Far East: The Relationship of the Altaic and Turkic Languages.

The seeming self-evidence of the Altaic ancestral home of the Turkic people logically led to the idea of the genetic relationship of the Mongoliс and Turkic languages. Still, the facts contradicting this doctrine gave rise to many years of debate by specialists:

This problem, like many others, currently results in a dispute between whole generations of scientists, neither of which can convince the other. Apart from the deceased scientists, the main supporters of the theory in question are such older scientists as Prof. N. Loppe (Washington University) and Prof. K. Menges (Columbia University), who devoted their entire lives to the study of these languages; opponents of this theory are mostly young scientists, for example, G. Doerfer and A. M. Shcherbak (Leningrad) (CLAUSON G. 1969: 22).

About 50 years have passed since the time of writing these lines, but the situation has not changed; the number of supporters of the Altaic theory has not diminished. In general, in their approach to solving the problem of the origin of the Turkic people, Asian scientists often note the prejudiced attitude of European ones, especially Russian scientists, for the most part following the state policy:

The Russian Empire, to force the Turkic peoples to forget their past, obliged Russian scientists (and not only Russians) to falsify the ethnic and political history of the Turkic peoples. As a result of this, the so-called "Altai hypothesis" of the origin of the Turkic people was created. Especially stubbornly and aggressively, this "hypothesis concept" was introduced into academic science during the years of Soviet power. Any deviation from this "concept" was severely punished. Many scientists who did not agree with it were repressed (GUMBATOV GAKHRAMAN. 2012: 4).

These words belong to an Azerbaijani independent researcher who, in an independent state, can afford the courage to express his thoughts frankly. In Russia, Turkic-speaking scholars are more diplomatic in their expressions. In particular, the work of the Balkar Turkologists about such a feature of the state policy of Russia can be read between the lines:

The origin of the Türkic peoples and their ethnocultural traditions is one of the least studied problems of science. Its undevelopedness is due not so much to the weakness of the scientific base but to the biased attitude of many scientists, especially the Iranianists, towards it. The Indo-Europeanists dictated and continue to dictate to the Turkologists the ways and methods of studying ethnogenesis and other problems of the history and linguistics of the Türkic peoples. At the same time, some of them deliberately distort, and sometimes simply ignore, their historical and cultural wealth (LAYPANOV K.T., MIZIEV I.M. 2010: 4).

Indeed, well-known Turkologists, first of all, Z. Gombocz, G.I. Ramstedt, N.N. Poppe, N.A. Baskakov, S.A. Starostin, J. Benzing, M. Räsänen, L. Ligeti did not doubt the genetic relationship between the Turkic and Mongolic languages and proved it by comparative-historical methods. However, the reproach of Balkar scientists is not entirely fair. There was another approach to solving the Altai problem, based on a historical-typological comparison. The founder of this direction, called Neo-Altaistic, was V.L. Kotvich (ANDREYEV N.D., SUNIK O.P. 1982: 26). This direction was joined by K. Grǿnbech and J. R. Krueger, but in general, the attitude to their outlook was skeptical. Sir G. Clauson stands in their defense. Based on the analysis of the ancient Turkic and Mongolic texts, he came to the conclusion that they practically have no common vocabulary, except for international words such as kagan "supreme ruler" and teŋri "heaven" (CLAUSOΝ GERARD, 1956: 182). Later, Sir Gerard dealt with this issue in more detail and came to the following conclusion:

It has been suggested that the Turkish, Mongolic, and Tungus-Manchu languages form such a family, commonly called the Altaic and that they are all descended from a lost primeval language called Altaic or Proto-Altaic. For some years now I have been coming more and more to the opinion that this is an error and that the fact that these languages have a good deal of vocabulary material in common is best explained, not by assuming that they have inherited it from a common ancestor, but by assuming that a prolonged and complicated process of exchanges has taken place between these languages… I am quite convinced that Turkish is not genetically related to either of them. (CLAUSON GERARD, 2002: 21-22).

