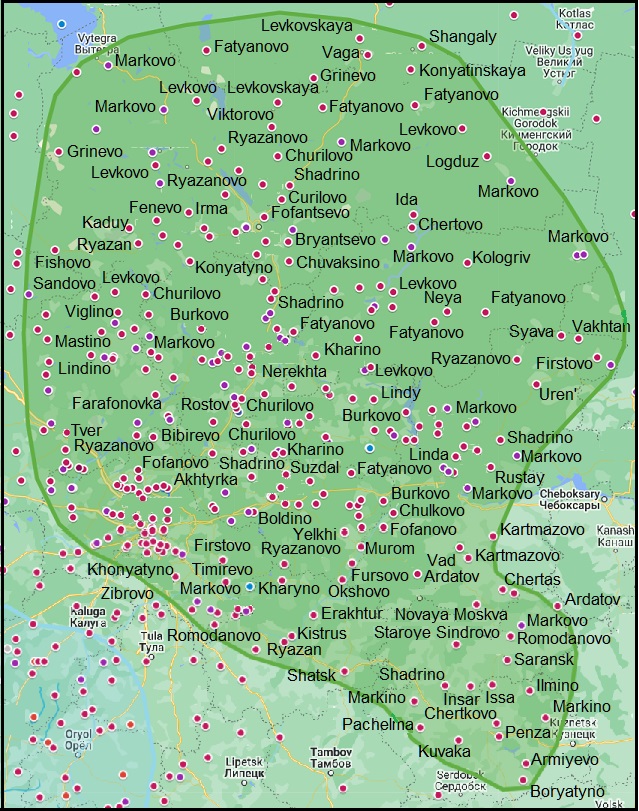

During the Great Migration of Nations, the Anglo-Saxons, fleeing the Hun invasion, migrated in search of free land for settlement. Some of them left together with other Germanic tribes for Western Europe, while the other part migrated towards the Upper Volga region, as evidenced by the place names of Central Russia, deciphered by the Old English language. Fleeing from the Huns, the Anglo-Saxons moved along the Oka River and looked for free places to settle. In suitable locations, they built fortified points, which grew into large cities of their time, such as Ryazan and Murom. During long stays, the nearest terrain was recognized. Thus, half-open spaces were discovered in the Moscow Region and in Zalesye ("behind the forest"), suitable for agriculture. The Anglo-Saxons, who have long since mastered farming in their former habitats in the Forest-Steppe, have found the habitual landscape and settled these regions, establishing xenocracy over the local Finnish population. Place names of the alleged Anglo-Saxon origin throughout Russia were found more than a hundred and fifty. Some of them may be random coincidences but in some cases, this probability can be negligible if the interpretation is confirmed by the features of the terrain or the semantic connection between the constituent parts of the name. In addition, the concentration of place names in a certain territory or their location in the form of a chain can say that at least some of them are decoded correctly. Among the most common names are: Markovo (97 settlements), Levkovo (25), Churilovo (24), Ryazanovo (22), Fatyanovo (18), Boldino (11), Burkovo (10). Their exact location is on the map Google, here only alleged decoding of the names are given.

Markovo – it seems to be the most common place-name of Russia. You can add to it Markino and the derivatives from them. One might think that they all occurred on behalf of a person, but such a name was not so popular in Russia for the corresponding anthroponyms far surpassed others in number. For example, the anthroponym Matveyevo was found only 20 times, and from the most common name Ivan – only 60. Of course, some of the place names originate on behalf of Mark, but a little, the bulk of them can be compared with OE. mearc, mearca "border", "sign", "mark", "county", "designated space". Such meanings of words are well suited to the names of settlements and are phonetically flawless. It is significant that these place names fill the missing links in their chains and are generally distributed among other Anglo-Saxon ones.

Levkovo, Levkivka, Levkiv a.o. – OE. lēf «weak», cofa «hut, cabin».

Churilovo – there was nothing found for reliable interpretation of the toponym in Russian, allegedly originating out of the name Churilo, which has no explanation. The high prevalence of the place name suggests that it should be based on a commonly used word and such is proposed by OE.ceorl "a man, peasant, husband", which corresponds with Eng. churl. Phonetic correspondence of Russian and English words is good (alternating k – č). We find the same alternation in the names of Chertanovo, Chertkovo, originating from the OE ceart "a wasteland, uncultivated public land" (on the contrary, the names of Kartmazovo, Kartino, etc. of the same origin kept k). Frequent use of the name of Churilovo and its derivatives may indicate that it was common for names of rural dwelling sites assigned them by earls.

Shadrino – some names may occur from the dial. shadra “smallpox”, but their prevalence raises doubts about this interpretation for the overwhelming majority of cases. Usually, names with negative meanings are rare. M. Vasmer does not consider the origin of this word, therefore it can be assumed that it originates from an OE sceard "maimed, chipped" taking into account the metathesis of consonants. Another meaning of this word is "plundered". Such a name could be given to the dwelling sites of the local population ravaged by the Anglo-Saxons. You can also consider OE sceader from scead "shadow, protection".

Ryazanovo – the name can be used partially by migrants from the Ryazan Region, and the name Ryazan itself may have a Slavic origin, although there is no complete certainty about it. You can keep in mind the OE rāsian "to explore, investigate", which could be used during relocating people when one has to find a suitable place to stay.

Fatyanovo – OE. fatian «to get».

Boldino – OE bold "house, home" suite by meaning and phonetically. The individual estates of landowners could be called so.

Burkovo – OE burg "borough".

Below is the Google My Maps with the marked assumed Anglo-Saxon place names in Central Russia and the most convincing explanations of some of them are given:

Google with the marked assumed Anglo-Saxon place names in Central Russia and the most convincing explanations of some of them are given:

Anglo-Saxon place names in Eastern Europe

On the map, most settlements of Anglo-Saxon origin are marked with dark-red points. The settlements of Markovo, Markino, and similar have purple color.

The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons is colored red, blue is the territory of the Sosnica culture, the green is the territory of the Rostov-Suzdal principality.

Berkino, villages in Moscow and Ivanovo Regions, the village of Berkovo in Vladimir Region – OE berc «birch».

Bryansk (Bryn' in chronicle), an administrative center of a region – OE. bryne „fire”.

Farafonovoо, villages in Oryol and Novgorod Regions, in Udmurtia, a village Farafonovka in Tver Region – OE faran «drive, go», faru “journey”, fōn «take, begin, do something».

Firstovo, two villages in Nizhniy Novgorod Region and a village in Moscoq Region – OE fyrst «first».

