Pechenegs and Magyars

I am presenting this essay with grateful thanks to Volodymyr Bakus for the material support of the research being carried out

Among all the nations that played a big role in the Eastern European events of prehistoric times, the Pechenegs were the only ones not awarded attention in the reviewed here research. In fairness, this omission should be amended at least in the sense of their enigmatic ethnicity. The starting material in searching for the origin of the Pechenegs may be available scanty historical information about their relations with the ancestors of today's Hungarians, whom we call the Magyars, as well as data onomastic data, often used by us in seeking a solution to similar problems.

Judging by the decoding of the names of the Sarmatian Onomasticon, the population of the Northern Black Sea region in the Scythian-Sarmatian time before the beginning of the Hun invasion in 371 AD consisted peoples of Iranian origin, Anglo-Saxons, Proto-Chuvashes, Adyghes, Magyars, Chechens, some Baltic tribe and a small number of Turks of unclear origin. Chechens and Magyars were supposed to be in approximately the same proportion and make up at least 13% of the total population of Sarmatia. A large number of Chechens should not have been left unattended by the then historians and should have been mentioned in their works under some name. It can be assumed that they should be associated with the Akatziri. This ethnonym can be interpreted with the help of Chech. ākha "revenge" and tsIe "fire" (-r – growth of the base, cf. tsIeran "fiery"). The name of one of the leaders of the Akatsir Kuridakh can be deciphered using Chech. kura "proud" and dakhya "not to be afraid".

The ancestral home of the Hungarians, determined using the graphic-analytical method, was located in the ethno-producing area on the left bank of the Don between its tributaries Khoper and Medveditsa (see section Finno-Ugrians and Samoyed tribes). They should be identified with the Savromatians, who, according to Herodotus, dwelled beyond the Tanais, by which he understood the lower Don River and its left tributary, the Seversky Donets. Who are the Pechenegs and where was their ancestral home, we have to find out.

The historically attested names of the Pechenegs were Gr. πατζινακ, Ar. beƺ'enek, Hung. besenyő. The Hungarian name was to be borrowed from the supposed Bulgarish language, in reality, Chuvash (ASHMARIN N.I. 1902). In the Chuvash language, the voiced velar fricative γ developed on the place of the ancient Turkic – k, -g which fell out at the end of the word in later times, as evidenced by the Chuvash loan-word in Hungarian: Hung. borz "badger" from Chuv. *borsuγ, Hung.kút "draw-well" from Chuv. kutuγ (PALLO MARGIT K. 1985, 80). Thus, the Proto-Chuvash name of the Pechenegs could be piçenek and its origin can be associated with Chuv. piçĕn "thistle". One way or another, the Pechenegs, Magyars, and Chuvashes were supposed to be neighbors at some time. According to Ahmad ibn Rustah at the beginning of the 10th century the first of the lands of the Magyar was located between the lands of the Pechenegs and Bulgars and one of the outskirts of the Magyar land adjoined the Black Sea (KHVOLSON D.A. 1869: 25).

The ethnicity of ancient peoples is determined by two factors – the anthropological look and language. Historians generally believe that the Pechenegs were Turks, the anthropological prototype of which was supposed to be Mongoloid. If Pechenegs had evident Mongoloid features, their Turkic ethnicity would not cause any doubts. However, doubts arise precisely about their Mongoloid appearance. The fact that in the steppes from the Volga to the Danube in the burials of nomads of X – the first half of the XIII cent. were being found skulls as Mongoloid and Caucasoid type. During this period mainly the Pechenegs and Oguz (Guzes) could nomadize in this area, and thinking over the ethnicity of studied burials, S.A. Pletniova writes:

What kind of physical types belonged to the Pechenegs and what to the Guzes? Obviously, in this case, you can only make a preliminary hypothesis on the forming of the Pecheneg ethnic group beyond the Volga based on the lived and roamed there Sarmatians. As a result, there was formed Caucasoid steppe type with some admixture of Mongoloid. Mongoloid type, probably, was Oguzian, although clearly expressed their Mongoloid feature are not yet quite understandable for researchers, since, apparently, the two ethnic groups were cooked in one ethnoproducing pot (PLETNIOVA S.A., 2003: 128)

In other words, the Pechenegs were originally Mongoloids, but then somehow mysteriously transformed into Caucasians and thus, anthropology does not give us a clear answer to a question about the ethnicity of the Pechenegs. As for the Pecheneg language, because it has not been preserved, it can only be judged by their own names, recorded in the Byzantine, Slavic, and Hungarian chronicles and documents. It is assumed that numerous runic inscriptions on the territories populated ever Pechenegs, were left just by them. However, attempts to decipher them through the Turkic languages were in vain (PRITSAK OMELJAN, 1970: 98). Similarly, the majority of Pecheneg's own names can hardly be correlated with any of the Turkic languages, although the right is stated in the Byzantine sources that the Pechenegs spoke the same language as Cumans (VASILIEVSKY V.G. 1908: 8). This statement means little in the case of the different ethnicity of Pechenegs and Cumans, as communication between people of different nationalities always premises using a single language. And in this case – what is just it? The Cumans are considered to be a people of Turkic origin, but the well-known names of their khans cannot always be interpreted using Turkic languages. Chronicles distinguish several groups of Cumans: Lukomorian, Burcheviches, Chiteeviches, Burnoviches, etc. (RASOVSKIY D.A. 2012). One might think that various peoples of the North Caucasus and the shore of the Sea of Azov were hidden under the common name Cumans, and among them were Chechens, if we take into account the names of such Cuman khans:

Itlar – Chech. itt "ten", lar "trace", lāрa "to caunt".

Kura – Chech. kura "proud, arrogant".

Toglyi – Chech. tolkkha "burry, crouping in speech".

Among the Polovtsian khans, the Magyars also were present:

Oseluk – Hung. oszlik "to divede". Cf. Ostash

Ostash – Hung. osztás "separation". Cf. Oseluk.

Paslyon – Hung. pasló "pleasure".

The presence of the Magyars among the Polovtsy is confirmed by historical documents. The Hungarian king Bela IV, who knew the legends about the ancestral home of the Hungarians somewhere in the east, decided to organize her search with the help of Catholic monks. He sent several expeditions to the East. The most successful among them was held in 1235. Monk Julian, who took part in it, compiled a detailed written report about the search. It is preserved and it is known from it that in the basin of one of the tributaries of the middle Volga, Julian found people who understood the Hungarian speech and preserved the legend about the departure to the west of part of the tribesmen. In 1237, Julian, already an ambassador, was sent to his fellow tribesmen for the second time. However, by that time the Tatar-Mongols had already begun their invasion and he did not get to the Magyars, so their further fate remains unknown.

Thus, the Cumans spoke different languages and the language of communication in different cases could be different. If you put a specific question about the Pecheneg language, then you need to raise additional evidence. For example, it could be judged by place names left by the Pechenegs, but you need to be confident in their Pecheneg belongings. It is clear that such confidence can not be without knowledge of the Pecheneg language. A vicious circle, the output of which can only be found experimentally with an authentic conception of the dispersal of the various peoples in Eurasia at prehistoric times. However, the dominant idea of their spatial dissemination is not valid. In particular, this applies to the Turkic peoples, which include the Pechenegs. Omeljan Pritsak in his work on Pechenegs, their ancestral home placed "between the Aral Sea and the middle course of the Syr Darya River with the center near the city of Tashkent" (PRITSAK OMELIAN, 1970: 98). Why such accuracy remains unclear. L.N. Gumilyov, in his work on the ancient Turks, mentions the Pechenegs only two or three times, placing them randomly, without explanation, in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya River or in the lower reaches of the Volga River (GUMILEV L. N. 2003). Obviously, his ideas are based on data from ibn Fadlan and Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos. The last, in particular, reported that the Pechenegs first lived near the Volga and Yaik Rivers, and their neighbors were Mazara and Uzes. Subsequently, the Uzes uniting with the Khazars expelled Pechenegs from their own country (GOLUBOVSKIY P., 1884: 34).

