The North Caucasian Languages

It has been scientifically established that the settlement of the Caucasus dates back to ancient times and has passed through all chronological stages of human history, beginning with the Old Stone Age. Of particular interest is the diverse multi-ethnic landscape of the North Caucasus, which was settled from the Early or Lower Paleolithic period "within the range of 1.8 million to 600 thousand years to the present day" (SAVENKO S.N. 2011: 58). The North Caucasus includes the European space between the shores of the Black and Caspian Seas, bounded by the Main Caucasus Range and the Kuma-Manych Depression (Ibid 59). During the cold season, Paleolithic man found refuge in cave dwellings in the Caucasus much earlier than in neighboring regions of the Middle East.

The Caucasus is one of the first places (and possibly the first) by the number of sites of Stone man (LUBIN V.P. 1998: 49). By the end of the Acheulean period, people had already invaded the territory of modern Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the North Caucasus (sites in Azykh cave, Dmanisi, Kudaro, Muradovo, Tsona, Karakhach).

At left: Azokh cave in Azerbaijan, the site of Pre-neandertalian people. Photo from Wikipedia.

People of the Caucasoid type settled in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia during the Mesolithic and developed their own Neolithic cultures there. Recent paleogenetic studies have shown that the main anatomical features of Homo sapiens were present in Africa at least 150,000 years ago (STRINGER CHRIS. 2007: 15).

The African fossil record shows that the peopling of Eurasia from Africa continued for several tens of thousands of years, with the main route of human dispersal running along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea:

The extension of early modern humans to the Levant by 100 ka has been confirmed by further dating analyses on the Skhul and Qafzeh material [Ibid: 15-16].

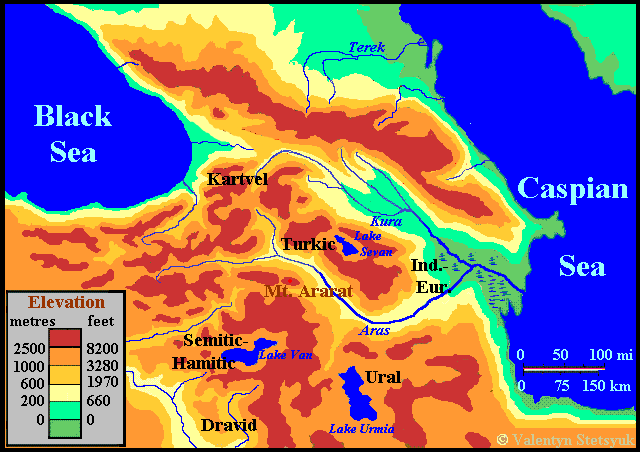

Thus, people from the Levant began to spread across Eurasia, during which time ethnic groups and their languages were formed. A study of the Nostratic and Sino-Tibetan languages using the graphoanalytical method revealed that they developed in the same place, namely, in the region of three lakes: Sevan, Van, and Urmia [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998; 27-32; The Formation of the Sino-Tibetan Languages and their Speakers Migration]. Initially, this territory was inhabited by people of Mongoloid anthropological type, who were later displaced by Europeans. Since the end of the Neolithic Revolution, archaeological research in the Caucasus has identified three cultural zones. Linguists correlate them with the speakers of the Kartvelian, Abkhaz-Adyghe, and Nakh-Dagestani languages [KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M.Sh. 2003: 17]. The Kartvelian languages, which belong to the Nostratic macrofamily and whose speakers originally lived in Transcaucasia, are considered separately. Here, we provide a map of their distribution (see map below) and will then attempt to clarify the possibility of an ancient population with a different linguistic affiliation being present in the Caucasus. The key question is whether any part of the modern population of this territory is indigenous. Although the data of ancient historians reflect a diverse, multi-ethnic picture of the Caucasus, attempts to answer this question have not led to success:

…accurate localization and identification with modern peoples and ethnic groups of the tribes mentioned by ancient writers are in most cases difficult or even impossible (GADZIEB M.S. 2019: 18).