It should be added to Clawson's words that Altaists also include Japanese and Korean languages in the Altaic family, the written monuments of which "contain a significant number of common Altai words" (SYROMIATNIKOV N.A. 1975: 60), but they do this is not entirely certain, admitting that "the Eastern branch of Altaic – Korean and Japanese, or Korean-Japanese – was brought under heavy suspicion", noting the active search for relatives of the Japanese language in a completely different direction by reputable linguists (STAROSTIN S.A., DYBO A.V., MUDRAK O.A. 2003: 8) In general, Altaists try to transfer the dispute about the genetic relationship of the Altaic languages to another plane:

Although the arguments of anti-Altaicists were many – from phonetic to lexico-statistical – their basic argument can be summed up as follows: the relationship between the Altaic languages is not what a genuine genetic relationship should be. All the numerous resemblances between them were explained as a result of secondary convergence within a “Sprachbund” of originally unrelated languages. The whole idea of the original Proto-Altaic unity was very seriously threatened (ibid: 8).

Attention should be paid to a significant methodological error in the studies of Altaists, which causes bewilderment. It is known that "the application of the comparative-historical method is possible only in relation to genetically related languages" (ANDREYEV N.D., SUNIK O.P. 1982: 26). However, this method still applies. For example, in the work cited above, the relationship of languages is first postulated, then they contain common grammatical morphemes were found, which "prove the proximity of languages even more than common lexemes" (SYROMIATNIKOV N.A., 1975, 60). The proof must not make a circle. Other methods are needed to solve the problem of the relationship between the Altaic languages. One of them can be graph-analytical method.

Using this method, we found the ancestral home in the Transcaucasia (see The Urheimat of the Nostratic Languages) and then localized the habitats of Türkic tribes speaking distinct dialects originated from the common parent Türkic language in East Europe (see The Türkic Tribes). In this case, the Mongolic languages can be related genetically to Turkic only if they were formed in the vicinity surrounding area. Let us try to establish whether this was so.

Sergey Starostin compiled a large database on the Altaic languages (The Tower of Babel), and this is presented in the Internet in a form that allows one to apply the graphic-analytical method to justify kinship (see below).

At left: The graphic model of the general relationship of the Altaic languages

As you can see, the Türkic languages fit quite well into the constructed model, but, as it was determined previously, they take one of the central places in the relationship model of Nostratic languages, which corresponds to an area in Asia Minor. In this case, we have to determine if the other Altaic languages belong to Nostratic or not. To resolve this issue we need to find terrain for a graphical model of the Altai languages on which their parent languages could have arisen. The graph can be placed in different places in Europe and Asia since it only has five knots. To facilitate the search for an exact place, we first have to build models of the relationship of the Mongolic and Tungus-Manchu languages to find a more confident place on a geographical map with available ethno-producing areas where these languages could arise.

