The Scytho-Sarmatian Problems

The Scythian era was one of the most fascinating periods in the history of Eastern Europe and attracted the attention of many scholars worldwide. A vast amount of material has been collected on the subject, allowing one to create any theory about the origins of the Scythians and Sarmatians, especially if the Cimmerians are also taken into account. Such works attract the attention of the general public with their exoticism and, thanks to their extensive reference lists and rich illustrative material in the form of photographs, tables, diagrams, and geographical maps, make a profound impression. When genetic data is also included, such works are considered the latest in science and technology. Their authors, adopting the status of independent researchers, pit their theories against academic scholarship, which is mired in the abundance of historical data, ultimately leading not only Scythology but also related disciplines into a dead end. You don't have to look far for examples; they can be found online, thanks to the well-intentioned democratization of the scientific process (OOSTHUIZEN JOHAN BAUKE. 2025).

At one time, research into the Scythian-Sarmatian period was particularly active in the Soviet Union, but in fairness, it should be noted that the authoritarian structure of that state prevented academic scholarship from becoming a chaotic jumble of all sorts of sensational theories. Regardless, Soviet scholars relied more on facts and less on their own myths. This is understandable, as the prehistory of modern Europe arose precisely on the territory of that country, now extinct, yet a true product of its development. However, the concept of using the humanities for political purposes, established at that time, has remained and continues to develop, and it largely determines the modern development of Scythology in Russia. Its status beyond the borders of that state is pointless. Inertia is inherent in any science, but it is especially evident in the humanities, which are subject to ideological influences. The histories of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union are good examples of this, but in contrast, in developed countries, the humanities have no influence on their policies, the nature of which follows traditions that have persisted since the days of slavery.

This state of affairs was facilitated by Germany's defeat in World War II, which buried Nazi ideology, but Marxist-Leninist methodology proved exceptionally resilient. The Soviet Union's participation in the victory determined its continued development in modern Russia, changing the essence of the dichotomy established during the Soviet period:

World historical science at that time was divided into acceptable and unacceptable (in Soviet terminology, "bourgeois" or "anti-scientific"). The imperial ideological system of the USSR interpreted the historical past of the country's people in a biased manner. The history of the Turkic peoples was subjected to particularly blatant falsifications (GASSANOV ZAUR. 2002, 16).

Nowadays, in Russia, as elsewhere in the world, "anti-scientific" theories are simply ignored, and this attitude is particularly characteristic of Scythology, as my own experience confirms. In 1999, I published an article in a specialized Ukrainian journal in which I hypothesized the Proto-Chuvash (Bulgar, according to accepted terminology) origins of the Scythians (STETSYUK V.M. 1999). I received a review of the article in a private letter from the now-deceased St. Petersburg archaeologist V.E. Eremenko, from which I present an excerpt:

The Bulgars (Proto-Bulgars) on the Right Bank is, to put it mildly, an unconvincing hypothesis. It is nonsense if we are talking about the 3rd millennium BC (almost 4 thousand years before their appearance in the historical arena!), and even from an archaeological point of view. In general, the entire chain of Scythians-Bulgars-Chuvash does not stand up to the slightest criticism from a historical and archaeological point of view. Linguistic parallels (isoglosses) do not lend themselves to absolute dating at all, so they are hypothetical and cannot be used as confirmation of another, even more shaky hypothesis…

Despite the complete rejection of my research by Mr. Eremenko, I sent him two of my works (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998, 2000) with a request to transfer them to the scientific library of St. Petersburg and introduce them to colleagues. Apparently, St. Petersburg resident A. Yu. Alekseev was not familiar with them, in his work on the chronology of Herodotus' Scythians he does not mention them, just as he does not mention the Turks in general (ALEKSEEV A. Yu. 2003). I became acquainted with this monograph only 20 years later, but before I exchanged several letters with Mr. Alekseev and did not find understanding. I also did not find understanding when communicating with Kyivian resident S. Skory and Lviv archaeologists. Ukrainian archaeologists found themselves captives of the Russian concept of the Scythians.

The question of the Scythians' ethnicity is a key one in ethnogenetic research. However, we encounter a major terminological paradox: the words "Scythian" and "Scythian" can be used in two ways—in a narrow and a broad sense. The narrow sense refers to the ancient Scythian tribes described by Herodotus and other Greco-Roman historians, while the broad sense is used by authors at their own discretion. (LITTLETON C. SCOTT, MALCOR LINDA A. 2000: 3).