At right:Areas of formation of Nostratic languages

Abbreviations

Dravid. – Dravidian languages

Ind-Eur. – Indo-European languages

Kartvel. – Kartvelian languages

Ural. – Uralic languages

Localization of the ancestral homelands of the languages of the modern peoples of the North Caucasus using the graphic-analytical method allows us to restore their history more definitely. Currently, speakers of the Nakh, Dagestani, Abkhaz-Adyghe, and Turkic languages live here. The Balkars, Karachays, Kumyks, and Nogays are more recent arrivals. Therefore, we must establish the family ties of the Nakh, Dagestani, and Abkhaz-Adyghe languages and, using graphoanalytical models of these languages, attempt to locate the ancestral homeland of their speakers.

Many linguists group the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani languages into a single North Caucasian family, sometimes simply called Caucasian. The South Caucasian languages include the Kartvelian languages, which, as noted, belong to the Nostratic macrofamily, while the relationship of the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani languages to any macrofamily has not yet been determined. Since their speakers have lived in the Caucasus since ancient times in proximity to speakers of Kartvelian languages, it can be assumed that these languages also belong to the Nostratic family.

Lexical data on North Caucasian languages was compiled into tables by a group of scientists led by Nikolai Starostin in the The Tower of Babel project. The data taken from the tables were used to study these languages using a graphoanalytical method, but it was not possible to construct a general relationship model for them. However, separate models for the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani languages were successfully constructed. We will consider the languages of these language families separately.

The Abkhaz-Adyghe languages

The Abkhaz-Adyghe languages are represented by the living languages Abkhaz, Abaza, Adyghe, Kabardino-Circassian, and the extinct Ubykh language, for which documented evidence remains. Kabardino-Circassian and Adyghe are so closely related that it can be assumed that they share a common origin from a single proto-language. A less certain assumption about a common proto-language between Abkhaz and Abaza is possible. Nevertheless, to construct a graphical model of the relationship, Sergei Starostin's data for all five Abkhaz-Adyghe languages was used.

In accordance with these data, the relationship scheme is constructed very easily, it is shown at the left.

At left: The graphical model of the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages.

Presumably, the resulting map location should be sought somewhere near modern settlements of the Abkhaz-Adyghe peoples, but the small number of languages spoken in this group makes it difficult to pinpoint their prehistoric homeland. Under this assumption, the map could be located in the Western Caucasus, where five distinct geographic areas delimited by rivers and the Main Caucasus Range can be identified along the Black Sea coast. The ancestors of the Adyghe, whom we will provisionally call Adyghe, would have lived in the area between the Mzymta and Bzyb rivers, while the ancestors of the Ubykhs would have lived between the Mzymta and Shakhe rivers.

The map of areas of the formation of the Abkhazo-Adyghean languages on the West Caucasus.

The presence of an area between the Kelasur and Kodori rivers corresponding to the kinship model suggests that the Abazin language developed exactly there, in the neighborhood of the Abkhazian area, and this caused the special proximity of these languages. The Abazins are the ancestors of the historical Abazgs (Abaska), whose country was located approximately in the same places.

