Opening of the Great Siberian Route

The Great Siberian Route, as one Russian historian defined it, played a major role in the fate of Russia. It was largely due to the route latitudinally connecting Northern Eurasia that Russia was formed and grew stronger (KYZLASOV IGOR. 2007: 63).

The latitudinal route, which generally passed through the steppe and the border of the forest zone, acquired a decisive significance for the entire subsequent history of pan-Eurasian cultural and political ties from the moment wheeled carts and riding horses appeared. Science still has to find out the periodicity and intensity of its action at different historical stages, to determine the main routes and branches, which over time increasingly covered both steppe and taiga spaces (Ibid).

It turned out to be the backbone that created and still holds the heroic body of Russia. It was and will remain the Eurasian scales of its history (Ibid: 67).

I did not set such a task, but due to the internal logic of my research, I came to the result from which it follows that Russians, thanks to fate, should know the discoverers of this path, but they were by no means their compatriots.

While searching for ancient Anglo-Saxon place names in Continental Europe, I found that a large their part is located in Eastern Europe. One cluster falls on the territory of the former Rostov-Suzdal principality and in the immediate vicinity (see the screen of Google My Maps below). This and other facts gave grounds to assume that in the middle of the 1st millennium AD Anglo-Saxons laid the foundations of Russian statehood. However, there was no mention in the annals about the presence in the principality of the people who differed greatly in language from the rest of the population. Of course, the Anglo-Saxons were not in many numbers, they were only the ruling elite of the tribal alliance known in history under the name of Muroma. However, it is difficult to imagine that they disappeared without a trace among the local Finno-Ugrians and later arriving Slavs. Without making specific assumptions, but only continuing the search for Anglo-Saxon toponymy, I noticed that some European place names have doublets in Siberia and the Far East. After expanding the search area beyond the Urals, it turned out that was not an accident, but a certain regularity. Discovered new Anglo-Saxon place names stretched as a narrow strip from the Urals to Lake Baikal. The reasons that caused the Anglo-Saxons to leave their habitats can only be assumed, since the beginning of their movement beyond the Urals and further to the east is unknown.

The area of the Upper Volga, inhabited by Anglo-Saxons, was, in the words of S.M. Solovyov, the "state core" of Russia, but for the creation of the state, it was prepared in the best way economically, but not politically. After the entry of Rostov-Suzdal land into the state of Kyiv Rus', the local tribal elite could not resist the onslaught of the Kyiv authorities. Thanks to the experience of state building, acquired in close contact with Byzantium, the dynastic rule established in Kyiv understood the importance of economic predominance for political domination. Applying diplomacy and military force, the Kyiv proteges sought to use the capital accumulated in Rostov’s and Suzdal’s nobility during the heyday of trade with the countries of the Arab Caliphate. The main items of trade were slaves from among the indigenous population and furs. As seen below, the affinity for trade was a hallmark of the Anglo-Saxons.

As a stronghold in the newfound land, the aliens from Kyiv laid the city of Vladimir on the Klyazma River, transforming it into a fortress over time. The policy of Andrei Bogolyubsky, who consolidated in the city after Kyiv Prince Yuri Dolgoruky and needed funds for the construction of other cities, caused great dissatisfaction with the local boyars, and in particular, them from the Anglo-Saxon clan of the Kuchkovichs. Their struggle with the prince ended with his assassination in 1174. One can assume that after such an outcome, the Anlo-Saxeons were deemed to migrate beyond the Urals for the better, fearing the revenge of the numerous relatives of the prince. However, in the middle of the 12th century they should have already been beyond Lake Baikal, since Chengiskhan (c. 1155 or 1162 – 1227) was Anglo-Saxon in origin (see Anglo-Saxons in Genghis Khan's Fate). Consequently, some of the Anglo-Saxons crossed the Urals much earlier than the conflict with Andrei Bogolyubsky. However, contacts between the Anglo-Saxons on both sides of the Urals continued, and those who remained in Europe called their Trans-Ural tribesmen sibber, from the Old English sibb "clan" or "tribe." This is the origin of the name Siberia.

On the right bank of the Volga was a state called Volga Bulgaria, the population of which consisted mainly of Tatars, but the ruling elite were Anglo-Saxons. They founded numerous settlements along the banks of the Kama and up to the Urals, to which they gave their names, and they have survived to this day (see Volga Bulgaria). The Anglo-Saxons from both banks of the Volga traded with the countries of the Arab Caliphate. In search of cheaper fur sources, they crossed the Urals and brought their culture there.

In the Middle Ages, the Lower Ob culture was widespread in the north of Western Siberia. To date, the following chronological framework for its development has been established:

- Karym stage (IV-VI centuries);

- Zelenogorsk stage (VI-VII centuries);

- Kuchimin stage (VIII-IX centuries);

- Kintus stage (IX-XII centuries);

- Saigata stage (XIII-XVI centuries).

[GORDIENKO A.V. 2017: 184].

The pace of cultural development is such that the emergence of new components in it should be associated with the influence of migrants. In this case, the Anglo-Saxons had to participate in forming the still insufficiently studied Kintusov stage, which existed on the territory of the Surgut Ob region. This stage's most thoroughly studied site is the multi-layer complex Kintusovskoe-4, which was largely plundered over decades. It includes a settlement, a dwelling, and a burial ground [KONOVALENKO M.V., BALUYEVA Yu.V. 2017]. Judging by the level of metalworking and the quality of claywares, the creators of the artifacts from the Kintusovskoye 4/3 burial ground were people of a higher culture than the autochthonous population, consisting of reindeer herders, hunters, and fishermen (see illustrations below). The products' artistic value explains the sites' popularity among black archaeologists. Some of the lost artifacts were made of silver, as evidenced by the remaining individual finds.

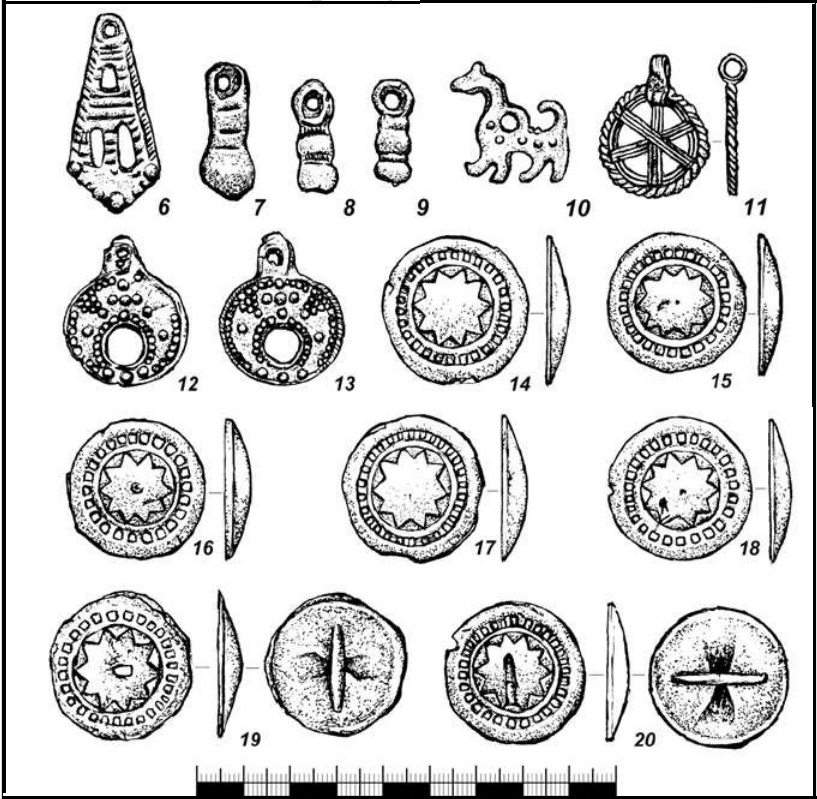

Burial ground Kintusovskoe 4/3. Burial 60.. Illustration fragment [Ibid, Fig. 19, p. 114].