However, the main reason is that in Scythology, Russia is trying to set the tone, as in many other areas, and it succeeds. Still in 1952, at the conference of the Institute of the History of Material Culture on the issues of Scythian-Sarmatian archeology, a "final" conclusion was made about the Iranian belonging of the Scythian language based on the "achievements" of Soviet linguists, among which special merit belongs to V.I. Abaev [MELUKOVA A.I. 1989, 37]. Further studies by archaeologists gave reason to believe that the conclusion was hasty. But with all doubts, they can not refute linguists, and now the scythology is practically trampling in place.

The fact that archaeology itself is unable to solve the problem of the ethnicity of the Scythians is understandable. However, linguists are not in a hurry to change their point of view, as shown by the recently published large work devoted to the early Scythian culture, in which there is not a single word about the ethnicity of the Scythians, only a reference to Herodotus, supposedly they came in the steppes of Ukraine from the east (DARAGAN N.M. 2011). The interrelation between archaeologists and linguists in scythology is as follows:

It turned out that the scythologists B. N, Grakov, M. I. Artamonov, A. P. Smirnov, I. G. Aliev, V. Yu. Murzin, and many other bona fide archaeologists got captivated by Iranist linguists though they knew that according to archaeological, ethnographic and other data, Andronov people, Scythians, Saks, Massagets, Sarmatians, Alans were not Iranians, yet since the linguists "proved" their Iranian-speaking feature, they are forced to recognize these tribes as Iranian-speaking. A kind of vicious circle formed: some archaeologists accepted the linguistic version of the Iranian-speaking nature of the named tribes as a scientific truth; and linguists, in turn, based on the results obtained by archaeologists during excavations: as soon as these found objects of the "Scythian type", they immediately declare them to be belonging to the Iranian-speaking tribes (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 4).

It looks rather strange that linguists who are firmly convinced that the Scythians were Iranian speakers do not attach importance to the fact that Herodotus, who knew the Persian language well, does not say anywhere about the similarity of the Scythian language to Persian. This alone should have led them to doubt the long-accepted dogma, but they continued to repeat the authoritative statements of their predecessors, who simply solved the problem. With the inconsistency of linguistics, the scythologists repeatedly came back to the reports of ancient historians and continue to play them in their works, sometimes, lacking new ideas, writing in artistic form for greater persuasiveness (KOLOMOYTSEV IGOR. 2005; MURZIN V.Yu., PETKOV S.V. 2012 a.o). However, no one wonders why ancient historians consider the Scythians and Cimmerians to be different peoples despite their common territory and way of life. They could see the difference between them only in the language. If both of them were Iranian-speaking, there would be no reason to consider them different peoples, as the difference in dialects was elusive for them.

Delusions are replicated and reinforced in the minds of young scholars and have led them astray. Under these circumstances, false representations about the Scythians have existed for decades. The problem is also complicated by immovable national preferences, caused by a special syndrome, one of the manifestations so described:

… – the search for "noble ancestors", the origin of which could exalt the wounded people in their own eyes and the eyes of their neighbors. The Ossetians, in the person of their archaeologists, strongly support their origin from the Scythians, although they are related to the Sarmatians akin to the Scythians (KLEYN L.S. 1993: 67).

Such judgments about the attitude of the Ossetians to the Scythians can be found repeatedly in the specialized literature, but on the whole, the dominant idea about the origin of the Scythian culture and language is such: at the early Scythian time, Iranian-speaking nomads came from Asia and settled in a sparsely populated steppe. Just these nomads spread their cultural influences from the steppes to the population of the forest-steppe. This idea was originally developed due to an uncritical attitude toward the ancient historians, especially Herodotus, and plausible at first glance arguments for its confirmation were found. These include the so-called "Scythian triad" (armaments, horse harnesses, and "animal style" in the art), the spread of anthropomorphic statues, and burial rites.

The hypotheses of scientists have several significant differences, "as the location of the original habitat area of the Scythians and the time of their appearance in the northern Pontic region (NPR), the ethnic and cultural relations between the Scythians and Cimmerians, paths and nature of penetration of both peoples in the Near East, etc." (POGREBOVA M.N., RAYEVSKIY D.O., 1992: 7). It is logical to assume that the common elements in the Scythian culture would have occurred at an earlier stage of its development, but it is not so:

How can we talk about the early Scythian culture, at least on the scale of the Northern Pontic Region, while there are some "Scythian" types present only in the Steppe, and others only in the Forest-steppe? (ROMANCHUK ALEXEY A. 2004, 383).

