Volga Bulgars

Since the time of N.I. Ashmarin (1870-1933), the most widespread idea about the Bulgars' ethnicity is the Chuvash-Bulgar genetic relationship. This Russian Turkologist devoted his entire life to studying the culture and language of the Chuvash. His painstaking work resulted in the 17-volume "Dictionary of the Chuvash Language" based on materials collected according to the program he created for studying Chuvash folklore. Ashmarin was particularly interested in the origin of the Chuvashes and their attitude toward the Volga Bulgars, about whom there was no definite opinion in science at that time:

The question of the origin and language of the Volga Bulgars, as is known, still cannot be considered finally exhausted, although its proper resolution is of great importance for the historical and ethnographic study of the Volga region [ASHMARIN N.I. 1902: 2].

Ashmarin resolved this issue for himself unambiguously and the Bulgaro-Chuvash concept is developing in the direction he defined. This concept has numerous opponents who select arguments to explain the known linguistic and historical data in their own way. I undertake to reconcile the contradictory views using the results of my research and the toponymy of Volga Bulgaria.

The Bulgar tribes came to the Middle Volga region in the middle of the 7th century and occupied the territory from the Samara Bend to the mouth of the Kama. Later, other related tribes came to the Middle Volga region. The Bulgars gained the upper hand at the beginning of the 10th century. The father of their leader Almush Shilka bore the title of Elteber. Their names are associated with the spread of Islam among the Bulgars even before the arrival of Ibn Fadlan in Volga Bulgaria. Presumably, the first preachers of the Muslim faith appeared in this region in the 8th-9th centuries (PILIPCHUK Ya.V. 2020: 59). This raises the question: If the modern Chuvash are descendants of the Bulgars, then why aren’t they Muslims?

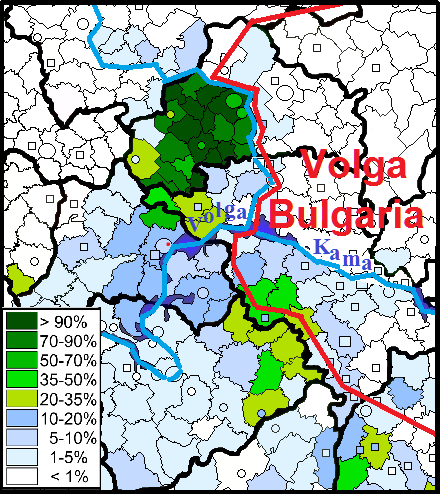

Currently, the Chuvashes dwell mainly on the right bank of the Volga, while the greater part of Bulgaria was located on the left bank up to the Urals (see Fig. 1). This raises the second question.

Fig. 1. The area of settlement of the Chuvash in the Volga-Ural region. (According to the All-Russian Population Census of 2010).

The third question is more complex. The Chuvash language stands apart from the Turkic languages and its great difference must have an explanation. There is none. If the Bulgars had come from beyond the Volga, they should have dwelled in the neighborhoods of other Turkic tribes in close language contact, which would not have allowed the Bulgarish language to differ sharply. Lexical correspondences between the Chuvash and Mongolian languages are cited as evidence of the Asian origin of the Bulgars. However, the Chuvash language has many more correspondences with German, which many researchers have noted, but the reason for this phenomenon is absent. All these issues are considered in more detail in the section Discussion.