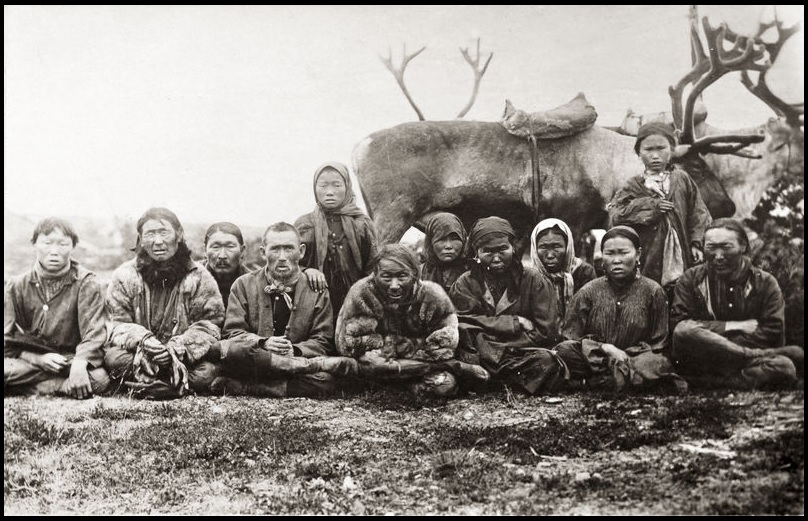

Evenks

Photo from Slovesnitsa iskusstw

After obtaining such a binding to a particular locality, it will be easier to establish the places where the other Altai languages were formed. Let's start with building a model of the Tungus-Manchursky, data for which can be taken from the Database compiled by Anna Dybo. There are in the Database 2294 Proto-Tungus-Manchu roots for which are given matches of 11 following languages: Evenki, Nanai, Manchurian, Even, Negidal, Ulchi, Orok, Oroch, Udighe, Solon, and Jurchen. All these languages have 134 common roots, which have matches at least ten languages. They were eliminated from the analysis of kinship of the Tungus-Manchu languages by the graphical-analytical method. For the rest of the roots, the numbers of mutual words in each pair of these languages were calculated. These data are shown in the table below. Also, data on the distances (in centimeters) between the points of the set of individual languages are submitted for convenience. These data were used to build a relationship model with a proportionality factor of 3500. In the table, the main diagonal shows the total number of words for each language. The words of the Solon language turned out to be too few to reliably include in the scheme of kinship, although its place would certainly have to be in the far west in accordance with the number of common words with the rest of the Manchu-Tungus languages. About the place of the dead Jurchen language among the Tungus-Manchu according to the table, it is impossible to speak.

Quantuty of mutual words between the individual Tungus-Manchu languages

| Evenk | Nanai | Manch | Even | Negid | Ulcha | Orok | Oroch | Udighe | Solon | Jurch | |

| Evenk | 1431 | 4,4 | 5,4 | 3,8 | 4,2 | 5,6 | 5,5 | 6,7 | 6,5 | 12,6 | - |

| Nanai | 791 | 1218 | 5,4 | 5,8 | 48 | 59 | 5,2 | 6,0 | 6,2 | 15.8 | - |

| Manchur | 642 | 649 | 1064 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 20.1 | - |

| Even | 916 | 601 | 478 | 1063 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 14.8 | - |

| Negidal | 838 | 726 | 492 | 684 | 1022 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 13.8 | - |

| Ulcha | 623 | 638 | 492 | 478 | 621 | 936 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 17.9 | - |

| Oroki | 630 | 671 | 435 | 520 | 610 | 621 | 857 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 17.7 | - |

| Orochi | 519 | 585 | 388 | 415 | 529 | 523 | 470 | 721 | 7.6 | 19.1 | - |

| Udighe | 542 | 558 | 393 | 428 | 512 | 468 | 432 | 460 | 713 | 21.9 | |

| Solon | 277 | 221 | 174 | 237 | 254 | 195 | 198 | 183 | 160 | 320 | |

| Jurchen | 97 | 117 | 158 | 71 | 84 | 91 | 75 | 72 | 65 | 46 | 170 |

Based on this table, the graphic model showing kinship of Tungus-Manchu languages was built (see below).

At right: The graphic model of the relationship of the Tungus-Manchu languages

The selection of one of the two possible mirror variants of the model and its orientation is determined by the actual residence of the speakers of the Manchu and Evenki languages. The Manchus, the most numerous people of the family, dwell now in North-East China, that is, south of the rest of the kindred peoples. The second-largest nation, the Evenki currently populate the vast area from the Yenisei River to the Okhotsk Sea with the southern limit along the Amur and Angara Rivers. Their small settlements are also located in Mongolia and China, but in general, Evenki migrated westward. The residence of other Tungus-Manchu peoples largely corresponds to the model. This correspondence can be found on the map showing the small groups of people of the Khabarovsk Region and Sakhalin Island (see below). The map was compiled according to different sources, such as the national contingent of administrative units of the Region and the settlement of the bulk of the small peoples. If you do not take into account the migration of some people from their ancestral home, the correspondence is obvious.

At left: The map of actual habitats of the small peoples in the Khabarovsk Region and Sakhalin Island. The map shows the main places of settlements in large font and the sporadic ones in smaller font.

Let us consider more details. The ancestors of the Evens followed the Evenkis, the bulk of which reside in central Siberia now, but a small part of them remained near their ancestral home. The ancient speakers of the Solon language, whose area had to be somewhere in the west of the common territory of the Tungus-Manchu, went just to the west and now dwell in Mongolia.

The actual space of the Udeghes contradicts the model (their position on the model is defined in the far north) as now they reside in the south of the Khabarovsk Region. However, the Orochi, the Ulchi, the Negidals, and the Nanai kept their settlements near their ancestral home. In this case, we must assume that the Udeghes had to move to the south, bypassing the settlements of the Negidals and Nanai. Sakhalin logically had to be settled by the Orochis, but this was done by the Orokis, who had to pass the Orochi settlements.