Bronze products (6 – claw pendant; 7-9 – pear-shaped half-pendants;; 10 – ridge pendant; 11 – round pendant; 12-13 – moon pendants; 14-20 – button badge).

The Kintusovsky stage is represented by materials from about 30 sites, consisting of 13 hillforts, three settlements, four dwellings, and six burial grounds. The construction practice and location of the settlements at that stage differed from the previous ones, the settlements were larger, and the burial grounds also differed in their characteristics, in particular, claywares appeared in the burials, which were present in 80% of the graves. Among the general mass, there are burials of warriors with a variety of weapons (swords, sabers, battle axes, defensive equipment), which especially distinguishes the Kintos stage from previous ones [GORDIENKO A.V. 2017: 184-187].

In 2006, a resident of the village of Barsovo, Surgut region, in the floodplain of the Ob River, found a silver jug and donated it to the Surgut Museum of Local Lore (KARACHAROV K.G. 2019: 56).

Справа: General view of the jug. Photo from (Iibid Fig. 2).

The location of the find was examined, but no other archaeological objects were found nearby. The jug is made of silver and soldered from several parts. The following technical techniques were used in production: casting, soldering, embossing, gilding, and blackening. An analogy for the jug can be a Byzantine jug from the village of Pereshchepino (Ukraine) dated 592-602. The study of the decoration of the Surgut jug made it possible to compare its design with a mug found in 1889 in the village of Plekhanov, Solikamsk district, Perm province. There are also other analogies. Karacharov concluded that the jug was made in Constantinople in the 10th-11th century and came to the Middle Ob in the 11th century (ibid., 84-90). It can be assumed that the item was one of many stolen during the looting of the Kintusovsky monuments by lovers of easy money.

Decorations and household items of Kintus time. Illustration fragment [Ibid, Fig. 7, p. 197].

Much more evidence than in archeology about the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Siberia can be found in toponymy. The Direction of searching was denoted by place names in Eastern Europe already recognized as Anglo-Saxon ones, such as Markovo (seven cases), Markova (two cases), Firsovo (three cases), Akhtyrka, Firstovo, Fofonovo, Churilovo (see The Complete List of Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe). Just beyond the Urals, a cluster of “dark” place names was discovered, which with varying degrees of probability can be interpreted using Old English:

Verkhny and Nizhny Tagil on the Tagil River in Sverdlovsk Region – OE. tægel "tail".

Sos'va, two settlements Sverdlovsk Region and one in Beryozovsky district of Tyumen Region, several rivers of the same name – OE. sūsl "suffering, torment", wā "sore, misery".

Firsovo, villages in Rezhevski urban district of Sverdlovsk Region and Pervomaysk district of Altai Krai – OE. fyrs "furze, gorse, bramble" (Genísta).

Chetkarino, a Village in the Pyshma town district of Sverdlovsk Region – OE. ciete "cabin, closet", carr "rock".

Miass, a sity in Chelabinsk Region – OE meos "swamp".

Churilovo, a village in Krasnoarmeisk district of Chelyabinsk Region – OE. ceorl "a man, peasant, husband", Eng. churl.

Markovo, villages in Uvel district of Chelyabinsk Region, Ketovski district of Kurgan Region and Zavodoukovski district of Tyumen Region – mearc "border, end, district", "sign", mearca "determined space".

Shadrinsk, a town in Kurgan Region – OE. sceard "mutilated, chipped" with metathesis of consonants.

Bolshaya Riga, a village in Shumikhinsk district of Kurgan Region – OE. ryge "rye".

Tyumen, a regional center – OE. Tīw, Germanic god of war and mǣnan “mean”, “explain”, “connect”.

Vagina, a village in rural settlement Yurminskoye in Tyumen Region – OE. wagian "to move, shake".

Beyond Tyumen, a strip of Anglo-Saxon place names stretches along the border of forest and steppe and marks a convenient path for further advancement. We can most confidently speak about the following names in the direction from west to east:

Rezanova, a village in Vikulovski distrivt of Tyumen Region – OE. 1. rāsian "explore, investigate", 2. racian "rule, lead".

Firstovo, a village in Bolsheukovski district of Omsk Region – OE. fyrst "first".

Ingaly, a village in Bolsherechenski district of Omsk Region – OE. Ing "name of god", āl "fire".

Atrachi, a village on the shore of the lake of the same name in the Tyukalinsky district of the Omsk region. – OE. ātor, ætrig "poison", cio "jackdaw".

Akhtyrka, a village in Vengerovsky district of Novosibirsk – OE. eaht "advice, council, consideration", rice "power, government, kingdom".

Anglo-Saxon place names in Asia

The territories of the Principality of Pelym and Dauria are tinted in pink.

The map scale did not allow giving the names of all marked toponyms. See Google My Maps

It was considerably more difficult for Anglo-Saxon pioneers than for Russian Cossacks who set out to conquer Siberia, therefore their advance in the direction of Lake Baikal could take several centuries. Even at the turn of the 17-18 centuries, "the whole journey from Moscow to the Amur lasted three seasons, or two winters and one summer, or two summers and one winter… and all this because of the lack of roads" (WITSEN NIKOLAES. 1705). During the long migration, the Anglo-Saxon population had to increase significantly. In each newly created town, migrants left a small garrison, which dissolved later among the incoming Slavic population. The descendants of these people, now called the Chaldones, preserved the legends about their settlement in Siberia even before the appearance of Yermak Timofeyevich and his followers. The origin of their name remains unclear, but it does not have a satisfactory etymology. In this case, it is possible to offer for the interpretation of OE.đearl "strong" and don "do" with this phonological development: th → tš → č. Chaldons switched to Russian long ago but could retain some Anglicisms in their speech.

The autochthonous population of Siberia included many peoples, among which the Anglo-Saxons were very few, but could not go unnoticed due to their originality. Archpriest Avvakum (1620-1682), studying the composition of the population of Siberia in exile, left the following picture:

Into that Siberian kingdom, people who speak different languages live. The first are Tartars, also Vogulichi, Ostyaks, Samoyeds, Lopans, Tunguses, Kirghiz, Kalmyks, Yakuts, Munduks, Gvilyags, Garagilis, Imbats, Zenshaks, Symtsy, Arintsy, Motortsy, Togintsy, Siyantsy, Chalandasy, Kamasirtsy, are many multilingual people in that vast Siberian kingdom… (quoted from ALEKSEYEV M.P. 1932, L).

Among the listed peoples, the mentioned Chalandasy can be associated with the Chaladons, also other information about the composition of the population of Siberia exists, in particular, in the works of Western European authors. The earliest work is a retelling of the messages of the Moscow envoy to the Pope, Dmitry Gerasimov, made by Paolo Giovio and published in 1525. Much more information about Siberia can be found in the "Notes on Muscovy" of the diplomat of the Holy Roman Empire Sigismund von Herberstein (1486-1566), who was ambassador to Moscow twice. This first information is stingy and overflowing with the fiction and fantasies of informants, but analysis can reveal a rational grain in them. First of all, you should pay attention to the names of the people, deciphered using Old English. They may be two Grustinovites and Serponovites, repeatedly mentioned by Herberstein. For the name of the first, OE grist "grinding", "grain for grinding" is suitable. The Serponovites can be associated with the Setrapons mentioned by Paolo Giovio (ibid, 96), and then their name can be understood as "robbers" (OE. set "site, habitat" and riepan "to rob". Although these people have a wild character and a ferocious appearance, they are engaged in trade and buy pearls and precious stones from former merchants arriving from the southern countries (ibid, 104). This characteristic distinguishes them from the majority of the population of Siberia.