In this narration, we proceed from the fact that the Chuvash are descendants of the Scythians, who came to the Black Sea steppes from Western Ukraine. There, on the territory of Upper Transnistria in the 3rd century BC, lived the population of the Corded Ware culture (CWC), which left behind monuments in the form of burials and settlements. Settlements arose already at an early stage of the development of this culture, but their number increased at a late stage (VOYTOVYCH MARIA. 2022: 32, 49). The creators of the CWC were part of the ancient Turks who moved from their previous places of settlement to the right bank of the Dnieper in search of additional pastures for grazing large herds of cattle and horses (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998, 66-67). The only descendants of these Turks who have survived to this day are the modern Chuvash, and their language has preserved the features of the Turkic proto-language more than other Turkic languages. During the migration process their ancestors stopped in Western Ukraine and dwelt close to the Teutons, the ancestors of modern Germans, whose ancestral homeland was in Volyn. This proximity explains the Chuvashe-German lexical correspondences. At the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, a significant part of these Turks began to migrate to the east and populated the Northern Black Sea region, where they became known in history as the Scythians (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2000, 18-32). In Donbas, the Scythian-Bulgars lived intermingled with the ancient Anglo-Saxons (see Royal Scythia and its Capital). Fleeing the Hunnic invasion, both migrated to the Middle Volga region. The territory of the settlement of the Anglo-Saxons is determined by the toponyms that have survived to this day and can be deciphered using Old English. Moreover, many of these toponyms were found from the Volga to the Urals on the territory of Volga Bulgaria. They were added to Google My Maps (see below).

Below is an explanation of the place names using Old English:

Abalak (Абалак) – OE abal "rower, force", āc "oak, a ship made of oak wood".

Almetyevsk (Альметьевск) – OE eall "every, entire", mete "food, nourishment".

Armizonskoye (Армизонское)– OE earm "poor", sunu 'son".

Asha (Аша) - OE asca, asce "ashes".

Atrach (Атрачи) - OE ātor, ætrig "poison".

Baykalovo (Байкалово-3) - OE. wealca "wave", eall "every, entire".

Biayanka (Биянка) - OE bean, bien "bean".

Boldino (Болдино) - OE bold "house".

Boldyrevo (Болдырево) – OE bold "house", ear 1. "earth", 2. "lake"

Bol’shaya Riga Большая Рига) - OE ryge "rye".

Burkovo (Бурково), absent on the map, Yusvinsky District. – OE burg "borough".

Chertovo (Чертово) - OE ceart "wasteland, wild public land".

Chertushkin (Чертушкино) - OE ceart "wasteland, wild public land".

Chetkarino (Четкарино) - OE ciete "closet, cabin", carr "rock".

Chita (Чита) - OE ciete "closet, kabin".

Churilovo (Чурилово) - OE ceorl "man, peasant, husband" (Eng churl)

Staroe Churylino (Старое Чурилино} - OE ceorl "a man, peasant, husband" (Eng churl)

Chuvaki (Чуваки) - OE ceowan "chew".

Debiosi (Дебьоси) - OE diepe, diepu "deep' , sǣ "lake, swamp".

Falino (Фалино) - OE fala, fela "many", "very".

Falyonki (Фаленки) - OE feallan "fall".

Firsovo (Фирсово – 2) - OE fyrs "furze, gorse, bramble".

Gamovo (Гамово) - OE gamen "joy, game".

Ingaly (Ингалы) - OE Ing "the name of a god", āl "fire".

Kartovo (Картово) - OE ceart "wasteland, wild public land".

Kharino (Харино) - OE hara "hare"

Kromy (Кромы) - OE cruma "crumb, piece".

Kukmor (Кукмор) - OE cuc (cwic) "lively", mor "moor, heath, desert".

Kultayevo (Култаево) - OE colt "colt".

Kurlovo (Курлово) - OE ceorl "man, peasant, husband" (Eng churl)

Leushino (Леушино) - OE leosca "strip", "switch".

Leushkanovo (Леушканово} - OE leosc "strip".

Liuga (Люга – 3) - OE leogan "lie", -loga "liar".

Malmyzh (Малмыж) - Sand island: OE mealm-stān "sandstone" (Goth malma "sand"), ieg "island". Sand island

Markova (Маркова – 4) - OE mearc "border, end, district", "sign"; mearca "determined space".

Puksinka – Пуксинка – OE fox "a fox", inca "grief", "quarrel", "suspicion".