The search for the Tungus-Manchu ancestral home by other linguistic methods leads to a territory close to the one that was determined by the graphical-analytical method:

… the vocabulary of the Tungus-Manch languages (the names of some leafy trees, salmon, as well as the names of rivers) gives reason to include the Middle Amur basin in the area of the Tungus-Manchu ancestral home (country of linguistic ancestors) (PEVNOV A.M.. 2008, 67).

However, the location of the areas that formed the individual Tugnus-Manchu languages by purely linguistic methods is impossible.

Now, we turn to the construction of a graphic model of Mongolic languages. It was built using using the Database, compiled by Oleg Mudrak. He gave data on the following languages: Mongolian writing, Middle-Mongolian, Khalkha, Buryat, Kalmuk, Ordos, Dungxian, Baoan, Dagur, Shary-Youghur, Mongour, and Mughal. The place of the proper Mongolian language in the graphic model is determined by the Khalkha language. Accordingly, the data of the written Mongolian, Middle Mongolian, and Mughal were not taken into account. The entire set of data was tabulated (see the table below).

Quantuty of common words between the individual Mongolic languages

| Khalkha | Buriat | Kalmuk | Ordos | Dagur | Mongour | Shary-Yg | Dungxian | Baoan | |

| Kalkha | 1540 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Buriat | 1297 | 1319 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kalmuk | 1287 | 1297 | 1308 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ordos | 1051 | 942 | 964 | 1062 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dagur | 561 | 538 | 531 | 486 | 585 | - | - | - | - |

| Mongour | 472 | 435 | 430 | 402 | 301 | 492 | - | - | - |

| Shary-Ygoughur | 329 | 317 | 318 | 306 | 253 | 202 | 342 | - | - |

| Dungx | 178 | 167 | 168 | 164 | 113 | 140 | 83 | 179 | - |

| Baoan | 119 | 112 | 114 | 90 | 82 | 92 | 61 | 67 | 121 |

Due to the insufficient number of words in the database for the Dungxian and Baoan languages, they cannot be included in the model (see it at right).

At right: The graphic models showing the relationship of the Mongolic languages

The experience of the research of different language families and groups using the graphical method allows us to assert that high-density clusters on the graphical model often display not only the proximity of language areas but also a greater quantity of documented words in these languages compared to others. This phenomenon was taken into consideration when searching for a suitable place for placing the obtained model on a geographic map. Having the graphic model of the kinship of the Altaic languages and the found territory of the Tungus-Manchurian, we can determine the place for the Mongolic languages in the basin of the right tributaries of the Amur River. The supposed areas of the Dungxian and Baoan languages were located from general considerations (from modern settlements and the proximity to other Mongolic languages).

Thus, we come to the obvious conclusion that the entire territory on which the formation of the Altai languages took place should be located in the Amur basin and in the adjacent territory (see the map below).

At left: The areas of origin for the Mongolic, Tungus-Manchu, Korean, and Japanese languages.

According to the model of relationship, the Korean language (the most remote from the rest of the Altaic) was formed on the peripheral area, i.e., the Korean peninsula. That the Koreans populate this territory at present it is an additional fact in favor of the correctness of the location indicated by the graph. The ancestors of the modern Japanese dwelled in the territory of Primorye, well limited by the Ussuri River, Amur, and the shore of the Sea of Japan. From there they moved to the Japanese island trough Sakhalin, either directly on the frozen sea.

The peoples of the Far East, being on the outskirts of the civilized world, for a long time maintained their existence by hunting, fishing, and gathering, i.e. were still at a rather low level of social development. The common culture and languages of the local population corresponded to this level. Structural changes in the economy of the Amur region begin with a gradual transition to product management. The data of archeology display the appearance of "agricultural features" in this region roughly since the end of the III and beginning of the II millennium B.C. (BROMLEY Yu.V., 1986: 257). There is evidence that the development of agriculture is associated with the penetration here of tribes from Central Asia and Southern Siberia.