In fact, K. Porphyrogenitos talked about the Geikh and Atil Rivers, which can be justly assumed the Volga and Ural (Yaik) by the names, but you can not be sure whether he imagined the location of these rivers and correctly used the names he had heard, because the names of the Volga and Ural were changed repeatedly. He was never in these places and his informant is unknown. The message of ibn Fadlan should be more accurate. He participated in the Embassy of the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir in Volga Bulgaria in 921-922 years. Such a people never existed and Ibn Fadlan did not mention it, but only wrote about the Bulgar king. The Bulgars were the ruling elite of the state on the Middle Volga, which consisted of Anglo-Saxons, and that is why it was called that (see Volga Bulgars). Ibn Fadlan did not delve into these subtleties, but the details of his travel description may be reliable:

Then we crossed after that the river Djam (ie the Emba River, Kazakh Djem,– V.S.), also in the road bags, then we crossed Djahash (ie Yaik, Kaz Djayiq – V.S.), then Adal (ie. Volga, Chuv. Atăl – V.S.), then Ardan, then Varish, then Akhti, then Ardan, then Varish, then Ahti, then Vabna, and all these are big rivers. After that we came to Bajanaks (Pechenegs – V.S.), and they stayed by the water similar to a sea, not flowing, and they are dark brunettes with completely shaved beards, they are poor in comparison with Guzzes. In fact, I saw some Guzzes that owned ten thousand horses and a hundred thousand heads of sheep. (ibn Fadlan TRAVEL TO BULGARIA)

From the report it is clear that the Embassy met the Pechenegs having already crossed the Volga, although there is no way to identify the river called forth. The poverty of Pechenegs said Ibn Fadlan, can only be explained by the fact that they did not have a sufficient number of pastures, it would be completely incomprehensible if they were resident in the endless steppes of Kazakhstan. However, a further description of the journey is somewhat contradictory:

We stayed with Bajanaks for one day, then we went and stopped at the river Djayh, and it is the biggest river what we saw, the widest and with the strongest current (Ibid)

Since ibn Fadlan talked about a "biggest river", it would have to be the Volga, but he called it to Kazakh name Djayiq of the Ural River and this brings to fallacy. Researchers assumed that the Pechenegs definitely had to be beyond the Volga, take into account only this message, without mentioning crossing the Adal at all (MAGIDOVICH I.P., MAGIDOVICH V. I. 1970, 1970: 126-127). Thus, to understand the writings of Ibn Fadlan is impossible without arbitrary assumptions, as well as in many other messages of the ancients, all the more any source should be treated critically. Even today, it is believed that the homeland of Turks was in the Altai, where from they settled in a large area in Asia and periodically massively invaded Europe (Huns, Avars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Tatar-Mongols, etc.) Also the Scythians allegedly came from behind of the Volga but they were referred to as the Iranians. Research ethnogenetic processes using the graphic-analytical method (STETSYUK VALENTYN, 1998) forced to change this picture significantly.

In the process of research, it was found that the ancestral home of the Turks was not in Altai, but in the steppes of Ukraine, from where the Turks migrated not only to the east, where their history is already reflected in historical documents but also westward and to the north. The Turkic people mainly moved to the west and spread their Corded Ware culture in a significant area of Central and Northern Europe (see the section Türks as Carriers of the Corded Ware Cultures). One Turic tribe stayed in Western Ukraine, where they became the creators of the Komarovska culture (XV-VIII cent. BC). At the end of the first third of the 1st mill. BC they began to return to the steppes of the Black Sea region and eventually became known in history as Scythians. The descendants of the Scythians are the modern Chuvash, so we call these Turks the Proto-Chuvashes. Ancient historians attributed to the Scythians, without knowing it, except for the Bulgars, Cumans, some Iranian tribes, as well as the peoples who spoke the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestan languages and inhabited the North Caucasus as well as the Cumans.

The ethnic composition of the population of Great Scythia is confirmed by the data of toponymy when decoding it using different languages it turned out that some place names can be deciphered only using the Chechen language. Purposeful searches showed that there are a lot of them and they are not located randomly, which could indicate an erroneous interpretation, but with a certain regularity. Historical information about Chechens dwelling outside their ethnic territory is absent. Therefore an assumption arises that at some time they were known in history under another name, but similar to the modern one, as is the case, for example, in the identification of the Mordens people mentioned by the Jordanes with the modern Mordvinians. Nothing better than the ethnonym Pechenegs was found. Bearing in mind the possibility of identifying Chechens with Pechenegs, let us briefly consider the place names of the alleged Chechen origin:

Ahaymany (Агаймани), a village in Kherson Region – Chech. axk "abbys", ayman – genitive case of the word ayma "swirl".

Baklan' (Баклань), a village in Bryansk Region, Russia – Chech. bakъluьyn "truthful".

Bekhtery (Бехтери), a village in Kherson Region – Chech. bekhk "debt", ter "pacification".

Berda (Берда), a river flowing into the Sea of Azov – Chech. berd “bank, coast, cliff”. The word berd in the meaning of "stone" is present in the Kurdish language. When deciphering, preference is given to the language in which the nearest place names are deciphered. Besides, it is doubtful this name and the mentioned below originated from a particular Slav. berdo "a detail of the loom," or similar words meaning "hill, mountain" because all of these place names are located in flat terrain, but it may be appropriate for names of rivers with steep banks and settlements on them.

Berdyanka (Бердянка), a village in Luhansk Region – Chech. berd “bank, coast, cliff”. See Berda.

Berdyans'k (Бердянск), a city in Zaporizhzhia Region – Chech. berd “bank, coast, cliff”. See Berda

Bezhin Lug (Бежин луг), a settlement in the Chernsky district of Tula Region in Russia, described in the story of the same name by I. S. Turgenev – Chech. bezhan "pasture, grazing". The semantic similarity of both words of this toponym confirms its Chechen origin. Many other names also originated from the same appellative: Bezhanivka (see) Bezhan, a reserved forest and the village of Bezhan- Tirnevitsa in the south-west of Transylvania in Romania, Bezhaniiska kosa, Belgrade region, Bezhanovo, two villages in Bulgaria, Bezhan, a village in the Bryansk region of Bryansk region, Bezhanov, an abandoned village in the Naursky district of the Chechen Republic. Although the Slavic origin of some of these toponyms is not ruled out, some of them were definitely left by the Chechens.

Bezhin Lug. Painting by I.E. Mitryaev.

Bezhanivka (Бежанівка), a railway station in Luhansk Region – Chech. bezhan “pasture, grazing”.

Bolkhov (Болхов), a town in Oryol Region, Russia – Chech. bplkh “work”.

Dakhno (Дахно), a village in Zaporizhzhia Region – Chech. daьkhni “property, livestock”.

Dashkovo (Дашково), village in Ivanovo, Moscow, Oryol, Pskov, Tver Region, Russia – Chech. dashŏ “gold”, ka 1. "luck", 2. "ram".

Dokhnovichi (Дохновичи), a village in Bryansk Region – Chech. daьkhni “property, livestock”.

Dokhnovy (Дохновы), a settlement in Bryansk Region – Chech. daьkhni “property, livestock”.

Heivka (Geivka), villages in Kharkiv and Luhansk Region – Chech. ge “span”.

Kairy (Каїри), vallges in Kherson and Odesa Region – Chech gІayrē “island”.