The apparent incompatibility of certain facts compels some researchers to suggest an autochthonous origin of the Scythian culture, or that it has been experienced by some local influences. The Scythian ethnos arose from a blend of both the local European population and people who arrived from the east (Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Vol 2. 1986). Opinions concerning the Asian ancestral home of the Scythians are controversial and there are serious attempts to locate it in different parts of Europe. Among the many works in this direction, the monograph of M. Pogrebova and D. Rajewski is truly noteworthy. A reasonable criticism of the theory of an Asian homeland of the Scythians, the authors suggested the following solution to the problems of the Scythians' early ethnohistory:

The scene of the most ancient of any well-known events of this history is, not Herodotus Scythia which is NPR, west of the Tanais but, the triangle bounded by the lower reaches of the Volga and the Don and the Caucasus range (POGREBOVA M.N., RAYEVSKIY D.O., 1992: 226.)

In fairness, it should also be noted that some the supporters of the autochthonous origin of the Scythians can express quite extreme views as if the Scythians were the direct ancestors of the Slavs, and even just the Ukrainians (KODLUBAY IRYNA, NOGA OLEKSANDR, 2004). However, the Scythians themselves asserted that the first man who settled in the Black Sea, when they appeared before deserting this country, was Targitay. A thousand years have passed from that time to time to the campaign of Darius on the Scythians (HERODOTUS. 1993: IV, 5,7).

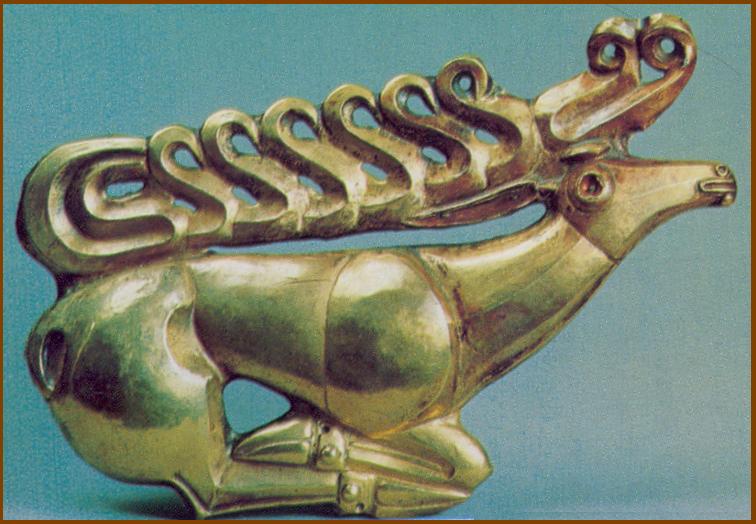

Right: An example of "animal style". The Golden figurine of a deer from the stanitsa of Kostromskaya..

A considerable role of the Asiatic sources concerning Scythian culture dwelt on certain likenesses found in relics of Scythian culture with the artifacts of Central Asia. These similarities adhere to significant arguments pointing to a Central-Asian origin of Scythian culture. Specifically, studying the barrow (kurgan) Arzhan in Tuva, scholars have found out that the samples of the material culture of this barrow can be referred to as the Scythian type manufactured in the spirit of the Scythian animal style. Since these findings allegedly chronologically preceded the Scythian culture in NPR, the assumption of its origins in Central Asia was confirmed based on the conclusion of M.P. Gryaznov:

In our opinion, the eighth seventh century BC was not the end of the Bronze Age and not a transitional or independent ethnocultural period, but the initial stage of the so-called Scythian epoch of early nomads. This was evidenced by the presence of an already well-established Scythian triad in the materials of Arzhan (GRIAZNOV M.P., 1980: 58).

Left: Gold figurine of a horse from the kurgan Arzhan.

Meanwhile, the very method of dating samples from Arzhan focused on, under the assumption of their more recent origin a priori, similar finding in NPR. However, recent discoveries made by Ukrainian archaeologists of Early-Scythian burials, similar patterns of Arzhan, specifically relate to former time (KULATOVA I.N., SKORIY S.A., SUPRUNEBKO A.B., 2006: 58).

For quite some time many archaeologists concluded that the sites of the Eurasian steppe belt can not be regarded as monocultural:

…history of the formation of the Scythian animal style allows us to finally abandon the view that long before the appearance of the Scythian culture in Eastern Europe, it already existed elsewhere in a well-established firm and that its penetration into the area of its occupancy (during the Scythians historical time) is the result of moving the carriers of the culture there. In fact, in under-recorded times, it formed and its different components were formed at different times (POGREBOVA M.N., RAYEVSKIY D.O., 1992: 162.)