While studying the possibility of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Siberia based on historical sources, I became acquainted with the work of the Russian-German historian G.F. Müller (Gerhard Friedrich Müller; 1705 –1783) in two editions (MÜLLER G.F. 1750 and 1938), suggesting that something may be omitted in the second edition. While in Russian service, Gerhard Müller traveled through Siberia and collected extensive material for his work. He dedicated many lines to the Pelym principality, which existed until the end of the 16th century at the site of the accumulation of Anglo-Saxon placenames around the city of Tyumen. If not a single state arose in Europe resulting in self-development (SHUVALOV P.V. 2012, 278), then this could not have happened even more in Western Siberia inhabited by socio-economically backward Ob-Ugric tribes. Although Müller had his ideas about them, corresponding to that time. He mentions the campaign against the Voguls by the Russian governors at the head of an army consisting of “4024 nobles and boyar children.” Accounting for the number of the Mansi people, by which the former Voguls are now called, which does not exceed 10 thousand people, in 1499, when the campaign took place, there should have been significantly fewer of them, even accounting for women and children. Aware of the impossibility of the Voguls fielding an army equivalent to the Russians, Müller writes

The Voguls in those days were more courageous and warlike than at present and caused a lot of concern to the first Russian settlers in the Perm land. It is quite possible that the first campaign was aimed at pacification rather than complete subjugation of these people (MÜLLER G.F. 1938: 203.)

Other travelers, Peter the Great's envoys to China in 1692-95, who became well acquainted with the Voguls on the road, such describe their customs and way of life that it seems incredible that this people could have previously been so brave and warlike as to carry out military campaigns (IDES IZBRAND and BRAND ADAM. 1967, 71-77). Undoubtedly, some other people resisted the Russians under the name of Voguls.

Further, Miller writes that during the campaign “many towns were taken, i.e. small fortifications or places surrounded by fences where they lived, many people were killed and captured, and the most noble, called princes, were brought to Moscow " (ibid., 203-204). Such information can no longer apply to nomads. Perhaps the Voguls saw danger in the Russian advance into Siberia, but they could not help but realize the impossibility of preventing such an invasion. Since the Mansi did not call themselves Voguls, It can be assumed that this name was given to them by other people. It is assumed that this ethnonym comes from the Khanty uoγal, but what this word means is unknown (VASMER MAX. 1964: 330.). If you look for a correspondence to it in Old English, you can find OE. wohhian "to rage", wohhiung "rage". If you look for a match in Old English, you can find Old English wōgian "to woo", "to marry", oli "insult", "contempt". The Anglo-Saxons could marry Mansi women, but this was considered shameful. Thus, the Pelym principality could be founded by the Anglo-Saxons. This assumption is confirmed by the names of some of their princes, which can be deciphered using Old English:

Ablegirim – OE. abal "power, strength", grimm "terrible, cruel".

Tagay – OE. teage "fetters, shackles".

Tawtiy – OE. deađ "death".

The toponym Pelym is quite common in the Ural area, where in the Sverdlovsk Region there is a village and the historical city of Pelym, in the Perm Region – another village, the Pelym River flows into Tavda, the left tributary of the Tobol river (Ob basin) and several others. This name can be associated with OE. fell "fur" and ymb "around". This interpretation is confirmed by the name of the village Puksinka on the banks of the Pelym – cf. OE fox "fox". The basis of the economy of the principality should have been fur as a trade item, reflected in the name of the village Nіkhvor from OE. neahhe "sufficient, plentiful" waru "article of merchandise".

The method of trade between the Anglo-Saxons and the aborigines is indicated by the origin of the Old English mangian "to trade". It is assumed that this word was borrowed from Latin, which contains mango, -ōnis "a fraudulent merchant" (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 214). However, the related words listed in the etymological dictionary of the Latin language mean "deception", "cunning", "insidious", "artificial", "to make good", and are derived from the IE *mang- (WALDE ALOIS, Dr. 1910: 461). For his part, J. Pokorny added to these meanings "good," "nice," "useful thing," "happiness," and "magic cure," citing examples from various languages, while considering the Indo-European *meng- (POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 731) to be the original. As we can see, only the Latin word, and with the definition "fraudulent," relates to trade. The Anglo-Saxons understood trade in the same way, using an ancient Indo-European word, without any knowledge of the Latin language.

The supposed location of the Pelym principality is rich in archaeological monuments. There is no clear classification of them. There are also no available large-scale geographic maps on which the monuments mentioned in the literature could be plotted. They are mainly located in the Konda River basin, along the Irtysh River. In its lower reaches, 18 archaeological sites have been identified. They are located along the banks of small rivers, the left tributaries of the Konda Bolshaya Saga, Yagatka, Mordiega, Pugolskaya (SOBOLNIKOVA T.N. a.o. 2017, SOBOLNIKOVA T.N, KUZINA A.V. 2018.). The description of the state of one of the studied objects is as follows:

Currently, the remains of the houses are practically invisible. The site of the former settlement was heavily overgrown with birch trees, as well as raspberries, rose hips, and nettles. However, the forest still preserves traces of man: abandoned household utensils, wooden foundations of houses and the remains of brick walls from stoves (SOBOLNIKOVA T.N. a.o. 2017: 147).

In Khanty folklore and written sources of the 18th – early 20th centuries, the concepts “town”, “dwelling”, and “heroic place” are used. These were points fortified with a moat, rampart, and palisade, where local rulers lived. Miller described these towns, travelers of the late 19th century claimed that such settlements existed in large numbers along the Konda and its tributaries, and the population in this region was much denser than in their time (SOBOLNIKOVA T.N, KUZINA A.V. 2018: 756). The Book of the Big Drawing gives the following names of fortified “towns” in the Lower Ob region: Chemash, Sherkar, Netsgarkor, Kurmysh-Yugan, Atlym, Karymkar, Emdyr, Kalym, Obskoy Bolshoy (ABAKUMOVA O.S. 2018: 533). Russian historians explain such an abundance of medieval towns by the existence of Khanty political societies (SOBOLNIKOVA T.N, KUZINA A.V. 2018: 757), but do not explain why the population declined so catastrophically the edges. However, if you ask the question “Who really conquered Siberia?”, you can find an alternative answer in the Google search engine. While ongoing excavations provide material for the reconstruction and planning of individual town structures. This was done in detail for the settlement of Endyrskoe I, or the town of Emder (ABAKUMOVA O.S. 2018: ).

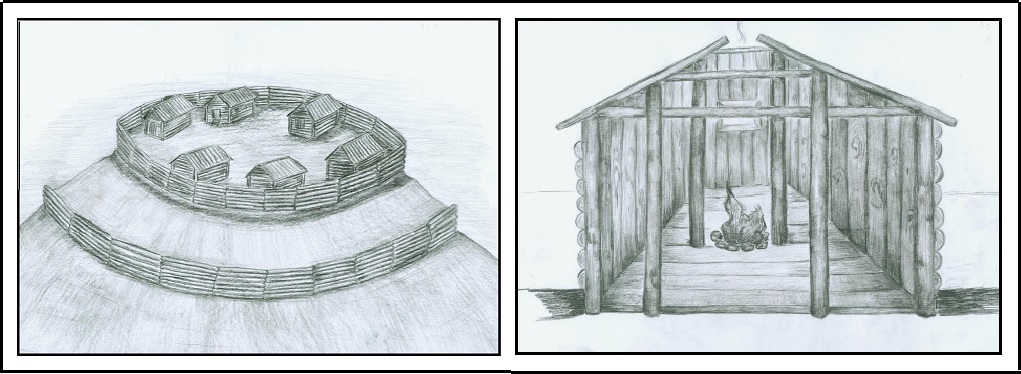

Reconstruction of the "town" of Emder.