Kairka (Каїрка), a village in Kherson Region – Chech. gІаyrē "island"

Kakhovka (Каховка), a city in Kherson Region, a village in Odesa Region – Chech. kъaxьō " bitterness "

Kartanash (Картанаш), a railway station between Debaltseve and Popasna in Luhansk Region – Chech. kxartanash is plural of kxartan "rash".

Kuyal'nyk (Куяльник), an estury and a village in Odesa Region – Chech. kъuьylu "narrow, tight".

Lamzaky Velyki (Великі Ламзаки), a village in Odesa Region – Chech. lam "mountain", zagIa "offering, gift".

Matreno-Gezovo (Матрено-Гезово), a village in Belgorod Region – Chech. marta “breakfast, snack”, gIēzō is the ergative case of gIaz “goose”. Cf. Urus-Martan, a town in the Chechen Republic.

Mezenka (Мезенка), rivers, lt of the Oka River, lt of the Volga, and lt of the Moskva River, lt of the Oka River – Chech. mezan “honeyed”.

Mezentsevo (Мезенцево), a townin Kaluga REgion, Russia – Chech. mezan “honeyed”.

Mozdok (Моздок), a village in Uvarov district of Tambov Region and a town in Kursk Region, Russia – Chech moz "honey" and dog "a heart, core". This deciphering is confirmed by the location of the city of Mozdok in North Ossetia near the Chechen Republic.

Sabynino, a village in Yakovlev district of Belgorod Region, Russia – Chech. sābin "soapy".

Saky (Саки), a town in the Crimea – Chech. sakx "observant".

Tarsalak (Тарсалак), a village in Zaporizhzhia Region – Chech. tarsal " squirrel".

Tomaryne (Томарине), Chech. tōmar "reed".

Tuskar' (Тускарь), a river, rt of the Seym River and Lake Tuskar' near – Chech. tuskar “basket”.

Yerzovka (Ерзовка). There are about twenty such place names scattered over a large area in Russia. Most of them may come from Lith. erzinti "excite", but in the Volgograd and Tambov Regions the Balts could not be therefore there they can be associated with Chech. erz "reed".

Yevlan' (Евлань), a village in Oryol Region – Chech. evla "village".

Yevlanovka (Евлановка), a village in Lipetsk Region – Chech. evla "village".

Yevlanovo (Евланово), a village in Oryol Region – Chech. evla "village".

Yevlashi (Евлаши), villages in Grodno and Brest Region of Belarus, and in Oryol Region – Chech. evlash "villages".

The possibility of the Chechen origin of each of the names can be discussed, but there is a particularly questionable cases that are given just not to lose sight of them:

Lugan', Luganka, several rivers and settlements in Ukraine and Russia – the names look as Slavic but the suffix -an' is more suitable for the name of a place, it is not typical for hydronyms. For the interpretation of place names can be considered Chech. logan, an adjective from the log "neck".

Sudzha, a town in Kursk Region, Russia and a river, rt of the Psel River – similarity to several names of settlements and rivers Sunzha suggests their common origin. The Sunzha River in Ingush, akin Chechen, is called Sholzha khiy that is translated as "ice water" (Ing. sha "ice", shiyla "cold", Chech. Shēlō "colgness", Ing. khiy, Chech. khi "water"). That is the origin of the name is clearly Nakh and the original name of the river had to be exactly Sholzha khiy and the forms Sunzha and Sudzha were evolved from it.

The territory of the spread of alleged Chechen place names is largely coincides with the territory populated by the Pechenegs at a certain time:

At the end of IX century Pechenegs, as it is known, dominated the whole space of the Black Sea steppes from the Don River to the area Etelköz, ie approximately till the Dniester (RASOVSKIY D.A., 2012, 41)

It is characteristic that just direct evidence of settlements of the Pechenegs can be found in places of a multitude of Chechen place names. Some of them lead in this work Omeljan Pritsak:

Pechenehy (Печенеги), a town in Kharkiv Region.

Pechenezhets (Печенежець), a forest near the Rosava River, lt of the Ros', rt of the Dnieper.

Pechenezhin (Печенежин), a town in Kolomia district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region.

Pechenihy (Печеніги), a hill near the town of Bibrka in Lviv Region.

Pecheniky (Печеники), a village in Starodub district of Briansk Region, Russia.

Pecgenia (Печеня), a village in Zolochiv district of Lviv Region.

Pecheniuhy (Печенюги), a village in Novhorod-Siverski of Chernihic Region.

The greatest density of supposed Pecheneg toponyms falls on the territory of the Chernihiv Principality, and southeast of this cluster along the Seversky Donets stretches a chain of settlements of the Saltovo-Mayatsky culture that existed in the 8th-10th centuries. They can be a link in the defensive line as a defense of the local population from attacks by the Khazars. According to the chronicle, in later times the Chernihiv Principality was often "managed by the Polovtsies", who also participated in the campaigns of local princes against Smolensk and Kyiv (ISTORIYA SSSR. 1966: 593). Among these Polovtsies could be Pechenegs, as well as Kurds and Adyghes (see Kurds at the Origins of Lithuanian Statehood). The good relations of the principality with the Polovtsies are very doubtful because it waged constant wars with them. At the same time, the more powerful union of the Polovtsian tribes forced out other nomads from the steppes, and they sought refuge in the northern land. These numerous newcomers became allies of the Chernihiv princes, and their naming "Polovtsies" in the Kievan chronicles should be considered an understandable generalization of the "pagans".

The annalistic mention of the participation of the Pechenegs in the campaigns of the Siverian princes explains the spread of Chechen toponymy over a wide area of Russia. There are few alleged Chechen names north of the Novgorod-Seversky principality, but their convincing transcript says that these are not accidental coincidences. For example, in the northern regions of Russia there are five from eight present in East Europe settlements containing in their name the root evla or evlash, well matching Chech. evla "village" (pl. evlash). Some others could be deciphered only using Chechen, and not Russian or Finno-Ugric languages. Obviously, the mentioned campaigns contributed to the resettlement of the Pechenegs to the north. Noteworthy is the presence in Russia of the names of the settlements of Chechenino, Chechen, and Chechino (five cases). So they could be called because they were inhabited by Chechens. In this regard, it can be assumed that the name of the Pechenegs, formed in the south, turned into "Chechens" in the northern regions, and it was this word that was fixed to the Pechenegs and has survived to this day for the name of the Chechens. This should indicate that the Chechens were identified by the Russians as specific people continuously since the time of the Pechenegs. The Pechenegs did not have their own written language and therefore did not leave written evidence of their history, but they were given to us by onomastics and archeology.

On the territory of Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, there are several toponyms containing the root gapon (Gaponovo, Gaponovka, Gaponovychi, Haponivka, a.o.). These names come from the Chech. gIap (genitive gIōpan) "outpost". The surname Gapon is also quite common in Ukraine (see below). In the village of Gaponovo (Krasnooktyabrskoe), Korenevsky district, Kursk region, a hoard of the early Middle Ages was discovered. Its study by archaeologists gave grounds to assert that it belongs to an ethnocultural community of mixed origin. The population of the territory of this community was subordinate to the Khazars, which presupposes certain North Caucasian cultural influences (GAVRITUKHIN I.O., OBLOMSKIY A.M. 1996: 148).

At right: Artifacts of the Gaponovo hoard (Photo of the title page of the book "Gaponovo Hoard and its Cultural and Historical Context" (GAVRITUKHIN I.O., OBLOMSKIY A.M. 1996).

Caucasian motives of the artifacts attract attention, which is noted by archaeologists. In particular, T-shaped linings are widespread in Crimea and the North Caucasus ( ibid , 26). Metal products could not belong to the Slavs, who at that time were distinguished by technological backwardness in metalworking (NEFEDOV SERGEY. 2010: 86).