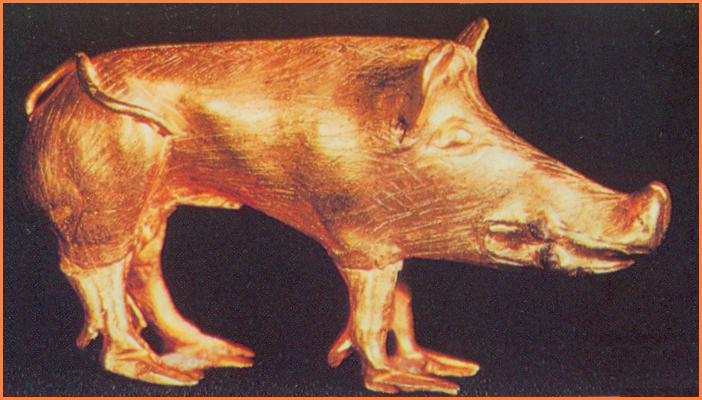

Gold or bronze figurines of animals (deer, goats, boars, etc.), like Scythian ones, were found over a large area, not only in Central Asia but also in the Mediterranean, Minor Asia, and even in West Europe. The imaging of animals by man is defined by his psychology, which has certain common features influenced by surrounding nature with its fauna. Especially popular in the plastic arts of the peoples of Europe was the image of the boar as the personification of physical strength and fearlessness. There is hardly a museum in Europe, from Spain to Romania and from Ireland to Northern Italy where the figurine of a wild boar has not been presented. (BOTHEROYD SYLVIA and PAUL F. 1999, 122). Limiting the "animal style" by a certain region has no reason (see photos below).

Left: Scythian gold figurine of a wild boar from Khomyna kurgan.

Right: Celtic bronze boar figurine from Gutenberg (Lichtenstein).

At the same time, some successful technical solutions (such as horse equipment/gear) spread throughout Eurasia, according to the nomadic way of life is not an important ethnocultural feature. There are also other facts contradicting the idea of the Scythians and their culture originating from Central Asia, particular data, obtained by many anthropologists, gives grounds to speak about the autochthonous population of Scythia:

Scythians failed to appear in South-Russian steppes from the south-east as one can think following the archaeological and linguistic observations, they also failed to appear from the south-west, as compelled to think by the legend brought by Herodotus about their origin, but they arose on that place where they are found by history. Anthropological material does not eliminate the foreign ethnic particulates in the complement of Scythians, however, it gives primary significance to the local sources of their ethnogenesis (ALEKSEYEV V.P., 1989: 177).

The Steppe and Forest-Steppe populations in the Scythian times had inherent features of different morphological types, closely related to the population of the preceding period (Bronze Age). Several researchers repeatedly emphasized this. The idea of an autochthonous origin of the Scythians was upheld by many anthropologists like G.F. Debets (1948, 1971), T.S. Konduktorova (1972), V.P. Alekseyev (1989), S.G. Yefremova (1999), and L.T. Yablonskiy (2000). The study of new materials once again confirms the view of an autochthonous origin of the population during the Scythian time and the formation on its base the population of MCWC (Multi-cordoned ware culture V.S.), Srubna culture, and Belozersk culture both from the Black Sea steppes and from the territory of western and eastern regions (LITVINOVA L.V. 2002, 44)

Archaeological evidence also could confirm the cultural continuity of Pre-Scythian and Scythian times, but archaeologists have no consensus whether the change of cultures in the steppe part of Ukraine was mechanical or monuments of the Novocherkassk-Chernogorov type were the link between the preceding Cimmerian and subsequent Scythian cultures. For example:

… where A Terenozhkin finds a clear and one-time change of cultures, M Gryaznov sees a direct cultural continuity (POGREBOVA M.N., RAYEVSKIY D.O., 1992: 36).

Ambiguity over the question of cultural continuity in the steppes of NPR leads to the fact that even the supporters of the Asian origin of the Scythian culture have no consensus on the issue when the aliens brought it from Asia. Here's one of the views:

Archaeology does not know about any invasion of the nomadic population in NPR, which could correspond to the appearance of the Scythians and the expulsion of Cimmerians, after the spread of the Zrubna culture to the west of the Volga, and the displacement of the preceding Catacomb culture, however, it does not refer to the 8th -7th centuries B.C. but to a much former time the last third of the 2nd millennium B.C. Because of this, the base of the event referred to by Aristaeus and Herodotus may have just changed the Catacomb culture by the Zrubna one, corresponding to the replacement of one people by another, namely, the Cimmerians by the Scythians (ARTAMONOV M.I., 1974: 13).