Left: General view, right: dwellings. Done by the author. Illustrations from (ABAKUMOVA O.S. 2018: 2018, Il 1 and 2, p. 536).

The design of the dwellings suggests that they were built by Autokhons. The undoubted presence of the Anglo-Saxons in these parts only raises the question of their relations with the local population. Obviously, the fortifications of the towns were caused by the need to protect themselves from aliens. The absence of traces of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons during Miller's journey suggests that they were assimilated among the Russians. However, if we take into account the quoted message by V.N. Pignatti that “when the Russians came, the heroes went into the land and left the Ostyak people” (Sobolnikova T.N., Kuzina A.V. 2018, 761), it can be assumed that the Anglo-Saxons, who were mistaken by the Khanty for heroes, left the Russians further to the east.

The capital of the Pelym principality was Tyumen, as follows from its name, which comes from Old English. Tīw, Germanic god of war and mǣnan “to mean”, “to explain”, “to connect”. However, by the time the ataman Ermak captured the city in 1581 “without much difficulty,” it already belonged to the Tatars and had the name Chimgi. (MÜLLER G.F. 1938: 222). It is noteworthy that even during the movement of his troops, the Voguls behaved peacefully, but the Cossacks, stocking up on food from them, completely robbed them, which could not but cause displeasure. Teaming up with the Tatars, they organized a resistance, but the forces were unequal. While Ermak was fighting with Kuchum Khan, the Voguls, apparently long pushed back by the Tatars to the upper reaches of the Tavda, twice attacked the Stroganovs’ possessions along the Chusovaya River (ibid., 237). Since the Mansi were called Voguls all subsequent times, this name was passed to them from the Anglo-Saxons, who could only organize such military actions. It can be assumed that for some time there was a symbiosis between the Anglo-Saxons and the Mansi. Its traces should remain in the Mansi language. It is difficult to judge the number of Anglo-Saxons and their future fate.

Russian conquest of Siberia in the 17th century passed surprisingly very quickly. After the campaign of Yermak in 1581-1585, it took only about ten years before the township of Tomsk was laid almost two thousand kilometers from the Urals. Soon Tomsk became a Russian strategic and military center in Siberia. Overcoming such a huge off-road distance would be impossible without using waterways however the rivers of Siberia flow in the meridian direction, and they did not contribute to the foundation of Siberia from west to east. Judging by the toponymy, the Anglo-Saxons moved by land, which presented great difficulties in overcoming long distances. To facilitate the advancement of the routes, they were forced to arrange small settlements to provide short-term rest for travelers and horses at night and in bad weather, to eliminate technical problems, etc. Such settlements eventually received the name yam and it is not at all of Turkic origin, as is commonly thought, but developed from OE. hām "house, dwelling", "home". The Anglo-Saxon origin of the word is confirmed by the Manchu word gyamun "postal station". At such stations, some small attendants formed a well-functioning system, managed in an organized manner. This practice spread throughout Siberia, being borrowed by many people. The organization of movement that justified itself laid the foundation for the colonization of Siberia and the Far East long before the arrival of the Russians. Of course, where possible and necessary, waterways were used. For example, this could be the case on the Ob, where the area along the banks was favorable for living, and countless deposits of natural resources lurked in the bowels of the Salair Ridge. The Anglo-Saxons founded several settlements here, which still exist, retaining their original names, sometimes in a somewhat Slavicized form. Among them are the following:

Verkh-Irmen, a village in the Ordynsky district of the Novosibirsk region – OE. iermen "great, strong".

Shadrino, villages in Kalmanski and Tselinny districts of Altai Krai and Iskitim district of Novosibirsk Region – OE. sceard "mutilated, chipped" with metathesis of consonants.

Toguchin, a town in Novosibirsk Region – OE toga "leader", cynn "family, people".

Salair, a town in the urban district of the town of Guryevsk in Kemerovo Region – OE. sala "sale, selling", iere, ōra "ore". The city has a mining and processing plant that produces gold, silver, zinc, and lead.

Shanda, a village of Guriev district of Kemerovo Region – OE scand 1. "shame", 2. "crook, deceiver".

At right: Picture of an owl . Drawing from the site Babyblog.

Barnaul, the administrative center of the Altai Krai – OE. byrne "breastplate", ūle "owl". The plumage of an owl resembles chain mail (see the picture on the right). The city made armor like "owl".

The accumulation of Anglo-Saxon place names around Barnaul suggests that a significant part of the Anglo-Saxons lingered in the upper reaches of the Ob, but no less of them moved to the Yenisei. Their presence in the upper reaches of this river is evidenced by the village under the already mentioned name Shadrino and others:

Tuim, a village in the Shirinsky district of Khakassia – OE. twinn "double, twin".

Bolshaya Irba, an urban settlement in the Kuraginsky district of the Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. ierfa, Ger. Erbe "heritage".

Gagul', a village in Ermakovski district of the Krajanoyarski Krai – OE. gāgul "throat, maw".

However, the existence in the 17th century of a shopping center on the lower Yenisei called Mangazeya, which has no interpretation either in Russian or in the languages of other Siberian peoples, is a big mystery. Meanwhile, it is perfectly explained phonetically and in meaning using OE mangian "trade" and sǣ "море".

On the assumption that the Anglo-Saxons could go down the Yenisei to the sea, an attempt was made to find other place names along its banks that could be deciphered using Old English. This attempt was successful; the following toponyms were discovered:

Galanino, a settlement in Kazachinsky district of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. galan "sing".

Bryanka, a township in Severo-Yeniseysky gistrict of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. berian "bald, uncovered" and –gē "district, area".

Vangash, a township in Severo-Yeniseysky gistrict of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. wang "level, flat", asce "dust, ash".

Velmo, a settlement in Kazachinsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. weolma, "choice".

Sandakches, a settlement in Turukhansky district of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. sand 1. "sand", 2. "bank", āс "oak", "a dugout out oak", ceosan "to choose". The name suggests that here swimmers chose trees from which they could hollow out dugouts on which they could continue sailing. The previous place name could have had the same motivation.

Kellog, a settlement in Turukhansky district of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE. ceol "ship", lōg "site".This name also testifies in favor of sailing along the Yenisei.

Verkhneimbatsk, a village in Turukhansky district of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE imbe "рой пчел", āte "овес".

Igarka, a town in Turukhansky district of Krasnoyarsk Krai – OE ieg "island", ear "wave". The name is explained due to the existence of a large island here.

At left: The island on the Yenisei opposite Igarka.

Different data about the location of Mangazeya exist but it is known the city with the same name was also founded by the Russian authorities. Müller reports the following about this:

At the same time as the city of Turinsk (1600 – B.S.), the city of Mangazeya near the Taz River was also started as follows. Several years before this, from Berezov they tried to visit the places lying from there to the east along the rivers Pura, Taz, and Yenisei. And since a certain Samoyed tribe called Mokase was found near the Taz River, this gave rise to the name of the country there, according to the Russian pronunciation, Mangazeya. This country was best known to ordinary people dwelling near the Dvina and Pechera rivers, both the Russians and Zyrians, because they often went there to buy sable and trade. And some of them gained such courage that from the Samoyed as if they had been sent by royal decree, they secretly collected yasak (tribute) (MÜLLER G.F. 1750: 372).

Thus, there is every reason to believe that Mangazeya was originally founded by the Anglo-Saxons near the sea but due to some reason they left these places before the Russians arrived, leaving no additional traces of themselves. Since the shopping center was already known outside of Russia, it was left with its usual name. The Anglo-Saxons were able to leave the Yenisei because a more promising direction of colonization along the Amur River was opening up. Toponymy says this:

Badarma, a township in Ust'-Ilim district of Irkutsk Region – OE. bād "tribute", earm "poor, miserable".

Sedanovo, a township in Ust'-Ilim district of Irkutsk Region – OE. seddan "saturate".