From historical sources it is known that in the 9th cen. the Magyars populated Levedia, somewhere between the Don and the Dnieper. In any case, this is not far from the ancestral home of the Hungarians, which was noted by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, who called the Magyars Turks:

The nation of the Turks had of old their dwelling next to Khasaria, in the place called Lebedia after the name of their first voivode, which voivode was called by the personal name of Lebedias, but in virtue of his rank was entitled voivode, as have been the rest after him… The Turks were seven clans, and they had never had over them a prince either native or foreign, but there were among them 'voivodes' of whom first voivode was the aforesaid Lebedias. They lived together with the Khazars for three years and fought in alliance with the Khazars in all their wars (CONSTANTINE PORPHYROGENITIUS. 1961: 38).

From their ancestral homeland, the Magyars migrated in opposite directions. Konstantin Porphyrogenitus wrote that this happened after a lost battle with the Pechenegs and pointed out that in the east, part of the Magyars settled in the regions of Persia (ibid.). In fact, this unit moved north along the right bank of the Volga. This path is marked with the following toponyms:

Karnovar (Карновар), a village in the Neverkinsky district of Penza Region – Hung. káron vár "ruined fortress".

Kanasayevo (Карасаево), avillage in Nikolayevsky district of Ulyanovsk Region – Hung. kanász "swineherd".

Ulyanovsk (the former name Sinbirsk (Синбирск)) – Hung. szín "coloured", pír "blush, flush".

Undory (Ундоры), a village of Ulyanovski district and Ulyanovsk Region – Hung. undor "disgust".

Syukeyevo (Сюкеево), a rural locality in Kamsko-Ustyinsky District of the Republic of Tatarstan, – Hung. sük "narrow".

Apastovo (Апастово), a town, the administrative center of Apastovsky district of Tatarstan – Hung. apaszt "to decrease, reduce".

Moving to the left bank of the Volga, the Magyars settled in the basin of the left tributaries of the Kama and became the creators of the Kushnarenkovo and Karayakupovo cultures widespread there. Historical documents testify that the Magyars moved further east and entered the vast territory of various Turkic peoples:

… at the turn of the early and developed Middle Ages, the Eastern Magyars were closely interconnected with the vast nomadic Turkic world of Eurasia. Turkic-language sources (which are oral in origin) provide important information about the early contacts of the Kypchaks and the Eastern Magyars, dating back to about the 9th-10th centuries, which took place in the Volga-Ural region (KUSHKUMBAYEV A.K. 2018: 39).

The rest of the Magyars in the ancestral home passed to the right bank of the Don in Scythian time. In the interfluve of the Don and Seversky Donets, there is an accumulation of toponyms decoded using the Hungarian language:

Gotalskiy (Готальский), a hamlet in Millerovo dstrict of Rostov Region – Hung. gátol "to hinder".

Mastyugino (Мастюгино), a village in Ostrogozhsky district of Voronezh Region – más "other", tőgy "udder".

Setraki (Сетраки), a hamlet in Chertkovo district of Volgograd Region – Hung szétrak "to spred, place".

Rossosh' (Россошь), a town and a village in Voronezh Region, a village and a hamlet in Rostov Region, several rivers in the Voronezh, Belgorod, and Rostov Regions, in the Krasnodar Kray – the origin from the word sokha "plow" is too far-fetched, a large number of toponyms and the fact that a similar name is found in the Transcarpathian Region on the border with Hungary makes it take the Hungarian origin of the word– Hung. rossz "bad", -os – the noun suffix.

Shebekino (Шебекино), a town in Belgorod Region – Hung. sebek "wounds".

Urazovo (Уразово), a town in Valuysky District of Belgorod Region – Hung. úrak "gentlemen".

Yeritovka (Еритовка), a hamlet in Millerovo dstrict of Rostov Region – Hung. ér "stream", iz "joint".

It was in the space of dissemination of these toponyms, at least partially on the territory of the Chernihiv Principality, that Levedia should have been located. Hungarian toponyms are interspersed with Chechen Kurdish ones and, obviously, the Magyars, like the Chechens and Kurds, were in the service of the Chernihiv princes and took part in their campaigns to the north. This can be evidenced by a chain of alleged Hungarian toponyms:

Terepsha (Терепша), a village in Zolotukhinsky of Kursk Region – extinct Hung. terepes "vast" (ZAICZ GÁBOR. 2006: 740). Terebes is an integral part of many place names on ethnic Hungarian territory.

Retinka (Ретинка), a village in Pokrovsk district Of Orel Region and a town in Shchyokino district of Tula Region – Hung. réten "on meadow".

Ferzikovo (Ферзиково), a town in Kaluga Region – Hung. férges "wormy".

Valuyki (Валуйки),a town in Belgorod Region, a village in Volokolamsk district of Moscow Region, and a village in Staritsky district of Tver Region, Russia, a village in Starobilsk district of Luhansk Region – Hung. vályú "a manger, trough" (from *vályuk, cf. Chuv. valak "gutter, trough"), maybe also "hollow, ravine", -i – adjective suffix

Yerdovo (Ердово), a village in Medyn district of Kaluga Region – Hung. erdö "forest".

Driven out of Levedia by the Pechenegs, the Hungarians moved across the steppes of Ukraine and further along the Dniester to the Carpathian region. Hungarian place names marks this path and their small cluster in the middle reaches of the Southern Bug suggests that some of them settled in these places:

Holdashivka (Голдашівка), a village in Bershad district of Vinnytsia Region – Hung. hold "moon".

Holma (Гольма), a village in Balta of Odessa Region – Hung. holmi "a thing".

Kidrasivka (Кідрасівка), a village in Bershad district of Vinnytsia Region – Hung. kiderül "to emerge".

Konceba, a village in Savran of Odessa Region – Hung. konc 1. "a peace of meat", 2. "gain, spoil". The Hundarian word was borrowed from a Slavic tribe of Ulichi or Tiverthsi populated this area (Sl. kąs "a piecxe)".

Savran (Саврань), a town in Odessa Region – Hung. sarv "horn".

Sabadash (Сабадаш), a village in Zhashkiv district of Cherkasy Region – Hung. szabadas "free". The word is clearly borrowed from the Slavic svoboda "freedom", but the borrowing did not take place in the new homeland of the Magyars, but in Levedia, when they were neighbors of the Ukrainians.

Salkovo (Сальково), a town in Hayvoron district of Kirivohraf Region – Hung. sálka 1. "a splinter", 2. "fish bone".

Farther Hungarian place names interspersed with Chechen goes along the Dniester River to the Western Ukraine, including such as Vendychany (Hung. vendég "guest"), Korman' (Hung. kormány "rudder"), Kelmentsi (Hung.kelme "textile"), Boryshkivtsi (Hung. borús "cloudy, morose") a.o.

The place-names of Hungarian origin contradicts the chronicle report that in 898 the Magyars passed by Kiev, moving towards the Carpathians. Doubts about the possibility of such an event were expressed by Artamonov, believing that the people of Kiev "had vague memories of one of the Magyar raids on Russia, which are reported by Arab writers."(ARTAMONOV M.I. 1962, 348).

The presence of the Magyars in Western Ukraine is confirmed by names containing the roots of Ugr (Uhr), Uger (Uher) from Ukr. Uhor "Hungar": the villages of Uhryniv in Sokal district, Lviv Region, in Horokhiv district of Volyn Region, in Tysmenytsia district of Ivano-Frankivsk Region, the village of Uhryn Chortkiv district, the village of Uhrynkovtsi in Zalishchyky district of Ternopil Region, the village of Uhersko (formerly Ugriny) in Stryi district, the village of Ugry in Gorodok district of Lviv Region. In addition, the villages of Green Guy in Gorodok district and Nagirne in Sambir district of Lviv Region, previously having the names Uhertsi Vinyavski and Uhertsi Zaplatinski respectively.