M. Artamonov saw the continuity between the Cimmerian and the Scythian cultures, assuming both of them belonged to the Scythians. Except for the aforementioned, M. Gryaznov, A. Jensen, and, obviously, other archeologists also had the same opinion (POGREBOVA M.N., RAYEVSKIY D.O., 1992: 36). A. Terenozhkin, denying such succession, believed that the Novocherkassk-Chernogorov relics belonged to the Cimmerians, and the creators of the Scythian culture were "people who came from the depths of Asia, who succeeded in the 7th century B.C. their predecessors the Cimmerians, an aboriginal native of southern European part of the USSR" and that "the Scythian culture was introduced from the outside in a well-established appearance and as if mechanically replaced the old local culture (TERENOZHKIN A.I., 1976: 19). Artamonov's theory is contradicted by historical facts since the conflict between the Scythians and Cimmerians was recorded by ancient and east historians and its reason was associated with the invasion of the Scythians, and the dating of these events was separated from the change of the Catacomb culture by Zrubna one as about 500 years later. By the way, given historians did not know anything about the Scythians in the depths of Asia, they considered them immigrants from Eastern Europe, which is also not in favor of the Terenozhkins theory.

Speaking in general about the Cimmerians, it should be clarified that this name hides two different ethnic groups: the Iranian tribe of the ancestors of modern Kurds and the Adyghe tribe (see the section Cimmerians in Eastern European History). The Scythians could have conflicts with both. First, they encountered the Cimmerians-Kurds in Podolia when moving in the steppe, and already in the steppes enmity could arise between them and the Cimmerians-Circassians. The presence of the latter in the steppes is evidenced by the decoding of the name of the Scythian tribe Auchatai (Αὐχάται) using the Kabardian language: Kabard. eukhyn "to beat, hit" and tay "leyer". Thus, the Auchatai could be part of the Scythians who were defeated by the Adyghe (Circassians).

As Ilyinski and Terenozhkin established, the transition to the Scythian period occurred on the right bank of the Dnieper River, in the course of the evolution of the culture of the Jabotinsky type, approximately in the middle of the 7th century B.C. Most early Scythian time sites are found in the Forest-Steppe up to the Right Bank Forest-steppe, till the Upper Dnister. It is very important. There are only a few tens of Early Scythian burials of the previous period that remain in the steppes, where Scythian culture flourished later (ROMANCHUK ALEKSEY. 2004: 375).

Demographic calculations carried out based on detailed archaeological research allowed us to calculate the quantitative characteristics of the population dynamics of the Scythia steppe, which led, among other things, to a conclusion:

- initial number of Scythian ethnic groups, inhabited the NPR steppes in the 6th. BC can be estimated to be up to 10 thousand men (GAVRILUK N.A. 2013: 268).

It seems unlikely that ten thousand Scythians could have had a major cultural impact on a large population of the Forest-Steppe. For example, in the late 19th century Early Scythian antiquities of 7th-6th century B.C. were discovered only in the present Borshchiv district of the Ternopil Region (the villages of Bilche-Zolote, Sapohiv, Glybochok, Bilche-Zolote, Ivane-Puste, Kotsyubynchyky, Chornokintsi, etc.) in such quantity that in 1876 Archaeological Society was established for their study in Lviv (BANDRIVSKYI MYKOLA, 1993: 3-6).

Taking into account all of the above, one can be surprised by the modern state of Scythology described in these words:

- global ideas, not tested in broad scientific discussions, such as the postulate of "nomadic civilizations" or an unreliably argued version of the Central Asian origin of Scythian culture and the Scythians themselves are surely making their way not only in Russian and foreign audiences but also in textbooks on archeology, including in textbooks published by the Moscow publishing house "Higher School" (YABLONSKIY L.T. 2001: 59).

Having decisively rejected the thesis about the Asian roots of the Scythian culture, we will try to find them on local soil. In our search, we will coordinate the results of our research with historical facts. On the one hand, we concluded that the Turkic peopler, having crossed to the right bank of the Dnieper, moved further in the direction of Central Europe, and one of the tribes, namely the Proto-Chuvashes, settled in the territory of Western Ukraine (see Turkic People as Ceariers of the Corded Ware Cultures). On the other hand, the Proto-Chuvashes were present in the Northern Black Sea region and at times very close to the Scythian. The presence of early Scythian sites in Western Ukraine gives grounds to consider the issue of the connection between the Proto-Chuvashes with the Scythians.