Kaduy, a village in Nizhneudinsk district of Irkutsk Region codd "bag, sack", wæġ "wey, weight, load".

Daur, a village in Nizhneudinsk district of Irkutsk Region – deor "wild animal".

Zima, a town in Irkutsk Region – OE. sīma "tape, chain, stripe".

Orlik, a village, the administrative center of Okinsky district of Buryatia – OE. orlege "fight, war".

Mandagay, site in the Cheremkhovo district of the Irkutsk region – OE. mann "man", deag "convenient, suitable".

Irkut, a river, the left tribute of the Angara River, Irkutsk, a city – OE. ear “wave”, cuđ “secure”, “friendly”.

Baykal, a lake – OE. wealca "wave", eall ""every, entire". The Old English origin is confirmed by the name of the seven villages of Baikalovo in Russia, also among the Old English place names.

In the settlements founded by the Anglo-Saxons, first of all, men with families were supposed to remain, and young people, not burdened by families, were to move on to the further campaign. On a campaign, they could marry the daughters of the native population. This assumption is confirmed by the similarity Yak. d'axtar "woman" and OE dohtor "daughter". The daughters demanded by the Anglo-Saxons in their language were understood by the Yakuts as women in general. That this word supplanted the original Yakut word can be explained by the fact that the marriage of the Anglo-Saxons to the Yakut was a mass phenomenon. Trade relations were to be established between the aliens and the locals, as evidenced by the correspondence of Yak. soulta "price" and Eng. sold, Yak. čepčeki "cheap" and OE. ceap "trade, price", Yak. tölöö "to pay" – OE. talian "to count". It can be assumed that other borrowings from Old English have also survived in the Yakut language.

The natural resources of Dauria provided good opportunities for the development of this region to the Anglo-Saxons arrived in the Trans-Baikal land. Here they founded many of their settlements, the inhabitants of which were united under the rule of the tribal elite. With this tribe, we associate the Merkits, who played a great role in the fate of Genghis Khan (see the section Anglo-Saxons in Genghis Khan's Fate). Dauria became part of the Mongolian empire, but it represented a fairly independent economic and military unit and remained so until the arrival of Russian pioneers in Siberia. This assumption is supported by the dispatch of a detachment of Cossacks under the command of Pyotr Beketov on reconnaissance from Yeniseisk, built in 1616, not to Dauria, but to the Lena with instructions to gain a foothold on its banks. They had an order to find a foothold on its banks. Moving downstream, the detachment reached the mouth of the Aldan River and Beketov laid Yakut hillfort in these places in 1632. Moscow could not yet provide sufficient forces to conquer the densely populated Dauria. Among the possible settlements founded by the Anglo-Saxons in Dauria, the most convincing transcription of the names are as follows:

Jida, a village in the Dzhidinsky district of Buryatia – OE. giedd "singing, poem".

Fofonovo, a village in the Kabansky district of Buryatia – OE. fā "colorful, motley, potted, dyed", fana "cloth".

Selenga, a village on the bank of the river of the same name in Tarbagatay district of Buryatia – OE syle(n) "morass", -gē "district".

At left: The delta of the Selenga River

Manch. selenge "Iron, cast iron" is not a suitable meaning for the name of the river, but a good phonetic correspondence casts doubt on its Anglo-Saxon origin.

Ust'-Bryan', a village in Zaigraevsky district of Buryatia – OE. bryne "fire".

Kizhinga, a village, the administrative center of the Kizhinginsky district of Buryatia – OE. *cieging "calling" from ciegan "to call".

Dauria, the historical and geographical region within the modern Republic of Buryatia, the Trans-Baikal Krai, and the Amur Region – OE. deor, Eng. deer.

Khilok, a town in the Trans-Baikal Krai – OE. *hillock from hill "hill", Eng. hillock.

Duldurga, a village in the Trans-Baikal Krai – OE. đylđ "suffer", wœrig "tiredness".

Chita, a city, the administrative center of the Trans-Baikal Krai – OE. ciete "cabin, closet".

The Daur people were engaged in farming and cattle breeding, they melted silver ore and traded with the Tungus and the Chinese. The Daurians bartered bread with the Tungus for sable furs and sold them to the Chinese, receiving silk fabrics and other goods in return (SHRENK L. 1883. 163). Knowing about the wealth of Dauria and wishing to appropriate it for the profit of Russia, the voivode (governor) of Yakutsk Petr Golovin sent a well-armed detachment under the command of Vasily Poyarkov to reconnaissances in this country in 1643. Arriving in Dauria, the scouts saw before them such a picture:

There were villages of the Daurians, fields, and arable land in the Zeya River valley. The houses were mostly strong, and spacious, with windows covered with translucent oiled paper. Residents wore silk and cotton fabrics of Chinese origin, received in exchange for furs. The Daurians were engaged in agriculture and had arable land and many livestock. They paid tribute to the Manchus (BALANDIN RUDOLF KONSTANTINOVICH). The site "100 great expeditions").

In reality, it might not have been a matter of tribute, but of trade, or rather an exchange of goods between the Anglo-Saxons and the inhabitants of the region, which the Anglo-Saxons gave their name to (cf. Old English mangian "to trade" and georwe "good, successful, useful, effective" with a metathesis of consonants in this word). The Anglo-Saxon origin of the name Manchzheria is confirmed by the characteristics of the people of this country,

who spoke a language different from the neighboring tribes of Mongolia, who took on different names depending on which clan or head of the tribe that made up the political union was stronger, over the course of centuries, he has repeatedly proven himself in the historical arena (ZAKHAROV I. I. 1875. I-II).

The Daurians met the uninvited guests hostilely and refused to pay the yasak (tribute) to the Russian Tsar. Perhaps the memory preserved legends of the conflict of interests between the Anglo-Saxons and the Rus in Rostov and Suzdal. Poyarkov's detachment was forced to leave Dauria. Descending the Amur River, the unsuccessful scouts reached the Sea of Okhotsk and, moving along its shore, approached the mouth of the Ulya River, and along it went to the Lena basin. In Yakutsk, they returned three years after the beginning of the expedition.

Travelers' stories about the richness of the grain-rich Dauria prompted Russians to send a new, more numerous, and better-armed expedition to conquer it under the command of Yerofei Khabarov. In 1649-1652 years he, acting "with fire and sword", ravaged Dauria and eventually forced the locals to leave their places and seek new happiness under the auspices of the Manchus. From reports on Khabarov’s expedition to the Yakut governor:

And we sailed down the Amur and sailed for two days and night, and destroyed the uluses, all the uluses, and there were sixty and seventy yurts in each ulus, and in those uluses we killed many people and took prisoners, and sailed for seven days from Shingalu through the Duchers, all еhe uluses are large with seventy and eighty yurts, and here all the Duchers live, and the whole place is arable and livestock, and we chopped them down into stumps, and took their wives and children and livestock… [Quoted according to ZABIYAKO A.P. (Ed.). 2017: 44-45].

By the grace of God and the Tsar’s happiness, those Daurs were chopped down from head to head, and then in a detached battle, those Daurs were beaten by four hundred and twenty-seven people, large and small, and all of them Daurs were beaten, who were at the move and who were on the attack and in the detached battle, large and small, six hundred and sixty-one people… […] And that town, by the sovereign’s happiness, was taken with cattle and yasir, and the number of women taken to the yasir, old and young, and girls, two hundred and forty-three people, and small yasyr children, one hundred and eighteen people, and we took from them the horse stock, Daurs, large and small, two hundred and thirty-seven horses, and from them we also took one hundred and thirteen cattle. (Ibid: 50).