Fundrikovo, a village in Nizhniy Novgorod Region – OE. fundian «strive for, wish», ric «domination, government, power».

Fursovo, seven villages in Kaluga, Ryazan, Tula, and Kirov Regions – OE fyrs «furze, gorse, bramble» (the plant Genísta).

Kotlas, a town, Arkhangelsk Region – OE cot "hut, cabin", læs "pasture".

Linda, a village in town district of Nizhniy Novgorod Region, Linda, a village in Ivanovo Region, two villages Lindovo in Tver Region – OE lind «linden».

Moscow (Moskovъ or Moskovь in chronicle), the capital of Russia, villages Moskva in Tver, Pskov, and Kirov Regions, the Moskva River, lt Tisza – OE mos «bog, swamp», cofa «hut, cabin».

Murom, a town in Vladimir Region – OE mūr «wall», ōm «rust».

Nero, a lake in Yaroslav Region which banks on the city Rostov lies – OE neru "rescue", "food".

Penza – originally the name of the city being similar to Lat. penso, -āre “to weigh”, “to evaluate”, “to pay” was given by the Italics who migrated to the east (see Ancient Greeks and Italics in Ukraine and Russia), the Anglo-Saxons slightly changed its sound following OE pæneg "coin, money". Cf. Hung. pénz "money".

Romodanovo, a city in Mordovia, a village in the Glinka district of Smolensk Region, villages in Starozhilovsky and Rybnovsky districts of the Ryazan Region – OE. rūma „space”, dān „humid”.

Rostov, two cities in Russia, but there is another village of Rostov in the Sumy region, Ukraine – OE rūst "red", "rust". Possibly Slavic origin, but cf. Murom (see)

Ryazan, a city, 22 villages of Ryazanovo in different regions of Russia – OE. rāsian "explore, investigate". 2. ræsan "overthrow".

Suzdal, a city in Vladimir Region – OE. swæs «nice, pleasant, loved», dale «valley».

Tver (in the chronicles of Tkhver, Tfer, and others similar) – OE. đwǣre “obedient, pleasant, happy.”

Shenkursk, a town in Atkhangelsk REgion – д.-анг. scencan «to pour, give to drink, present», ūr «richness, wealth».

Wolfa, a river, lt of the Seym River, lt of the Desna – OE. wulf wolf.

Worgol, a village in Izmalkovo district of Lipetsk Region – OE. orgol "proud", "arrogant".

Wytebet', a river, lt of the Zhixdra River, rt of the Oka – OE. wid(e) «wide», bedd «riverbed».

Yurlovo, three villages in Moscow Region and one in Pskov Region – OE. eorl «noble man, warrior».

Ziborovo, a village in Zolotukhino district of Kursk Region, Ziborovka, a village in Shebekino district of Belgorod Region, villages Zibrovo in Tula, Oryol, Moscow Regions – OE. sibb «place», rōw "quiet".

A lot of supposed Anglo-Saxon settlements are located near Moscow. In some places, the distance between neighboring settlements is only 5-10 km. In general, density is such that it eliminates the possibility of placing all the names on the map above. For this purpose, the larger scale map was used (see below).

Some names have given decoding above, for others the following are proposed:

Akhtyrka – OE. eaht «advice, council, consideration», rice «government, authority, kingdom».

Darna – OS. darno, OE. darnunga «secret, covert».

Dedenevo – OE. dead «dead», eanian «to lamb, yean».

Chertanovo – OE. ceart «a wasteland, wild common land».

Fofanovo – OE fā «colorful, motley, potted, dyed», fana «cloth».

Kartino – OE. ceart «a wasteland, wild common land».

Kartmazovo – OE. ceart «a wasteland, wild common land», māg "bad".

Kitaygorod – д.-анг. ciete «hut, cabin".

Kuntsevo – OE cynca «cluster, bunch».

Ladoga – OE. lāđ «dangerous, hated, spiteful», -gē «region, locality».

Lytkarino – OE. lyt «little», carr «stone, rock».

Mamyri – OE. mamor(a) «deep sleep».

Miusy, a historical district in Moscow – OE. mēos «swamp, bog».

Oboldino – see Boldino.

Penyagino – OE. pæneg «coin, money».

Reutov – OE. reotan «cry, complain».

Sin'kovo – OE. sinc «treasure, riches».

White Rast – OE. ræst «quiet, calm».

These place names can be added by the names of the Neglinnaya and Yauza Rivers in Moscow. OE. nægl "nail, peg" suits well for the first river. The derivative of nægling (the name of the sword) is also fixed, but the motivation for such a name of the river remains unclear. The name for the second river can be found in the annals in the form of Auza, so OE. eage "eye, hole" (Ic. auga) is also well suited for deciphering, but the motivation remains not entirely clear, especially since the right tributaries of the Lama and Gzhat Rivers have the same name.

One could assume that the place name of supposed Anglo-Saxon origin belonged to the northern Germans, who already acted on the territory of Russia in historical times, as Varangians, by which the Swedes are meant. Indeed, many place names can be deciphered using the Old Icelandic language, which is considered to be "the classical language of the Scandinavian race" (An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Preface), this fact deceives scientists who hastened to conclude, "that toponymic data are an exposure to Scandinavian colonization in the territory of Ancient Rus» (RYDZEVSKAYA E. A. 1978, 136). According to the author of these words, such a conclusion is erroneous: "None of the ancient Russian urban centers bears a name that would be explained accordingly; none of them were founded by Scandinavian aliens" (ibid). Meanwhile, the names of such famous historical centers as Moscow, Ryazan, Suzdal, Murom can be explained with the help of the Old English language. In addition, there are many supposedly Germaniс place names, which cannot be deciphered with the help of Old Icelandic. On the other hand, the phonetic correspondence of Russian names with Old English words is often better than with Old Icelandic in cases where there is a difference between them. For example, OE. ceorl suits better than Ic. karl to decipher the name of Churilovo, since the derivative of the latter should have the form of Karlovo. In addition, the analysis of historical documents shows that the Varangians did not create their dwelling sites:

There is not the slightest indication of the occupation of unsettled territories by overseas visitors, the clearing and processing of untouched lands, the development of their natural resources, etc. As for the areas inhabited, they were also interested here in another: at first robbery and tribute, and in the future those trade relations that connected them with local shopping centers. The goal not less important and attractive for their wage service in Russia was not the acquisition of landholdings, but wages and pillage (the vassalage without fief relations – according to K. Marx). Undoubtedly, they not only often visited our country in the IX-XII centuries but also settled there in some cases; so, for example, it was in Ladoga, in Novgorod, in Kyiv, in Smolensk Gnezdov (RYDZEVSKAYA E.A. 1978: 135).