There can be found in the area of these place names such ones which can be decoded by means of the Hungarian language. For example the villages Libohory in Turka and Skole districts of Lviv Region have good Hungarian match in the name of the plant Stellaria media (Hung. libahúr). The following place names also can have Hungarian origin:

Cherlany (Черляни), a village in Horodok diatrict of Lviv Region – Hung. czere "change", leany (lány) "a girl". When dominant exogamy in ancient times a custom to marry a girl of another tribe was practised. The village of Cherlany could be a place where Hungarians and Ukrainians of neighboring villages exchanging girls for marriage.

Tershakiv (Тершаків), a village in Horodok district of Lviv Region – Hung. térség "space, area".

Terebezhi (Теребежі), villages in Brody and Busk districts of Lviv Region – extinct Hung. terepes "vast".

Tsykiv (Циків), villages in Busk and Nostyska districts of Lviv Region, The village of Tsykova in Chemerovets district of Khmelnytski Region – Hung. cikk "a thing, commodity". The origin of this word is supposed German (Zaicz Gábor. 2006) from infrequent Ger. Zwick "a wedge (clothing)". This is a very questionable parallel according the sense. Perhaps the Hungarian word, as well as Rus.tiuk orinate from Turk. tüg "a bundle".

Voluyky (Волуйки), a village in Busk district of Lviv Region – Hung. vályú "a manger, trough", cf. Valuyky.

The surname Telefanko (Телефанко) is very common in villages of Popovychi in Mostiska district and Drozdovychy in Gorodok district of Lviv Region. It can be found also in other villages and towns nearby. This name stands for good with the help of the Hungarian language – Hung. tele "full, filled up" and fánk "a donut". In the same places, the surname Vengrin is very common. This is additional evidence that the Magyars remained in these areas before the arrival of the Ukrainians, and then they were assimilated by them.

There are so many place names of alleged Hungarian origin in the Upper Dniester basin and the surrounding area that the historical Etelköz, should be placed here. At the same time, the Magyars lived in close proximity with the Ukrainians for a long time, as evidenced by Ukrainian borrowings in the Hungarian language. In this regard, the name of the city of Zhydachev is indicative (the first references as Udech or Zudechev). The primary name is well deciphered with the help of the Hungarian language – Hung. üde "fresh" and cséve "spool", cső "pipe". At first glance, there is no semantic connection between these words, but in fact it is. Hungarian words are borrowings from the Slavic language and the original word has the meaning "duct" (ibid: 123). In the Ukrainian language there is the word tsivka "trickle", therefore, the original Hungarian word and the borrowed from Ukrainian are combined in the name of the city, and the name can be interpreted as "fresh stream".

Zhydachev is located on the Stryi River, the valley of which leads to the Verecke Pass, on which stands a monument in honor of the passage of the Magyars through it during the “acquisition of the homeland”.

At left: Verecke Pass. Memorial of the 1100th anniversary of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in 895

The Magyars used the path along the Stryi valley several times, as evidenced by the names of the settlements along the river, which can be translated using the Hungarian language – Turady, Teisariv, Semigyniv. There is also the village of Uherske.

Constantine Porphyrogenitus described the reason for the resettlement of the Magyars beyond the Carpathians as follows:

And when the Turka had gone off on a military expedition, the Pechenehs… came against the Turks and completely destroyed their families and miserably expelled thence the Turka who were guarding their country. When the Turks came back and found their country thus desolate and utterly ruined, they settled in the land where they live to-day 9CONSTANTINE PORPHYROGENITUS. 1967:40)

Not only in place names did the Pechenegs and Magyars leave traces of their former settlements. As shown by a study of the code of Ukrainian surnames, quite a lot of them can have Hungarian and Chechen origin. Information on their availability and dissemination throughout the territory of Ukraine is provided by Map of Dissemination of Surnames of Ukraine. Unfortunately, such a map has not been compiled in Russia, so it is not possible to judge how widely the names of Hungarian and Chechen origin are represented in Russia. In Ukraine, among the indigenous population, one can encounter quite a lot of surnames of Hungarian origin. Most of them are in Transcarpathia, but they cannot indicate the presence of Hungarians in Ukraine in ancient times. However, outside Transcarpathia, more than two thousand carriers of the surname Sabadash (Сабадаш) were recorded, while the phonetically correct Hungarian form of Szabados (888 cases) occurs almost exclusively in Transcarpathia. On the contrary, the surname already mentioned Telefanko (Телефанко) is recorded only once in Transcarpathia, while in the Lviv region there are 49 carriers of this surname. Hungarian surname Lakatos Лакатош) evenly disseminated throughout Ukraine – Lviv (16 carriers), Novi Sanzhary district of Poltava Region (21), Putyvl district of Sumy Region (12), Piatykhatky district of Dnipropetrovskyi Region (12), Oleksandria district of Kirovohrad Region (8) and in many other areas, there are a few people with that name. Of the more than eight hundred carriers of the surname Buta (Бута) most of all dwell in Transcarpathia and Bukovina, but also a lot in Western Ukraine – in Lviv (40), Radekhiv district of the Lviv Region (38), less in the eastern regions – in Kyiv (17), Dnipro (7). Of the other Hungarian surnames found far beyond the borders of Transcarpathia (Sumy, Donetsk, Lugansk regions), although in small numbers, one can note the following: Vitash (a total of 56 carriers), Habor (over a hundred), Kochish (35), Sokach (77), Feher (36), Fey (11), Fekete (29), Forkosh (64) and some others.

The most common surname of Chechen origin in Ukraine is Hapon (Гапон), it is worn by 2,770 people, most of all in Kiev (266 carriers), Kharkiv (144), Poltava (60), Chernihiv (42); its derivative Gaponenko (3670 carriers) is found in the same places (Kiev – 310, Kharkov – 175, Donetsk – 126, etc.) – Chech. gIōpan the genitive from gIap "outpost", which takes on the meaning of a relative adjective ("of outpost"). Other surnames of Chechen origin may be as follows:

Bertsan (Берстан), 16 carriers of this surname were recorded, eight each in Zaporozhye and in the town of Vradiivka of the Nikolaev region – Chech. bertsan Gen. from borts "millet", taking on the meaning of a relative adjective.

Borts (Борц), in Ukraine 16 carriers, namely in the cities of Kharkiv (5), Mariupol (3), Sumy (2) and in other settlements for 1-2 persons – Chech. borts "millet".

Bukar (Букар), 134 carrier, most of all in the cities of Kherson (13), Balakley, Kharkov region (13), and in the town of Troitske of Lehansk Region – Chech. bukara"hunchbacked, stooped." The abbreviation of the Chechen word is associated with the morphological features of the Ukrainian language.

Vezarko (Везарко), 18 carriers, most of all in the Semenovsky district of the Chernihiv Region. – Chech. vēzarg "lover, beloved".

Govras (Говрас), 122 carriers, most of all in Kiev (21), but not all of them are indigenous people, in the village of Vyazevok, Gorodishchensky district, Cherkasy Region (17) – Chech. fovrakhь "horseback" from govr "horse", obviously a derivative word had the meaning "rider".

Degan (Деган), 8 carriers, almost all residents of the village of Pismechevo, Solonyansky district, Dnipropetrovsk Region. (7) – Chech. degan "cordial".

Dzhima (Джима), 281, carriers, most of all in the cities of Bila Tserkva (79), Chernihiv (24), Zvenigorod district of Cherkasy region (18) – Chech. zhima "young".