In the 7th century A.D., the so-called Bulgars who inhabited the coast of the Sea of Azov were divided into two parts, one part went to Pannonia where they left their tracks in place names (see the section Turkic Place Names in the Carpathians and Hungary of Scythian Times Place Names in the Carpathians and Hungary). The remaining part/tribes were united with one of the tribal leaders, Kubrat (Kuvrat) into the state known in history as Small Bulgaria, in contrast to Great Bulgaria on the banks of the Volga, which arose later. At about the same time Khazar Khanate began to form (see. Khazars).

After Kubrat's death, Small Bulgaria was divided between his sons Asparukh, Kotrag, and Batbay. This did not help confront the onslaught of the Khazars and eventually led to the collapse of the state. One Bulgar horde migrated to the Danube and took South Transnistria, where their leader, Khan Asparuh created a new state the Danube Bulgaria. Abaev admitted that Asparukh was a Turk, but bore an Iranian name and was trying to find an interpretation for it in the Ossetian language (ABAYEV V.I. 1979: 281). In fact, his name means “chamber of mind” – Chuv. as “mind”, purak “box”. Abaev has many such stretches, however, his authority in the scientific world is strong. In 680, after the unsuccessful campaign of Emperor Constantine IV against Danube Bulgaria, Asparukh's army took Mysia and Dobrogea, populated by scattered Slavic tribes. By combining the Slavs in one state, Asparukh became the founder of Slavic Bulgaria. The second horde, subordinated to Batbai, became part of the Khaganate, and another part of the Bulgars, apparently under the leadership of Kotrag, went to the Middle Volga. Their descendants are the modern Chuvashes. Since it made no sense for nomads to migrate to forest areas, it can be assumed that the bulk of these settlers were farmers.

By the early 8th century, the Khazar Khaganate already possessed a large territory that included the foothills of Dagestan, the steppes of the Kuban, Azov, and partly the Black Sea region, most deal of the Crimea. The young state had to wage a hard struggle for existence with the Arabs, and so most of the Bulgars gradually moved north to the river Kama, where they eventually formed their state of the Volga, or Great Bulgaria (ASHMARIN N.I. 1902, PLETNIOVA S.A. 186: 20-41; RONA-TAS ANDRAS. 2005: 116-117). This state was called Bulgaria since its ruling elite consisted of Anglo-Saxons, whom the Proto-Chuvashes called Bulgars from Chuv. pulkk 1. "flock, herd"; 2. "crowd, gang, flock" and ar "man" (see Volga Bulgars). As a result, later historians, following the example of Herodotus, called the Proto-Chuvashes Bulgars, understood this word as an ethnonym.

This state included also the local Turkic population descended from the carriers of the Balanov culture, as well as the neighboring Finno-Ugric population. According to Ashmarin, the Bulgars were agricultural people and conducted extensive trade with the surrounding peoples, which should testify to their higher culture.

All this compels us to suppose that the Bulgars had to be very numerous people, whose history can be traced by the way its migration from western Ukraine through the Pontic steppes and onto the banks of the Kama River. Consequently, these great people stayed in the steppes of Ukraine during Herodotus' time and could not remain without the attention of this historian. It remains to assume that the Proto-Thuvashi were at least among those peoples mentioned by Herodotus in his “Histories.” Logic suggests that the Proto-Thuvashi must have been the Scythians.

Directions of migration and territory of Scythians

The conclusion that Scythian culture has European roots can be supported also by considerations of a more general nature. For example, the hypothesis of the Asiatic ancestral home of the Scythians based on purely archaeological data might not even have arisen if the ancient historians had not provoked it with their testimonies (POGREBOVA M.N., RAYEVSKIY D.O., 1992: 72).

If, while disputing the genesis of the Scythian culture, scholars were divided into supporters of its Indigenous and Asian descent, the majority of them are united in the opinion of its linguistic identity, not only of the Scythians but the entire population of the NPR during the Scythian-Sarmatian time. The Scythians, Sauromatians, and later Sarmatians are unconditionally considered to be belonging to the Iranian language group. This is a separate issue and is considered in a separate section "Scythian Language".

The result of the research and confirmation of the results was an explanation of modern place names of former Scythia and Sarmatia by languages of the peoples who were descendants of the population at that time. A map of the ethnic composition of Scythia-Sarmatia is presented below:

Scythia-Sarmatia according to place names

On the map, the toponyms of Bulgarish origin are marked with a burgundy color, the azure names are of Anglo-Saxon, red – Kurdish, purple – Mordovian, green – Ossetian, dark green – Chechen, orange – Hungarian, black – Greek. The red line marks the border of Scythia of Herodotus.

The violet rhomb denotes the hillfort of Belsky near the village of Kuzemin, which some scientists associate with the ancient city of Gelon.

The red rhomb denotes a Scythian fortification near the village of Chotyniec in Poland.