On the contrary, judging by the place names, the Anglo-Saxons were interested in mastering the new-found country (compare the meanings of the names used, such as the wasteland, the terrain-space, the searches, the first, farmer-farmer, house, hut, fish). Also, other data say that the question of the Scandinavian colonization of Rus' should be considered finally decidedly negative:

Such Scandinavian colonization as in England and Iceland was nowhere in Russia. In addition, the Swedes had no reason for mass emigration to the opposite shore of the Baltic Sea. There were rich and fertile areas In their own country (SAWYER PETER. 2002: 241-242)

On the other hand, population genetics data allow us to conclude that at some time Germanic tribes were present on the territory of Russia:

It turned out that the Norwegians and Germans are genetically closest to the Russian North; the Austrians, Swiss, Poles, Bosnians, Irish, and Scots were also included in the cluster. (BALANOVSKAYA E.V., PEZHEMCKIY D.V., ROMANOV A.G. a.o. 2011: 27).

According to the Genographic Project, the Russians are genetically close to the inhabitants of England, Denmark, and Germany (BELAKOV SERGEY, 2016: 407).

With all this in mind, the Anglo-Saxon toponymy, particularly in the interfluve of the Volga and the Oka rivers, can be correlated with the assumption of archaeologists about the penetration of a group of migrants of unknown ethnicity here, which resulted in the end of the development of Diakovo culture in the VII century. AD (SEDOV V.V., 2002: 390). Archaeological research has shown no continuity between local antiquities and the culture of the second half of the 1st millennium. The facts testify to the formation of a completely new culture in these places:

The migration process led to a radical restructuring of the resettlement system. The former small dwelling sites, confined to floodplain meadows, are mostly abandoned. Settlements of larger sizes, which had already gravitated to areas with the most fertile soils, were gaining spread. The leading role in the economy of the population is now played by agriculture. Moreover, the materials of archeology give grounds to talk about the development of arable farming with the possible specialization of individual dwelling sites on livestock, hunting, and fishing. Significantly, the population increases (SEDOV V.V. 2002: 390).

The stay of the Anglo-Saxons in the vicinity of the Finno-Ugres was to have a consequence of lexical correspondences between the Old English and Finno-Ugric languages. For example, Mari pundo "money" can be correlated with OE. pund "a pound, a measure of weight and a monetary unit." This word could reach the Mari through the Mordva, whose languages have pandoms "to pay", pandoma "fee", borrowed from the Anglo-Saxons. Other Germanic languages have similar words. It is believed that this is an early borrowing from Latin, which has pondō "pound" and pondus 'weight" (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 542). The Mari word is closer to the Latin and Old English, and not to the Mordovian words, so borrowing could only come from the Anglo-Saxons or the Italics. The presence of the Italcs and Greeks in Central Russia is considered separately, where Mari-Latin parallels are presented: Mari pundash "bottom" – Lat. fundus "bottom, foundation", Mari tuto "full" – Lat. totus "the whole" a.o. Below is a list of Mari words that could have been borrowed from Old English, where other words of the Italic substratum are also present:

Mari ar "conscience" – OE. ār "honor, dignity, glory, respect, mercy, happiness";

Mari archa "casket" (Chuv. archa "chest") – OE. earc(e) "ark, box" (лат. arca);

Mari, Moksha asu "utility" – under the condition of metathesis, one can consider OE. use "use, utility, custom" (Lat. usus "utility, custom");

Mari ȁngur "fishing rod" – OE. angel "fishing rod, hook, fishing hook";

Mari ȁngysyr "narrow" – OE. enge "narrow, tight";

Mari moštaš «be able to», Mok. maštoms "be able to, to own", Veps. mahtta "be able to", Fin. mahtaa "be able to" – OE. moste, past tense of mōtan «have to, be able to»;

Mari sala "whip' – OE. sȁl "rope, hobble, bridle";

Mari vadar "udder" (Fin., Est., Veps. udar "the same") – this borrowing could be only a rather late one from OE. udder "udder", but not, say, from the ancient Indian udhar, since initially, Finno-Ugric languages had no sound d, and similar words in the North Germanic languages are phonetically far away;

Mari var "feral, wild" – OE. bar "wild boar";

Traces of Anglo-Saxons can also be found in the dialect vocabulary of the Russian language, especially in areas of their mass settlement, for example, on the territory of the Vladimir-Suzdal principality. One of these traces can be the expression Elman language "an ancient Galician language", that is, the language of residents of the city of Galich (Kostroma Region). It is assumed that this word comes from close to Mari iylma "tongue as the organ in the mouth" (TKACHENKO O.B. 2007: 99). A tautology makes us search for the origins of a word in OE. el "alien, strange" and mann "man".

However, if we even agree with the presence of Anglo-Saxons in the space of the Rostov-Suzdal principality and especially around Moscow, this still does not say anything about the reason for the later successes of the principality and especially the future capital of Russia. We have already assumed the cause of the political elevation of the Anglo-Saxons among the tribal alliance in economic superiority. The same reason must be sought in this case. Events in Central Russia in the period after the appearance of the Anglo-Saxons had a great impact on Western Europe due to the activity of the Vikings, who ensured the flow of huge capital to Scandinavia in the form of silver, the size of which can be judged by the content of hoard finds along the routes of their trade and plundering campaigns.

Silver is the most significant feature in the famous hoards of the Vikings, and silver with the tools of measurement can be found in the trading centers of Scandinavia. It played an important role in the exchange practices of the Vikings and the economic and political development of Scandinavia (MERKEL STEPHEN WILLIAM. 2016, 35).

Vikings in Europe were the seafarers and marching groups of northern Germans who, depending on the circumstances, were engaged in trade and/or robbery outside their homeland. In Eastern Europe, they were called Varangians. As it turned out, their number also included Flemish merchants, who were the real Rus. The cooperation of this Rus with local authorities largely determined the political events of that time in Eastern Europe. Ibn Fadlan, who visited Volga Bulgaria as the secretary of the Caliph's colony, describes the Rus and their activities and does not mention any Varangians.

A significant part of the silver in the form of Kufic (Abbasid) dirhams began to enter Scandinavia from Bulgaria, often visited by Muslim merchants from the Arab Caliphate countries for exchange trade with the local population and the Ruses who arrived there, from the end of the VIII century after the economic rapprochement of Khazaria with the Arabs (KOMAR A.V. 2017: 61, 67). The ruling elite of the Arab Kaganate was the Anglo-Saxons (see Khazars.) and this simplified the formation of a trade route to the Muslim world along the Volga.