Romodan (Ромодан) - OE rūma „space”, dān „humid, humid place”

Ryazanovo (Рязаново – 4) - OE 1. rāsian "explore, investigate". 2. racian "rule, lead".

Selty (Селты) - OE sealt "salt".

Shadrino (Шадрино -3) - OE 1. *sceader out of scead "shade, shelter, defense". 2. sceard "mutilated, crippled; plundered".

Shadrinsk (Шадринск) - see Shadrivo.

Sibirka (Сибирка) – OE sibb "relative", -er is a suffix.

Sim (Сим} - OE sima "band, rope".

Siumsi (Сюмси) - OE sioman "rest", sǣ "lake, swamp"

Shtanigurt (Штанигурт) – OE stān "stone", grūt "groats", "spent grain".

Tagil, Upper and Low (Тагил -2) - OE tægel "tail".

Tan (Тан -3) - OE tān "twig, branch"

Tsip’a (Ципья) - OE ciepa "trader".

Tumen (Тюмень) - OE Tīw, Germanic god of war, mǣnan "mean", "join".

Turnaeva (Турнаева) – OE turnian "turn".

Ufa (Уфа) - OE ūf "horn-owl, kite', Uffa – personal name.

Uva (Ува) - OE ūf "horn-owl, kite', Uffa – personal name.

Vagina (Вагина) - OE wagian "to move, shake".

Viktorovka (Викторовка) - OE wīċ ”dwelling, settlement”, Þūr/Þōr ”God of Thunder”.

Vogany (Воганы), the village is non-exitent – OE wogian "to wwo", "to merry"

Volpa, Upper and Low (Волпа) – OE wulf "wolf"

Vyatka (Вятка, Киров – 2) - OE wæt "humid, moist, -gê "gau, a district".

Yalutorovsk (Ялуторовск) – OE ealu(t) "beer", ōra "riverbank"

Yeltsovo (Ельцово) - OE ealh "temple"

Yurla (Юрла) - OE eorl -"noble man, warrior", earl.

Zengino (Зенгино) – OE sengan to "burn, to set on fire".

The most dense concentration of Anglo-Saxon toponymy is in the Republic of Tatarstan. The Balanovo culture was widespread here as one of the variants of the Corded Ware cultures. Its creator was one of the Turkic tribes that came here from the Azov region at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC (see Türks as Carriers of the Corded Ware Cultures). Their descendants are the modern Volga Tatars. It was they, and not the Chuvash, who adopted Islam before Ibn Fadlan arrived in the Middle Volga region since there are no other Muslim peoples in the Volga region. Religious scholars know that people usually firmly adhere to the faith of their ancestors and do not change it without special reasons. The Anglo-Saxons could have adopted the Muslim faith, but they did not survive in these places, apparently assimilating among the Tatars. The Royal Scythians, having established a xenocracy in Khazaria, eventually assimilated among the peoples of the North Caucasus, which is why something similar happened in the Volga region.

From all this, it follows that the Bulgars were not the ancestors of the Chuvashes, they must have been Anglo-Saxons, and the peoples subject to them adopted a prestigious name. An example of this can be the name of one of the Slavic people in the Balkans. However, this ethnonym is of Chuvash origin, it consists of Chuv. pulkk 1. "pack, flock, gang"; 2. "crowd, gang, gang" and ar "man". In this case, the first word plays the role of a definition. Thus, while the Anglo-Saxons called their close neighbors "shooters" (Old English scytta, similar in sound to the Greek name for the Scythians Σκυθαι), the Chuvash called the Anglo-Saxons "Bulgars", referring to their herd lifestyle. The fact that a people can be called this way confirms the origin of this word and the development of its meaning in different languages. When some of the ancient Turks moved to the right bank of the Dnieper and lost contact with other Turks, the further development of their language was greatly influenced by the language of the Trypillians they assimilated. There is convincing evidence that the Trypillians were originally one of the Semitic tribes from Asia Minor that came to the Right Bank of Ukraine. Theo Vennemann compares Old Germanic *fulka (Eng folk, Ger. Volk) and also Eng. ploug, Germ. Pflug a.o. with Hebr plC, a family of related roots including plg, all meaning "to divide, separate" (VENNEMANN THEO, 2005, 27). This Semitic root has good correspondences in the Chuvash word mentioned and in the name of the ancient deity Pülĕkh "divider", "providence", distributing lucky or unlucky lots to people. The name of the Balkar people, who made up the bulk of the population of Khazaria, has the same origin.