Zaza (Заза), 25 carriers, most of all in the cities of Dnipro (5), Romny (24), Lviv, and Horlobka (3) – Chech. zaza "flower" (of flowering tree), "flourish".

Ken'a (Кеня), 227 carriers, most of all in Chernihiv Region (Snov district – 36, the city of Chernihivв -21, Horodnia district – 16), in the towns of Seredyna Buda (22) and Shostka (20) of Sumy Region – Chech kъēna "old man".

Nazha (Нажа), 59 most of all in the city of Cherkasy (12) – Chech. nazh "oak".

Other surnames of possible Chechen origin may be: Bukartyk (226), Bursa (504), Goma (437), Gotha (77), Cerlan (68), Kizya (48), Metza (17), Metzan (17), Mokha (59). This list will be continued as searches for Chechen surnames in Ukraine continue. All toponymy and anthropony data are put on Google My Map (see below).

These place names together with the decrypted above Chechen ones were placed on the Google map (see. below).

The map shows place names decrypted with the Chechen language or contain a root pechen or chechen (red signs). The territory of the Chernihiv principality is highlighted in orange. The blue color indicates the alleged territories of Levedia and Etelköz. The Red line marks the boundary of the settlements on the Pechenegs by data from A.M. Shcherbak (FEDOROV-DAVYDOV G.A. 1966: 140, Fig. 20).

Dark green signs indicate place names decrypted using the Hungarian language or having other traces of the Magyars.

A chain of black signs along the Seversky Donets River are the hillforts of the Saltovo-Mayaki culture.

Dots of light green color indicate the settlements in which surnames of Hungarian origin are found. Orange dots indicate places of dissemination of surnames of possible Chechen origin.

According to historical information, the Pechenegs settled Levedia, displacing the Hungarians who inhabited it. Here it is appropriate to mention the opinion of Konstantin Bagryanorodny about the relationship between the Pechenegs and the Magyars:

The tribe of the Turks, too, trembles greatly at and fears the said Pechenegs, because they have often been defeated by them and brought to the verge of complete annihilation. Therefore the Turks always look on the Pechenegs with dread and are held in check by them (CONSTANTINE PORPHYROGENITUS. 1967: 3).

It is logical to assume that the Pechenegs did not occupy that space where Hungarian place names have survived to our time. Their accumulation on the right bank of the Volga raises doubts that the Pechenegs, who came from beyond the Volga, as is commonly believed, did not primarily inhabit its right bank, forcing the Hungarians to move westward. In addition to general considerations about the periodic appearance of nomads from Asia, confidence in the Turkic ethnicity of the Pechenegs is reinforced by the decoding of this ethnonym on a Turkic basis – Turkic bečanag "brother-in-law" (FEDOROV-DAVYDOV G.A. 1966: 136, PRITSAK OMELIAN, 1970: 95). However, it is completely unclear how this word could arise in the Turkic languages, without having among them etymologically related. Most likely, the Chuvash name Pechenegs Piçenek was the basis of this Turkic word. This is a fairly common occurrence during exogamous marriages when the nationality of the brother-in-law is transferred to the term of kinship. The reverse phenomenon is unbelievable – to call an entire alien tribe by brothers-in-law illogical. An attempt to explain the ethnonym based on the languages of the Ugric group as “pine people” is also unconvincing (GOLUBOVSKIY P. 1884: 34). Suitable words are absent in the Hungarian language, and the involvement of the Khanty one is not entirely correct, especially since such an interpretation is phonetically faulty. All these circumstances give reason to believe that the Pechenegs did not move from the east, but from the south, that is, from the Ciscaucasia, being one of the Chechen tribes that left their ancestral home in the North Caucasus and, for various reasons, took a long trip from the Don to the Danube and further. Since the Chechens called themselves Nokhchi, they did not need to use a common, but alien, word for self-name.

In addition to the common name of the Pechenegs Constantine Porphyrogenitus uses the word kangar only for a part of their tribes. To decrypt such a name well suited Chech. qānō "an elder (of a kin)" and gāra "kin, clan", while they again are unsuccessfully searching an explanation for this word in the Turkic languages (FEDOROV-DAVYDOV G.A. 1966: 136). It is difficult to get out of the captivity of traditional ideas, but one should be guided by facts, not by an established opinion.

Currently, the Chechens are quite small people, but the history of their alleged ancestors is rich in dramatic events from ancient times to the present day. According to V.O. Kluchevskiy, there is in some editions of Russian chronicles evidence that the Kievan princes Askold and Dir "beat a lot of the Pechenegs" in 867. Therefore, he concludes that "the Petchenegs about half IX cent moved close to Kyiv cutting of the Middle Dnieper space from its the Black Sea and Caspian markets" (KLUCHEVSKIY V.O., 1956: 131). The role of the Pechenegs in the further history of Eastern Europe is highly appreciated:

About half of the IX century Pechenegs crossed the Danube. This event, ignored by all new historical writings, had tremendous significance in the history of mankind. It is almost as important in its consequences as the transition of the Visigoths across the Danube (VASILIEVSKI V.G., 1908: 7-8).

Anyway, the Pechenegs "for quite some time exerted enormous influence on the fate of Byzantium» (VASILIEV A.A. 1998: 396). Accordingly, you can find a lot of information about the Pechenegs in the Byzantine sources, in the same way as in Ruthenian annals. In particular, the are names of the Pecheneg khans and chiefs of lower rank, some of which, having no reliable deciphering by means of the Turkic languages, can be explained Chechen. However, some names have obviously Türkic character (Ildey, Kuchuk, Temir). This is not surprising, since the Pechenegs often acted in alliance with the Turkic tribes of the Uzes, Berendeys, etc .:

In these decades (40-60-ies of XI century – V.S.) it is impossible to determine exactly – what kind of nomads made their forays deep into Ugria or crowded the Byzantine frontier. Magyar sources mixed them calling as the Besses or Kunes, but Byzantine unite all them in the common classic name of Scythians. Sometimes, indeed, various nomadic tribes joined together to make any foray and so have made even more confusion in the terminology (RASOVSKIY D.A., 2012: 57)

Such attitude to the nomads was typical, Walter Pohl writes the same (POHL WALTER, 2002: 4). In addition, we can not exclude cases of borrowing personal names among the ruling tribal elite:

Let no one say that this name is quite foreign to the Gothic tongue, and let no one who is ignorant cavil at the fact that the tribes of men make use of many names, even as the Romans borrow from the Macedonians, the Greeks from the Romans, the Sarmatians from the Germans, and the Goths frequently from the Huns. (JORDANES, 1960, IX, 58).

With all this in mind, we take not too strictly the fact that only a few names of famous Pechenegs can be quite believable decrypted using the Chechen language. To those following can be assigned:

Batana, one of Pecheneg rulers – Chech. betan an adjective from bat "mouth", "face"; bettan "lunar".

Gosta, the name of a Khan of Pechenegs, the first mentioned in the sources – Chwch. kost "assignment". Perhaps this was not a Khan, but only warlord runding Khan's errand.

Kegen, a Khan, Tirakh's rival – Chech. qēgina "shining, flashing"

Kildar, Tirakh's father – Chech. gIeldar "weakening, fatigue". The name is not very suitable for a Khan, but it is necessary to analyze the context, if it is not a word for definition of an aging Tirakh's father Tirah.

Kuela, one of Pecheneg rulers – Chech. qulla "source, spring".

Kur'a, a Pecheneg Khan smashed the squad of Prince Svyatoslav in 972 – Chech. kura "proud, arrogant".

Metigay, a Khan, who was baptized by Prince Vladimir the Great– Chech. mettig "place", "case".

Tirakh, a Khan, in the service of the Byzantine at some time – Chech. tērakh "date, number".