In exchange for the fur of sable, squirrel, ermine, ferret, weasel, marten, fox, beaver, goat and horse skins, wax, honey, fish glue, beaver stream, amber, and slave merchants offered luxuries and silver, the accumulation of which was a great passion for the Ruses. As far as the scale of the slave trade can be judged by the words of Ibn Fadlan, who pointed out that the Rus, arriving in Bulgaria, traditionally had to give one "head" from every dozen slaves to the local tsar. From this, it can be concluded that the total number of slaves brought with each Rusiian caravan consisted maybe of hundreds of ships.

Silver obtained in Bulgaria by robbery and trade was delivered by the Ruses to Sweden. The distribution point was Birka, located on the island of Björkö in Lake Mälaren near Stockholm (SAWYER PETER, 2002: 14). The delivery of silver from Bulgaria to Birka was carried out in different ways, some of which were preferred for various reasons. It is believed that all the trade went through Novgorod, but it acquired importance as a shopping center only in the tenth century (ibid). The insignificant role of Novgorod in trade with the East is evidenced by the small number and poverty of the treasures of Kufic dirhams found in the Novgorod region. It can be reasonably assumed that the Scandinavians used for trade a shorter, long-mastered route along the Western Dvina, along which they migrated to Scandinavia from their ancestral home at the end of the second millennium BC. (see the section North Germanic Place Names in Belarus, Baltic States, and Russia ). The poor treasures of Kufic dirhams in Novgorod speak only of the fact that here the Varangians could stock up on furs, wax, and honey, but they did not need to return there on their way back to Sweden. The finding of a treasure of Kufic coins weighing more than 40 kilograms in Murom indicates that the Varangians traveled along the Oka River, however, it was easier to get to Novgorod by sailing along the Volga and further along the Tver River to the rivers of the Baltic basin. From the Oka, merchant vessels could go up the Moscow River and through the Ruza, Vazuza, and Dnieper Rivers to get to the Western Dvina. This way is not easy, because several times they would have to pull ships from the river to the river by dragging. The trek lasted several months and from time to time it was necessary to make stops to provide food taken from the local population, which required certain expenses.

However, the Great Volga Route stands out among all the main thoroughfares, connecting Europe with Asia. It is evaluated as "outstanding geopolitical, cultural, transport and trade, international and interstate importance." Export-import operations on it brought fabulous profits to merchants, reaching 1000 %. (KIRPICHNIKOV A.N. 2006, 34). Particularly profitable was the trade with slaves.

The slave trade is connected with logistical difficulties, so the acquisition of them by Scandinavian merchants should have taken place in the area nearest to Bulgaria. The towns of Rostov and Suzdal, the future centers of the principality didn't lie on the main trade routes, so the slave trade was only the base of their subsequent raising. Local princes supplied slaves for the Varangians to the ports on the Oka and Volga at the time of flourishing trade with the countries of the Caliphate. The local princes, in exchange for silver dirhams, supplied the Varangians with slaves to the ports on the Oka and Volga during the heyday of trade with the countries of the Caliphate. Trade with Abbasid Tabaristan on the southern coast of the Caspian Sea and Samanid Central Asia proceeded in two directions:

during the first eighty years of the IX cen. Islamic silver entered Eastern Europe from the Middle East through the Caucasus / Caspian Sea and Khazaria, between about 900 and the beginning of the XI cen., it was delivered there mainly from Samanid Central Asia through South Ural steppes and Volga Bulgaria. This flow of Central Asian dirhams ceased in the second decade of the XI cen. (KOVALEV R.K. 2015: 96-97).

Silver trade routes were reconstructed from the scale of dirham hoards.

(MERKEL STEPHEN WILLIAM. 2016: 63. Fig. 4-7).

The path of the Abbasid dirhams through the Caspian Sea and Khazaria from Iraq and Iran is marked in yellow, the path of the Samanid dirhams from Central Asia is red, and the conditional path from Bulgaria to Sweden is orange.

The dense concentration of Anglo-Saxon place names around Moscow was a reason for favorable geographical conditions, which caused intensive settlement of this region. During Prince Yuri Dolgoruky (the XII century), Moscow was already a rich village. Diversity of the local landscape predetermines economic success for the local population:

At first, the Moscow area represented many rural amenities for the founding of broad agriculture. The so-called Great Meadow of Zamoskvorechye, lying against the Kremlin mountain, delivered a vast pasture for cattle and especially for prince's horse herds. The surrounding meadows and fields with rivers and streams crossing them served as glorious lands for farming, horticulture, and gardening, not to mention fattened hayfields. Unduobtly the field adjacent to the Kremlin Mountain Kuchkovo was covered with arable land (ZABELIN IVAN. 1905: 4).

The developed cattle breeding, obviously, and beekeeping were a good source of enrichment for Muscovites – horse and goatskins, honey, and wax were in great demand in the East. The Varangians enjoyed the goods here with pleasure, leaving for the local entrepreneurs a considerable part of the silver coins that were earned when selling luxury goods in Birka. Thus, large capital was accumulated in Moscow, which ensured political success for the local elite in the future.

The existence of an older settlement on the site of ancient Moscow is confirmed by repeated random discoveries of silver items and coins dating from the X century. And it is not by accident that the name of the former village of Penyagino, which now belongs to Moscow, lurks OE pæneg "coin, money". However, numerous dwelling sites of Moscow space of the VII-IX centuries remain poorly studied, and its history seems vague, especially in ethnogenetic processes (SEDOVV.V., 2002: 390). The Volga-Klyazma interfluve is more explored in archaeological terms, and archaeological finds indicate that the local population was mixed, main creators of the Merian culture spread here were not local Finns, but, according to V. Sedov, "Central European newcomers" (ibid: 393). Ethnic heterogeneity of the population forced the aliens, who were in the minority, to build fortified dwelling sites, an example of which may be the Sarskoye hillfort on the shore of Lake Nero. Its middle part, enclosed by ramparts, occupied an area of 8,000 square meters. (ibid, 391).

Lake Nero and Sarskoye hillfort.

The photo from the sine Historicsl notes

The map shows that there is a peninsula on Lake Nero, in connection with which it is appropriate to describe the land of the Rus' by the eastern scholar Ibn Rustah, dating back to the first third of the 10th century:

As for Russia, it is located on an island surrounded by a lake. The circumference of this lake, on which they (Rus') live, is equal to three day's journey; it is covered with forests and swamps; unhealthy and cheese to the point that it is worth stepping on the ground with your foot, and it is already shaking due to (looseness from) pouring water in it (CHWOLSON D.A. 1869: 34).