The Nakh-Dagestani languages

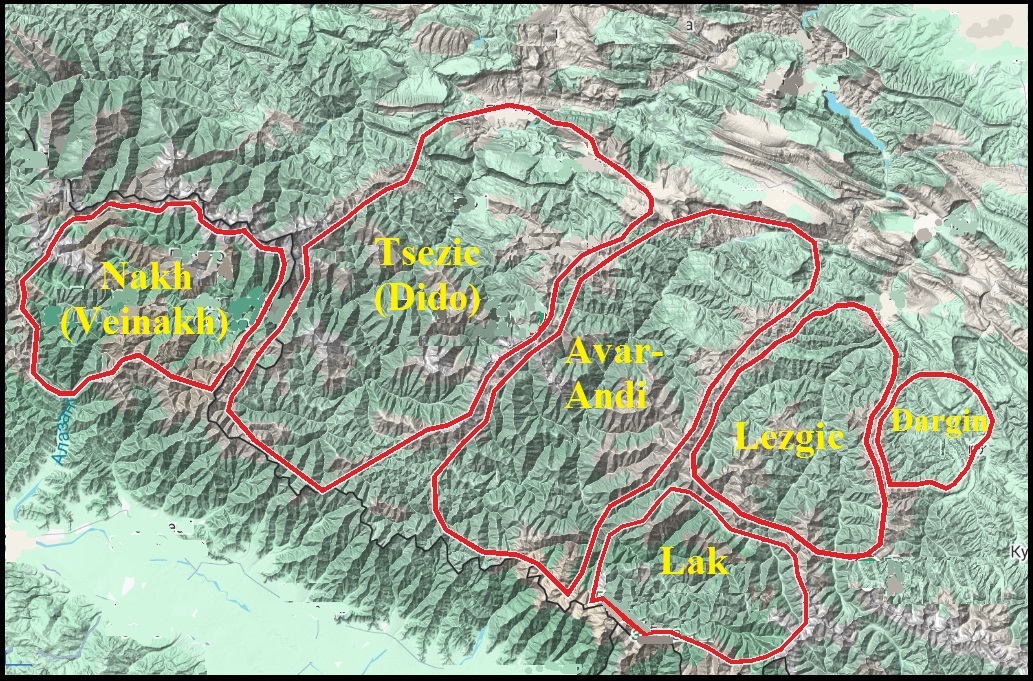

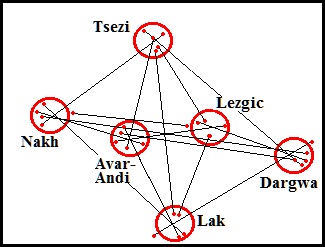

According to the classification of S. Starostin, the Nakh-Dagestani languages include the Lak and Dargin (Dargva) languages, as well as the following language groups: Nakh (Veinakh), Tsezic, Avar-Andi, and Lezgiс.

Apparently, the parent language that was once common to the entire population of Dagestan was divided into six separate proto-languages corresponding to the designated classification. Based on data from Tower of Babel, a graphical model of their relationship was constructed, which looks like the figure on the right.

At right: The graphical model of the Nakh-Dagestani proto-languages.

The very possibility of constructing a diagram confirms this division of the Nakh-Dagestani languages, but it is also possible to place it on a map of the North Caucasus. In the valleys bounded by the ridges of the mountainous country of Dagestan, a complex of ethno-forming areas formed, within which the resulting diagram fits well (see map in the figure below).

The areas of formation of the Nakh-Dagestani proto-languages along the northeastern slopes of the Main Caucasus Range.

As can be seen from the map, the area of the Nakh proto-language can be located in the valleys of the Alazani River tributaries, along the upper reaches of the Andi Koysu River and its left tributary, the Perikatelskaya Alazani, in northeastern Georgia. Speakers of the language that gave rise to the Tsezi (Dido) languages must have inhabited the Andi Koysu River valley, while the ancestors of the speakers of the Avar-Andian languages lived along the banks of the Avar Koysu River. The Lak language apparently developed in its upper reaches, called the Jurmut. The original dialects of the Lezgiс languages may have developed in the valleys of the Kara Koysu River and its tributaries, and the Dargin language along the banks of the Tsamtichai River. The dense network of mountain ranges, although creating a fairly large number of isolated ethnoforming areas, allowed the population to migrate through accessible passes. As the population grew, the need for migration and further dispersal of speakers of the Nakh-Dagestani languages along the Greater Caucasus Range must have arisen. Consequently, in new settlement sites, some languages of each of the four aforementioned groups split into separate dialects, giving rise to new languages. For existing closely related languages of these groups, relationship graphs were constructed using the same data, and an attempt was made to locate the corresponding ethnoforming areas in the area closest to the areas of the original languages. As a result of this attempt, a map of the areas where all these languages were formed was compiled (see below).