Apparently, both toponymic and anthroponotic testify to the Chechen ethnicity of the Pechenegs. This assumption can be confirmed by further research as place names in the known places of the presence of the Pechenegs, and the possible matches between the Chechen language and the languages of other peoples inhabited Sarmatia. First of all, they need to be looked for in Hungarian and you can find them quite easily. Below is a list supplied by Chechen words that have matches found in the etymological dictionary of the Hungarian language (ZAICZ GÁBOR. 2006.), as an uncertain or unknown origin.

Chech. aьsta "a mattock", akhka "to dig" (aь – a front vowel) – Hung. ásó "a mattock".

Chech. baqō "right, law" – Hung. bakó "an executioner". Exact phonetic matching, although the semantics is remote, but an executioner administers justice.

Chech. berch "a wart" – Hung. bérc"a rock".

Chech. bēzam "simpathy", "love" – Hung. bezalom "trust".

Chech. boddan "to be worn out", "to lose cheerfulness" – Hung. bódít "to drug".

Chech. bog "a bump, lump, knar" – Hung. bog "knot", boglya "stack, rick".

Chech. borc "millet", burch "pepper" – Hung. borsó "pea", bors "black pepper" (maybe, all words from Cuv. пăрçа "pea").

Chech. borsh "bull-calf" – Hung. borjas "a cow with young" (from borjú "calf", borrowed from Chuv. păru "calf").

Chech. buьrka "a ball" (the ergative case – буьрканē) – Hung. burgonya "potatoes".

Chech. guьla "pack of dogs" – Hung. gulya "herd".

Chech. dac "no", "not is" – Hung. dac "obstinacy".

Chech. kert "fence", "yard" – Hung. kert "harden".

Chech. sākkhō "control, oversight, supervision" – Hung. szakács "cook".

Chech. khottar "connection" – Hung. hotár "border".

Chech. shayn "their" – Hung. sajat "own"

Chech. shach "sedge" – Hung. sás "sedge"

There may be other examples of Chechen-Hungarian lexical matches, but one should keep in mind that some of them may indicate contacts of the Khazar period or have a common source of borrowing. In addition to the above-mentioned Chuvash parallels, others can also be found that can also refer to Khazar times, but the links between the Chechen language and the languages of peoples whose contacts with Chechens are not witnessed in history will be of great significance. This is the subject of research by specialists, but such a lexical match has already been discovered: other-English tulge "strong" – Chechen. tIulg "stone". In addition to Old English, some language matches must be found in Romanian, Bulgarian, Greek. The undoubted connections of the Chechen language with the Ossetian can have a different explanation.

If we agree with the Chechen ethnicity Pechenegs, the question immediately arises whether only the Chechens were among many peoples of the North Caucasus, who left inhabited places and set out to find new ones. It remained in the annals information about the people who participated in the historic events in Eastern Europe together with the Pechenegs. This is primarily the Cumans, and then the so-called Chorni Klobuky ("black hoods") including the Berendei, Torki, Kovui, and others. Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos also named the Kawars or Kabars. He pointed out that the Kawars "derived from the genus of the Khazars", which can speak not about the origin but the place of their previous stay. Then they can be associated with modern Kabardinians, whose ancestors the Adyge, already took part in the campaigns of the Cimmerians in Asia Minor (see the section Cimmerians)

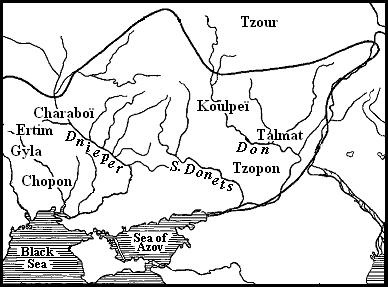

Constantine Porphyrogenitus notified that all the Pechenegs are divided into eight tribes: Ertim, Tzour, Gyla, Koulpeï, Haraboï, Talmat, Hopon, Tsopon (Chopon). Their hypothetical settlement by the data of A.M. Shcherbak is shown on the fragment of his map left.

More or less satisfactory, we can decipher by means of the Chechen language only some of them:

Tzour – Chech. chūra "inside".

Gyla – Chech. gyla "slabsided".

Hopon – Chech. gIōpan, genitive of gIap "outpost".

Tsopon – чеч. chopanan "foamy"

Such rulers stan at the head of these tribes: Baïtzas, Kouel, Kourkoutai, Ipsos, Kaïdoum, Kostas, Giazis, Batas. Their names also can not have good decoding. Obviously, other languages of the peoples of the North Caucasus, such as Turkic Dagestan and Abkhazian-Circassian should be involved in this.

Epigraphy Northern Black Sea coast may indicate that the Chechens remained among the Sarmatianі long before they became known in history as the Pechenegs. In the list of personal names of the Sarmatian time (ABAYEV V.I. 1979) about five percent of words can be deciphered only using the Chechen language, here are some of them::

Αρδοναστος (ardonastos), Tanais – Chech. ardan "to act", aьasta "hoe".

Γοργοσας (gorgosas), the father of Khakh (see Χαχας), Gorgippia – Chech. gorga „round”, āsa „belt, stipe”.

Θιαγαροσ (thiagaros), Midakhos' father (see. Μιδαχοσ), Tanaida – Chech. thæghara «the last, past»

Μιδαχοσ (midakhos), the inscription in Phanagoria, the son of Thiagar (see Θιαγαροσ) – Chech. mettakh, the derivative of mettig "place".

Οχοαρζανησ (okhoardzane:s), Tanaida – Chech. oьkhu "flying", æaьrzu «eagle», æaьrzun «eagle» (adj).

Παναυχος (panaukhos), the son of Ardar (see Αρδαροσ), Tanais, Latyshev – Chech. pāna "novel", ōkhu is the participle from ākha "to plow".

Πατεσ (pateis), Okhordzan' father (see Οχοαρζανησ), Tanaida – since the name of Okhordzan is well explained by the Chechen language, his father's name should also be of Chechen origin. In this case, you can keep in mind Chechnya. pott "tree block" in the oblique case with ending –e.

Στυρανοσ (sturanos), Gorgippia – the father of Midakh (see Μιδαχοσ), Phanagoria; Sozomon's father Gorgippia – Chech. steran – g. of stu «bull».

Χαχας, the son of Gorgos (see Γοργοσασ)- Chech. khēkhō "watchman", khьakha 1. "to languish," 2. "to doom".

The presence of Chechens in Sarmatia also has historical evidence. In the "Armenian Geography", which was apparently written by A. Shirakatsi, who collected data from Ptolemy, some Nakhchmatyans are mentioned (PATKANOV K.P. 1877). This name should be referred to the ancestors of modern Chechens, who call themselves Nokhchi, while Chech. mott means "language" and -yan is the Armenian suffix. This fact was not ignored by historians but was considered doubtful as the ancestors of the Chechens couldn't reside at the mouth of the Don River in the 7th cent. AD, because at that time they were supposed to inhabit modern Chechen-Ingushetia. (KRUPNOV E.I. 2008). However, taking into account the analysis of onomastics and other historical evidence, this fact has to be accepted.

The result of the history of the Pechenegs was their settlement of the Crimea, where they were forced out of the steppes by the Cumans starting in the middle of the 11th century. Finding a new living space was brutal:

… the Pechenegs destroyed all the Crimean steppe Bulgarish-Khazar settlements and, apparently, exterminated all the inhabitants who resisted them (PLETNEVA A.S. 1986, 67).

However, the traces of the Chechens in Crimea date back to the time of the Bosporan kingdom, as evidenced by the epigraphy of Panticapaeum. The similarity of the artifacts from the Gapon hoard to the Crimean ones has already been mentioned above. The following Crimean place names can be attributed to the new invasion of the Pechenegs:

Alupka (Алупка), a resort city in Crimea – Chech. ālu "flame, coals", pkhьa "settlement".