The Sarskoye hillfort differed significantly from the dwelling sites of the Finno-Ugric population. Archaeological finds attest to its two distinct functions, military and commercial, as illustrated by a large number of weapons along with Islamic coins and objects of foreign origin [HEDENSTIERNA-JONSON CHARLOTTA. 2009: 161].

Most likely the peninsula on the lake, like the Sarskoye hillfort, was their stronghold for the Anglo-Saxons. The sense "rusty" of the names of Rostov and another fortress Murom (OE rūst "rust", mūr "wall", ōm "rust") seems to be enigmatic. However, in Germanic, as well as in other languages, the words meaning rust go back to the same root as the words "red" (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 606), therefore, OE rūst could mean different shades of red.

Anglo-Saxon place names on the territory of the Vladimir-Suzdal Principality

Ibn Rusta speaks of the Rus and the Slavs, clearly as different peoples, and at the same time the Rus raid the Slavs to capture prisoners, who are then sold to the Khazars or Bulgars. They do not engage in arable farming and feed on what they get from the Slavs (CHWOLSON D.A. 1869: 35). Chwolson understands the Slavs as “Sakaliba” by Arabic, and Arab scholars often talk about the “Sakaliba” people, different from the Russians, but, as Ashmarin pointed out, this is what they generally called the entire blond population of northeastern Europe. Anglo-Saxons, who were close to the Rus in language, could be called the common name Rus by the local population.

Rostov and Murom were the administrative centers of the two dominant Anglo-Saxon tribes in the territories of the later Vladimir-Suzdal and Murom-Ryazan principalities. The elite of the tribes concentrated in their hands considerable capital earned from the trade of furs and slaves from among the indigenous population. By identifying the inhabitants of these cities with the Anglo-Saxons, one can assume their close cooperation with the Rus, who hold in hand all trade with the countries of the East. Since trade went through Khazaria, it had to be controlled by the Khazarian authorities, also consisted of Anglo-Saxons. Khazaria traded not only with the East but also with Constantinople, using the trade route along the Dnieper. The Ruses did not want to have intermediaries in trade, so they sought to establish direct trade relations with Constantinople. Impeding their development, the Khazars blocked a possible way to the Constantinople market by building the Sarkel fortress on the isthmus between the Don and the Volga. This led to a worsening of relations between the rivals, who became hostile after the insidious murder of the Khazarian proteges Askold and Dir in Kyiv. Their names indicate their national affiliation (cf. Dir – OE. dieren "to appreciate, praise", diere "dear, valuable, noble", Askold – OE. āscian "ask, demand", "call, elect" and eald, Eng. old), ealdor "prince, lord"). In the eyes of the Khazar Anglo-Saxons, the Rus became criminals following the Old Saxon word war(a)g “criminal” (Holthausen F. 1974, 386). In the interests of trade, the Rus always actively collaborated with local authorities and, trying to make their way into Constantinople, willingly accepted the Swedes into their ranks, for whom the prospect of trade relations with Constantinople was also attractive. Because they cooperated with the Rus, the sobriquet "Varyags" also extended to them.

The stubborn struggle for the market lasted about a hundred years and the Russians won. Having finally taken control of the route along the Dnieper after Prince Svyatoslav’s campaign against Khazaria in 965, Rus', already as a state, established close trade relations with Constantinople. Anglo-Saxon rule in Khazaria ended, but on the Volga, the Anglo-Saxons determined the local political system for a long time.

Almost all the names of tribes mentioned in the chronicle correspond with the names of modern peoples. The exception is the Merya tribe, of which there is no consensus, in general, it is considered to be a Volga-Finnish one, and some scholars identify the Merya with the Mari people. It is true, but it could be an ethnicon, the name of a population of a certain locality. The Slavs of the Volga-Klyazma interfluve are mentioned as "Merya" in the Tale of Bygone Years (TBY). The people under this name stood out, especially in the TBY, it was noticeably different from other Finno-Ugric tribes and was very influential, at least numerous. When enumerating the Finno-Ugric tribes in the TBY, the Merya always ranks second after the Chud'. Only Meria from all the Finno-Ugric peoples took part in the military campaigns of Prince Oleg. The Anglo-Saxons who inhabited the Meria area could also be called by this name and under this name take part in Oleg’s campaigns. At the same time, the Merya people had their language, in the knowledge of which, judging by historical documents, "a rather high value was seen, apparently due to its role in the Vladimir-Suzdal principality" (TKACHENKO O.B. 2007. 10)

However, "after the X-XI cen. the Merya ceases to be mentioned in the ancient Russian chronicles" (ibid: 10). The question arises – why such a tribe influential up to this time will cease to be mentioned in the annals. The fact that it could not so quickly assimilate among the Slavs, modern scholars cannot agree and therefore seek evidence that it nevertheless continued to exist on its lands, where the Eastern Slavs began to penetrate from X-XI. There is no reliable evidence for this, therefore, it is assumed that there is a certain process of “economic and ethnolinguistic consolidation” (ibid: 11). If this is so, then it will be necessary to admit that the people of Merya disappeared without a trace, while other Finno-Ugrians have retained their national identity to this day. Alex Tolochko in the foreword to his book "Sketches of Primary Russia" writes:

Anyone who begins to study a new historical topic is asked three questions: what reliable evidence has been preserved? What does science say about this? And: how everything was really? (TOLOCHKO ALEKSEY. 2015: 12)

For our study, reliable evidence is toponymy, while historical documents (mostly the Tale of Bygone Years) and materials from previous studies are used very prudently. I fully share the thought of Alex Tolochko that all attempts to expose the early history of Eastern Europe, for lack of other reliable sources, based upon the Tale of Bygone Years, which he treats critically, pointing to the obvious speculations of the chronicler in those cases when it refers to the affairs of yore. He tries analyzing the chronicle text to find reliable evidence for his hypothesis that the common name of Rus hides two related communities, even societies – the Scandinavian and Southern Rus. At the same time, he recklessly argues that "we will never know what origin was the word that gave rise to Russia" (ibid: 154).

Developing the idea of the two communities of Russia, Tolochko notes that it is possible to single out among the population of Eastern Europe "rustic Vikings" engaged in cultivating the land, and in connection with this he writes:

It should be remembered that rustical colonization and long-distance trade are two completely different phenomena in a seemingly uniform stream of Scandinavian advancement to Eastern Europe. Strikingly different occupations, ways of life, cultural experiences, social positions were to form, ultimately, and different identities (TOLOCHKO ALEKSEY. 2015; 168).