Khabarov described the attitude of their Cossacks towards the Duchers, as the Jurchens were called in Russian texts. These people of unknown origin have been mentioned in Chinese documents since the 10th century (Ibid: 39). The Daurs appeared on the banks of the Middle Amur around the 12th-12th centuries. Their ethnogenesis remains a controversial issue. They have survived to this day and live in several regions of China. Their language is Mongolic, and according to anthropological data they belong to the Manchu type (Ibid: 45). There is no exact information about their appearance in ancient times but the names of tribal leaders and princes have been preserved, which can be interpreted using Old English:

Albaza – OE. āl "fire", beag "wreath, crown",

Baldacha – OE. beald "brave", "strong", ciæ "jackdaw", "jay", the name of this bird appears in several Anglo-Saxon personal names, apparently it has a special meaning,

Bebra – OE. bebr "beaver",

Bombogor – OE. wamb, Eng. womb "belly, body", āgan "to own",

Bonbulay – OE. bōn "decoration", būla "decoration", "buckle",

Gildega – OE. gield "service", "sacrifice", "tax", "guild", ege "fear",

Guygudar – OE. geogođ "youth",

Dasaul – OE. dā "deer", sāwol "soul",

Doptyul – OE. deop "deep", "high", walu "scar", "elevation",

Dosiy – OE. dwæs "crazy",

Kokorey – OE. cucu "alive, mobile", reo "wild", "evil",

Kolpa – OE. cleopan "call", "shout",

Lavkay, the most influential prince who had great power – OE. leaf "permission", heah "great", "important", "magnificent",

Olgemzawěl "good", "complete", "reliable", gieman "take care",

Tolga – OE. tulge "strong", "hard",

Turoncha – OE. đuren "beaten", ciæ "jackdaw", "jay",

Tygichey – OE. tyge "movement", "move", scia "leg",

Churoncha – same as Turoncha,

Shilgeney – OE scealga "roach", nē(o) "dead", "corpse".

. Khabarov, despite rich gifts to the tsar, was beaten by his order with a whip for his “exploits” but was still retained in the service. Many historians have written about the devastation of Dauria by the Cossacks. Many historians described the devastation of Dauria by the Cossacks. In particular, L. Schrenk, having his opinion on these events, refers to J.G. Georgi and Ritter in these words:

Georgi repeatedly says that the Daurians, the ancient inhabitants of the region named after it, were engaged in mining here, until, as a result of the conquest of this region by the Russians, they voluntarily left it and moved to the Chinese empire, after which the mining and melting art in Dauria was obliterated. Ritter obviously had the same opinion: he calls the Daurians "a peaceful, cultural people knowledgeable in the mining art". At the first irruption of wild Cossack teams of Khabarov and his successors they retreated from their ore mountains almost without resistance, leaving behind a nearly desert, where, in the aftermath, the Russian mining industry caused secondary colonization in some places (SHRENK L. 1883. 167-168).

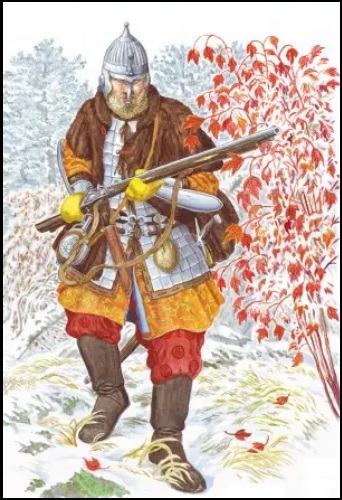

At right: Khabarov's heavily armed Cossack. Historical reconstruction [ZABIYAKO A.P. (Ed.). 2017, Illustrations].

The first Russian “researchers” of the Far East like Poyarkov and Khabarov did not mention the appearance of the local population in their reports. However, another Russian explorer Ivan Moskvitin reported some information about the Daurs. During his hike along the Aldan to the Sea of Okhotsk, he learned from his guides about the existence of bearded Daurs on the Amur. This may speak in favor of their European appearance since the majority of people living here are of the Mongoloid type, who are not distinguished by thick facial hair. Thus, in the process of mixing with the Manchus, the Anglo-Saxons not only switched to their language but also lost to a large extent their Caucasian features. However, connecting the Daurians with the Anglo-Saxons is hampered by the lack of any similarity between Old English and the Daurian language. Many researchers have studied the Daurian language and I checked one of the available dictionaries of it (POPPE N.N. 1930), but I did not find a single Daurian word phonetically and semantically close to Old English.

However, knowledge of the Daurian language did not help anyone to decipher the names of the clans or ethnonyms of the Daurians, which were identified by Japanese and Russian researchers. Their lists are practically identical, they are known (TSYBENOV B.D. 2012, 45). I give a decoding of the Daurian ethnonyms given by the Russians:

dagur – OE deor “animal”, deer.

ono – OE wœona thought", "expectation".

gobol – OE gafol, geafol, gebil "tribute", "tax".

aola – OE eolh “elk”

merdi – OE mǣrd(u) “glory”

hesur – OE hǣs “forest area”, ūr “richness”

dedul – OE dǣde "active"

borgaa – OE biergan “cost”

sodor – OE seodu to sidu "custom".

sudur – OE swæđorian “to move away”, “to disappear”.

uore – OE weorn “many”, “crowd”, “flock”.

kinkir – OE cynn “kin, clan”, “tribe”, cyre “choice”, “election”.

dular – OE dwolian"to wander", "to roam", "nomadize".

samagir – OE sam- “emi-”, eagor "stream", sea".

Since there is much other evidence of the presence of Anglo-Saxons in the Far East, it must be assumed that there were few of them in Dauria and that they eventually assimilated among the local population. Apparently, the Anglo-Saxons, just like in Khazaria, established a xenocracy regime in Dauria and became the heads of individual clans, assigning them their names. Genetic studies can confirm Their presence in this country. Even if there were few Anglo-Saxons, some of their genes should be preserved in their descendants. Chinese geneticists made such studies. They conducted a comparative analysis of the DNA combination of the alleged Daurs with the average combinations of modern peoples living in this region. For the analysis, DNA was taken from 56 Daurs, 24 Evenks, 20 Mongols, and 105 northern Chinese. The results of the analysis showed that the closest genetic parallels are found between the Khitans, Daurs, and representatives of the Benzhen ethnic group from the Chinese province of Yunnan, who consider themselves descendants of the Khitans (ibid.. 2012, 19). Such results of the analysis are natural, but a comparison of the genetic material of the Daurs with the Europeans was not made, because such an idea did not occur to anyone

The European origin of the Daurians can be seen in their housing arrangements and way of life. Russian ambassadors to China write a little about this:

They live in houses built of clay or earth and covered with thin reeds, as do the peasants in many European places. Parts of the walls are whitewashed from the inside with lime. (IDES IZBRAND and BRAND ADAM. 1067: 175).

The development of the theme of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Siberia and the Far East is helped by the search for place names of Old English origin and attempts to correlate them with archaeological data. Over time, new information is discovered and placed on the Google My Map (see below)

Aglo-Saxon place names in Asia and sites of the Kintus stage of the Low Ob culture

On the map, the territories of the Pelym Principality and Dauriya are marked in red. Burgundy dots indicate Anflo-Saxi place names. The approximate distribution area of the Kintus stage is indicated in blue, the sites are marked with blue dots.

The study of the toponymy of the Amur Region allows us to state that some parts of the Anglo-Saxons moved from Dauria downstream along the Amur River. They also named this river, if we take into account OE eam "uncle from the mother's side" and ūre "our". This definition of the Amur has survived to our time in the expression "Amur-father", which exists in the Far East. On the way they founded the following settlements:

Chaldonka, a township in Mogochinsky District of Zabaykalsky Krai and a mountain of Jewish Autonomous Oblast – OE ceald "cold".

Magdagachi, a township in Amur Region – OE. mæg "kinsman", deag "convenient, suitable", āc "oak".