If the Anglo-Saxons were only the ruling elite, then the bulk of the population of Bulgaria should have been Tatars as the creators of the Balanovo culture, which existed in the second millennium BC. Chronologically, this should mean that it was one of the later variants of the Corded Ware cultures. This explains the significant difference between the Chuvash and Tatar languages. In contrast to the separate development of the Chuvash language, the Tatar language developed for a long time and was close to other Turkic languages in their original places of residence. It acquired new features in common with them. At the end of the third millennium BC, the Turks began to settle in the vast expanse of Eurasia. Some of the Turks remained in Europe, including the Tatars, who chose the path to the Middle Volga region. When, three thousand years later, the Chuvashes met the Tatars in the Povolzhye region, they could no longer easily understand each other, as is typical for most Turks.

As the ruling class, the Anglo-Saxons held in their hands the organization of trade between Bulgaria and the countries of the Arab Caliphate through Khazaria. This was facilitated by the common language of the rulers of the two countries. In search of new, cheaper sources of fur production, the Anglo-Saxons moved further east, as evidenced by Anglo-Saxon toponymy. Having crossed the Ural Mountains, they created their own state in Western Siberia, which also enriched itself on the fur trade. This is evidenced by the decoding of the toponyms Pelym flows into (Old English fell "fur" and ymb "around"), Puksinka on the bank of the Pelym (Old English fox "fox", inca "grief", "quarrel", "suspicion") and Nikhvor (Old English neahhe "sufficient, abundant" waru "goods"). While in Russian service, the Russian-German historian Gerhard Müller (1705–1783) traveled across Siberia and collected extensive material for his work. He devoted many lines to the Pelym Principality, which existed until the end of the 16th century in the place of accumulation of Anglo-Saxon toponymy around the city of Tyumen. He mentions the campaign against the Voguls by Russian commanders at the head of an army of "4,024 nobles and boyar children" in 1499 (MILLER G.F. 1938: 203). Considering the current number of the Mansi people, as the former Voguls are now called (no more than 10 thousand people), they could not have assembled a large army at that time. In addition, other travelers, the envoys of Peter the Great to China in 1692-95, who became well acquainted with the Voguls on the road, describe their customs and way of life in such a way that it seems incredible that this people could previously have been so brave and warlike as to carry out military campaigns (IDES ISBRANT and BRAND ADAM. 1967: 71-77). There is no doubt that the Anglo-Saxons resisted the expansion of the Russians under the name of Voguls. Much earlier, groups of Anglo-Saxons from Western Siberia migrated east and reached Lake Baikal. They populated Dauria and eventually the Amur basin (for more details, see Opening of the Great Siberian Route).

In historical documents, the Bulgars were mentioned for the first time and only once by Herodan, and they are not even among the peoples of Scythia conquered by the Gothic king Hermanarich. Ibn Fadlan does not mention the Bulgars in the list of peoples he observed during his travels. It can be assumed that they were among the "others" on this list, which seems strange for a country called Bulgaria. He does not use this name and titled his "Note" a journey to the Volga and only mentions the king of the Bulgars three times (IBN FADLAN AHMAD. 1966). Most likely, this is an inaccuracy of translation; one should understand the formulation "King-Bulgar" as a title. The word, initially used as an ethnonym, over time and with the development of events became a definition of social status in society. Thus, the history of the fictitious nation of the Bulgars is an additional page in the history of the Anglo-Saxons (see Anglo–Saxon Agonality).