In what exactly places "rustic Vikings" left their traces, Tolochko does not specify. But with attention to his conclusion, we can consider them Anglo-Saxons. At least in the Moscow area, they showed themselves just so. Considering the “village Vikings” Scandinavians only by the swords found in rural contexts, what A. Tolochko believes characteristics of Scandinavia, is too little to talk about their true origin. Relations between the Anglo-Saxons and the surrounding population, among whom they acquired through violence "living goods" for the practiced slave trade, could not be peaceful. In this regard, the villagers were supposed to have weapons just in case, and in such conditions, a military feudal estate had to form among the Anglo-Saxons, but without a legitimate single ruler. Vague memories of local nobles are contained in the legends of the boyar Stephan Kuchka (cf. with the name Kutsi obove), who owned Moscow before Yuri Dolgoruky. Historical information about Kuchka is not preserved, however, numerous place names in the outskirts of Moscow containing his name speak of his role in the region’s history, and even Moscow itself was first called Kuchkovo. For disrespect for the prince, who entered the possessions of Kuchka, Yuri Dolgoruky ordered him to be put to death (KORSAKOV D., 1872, 78). Hiding evil for the princely family, over time his sons and son-in-law entered into a conversation with other boyars and killed Andrew Bogolyubsky, the son of Yury. M. Tikhomirov believed the great Kuchka family was a close-knit force in this region and left memories in folk legends until the nineteenth century (TIKHOMIROBV MIKHAIL. 2003, 35). This memory reflects the hostility of the independent local, so-called land boyars to the alien princely power of the Rurik dynasty from Kiev. Kuchka's name may be connected with OE cuc, cwic "lively, quick".

Formation of the influential nobility of the land boyars took a long time, so its roots must go deep in history. There are no legends about the founding of the town of Rostov, but by the time of Yuri Dolgoruky, it was already called great. This fact and the foundation of Rostov in the wilderness, away from waterways causes bewilderment (KORSAKOV D., 1872, 61-62, 79). In the period from 913 to 988, there is no mention of the Rostov land in the annals, but it can be assumed that the silver crisis that began in the second half of the 10th century put an end to the prosperity of Rostov and Suzdal. This crisis completed the period of the initial accumulation of capital which was concentrated in the hands of the land boyars which needed to find an application using local resources and the existing infrastructure. This opportunity appeared sometime after the entry of Rostov into the Kiev state.

The mutual relations of the Kiev princes and the Anglo-Saxons are to a certain extent reflected in the Russian epic of Churilo Plenkovich. About the Anglo-Saxon origin of the name Churilo mentioned above, the patronymic Plenkovich can also have Anglo-Saxon roots if we take into account OE flean "flay" and -ing is a verbal suffix meaning action or its result. The circumstances of the epic and its hero differ from the realities of other epics. Its essence is in the peculiarities of Churila’s service to the Kiev Prince Vladimir. There is an assumption that the plot of the epic is connected with the stay in Kiev of one of the leaders of the conquered tribes:

The victory of Kiev, winning over a hostile tribe, the capture of the leader of this tribe and his relocation to Kiev, the service of a noble captive in the house of the victorious prince – all this could be the subject of chants, inspire the creation of epics. Over the long years of existence of the song, measured by centuries, its primary basis has lost its clarity under the influence of innovations, becoming one of the components of a multi-layered epic structure (FROYANOV I.Ya. 2012: 33).

Analyzing the epic, I. Froyanov sees the relations of Vladimir and Churilo as "subject relations", in which the latter acts as a defeated party and his service is not voluntary but forced and relates only to the prince’s person:

Even though some epic records narrate about the service of the Churils to all of Kyiv, one must nevertheless say: that he serves Vladimir specifically as a private individual and householder, which makes him noticeably different from other heroes who usually serve Russia, the people of Russia, defending their native land from the enemy (ibid: 30).

From the second quarter and middle of the XI cen. with the development of the path "from the Varangians to the Greeks", close trade, cultural, and political ties between Kyiv and Byzantium begin, and first from south to north, because "the initiative in international trade relations always belongs to a more cultural and economically developed nation" (PARKHOMENKO Vl.A. 1924, 87). In such a way, Kyiv gained experience in state-building and the development of state traditions. The dynastic ruling of people "ready to convert economic dominance into political power" is being established there (TOLOCHKO ALEKSEY. 2015. 314). In this sense, the Upper Volga region was best prepared economically, but not politically. The difference in the level of development of the economy of Russia as a whole and its regions is characterized by the volume of money supply in circulation at that time. It can be judged by the composition and the number of random finds of treasures containing coins of different minting. The number of found coins of Russian (mainly Kiev) minting in the hoards of the X-XI centuries does not exceed 340 specimens (SOTNIKOVA M.P., SPASSKIY I.G. 1983: 112), there are only about 700 hoards with Kufic dirhams in European Russia and some finds can have several hundred and even thousands of coins. For example, in a treasure found near the city of Murom on the Oka River, two copper jugs contained 11 thousand dirhams from the 8th-10th centuries with a total weight of about 42 kg (VEKSLER A.G., MELNIKOVA A.S. 1973: 18). There were no such impressive finds near Moscow, but in the Zaraisk hoard found at the junction of the Moscow and Ryazan Regions, 283 Kufic (mainly Abbasid) dirhams were found (ibid: 20). Thus, the financial capabilities of the Kiev principality do not go into any alignment with the capabilities of the Vladimir principality, and this determined their future fate. The reasons that determined the formation of the core of statehood in Kyiv lay not so much in the commercial sphere as in the cultural sphere:

Kiev’s growth was not… associated with or dependent upon the Islamic trade. Although it did become involved in the Islamic trade and benefited from it during the first quarter of the tenth century, it was engaged even more intensively in commercial and cultural relations with Byzantium, which were defined by treaties concluded in 911 and again in 945. Rus’ ties with Byzantium extended beyond trade. The Rus’ leaders provided assistance for Byzantine emperors in selected military campaigns. Cultural ties were represented most importantly by the Rus’ adoption of Christianity…… (MARTIN JANET. 200: 167).

The campaigns of Prince Svyatoslav to Volga Bulgaria and Khazaria were the finale of the struggle for the Constantinople market. Weakened by internal contradictions, Khazaria fell and the flow of Kufic silver to the north dried up. The fact of almost complete absence of hoards of dirhams dating from the chronicle period of Svyatoslav’s campaigns (964–972) indicates that the prince’s adventure interrupted the normal functioning of trade routes along the Volga (SAWYER PETER. 2002, 292; PASHINSKIY VLADIMIR: 2019, 54-62). This largely determined the attitude of the Anglo-Saxons towards Kyiv for many years.