Tynda, a town in the Amur Region. tind "top, point", tinde "tensioned".

Tygda, a village in the Magdagachi district of the Amur Region – OE. tigde "receiver, partner".

Zeya, lt of the Amur – OE. sǣ "sea", "lake", "swamp", ea "water", "river". Zeya is deeper, and wider and has a larger drainage than Amur at the confluence of the rivers.

Shadrino, a village in Mikhylovski district of Amur Region – see above.

Bureya, lt of the Amur – OE. beor "beer", ea "water", "river". Apparently, the river is named for the color of its water. Compare Zeya, similar endings indicate a common origin of the names.

Gassi, a village and a lake in Nanaysk district of Khabarovsk Krai – OE. hæs "woodland", sæ "sea".

Lidoga, a village in Nanaysk district of Khabarovsk Krai – OE. lida "skipper, seafarer", oga "fear, scare".

Ukhta, a village in Ulchinski district of Khabarovsk Krai – OE. uht(a) "twilight, dusk".

G.F. Müller provides interesting evidence of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in his work. He, referring to Abulgazi, reports on the existence of a large city on the river, which is further connected with the Amur:

He says about the Ikran-Muran River that it is very large and flows into the ocean, not far from its mouth there is supposedly a large city of Alaktsin, the name of which means motley or piebald, since the inhabitants of the city do not have any other horses except piebald ones. Many other smaller cities were subordinate to this city. The whole area there is very rich in livestock, and the horses there are of amazing size, etc. In addition, there are rich silver mines there, and the inhabitants of the city do not use any other vessels except silver (MÜLLER G.F. 1938Ö 176).

The above quotation does not differ significantly from the original of 1750, but from the notes to the text it is clear that Müller had in mind the highly educated Khivan Khan Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur (1603-1663), whose main work “Genealogy of the Turks” was translated into many European languages. His transliteration of the name of the city of Alaktsin reflects its original name, which can confidently be associated with OE. ȏleccung "flattery". Thus, there is enough evidence that the Anglo-Saxons were on the Amur, but the toponymy indicates their movement further to the ocean:

Jaore, village on the west coast of the Amur estuary, near the confluence of the Jaore River in the estuary, on the cape with the same name, Nikolaevsky district, Khabarovsky krai – OE. ġear "defense", ġeare, ġearwe "good, sufficient, effective".

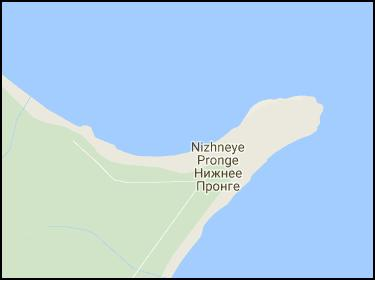

Nizhneye Pronge, a village on the Сape Pronge – OE. preon "awl, needle", the origin of which, like other related Germanic words, is considered unknown (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR, 1989: 542), could be supplemented by OE. –gē "district, area". The Cape Pronge juts out in the sea like a needle (see the map on the right). In some places, it can be read that the name has a match p'ro "small smelt" in the language of locals called Nivkh. But the motivation of such a name for the cape and phonetic correspondence are questionable.

At right: The Cape Pronge.

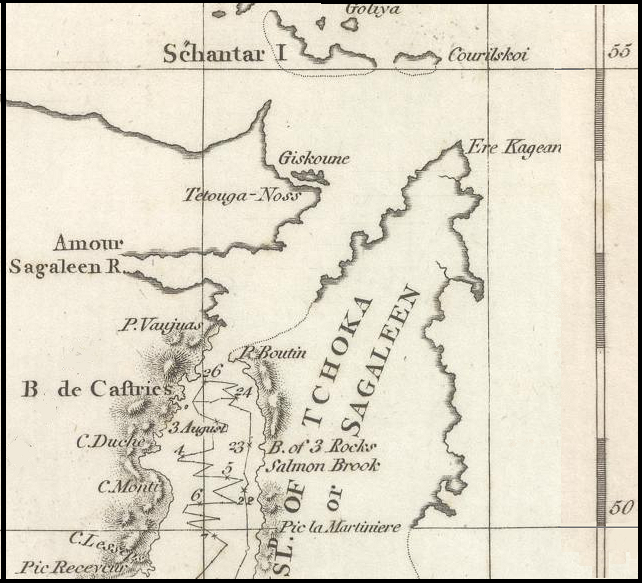

On the other hand, in English and French there is a word of obscure origin prong "tooth, salience", therefore, most likely the name of the cape is based on this word. This name could have been given by English or French navigators or missionaries. However, the explorer of the Tatar Strait La Perouse reached only the De Castri Bay, located 175 km south of Cape Pronge. On the map of the sailing of La Perouse (see below), neither the Cape Pronge nor the Cape Jaore is marked, which implies that these names were given not by him. Investigating in 1797 the Tatar Strait William Broughton confirmed the erroneous opinion of La Perouse that Sakhalin is a peninsula.

At left: A part of The chart of Lapérouse's discoveries in the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk Photo from Wikipedia.

Except La Perouse and Broughton nobody sailed here before Nevelskoy, who in 1849 discovered the strait named after him. Krusenstern, trying to enter the Tatar Strait from the north, did not reach the mouth of the Amur River. As for the missionaries in Primorye and Sakhalin, in particular, their so-called Manchu expedition in 1709-1710 is known.

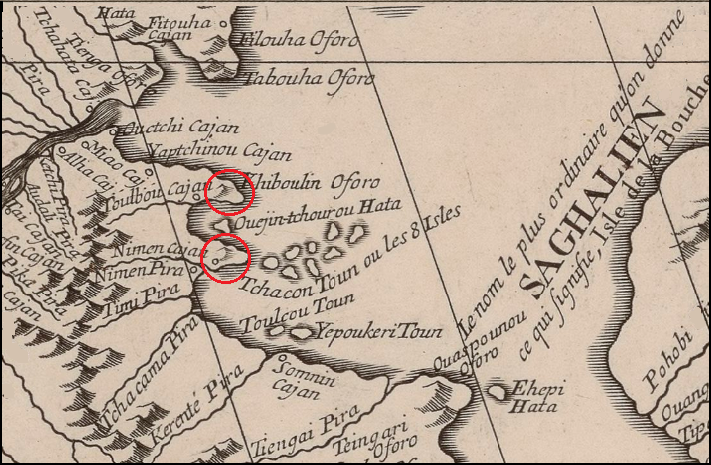

Obviously, according to their data, a map was compiled and included in the atlas of the French cartographer d'Anville (D'ANVILLE JEAN, 1737, 80). On this map, there are many names of rivers and settlements, but Pronge and Jaora are absent, although several others have survived in almost the same form: Tabouha (Tebakh), Pohobi (Pogibi), Pilantou (Piltun), Laha (Lach), etc.

At right: The mouth of the Amur River. Fragment of d'Anville's map.

On the d'Anville's map, the alleged places of the Capes Pronge and Jaore are marked in red. Their names given at that time are completely different. Thus, the names Pronge and Jaore arose later, but their Nivkh origin is doubtful. Probably, the Anglo-Saxons came to Primorye after the missionaries and named several geographical objects by their language. During his voyage, Nevelskoy first heard the names of Pronge and Jaore from the locals. It is highly doubtful that the Nivkh could spell them, but Nevelskoy does not say exactly from whom he heard these names. It is an enigmatical.

On Sakhalin there are also several place names that can be deciphered using the Old English language:.

Trambaus, a village in Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalin district – OE. đrymm "amount", beaw (pl. beaws) "gadfly".

Tangi, a village in Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalin district – OE. tang(e) "tongs, pliers".

Mangiday, a village in urban Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalin district – OE. mangian "trade", dæġ "day".

Nogliki, a township – OE. nō "no, not", glīg "plesure, joy".