More toponymic studies are discussed in section "Prehistoric Place Names of the Central-Eastern Europe".

On the map, the movement of Scythian tribes from western Ukraine in the Pontic steppes can be ascertained, through what is marked by a chain of Bulgarish place names. However, some place names of steppe Ukraine may be attributed to the time of the Khazar Khanate, but not all. The bulk of the Scythians was formed by the Bulgars, the ancestors of the Kurds could be equated to the Alazonians. The Budinoi were ancestors of the Mordvins but the Neuroi and the Melanchlainoi were Anglo-Saxons. According to toponymy, the ancestors of the Mordvins and the Ossetians dwelled nearby. Their neighborhood is confirmed also by linguistics. Therefore, the Ossetians can trace their origin to the Thyssagetai or the Irycai. Holders of other views may try to decipher the same place names using other languages, for example, even Ossetian.

Being on the outskirts of the Iranian world, the ancestors of the Ossetians lagged in their cultural development in comparison with the population of the Pontic steppes. For example, Ossetians borrowed metalworking technology not from them, but from their closest neighbors, the Finno-Ugric peoples. This is evidenced by the Finno-Ugric origin of steel, silver, and copper names in the Ossetian language, they were borrowed by the Ossetians from the Magyars. Even the original name for silver is akin to Persian. nuqra was lost, although V. Abaev stated that, in addition to iron, "the names of steel, gold, and perhaps silver belong to an ancient Iranian layer of the Ossetian language" (ABAYEV V.I. 1958: 481). Only the name of gold has a common Iranian origin. Without etymologizing the steel, copper, and silver names on the Iranian basis, he argued that they were borrowed by the Finno-Ugric from the Ossetians. This statement is highly questionable. Let us consider in the following order:

Steel is called in Ossetianændon. Other Iranian languages have no similar words, while they are quite common in the Finno-Ugric (Udm. andan, Komi emdon, Mansi ēmtan "steel"). In Hungarian, this word can be connected with the name of cast iron öntottvas, where öntott "cast" and vas "iron" (similar to English cast iron). In favor of the proposed explanation is Hung. adz "to harden, temper", which also comes from önt with the addition of the suffix sz, which characterizes multiple actions (ZAICZ GÁBOR. 2006, 163). However the name of the metals in the Finno-Ugrian languages has an unclear suffix -on/an, but it can be preformative for nouns.

Copper is called in the Ossetian language ærkhuy. This word has no analogs in other modern Iranian languages, but there is ǝrǝzata- "silver" in Avesta, akin to Lat argentum "the same". The Finno-Ugric has a similar word but in the sense of "copper": Komi yrgön, Udm. yrgon, Mansi ärgin, Mar. vürgene. Very like on the Mari word Hung. vörheny means "scarlet fever". The transfer of the name stems from the fact that a body is covered with a rash of copper-red color during this disease. However, the Hungarian etymological dictionary (ZAICZ GÁBOR. 2006) explains the origin of the word vörheny from Hung. vörös "red", is phonetically faulty. Following the meaning, the Ossetian word should be borrowed from some Finn-Ugric. The origin of Os. ǽrzǽt "ore" and Pers. arzīz "tin" remains unclear.

Silver in Ossetian is called by ævzist, very like on Hung. ezüst "the same". The other matches in the Finno-Ugric languages are Udm. azves', Komi ezis'. Some authoritative experts believe that this name of silver has a Finno-Ugric origin. The way was so. The Finno-Ugric languages have common names of some metals like Sumerian guškiu "gold": Lapp. vešš'k "copper", Est. vask "copper", Fin. vaski "iron" Moksha us'ke "iron" and others. The shortened form of this same root is available in Udmurt names of silver azves' and lead uzves', where the second partial word ves' meant commonly each metal and the first one was characteristic for it. Thus, at first, the Finno-Ugrians called by the word *ves'k any metal. The Hungarian final consonant k was not lost, as in Udmurt was but turned in t in the original name of silver ezvest, which eventually took the form ezüst. The Ossetians borrowed the name from the Magyars in its original form, but after metathesis of the first two consonants, the word turned into a modern ævzist.

Thus, we can conclude that the names of steel, copper, and silver were not borrowed by the Finno-Ugric from the Ossetians, on the contrary, the Ossetians, familiarized themselves with the new metals through the Magyars, took over their names. About gold is difficult to say because its name is common in similar forms in the Iranian and Finno-Ugric languages, but, although it has Iranian origin, the way it spread is unclear.