The absence of the Kyiv dynasty princes in the Upper Volga until the last years of the XI cen. gives reason to assume "that there should have been local princely dynasties here" (PARKHOMENKO Vl.A. 1924: 103). In the end, they could not resist the onset of Kyiv. Intending to establish domination in the newly acquired land, Yaroslav the Wise laid down the city of Yaroslavl on the Volga and Vladimir Monomakh founded the city of Vladimir on the Klyazma River as base points. Alien rejection by the land boyars led to the so-called "revolts of the volhves" in 1024 and 1071. Usually, the "volhv" means some priests or sorcerers the meaning of Old Rus. vŭlhv "magician". Similar words are present in the South Slavic languages, the ancestors of the speakers of which populated the areas of the left bank of the Dnieper River. In the Western Slavic languages formed on the Right Bank, such a word is absent, so it is not Common Slavic, but its etymology is controversial.

Wizards, magicians, and all sorts of soothsayers and healers were rare among ordinary people, while the volhves were supposed to be numerous. According to the chronicles during the uprising of 1024, the volhves killed many ordinary people, mostly women, but also men. A handful of rebels couldn’t do it, and it’s not an affair of magicians to raise revolts. I. Froyanov concludes that "the ethnicity of the participants in the events of 1024 does not lend itself to precise definition" (FROYANOV I.Ya. 2012:91). He did not know about the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Suzdal land, otherwise he would have concluded that the volhves were Anglo-Saxon nobility, called themselves "wolves" if we take into account OE. wulfs "wolves". According to Herodotus, a belief existed that the Neuroi, which we associate with the Anglo-Saxons, turned into wolves once a year. Therefore, they could get the name "volf", which the Slavs pronounced as "volhv". These Volhves worshiped their gods, among whom Veles was in the first place. His figure as the main deity was preserved in Rostov for a long time even after the adoption of Christianity. The name of Veles can be of Anglo-Saxon origin if following OE. wela "good, happiness". Ibn Rustah reports next about the significant role of religion in the life of the Rus, which we understand as the Anglo-Saxons:

Among them, they have doctors who have such an influence on their king, as if they were his chiefs. Sometimes they order them to sacrifice to their creator whatever they like: women, men, and horses; when the doctor orders, it is impossible not to obey his orders in any way (CHWOLSON D.A. 1869: 38).

It is not clear from the annals how these revolts ended, there were no big changes in the region until the activity was shown by Yuri Dolgoruky here, setting up cities among which were Pereslavl-Zalessky, Yuriev Polsky, Dmitrov and others. His affair was continued by Andrei Bogolyubsky, who strengthened his reign in 1155 after the seizure of power by his father in Kiev. The construction required money and there is no other explanation than that it was provided by the capital accumulated by the local nobility in the good old days. The richness of Christian architecture, preserved in the chronicler's description is especially impressive. The abundance of gold in the decoration of the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir struck contemporaries compelling them to compare the building with the temple of Solomon (PLUGIN V.A. 1989: 27). Clear, that the greedy Dolgoruky and his son obtained funds for the construction and decoration of temples through expropriating from the owners, they did not have other opportunities.

The importance of our topic is participating in the construction of the Assumption Cathedral in the city of Vladimir an architect and the German masters who gave the cathedral the features of the Romanesque style that first appeared in Russia. According to V.N. Tatishchev, an architect has been sent with the embassy to Andrei Bogolyubsky by Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (ZAGRAEVSKIY S.V. 2013, 184-195). Some facts say that there was a close relationship between the emperor and the grand duke, expressed, in particular, in the exchange of expensive gifts. Frederick I also knew Andrei Bogolyubsky’s sister Olga; for some reason, he provided her with some help before setting out on the Third Crusade. Historians know these facts and they find roundabout explanations for the desire of the Vladimir princes to “fit into the developing system of Baltic contacts.” There is also an assumption that some relations between the emperor and the Grand Duke existed expressed in the exchange of gifts. Such a relationship is a great historical enigma, its solution may be that contacts with the emperor could be established due to the presence in the principality of the Anglo-Saxons. It is also possible that military experts could attend the German embassy, who helped organize an operation against Kyiv where Grand Prince Mstislav reigned at that time:

In 1169, 12 princes opposed Mstislav, which came from the seven ends of Russia – all Rostislavichi, Oleg and Igor Svyatoslavich, Gleb Yurievich, Vladimir Andreevich and others. According to the Nikon annals, the forces of the Russian princes were joined by "Cuman princes with the Cumans, and Ugrians, and Czechs, and Poles, and Lithuanians, and many many armies together moving to Kiev" (TOLOCHKO PETRO. 1996: 123).

After a long siege, Kiev was captured and plundered, which gave rise to its subsequent decline. Historians find no apparent reason for such an organized campaign to destroy the capital of the principality, which could not be hostile to absolutely all its close and distant neighbors. The joining of dissimilar forces can be explained only by the intention of Andrei Bogolyousky, who only had sufficient funds to organize and finance this great undertaking. The fall of Kiev Russian historian S.M. Soloviev called "an event of the greatest importance, a turning point event, from which history took a new course, from which a new order of things began in Russia" (SOLOVYEV S.M. 1960. Book II, chapter 6). Bogolyubsky did not reign in Kiev, but put his younger brother to reign, thus becoming the founder of a new state.

Additional labor was required for building new cities in Rostov-Suzdal land. They were attracted as free settlers and this contributed also to the development of agriculture and manufacturing. Tatishchev wrote that Yuri Dolgoruky gathered people from everywhere, but mainly from the south and provided them with a considerable loan and other assistance (KORSAKOV D. 1872: 76). No information from where he took the money was preserved in the annals, but his successors used the same sources.

So gradually the Grand Duchy of Vladimir was being built and gaining strength, at the heart of its success lay the entrepreneurial tradition and capital of the Anglo-Saxons settled here once, but forced to seek new happiness elsewhere over time. The activities of Andrei Bogolyubsky, who needed funds for further town planning and active foreign policy, caused a new dissatisfaction among the "wolves", including the Kuchkovich clan. Their struggle with the prince ended with his assassination in 1174. According to the report of the Institute of Archeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2015, during the restoration of the Transfiguration Cathedral in the city of Pereslavl-Zalessky, a list of 20 names of participants in the murder of the prince was found on the wall of the church. However, one can read only a few, like the Prince’s son-in-law Pyotr Kuchkov, his brothers Ambal and Yakim Kuchkoviches, and certain Ivka, Petko, and Styryata. Non-Christian names may be Anglo-Saxon. At least the last of them can be associated with the OE styria "sturgeon" or styrian "move, excite, drive."