Tungor, a villag in Okha urban district – OE. đung "aconitum" (a plant), ōra "bank, edge".

Thus, we have some pieces of evidence that the Anglo-Saxons reached the Sea of Okhotsk along the Amur River. The total number of Anglo-Saxon place names in Primorye and Sakhalin is quite large, and therefore the Anglo-Saxons should have been a significant part of the local population here. Being the people of a higher culture than the Nivkh, the Anglo-Saxons could not dissolve among them without a trace. Nevelskoy and his people had to meet them. Why did not you have any information about this meeting? The solution lies in the fact that Russia could not let the spread of information about some Europeans settling in the Far East before the Russians. The discovery of Nevelskoy provided Russia with the opportunity of convenient access to the Pacific Ocean along the Amur River. The significance of such access was recognized by the tsarist government since the time of Catherine II, therefore, as soon as such an opportunity arose, Russia immediately activated diplomatic efforts to obtain China's consent to join the Amur land. These efforts had success in the conclusions of the Aygun (1858) and Peking (1860) treaties in favor of Russia. But even earlier, the Crimean War (1853-1856) began, during which Englishmen and Frenchmen attempted to gain a foothold on the northwestern shores of the Pacific Ocean. The Anglo-French squadron approached Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, but could not seize it. Nevertheless, fearing a new attack, the Russian command decided to evacuate the garrison at the mouth of the Amur River.

It can be assumed that recognition by Russia of the presence among the aboriginal people of the Primorye a tribe, speaking an unknown dialect of English, could give a reason for the United Kingdom's claim to master this country under the pretext of protecting its compatriots. In such circumstances, the tsarist government considered it best to hide all information about this mysterious tribe from the world community. In his memoirs, Nevelskoy kept silent about contacts with the local population to the south of the mouth of the Amur River, and the circumstances of the voyage along the capes of Pronge and Jaore to the strait named after him were described very scanty (NEVELSKOY GENNADIY IVANOVICH, 1878). All the documentation received from Nevelskoy could be classified as secret, but it would be impossible to hide the existence of an entire Anglo-Saxon tribe. However, the expeditions of L.Ya. Shternberg and V.K. Arsenyev in the Ussuri region and Sakhalin at the beginning of the 20th century found no trace of the Anglo-Saxons, and this casts doubt on their presence in the Far East in general.

Nevertheless, there is the possibility of explaining the complete disappearance of the Anglo-Saxons in the Far East as follows. They could easily mingle with the Ainus, who had well-defined Caucasoid traits and in a few numbers inhabited Primorye and Sakhalin. Before complete assimilation, the Anglo-Saxons were supposed to have contact with some of the Ainu tribes, which could be reflected in borrowings in Ainu from Old English. There is no single Ainu language, the Ainus speak different dialects, which may be more than ten, and most of them are not studied at all. The bulk of the Ainu now live in Japan, and it is there that the best conditions for studying the Ainu language are available. (see the work of Ch. M. Taxami and V. D. Kosarev “Who are you Ainu?”) However, for the first time, a large dictionary of the Ainu language was published in Russia (Dobrotvorsky M. M. 1875). Сurrently, the researcher of Ainu culture and language V.D. Kosarev has compiled a small dictionary of the Ainu language without indicating the source, in which he gives correspondences to Ainu words from Indo-European languages, but the similarity may have other reasons. For example, the similarity of Ainu. tu "two" – Eng. two is because this numeral in Nostratic languages is genetically derived from the second person singular pronoun (see To the basics establishment of numerals in Nostratic language). This can only give reason to consider the Ainu language one of the Nostratic languages. There are other examples of coincidences of words from different Ainu dialects with words of Nostratic languages:

Ainu kara "to make, create", "collect" – Iran. kar- "to do, create, produce";

Ainu kimoro "mountain" – Chuv. kamǎr čul "cliff, block" (čul "stone"), Bashk. kömrö "hump"

Ainu koba "to seize, to possess" – IE kap- "grab";

Ainu kuikui "chew" – IE geu- "chew";

Ainu mat "woman, girl", mati "wife" – IE mātér "mother";

Ainu nana "mom" – IE nana, children's word, e.g. "mommy";

Ainu muus’ "fly" – IE mu-, mus-, "fly";

Ainu poy "small" – Fin. poika, Hung. fiú "boy" a.o. FU;

Ainu puste "lungs" – PSl. pustъ "empty";

Ainu reden "funny" – PSl. radъ "glad";

Ainu reki, rigi "beard" – Iran riš "beard";

Ainu seuni "warm" – Fin sauna "sauna, steam bath";

Ainu tetar "white" – Georg. tetra (თეთრი) "white";

Ainu trekutsi "throat" – Gr. trákhēlos (τράχηλος,) "throat";

Aibu tunni "oak" – Fin. tammi "oak";

Ainu uma "horse" – OT jaby "horse";

Ainu uru "human" – OT er "man".

Ainu-English lexical matches are relevant for our topic. For this purpose, Kosarev’s dictionary was checked with Dobrotvorsky’s materials and as a result of such matches, few were found:

Ainu itaki "speak", "tongue" – Eng talk, the borrowing is doubtful because the Ainu language has enough words of this root;

Ainu kik "beat, hit" – Eng kick (origin unclear);

Ainu patsyns “ticks” – Eng pinch “pinch”, “pin”;

Ainu poni "bone" (Jap. fone "bone") – Eng bone;

Ainu pe/be "thing", "water" – Eng to be;

Ainu se/sex "bunk", "floor", "generally seat", "nest" – Eng set;

Ainu ru, ruu, tru "path, road", "trace" – Eng route.

This number of coincidences is not enough to talk about the influence of the Anglo-Saxons on the Ainu language. If we use Old English for comparison, then their number more than doubles:

Ainu ara/ari "true" – OE ār "honor, dignity";

Ainu seberi-beri "young bear, little bear" – OE bera "bear";

Ainu kiru turn over – OE cierran "turn over";

Ainu okhtena "foreman" – OE eahtia "council", “advice, discussion”.

Ainu re/tre "three" – OE rie "three";

Ainu re, riu "name", "to call" – OE ræd "advice", "plan", "order", "meaning";

Ainu pet "river" – OE pytt "pit", "puddle", "source";

Ainu ranke "separately, in parts" – OE hrung crossbar", "spoke";

Ainu utura "close, together", uturu "interspace" – OE ūtor – "on the other side";

Ainu tanne "long" – OE tān "branch, stick"teon "to pull";

Ainu chip "boat" – OE scip "ship, boat";

Ainu kotan "settlement" – OE cot "hut, shack";

Ainu met "among, amid" – OE miđđ "middle";

Ainu siri "land", "place" – OE sear "dry, sear";

Ainu usiu "slave", "servant" – OE űsse "наш".

There are 23 matches in the list, but some of them may be coincidental, and others may have an explanation other than direct borrowing into the Ainu language from the language of the Anglo-Saxons, which was different not only from modern English but also from Old English. However, even a few examples of obvious borrowings, as evidence of the assimilation of the Anglo-Saxons among the Ainu, explain their complete disappearance in the Far East, since the presence of the Anglo-Saxons there has sufficient evidence. In his time, M.M. Dobrotvorsky did not notice any facts indicating the Anglo-Saxons on Sakhalin, so their complete assimilation should have ended long before the middle of the 19th century.

Ainu group.1904 г.

In the above picture of the group of Ainus of unknown origin, it is clear that some of them have a European appearance without any Mongoloid features that are observed in many Ainu as a result of long coexistence with the peoples of the Mongoloid race.

At present, several hundred Ainu live in Russia and some of them know their native language. A careful study of their language can help restore the final fate of the Anglo-Saxons. But for this, it is necessary to believe that they were present in the Far East.

See the development of the topic Anglo-Saxons in Genghis Khan's Fate.