Alushta (Алушта), a city on the southern coast of Crimea – Chech. ālush is the genitive case of the word ālu "flame, coals", taIa "snuggle".

Artek (Артек), a tract on the banks of the river of the same name – Chech. aьrta "blunt", ekъa "stone plate".

Dzhankoy (Джанкой), a town in the north of Crimea – Chech. zhen is the genitive case of the word zha "flock", koy – plural of the word ka "ram".

Ishun' (Ишунь), a village in Crimea – Chech. yishin is the genitive case of the word yisha "sister".

Kacha (Кача), a river and an urban-type settlement in Crimea – Chech. kkhāchа “food”.

Kerch (Керч), a city on the Kerch Peninsula in the east of the Crimea – Chech. kkxerch “furnace”.

Koreiz (Кореїз), an urban-type settlement on the southern coast of Crimea – Chech. kkhorē is the locative case of kkhor "pear", yiz "pestle, beater".

Massandra (Массандра), an urban-type settlement in the Yalta Municipality in Crimea – Chech. massō “all”, andō “firmness”, -ra is the postposition “out”.

Hurzuf (Гурзуф), a resort town in Yalta Municipality – Chech. uьrsō is the ergative case of urs "knife".

Saky (Саки), a town, the center of the district in Crimea – Chech. sakkh "observant".

Simeiz (Сімeїз), an urban-type settlement on the southern coast of Crimea – Chech. sema "axis", yiz "pestle, beater".

Yalta (Ялта), a city on the Black Sea coast – Chech. yalta "crop".

After the settlement of the Crimea by the Cumans, the Pechenegs were assimilated by them, retaining their traces in the anthropological features of the Crimean Tatar population.

On the map of the Crimea, published in 1553 with Italian names, there is no trace of the toponyms discussed above (see below). However, at that time they should have already existed. Obviously, the map was compiled by the Genoese, who had their colonies in Crimea, but they were not interested in the names of the area used by the natives. Accordingly, as a historical document, the map has little value, although historians may not know this and use it with confidence in their work, an example of which is the contrived story of medieval New England [GREEN CAITLIN R. Dr/ 2015].

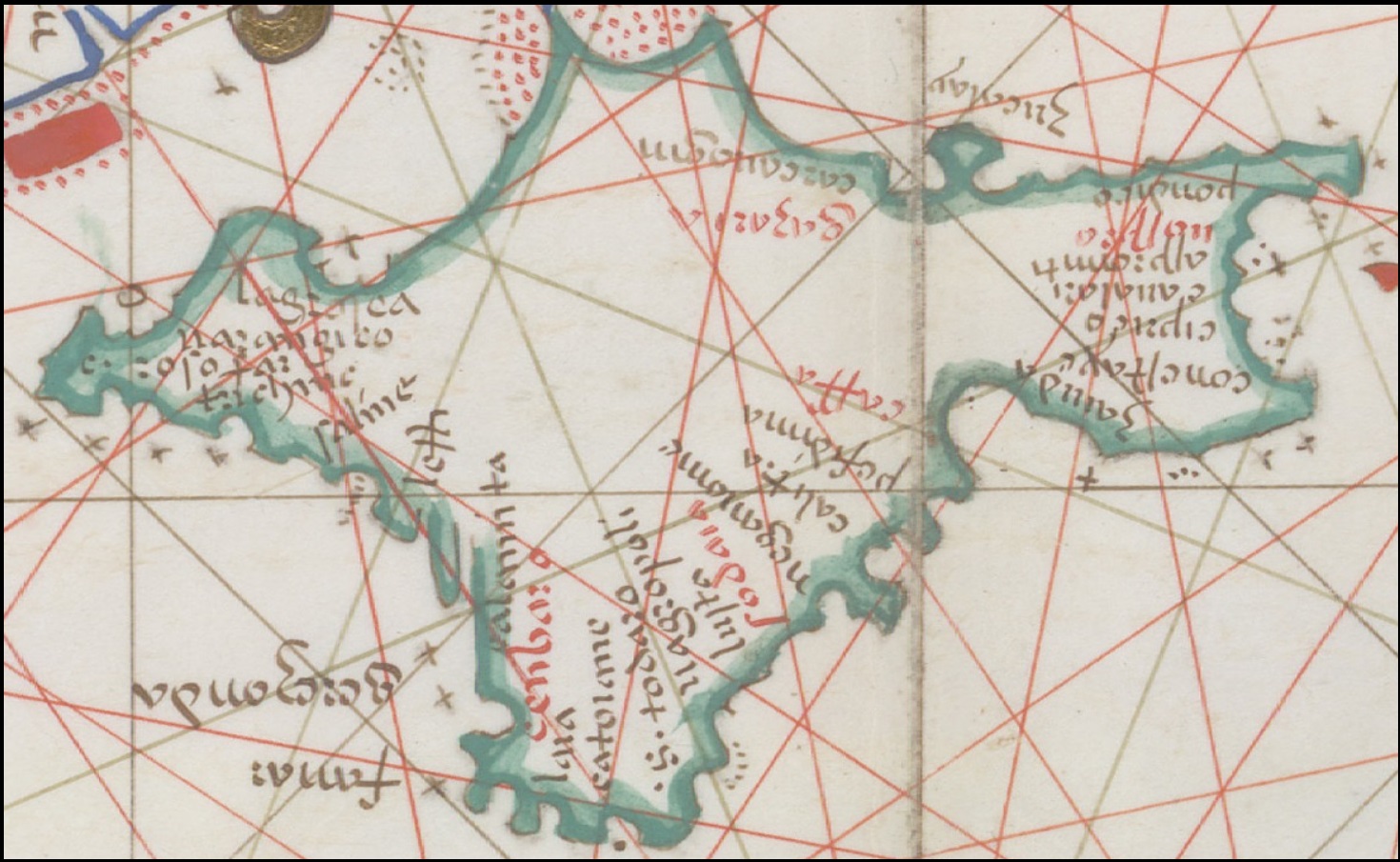

Extract from an Italian portolan atlas of 1553. (image: Wikimedia Commons).

Despite the fact that the Pechenegs in the middle of the 10th century occupied all the steppes of the Northern Black Sea region, their descendants over time disappeared among other peoples. It seems that this people has completely disappeared from the face of the earth. However, Konstantin Bagryanogordny also reported about its presence in his ancestral home:

At the time when the Pechenegs were expelled from their country, some of them of their own will and personal decision stayed behind there and united with the so-called Uzes. and even to this day, they live among them (CONSTANTINE PURPHYROGENITUS. 196: 37).

The Turkic Uze tribe should be understood as modern Kumyks, who were and are still neighbors of the Chechens (see map below). Therefore, the history of the Pechenegs is not over yet.

Right: Ethno-Linguistic map of Dagestan at the middle of the 20 cen.

The Kartvelian languages 1. Georgian

The Nakh languages

7. Chechen 8. Ingush 9. Kisti 10. Batsbi

The Dagestan languages

11. Avar 12. Lak 13. Dargwa 14. Tabasaran 15. Lesgi 16. Aguli 17. Rytul 18. Tsakhur 19. Khinalugi 20. Kriz 21. Budukh 22. Udi

The Turkic languages

34. Azerbaijan 35. Karachay 36. Balkar 37. Kumyk 38. Nogai 39. Turkmen 40. Tatar 41. Kazakh

The Indo-European languages 23. Russian 24. Ukrainian 25. Armenian 26. Ossetic 27. Kurdish 28. Talishi 29. Tatish 30. Jewish-Tatish 31. Greek 32. German 33. Romanian