Two years after the murder, most of the conspirators were executed and this did not foreshow a reconciliation between the Vladimir prince's power and the Anglo-Saxons, which continue to have great influence in the towns of Suzdal and Rostov. It can be assumed that fearing further harassment and not being able to withstand the hostile growing Vladimir, leaders of the Anglo-Saxons considered it best to flee with a great part of their tribesmen in Volga Bulgaria (see further Volga Bulgars). The remaining part quickly assimilated among the Slavs, however, the Anglo-Saxons left their traces in the dialect vocabulary of the Russian language in the areas of their mass settlement, including on the territory of the Vladimir-Suzdal principality. One of these traces may be the expression Elman language “ancient Galician language,” that is, the inhabitants of Galich (Kostroma region). The word is believed to be derived from something close to Mar. yylma “tongue as an organ of speech” (Tkachenko O.B. 2007, 99). Tautology forces us to look for the origins of the word in OE. el “stranger” and mann “person”. The word yols "goblin, devil" recorded in the Yaroslavl, Kostroma, and Ivanovo regions can be associated with OE. eolh "elk". The roar of an elk in the forest could frighten surrounding residents. These words were discovered by chance, but if you search purposefully in dialect dictionaries, many more ancient Anglicisms should be discovered.

The picture of the Anglo-Saxon colonization of the Upper Volga basin presented here is partly contradicted by the Timerevo archeological complex near Yaroslavl. However, its general description and significance for the development of statehood do not contradict this picture at all:

The concentration of the largest the IX century treasures of Arabic silver finds of household items, weapons, and jewelry of imported origin, a large area of the settlement, and the multi-ethnic composition of its population suggest that Timerevo was a key trade and craft and military administrative point on the Baltic-Volga route. The beginning of the functioning of Timerevo dates back to the third quarter of the IX century, as evidenced by the treasures, the first burials of the burial ground, and the early complexes of dwelling sites. Since the inclusion of the territory of the Yaroslavl Volga region into the ancient Russian state, Timerevo, taking into account the existing potential, could play the role of a stronghold of the princely local authority — "a pogost" and at the same time a stronghold for the further development of Finno-Ugric lands, which in large numbers began in the second half of the XI century while resetting peasants – the farmers, already with the help of the emerging feudal power (SEDYKH V.N. 2007: 5)

Our picture is contradicted by the close ties between Timerevo and Scandinavia and the leading role of Scandinavians in a military organization, which the author repeatedly underlines. It may be objected that items of the Scandinavian material culture could penetrate the Upper Volga via the trade route. As for the similarity between the device of Timerevo’s mounds and the Scandinavian ones, it can be noted that their possible connection with the Alanian Black Sea mounds was not checked. V.N. Sedykh also indicates that in addition to trade, craft, and military affairs, "the Timerevo population was engaged in agriculture, hunting, fishing, various crafts" (Ibid: 4). Such activities, as mentioned above, were not typical for the Vikings, and they had no reason to establish their dwelling sites, especially aside from the trade route. Also, the Vikings could not take women on their campaigns, and many female burials in the Timerevo burial grounds (NEFEDOV SREGEY. 2010: 98) contradict their Varangian affiliation.

Thus, there are no serious reasons for admitting founding the Timerevo by the Anglo-Saxons. The etymology of its name speaks in favor of this too – OE team "tribe, clan, family, gang" and ear "earth", i.e. "tribal land". In the dictionary of the Icelandic language, nothing suitable for the interpretation of the name was found. It is also worth noting that, far from the Volga trade route, there are three villages Timerevo in the Ivanovo, Vladimir, and Moscow Region.

The significance of the participation of the Anglo-Saxons in the creation of Russian statehood is enormous. It was they who, realizing the dependence of politics on capital, laid down the principle of state acquisitions, which accompanied the entire history of Russia and was described by S.M. Solovyov in these words:

Sometimes we see how entire generations in the course of many and many years accumulate great wealth through hard work: a son adds to what his father has accumulated, a grandson increases the amount collected by his father and grandfather; quietly, slowly, imperceptibly they act, are subjected to deprivations, live poorly; and finally, the accumulated funds reach an extensive size, and finally, the happy heir of the hardworking and thrifty ancestors begins to use the wealth he has inherited. He does not squander it, on the contrary, he is increasing it; but at the same time, the method of its actions, by the vastness of the funds itself, is already large, it becomes loud, visible, attracts everyone’s attention, because it influences destiny, on the welfare of many. Honor and glory to the man who so wisely knew how to use the means he got; but at the same time should the modest ancestors be forgotten, who by their labor, thrift, and deprivation delivered these funds to him? (SOLOVIEV S.M. 1960. Book III: 7)

Following the words of the Russian historian, Russia should thank the Anglo-Saxons, who stood at the origins of its statehood. Although the politically active elite of the Anglo-Saxons, accompanied by a large part of their fellow tribesmen, left for the Urals, no less of them, scattered throughout the principality, remained in place. The Anglo-Saxons, being on the periphery in a minority among the arriving mass of Slavs, headed the local administration and should not have conflicts with the princely authorities, so there was no point in changing anything in their position. Over time, they dissolved among the Russians but left a certain material and social capital, which became the basis for subsequent state building. One might also think that in those distant times, Russians learned from the Anglo-Saxon elite a paradigm of behavior that has been passed on from generation to generation for centuries:

Genetics of behavior studies the basics of behavior and all that is associated with it – mental illness, a propensity for divorce, political preferences, and even a feeling of satisfaction with life. Evolutionary psychology is looking for mechanisms through which these features pass from generation to generation. Both approaches suggest that nature and education are involved in the formation of behavior, thoughts, and emotions, but in contrast to the practice of the twentieth-century nature has preference now (CSIKSZENTMIHALYI MIHALY. 2008: 89) .

Something on a much smaller scale is taking place in the Donbas (see Royal Scythia and its Capital). The Russians' inherited sense of superiority, desire to command, and especially their agonalty largely explain Russia's aggressive policies and historical success:

Agon is aimed at achieving victory, this is the target cause of effective force, as a consequence of this victory is valor, centering the ethos of the culture, reflected in the collective memory (YAROVOY A.V. 2010: 36).

However, the self-confidence formed as a result of success does not correspond to the creative capabilities of the Russians, inherited genetically, and this should have dire consequences for them.