Buryats

Photo from Irkipedia

Following the graphical model of the kinship of the Altai languages, the territory inhabited by the Turkic tribes was supposed to be in Transbaikalia, being limited in the east by the Argun River, beyond which the region of the Mongolic tribes was already beginning. Thus, we can assume that at the beginning of the third millennium BC, some Turkic tribes left their ancestral homeland in the interfluve of the Dnieper and the Don Rivers and moved eastward; some part of them reached Altai and further (see The First Great Migration). Here they met a population of Mongoloid anthropological type that spoke Mongolic dialects as a whole less developed and poorer in comparison with the languages of the newcomers-Turkic people, who stood at a higher level of cultural development. The consequence was a massive infiltration of the Turkic lexical and grammatical forms in the language's closest neighbors – the Mongols and Tungus-Manchus- and from these languages into languages of more eastern ethnic groups.

But there was also a reverse process of penetration of local vocabulary into the Turkic languages, which is connected with the peculiarities of the natural conditions of this territory, new for the Turkic tribes. Over time, the languages of this region acquired features of similarity so abundant that they left no doubt about their genetic relationship. Nevertheless, an in-depth study of the structure of languages attributed to the Altai gave grounds for the problem of their relationship in another way:

It is known that similarities found in different languages are not necessarily a consequence of their genetic relationship. Often, the convergence of languages, regardless of the nature of the initial connections between them, is due to their interpenetration, the degree and extent of which depend on various circumstances and, above all, on the duration and intensity of contacts. The interaction of the Turkic, Mongolian, and Tungus-Manchu languages occurred continuously for many centuries, and there were periods when it became stable and unusually intense (SHCHERBAK. 1966: 36-37).

A.M. Shcherbak wrote about centuries of interaction and such a period, perhaps, could not have significantly influenced the acquisition of similarity of languages, but in reality the interaction continued for several millennia. The closest contacts with the speakers of the Altai languages (who, however, were never in Altai) should have been primarily the Yakuts and then the Tuvans, Kyrgyz, and Khakass, who occupied the eastern areas of their historical ancestral homeland. The Yakuts, even now, occupy the most eastern territories of all the Turkic peoples. There is no doubt that there was an intensive miscegenation of the newcomers with the local population, as a result of which the Turks who arrived here acquired pronounced Mongoloid features.

View The Mongolic and Tungus languages in a larger map

We have strongly rejected the genetic relationship of the Turkic languages with Mongolic and Tungus-Manchu and further evidence of this statement is presented separately in the section Discussion. However, for the reader's convenience, we will briefly repeat them here.

The main proof of the absence of a relationship between the Turkic languages and the rest of the Altaic is the formation of individual proto-languages, which are considered to belong to Altaic, has been occurring in different places. The Urheimat of the Turkic people (determined by using the graph-analytical method) was in Asia Minor and not on the Altai, as it is commonly believed (see розділ The Urheimat of the Nostratic Languages).

The kinship of the Turkic and Mongolic languages is contradicted by the absence of sufficient counterparts between the words that can be considered the most ancient, most of which are usually the most commonly used in speech. They constitute the main lexical core of a language. At one time, the American scientist Morris Swadesh tried to compile a list of the lexical nucleus that should be present in all languages and that, in his opinion, decomposes with the loss of individual words at a constant speed. Swadesh included in the list a hundred words but later expanded it to two hundred (SWADESH M. 1960-1, 1960-2). If we compare these lists of restored Mongolic and Turkic paternal languages, it turns out that they have almost nothing in common, except for some pronouns that may arise even in a human proto-language, the names for men and heart, and three colors (black, yellow and green/blue), clearly borrowed from Turkic. Experts can add to these words two or three more, but for the hundred words of the lexical nucleus, this is very few, because it didn't decay so quickly in any language.

Many other linguistic facts are also contrary to the Asian origin of the Turkic people, but one looks for a far-fetched explanation for them. For example, Sir Gerard Clauson, considered the common Türkic name of cannabis kendir, wrote: "Unlikely to have been an indigenous plant in the area originally occupied by the Turkic people and probably an Indo-European (?Tokharian) l.-w." (CLAUSON SIR GERARD, 1972). It is a strange thought as the word is widespread in the Türkic languages and is completely absent in Indo-European languages.