Likewise, the Ossetians have no own names also for horticultural crops but borrowed them mainly from Caucasian peoples. The Chuvash, being the ancestors of the Scythians, have their agricultural terminology.

Of fundamental importance in the question of the origin of the Scythian culture is the opinion of Alekseev A. Yu about the existence of "two Scythia":

The peculiarities of the development of Scythian material culture, which allow us to speak of the existence of two large stages: the 7th-6th and 5th-4th centuries BC, as well as changes in its spatial distribution, have been noticed by researchers for a long time, but they are usually interpreted as phenomena that did not affect the nature of the Black Sea nomadic culture as a whole, which at first glance remains monolithic in historical, political, and ethnic terms [ALEKSEYEV A.Yu. 2003: 169].

A. Yu. Alekseev believes that the early Scythian cultural complex, which was more widespread in the forest-steppe zone, "reflected not an ethnic but a certain social system" (Ibid., 192). In light of further archaeological research, the question of the ethnicity of the Scythians is becoming increasingly confusing. Archaeologists are trying to avoid this issue, which is logical in principle, paying more attention to the continuity and similarity of cultures. In this regard, the editorial comments of P.M. Kozhin in P.I. Shulga’s recent publication of the cemetery of the Scythian type in North China are characteristic (SHULGA P.I. 2015). He notes that the cultural areas similar to the Scythian are determined far more in Orenburg and the Trans-Ural steppes which belong to different periods. Speaking about the uniformity of cultures of early nomadic societies, he stressed that it is impossible to say that they all have a certain degree of genetic relationship (how did he come to this conclusion – through genetics? If the markers are there, there is either a relationship or no relationship, simple. I don’t understand what is the problem.) and that this uniformity "does not mean anthropological uniformity of population or original ethnogenetic unity".

Archaeologists not only cannot confidently satisfy the question of the ethnic composition of the population of Scythia-Sarmatia but do not find the reasons for the decline of most sites of the Scythian culture from the beginning of the 3rd B.C., by resorting to the unfounded hypothesis of their destruction by Sarmatians. It seems obvious that the decline of culture resulted in the disappearance of its creators, although this is not necessary. Place names of Scythia convince us that many (tens of) settlements at all times remain permanently inhabited for at least the last two millennia. The vast majority of them are deciphered using the Chuvash language. The lack of Scythian sites in the steppes may indicate the loss of Scythians-Bulgar's traditional nomadic culture after they transitioned to a sedentary lifestyle. At the same time, the place names of Iranian origin (mainly Ossetian) are quite a bit, though the names of Iranian origin constitute a relative majority in the epigraphy of NPR during Sarmatian time. To confirm whether the change of the Scythian culture is possible, focused archaeological excavations must be made in the settlements that have retained their names from the Scythian period.

While academic science is based on the conventional wisdom of the "Altaic" origin of the Turkic peoples but does not recognize the argument of their European ancestral homeland, the attempts to unravel the ethnicity of the Scythians will be a slow and stochastic process. Only with great difficulty will we ever come to the final truth. The work of Zaur Hasanov is indicative in this respect. The author attempts to "reveal the Scytho-Altaic parallels in the field of linguistics, history, mythology, and religion prompting us to select the comparative-historical method of identification as a research technique" (HASANOV ZAUR. 2002:38)

Applying the same method, we arrive at gives a different result from that which Hasanov came to. In studying the Scythian problem, the nationality of the researcher plays a huge role – it determines the preferences of the researcher’s direction ultimately depriving him of objectivity. We see this clearly in the works of the Ossetian, Abaev, and many Turkic-speaking scientists. As a concrete example, we give the derivation of the Turkic ethnonym Guz from the Greek name of the Scythians Σκυθης, made on several pages by Hasanov (Ibid: 122-130). In our studies, we do not deduce the desired result from a variety of different facts, instead, we draw upon one single fact concerning the ancestral home of the Turkic peoples in Eastern Europe. This will determine the direction of the search for solving the Scythian problem. You can be sure that its final solution can be reached differently. A recently published solid work by a Turkish scientist is devoted to the fundamental similarity of the Scythians and the Turks from a cultural, historical, and linguistic point of view, based on a consideration of various aspects of the lifestyle typical of nomadic communities and their agglutinative language (ÖZCAN EMINE SONNUR, Dr. 2020).

… that simplistic understanding of the "Scythian triad" as an ethnic marker contradicts scientific facts and enters into the circle of the Scythian culture deliberately "not-Scythian elements". The "triad" is a category of over-ethnic showing an example of the prestige-sign system of elements, the material culture of the peoples of diverse ethnicities (YABLONSKIY L.T. 2001: 59).