Sir Gerard Clauson brings up another interesting fact. He believed that Latin. virga "a branch, twig" has no match in other Indo-European languages but gave Turkic ones – OT. bergä "a rod, whip", Uighur. berge "a whip, stick". He wrote:

It is suggested.., that it is a loan word from Latin virga ‘a rod, a stock’ obtained through Middle Persian but there does not visible to be any trace of the word in Persian, and the theory is imponderable. Ibid.

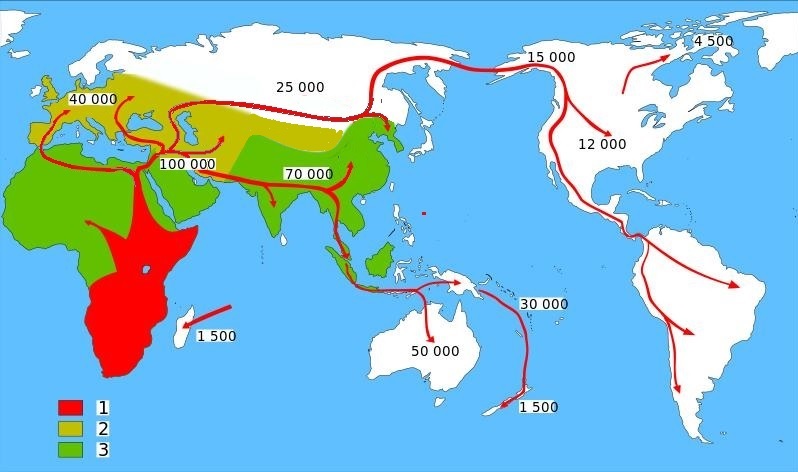

In favor of the Asiatic origin of the Turkic people, many borrowings from the Chinese language could be said, but the phonetics, morphology, and syntax of these languages are so different that there is no reason to speak of their kinship. Moreover, the Chinese and other Altai languages also have no kinship. This is because their formation occurred in different places, and their speakers migrated to Asia at different times (see the map below)

Left: Spreading homo sapiens.

1. Homo sapiens sapiens.

2. Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

3. Early Hominids.

The map on the left shows that the Amur River basin was inhabited by modern humans about 20 thousand years ago, ie, before the speakers of the Sino-Tibetan languages have penetrated into China (see the sec The Relationship of the Sino-Tibetan languages). This explains the fact that the Sino-Tibetan languages, on the one hand, and the Mongolic and Tungus-Manchu, on the other hand, have no genetic relationship.

Searching for a connection of the last should be carried out, where they came from, that is, in the Mediterranean region. Minoan and Japanese have certain similarities in the sound structure that are considered strange, and therefore the assumption that there is a relationship between the Japanese and ancient Cretans seems impossible due to geographical remoteness and so this possibility is excluded (SHEVEROSHKIN V.V., 1968 310). Perhaps a more careful examination of the structure of the Tungus-Manchu and Minoan languages will help to find the truth.

As a result of the short consideration of the problem of Turkic-Mongolian relations made here, we can draw the following conclusion, made in the thorough work of an inquisitive researcher after studying historical documents, cultural-linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographic evidence:

- the hypothesis that Altai is the ancestral home of all modern Turkic peoples and that it was here that the language of the ancient Turkic people was originally formed cannot be accepted;

- the historical ancestral home of the ancient Turkic people is the South Caucasus. The ancient Turkic people in the 6th millennium BC, having mastered distant pastoralism, over the next 2 millennia did not leave their ancestral home – the southwestern coast of the Caspian Sea. Then, when the Turkic community increased numerically, some of them, in search of new pastures, moved northward along the western coast of the Caspian Sea. At the end of the third millennium BC. in their lives, there was a sharp turn, which was associated with the domestication of the horse and the invention of the iron. Having experience in taming wild animals, the ancient Turkic people were able to domesticate a wild horse – tarpan. And soon, with the development of iron production, a period of more intensive development of the Eurasian steppe, which until then had practically not been populated, began. In the next millennium, the entire Eurasian Steppe from the Danube to the Yenisei was inhabited by steppe pastoralists (GUMBATOV GAKHRAMAN. 2012, 237-238).

Undoubtedly, the picture drawn needs to be clarified in detail, which offers a new way to restore the history of the Turkic people.