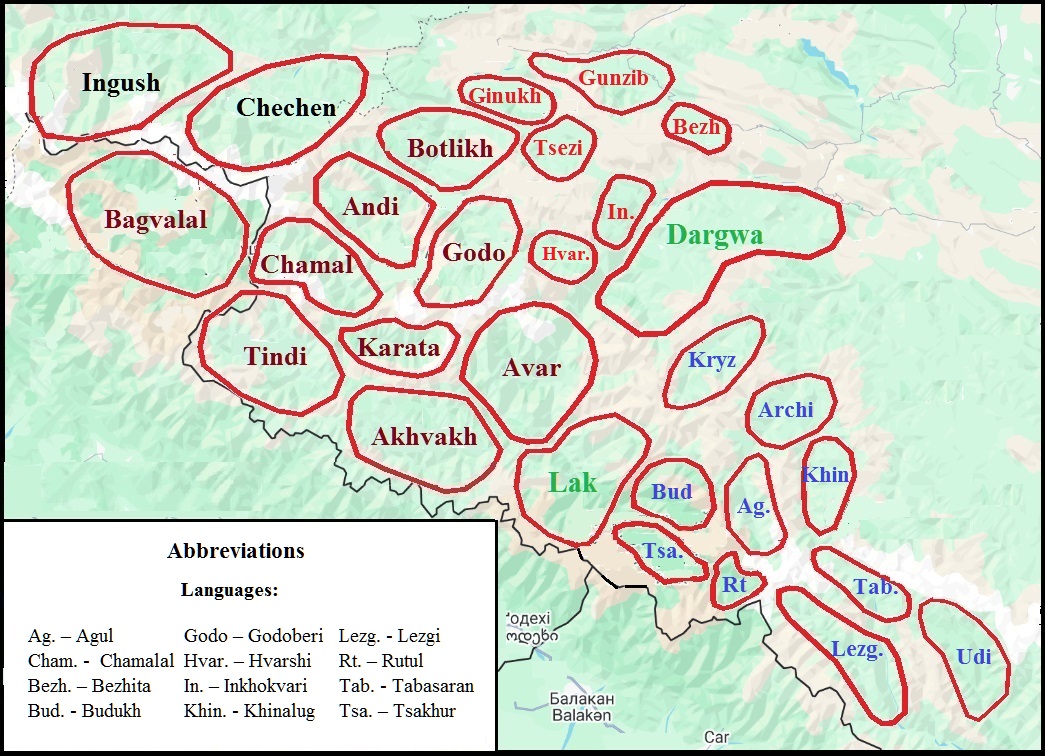

The areas of formation of the current Nakh-Dagestani languages.

On the map, the names of the Veinakh languages are shown in black, the languages of the Avar-Andic group are shown in brown, the Dido group in red, and the Lezgic language in blue. The color green was used for the Lak and Dargin languages.

To determine whether the resulting map corresponds to reality, we should check the feasibility of placing the resulting graphs on the map and seek additional evidence for such placement. This could include the modern settlements of speakers of the languages and their groups in question. Let's examine this possibility one by one.

Languages that developed from the Nakh proto-language.

The Nakh proto-language gave rise to the current Chechen, Ingush, Batsbi, and Kistin languages. Apparently, the ancestors of the Chechens and Ingush left their ancestral homeland under pressure from the Avar-Andean tribes who arrived through the Tsuntinsky Pass (2,464 meters above sea level) from the Avar Koysu River valley. After crossing the pass between Mount Bolshoye Borbalo on the Main Caucasus Range and the Nukatl Range, the Nakh tribes reached the upper reaches of the Argun and Sharoargun Rivers and settled the valleys of both rivers. The Chechen and Ingush languages, which form the Veinakh group, finally developed in these valleys. This does not contradict the current distribution of the Ingush and Chechens. The ancestors of the Batsbi and Kistin peoples remained in the old settlement sites, and their languages developed there under the influence of Georgian.

Languages that developed from the Avar-Andi proto-language.

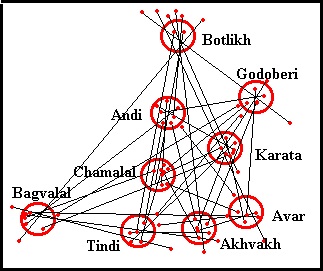

The constructed diagram of the relationship of modern languages of the putative Avar-Andean group is shown in the figure below.

Left: The graphical model of the Avar-Andean languages.

The resulting model can be placed in the upper reaches of the Avar and Andi Koysu Rivers, assuming that some speakers of an originally common language migrated upstream along the Avar Koysu River and crossed through the passes in the Bogos Range into the Andiyskoye Koysu valley. .

This assumption corresponds fairly well to the areas of formation of the Andiyskoye and Botlikh languages, whose speakers now primarily reside in the Botlikh District, and the area of Chumalal, whose speakers live in the neighboring Tsumadinsky District and a short distance away in Chechnya. To a certain extent, this also applies to the Bagvalal language, which developed in the same area where the Nakh proto-language arose, that is, in Georgia. Currently, Bagwala speakers (also known as Bagulal) do not form a majority in any district of Dagestan, but they reside in an area adjacent to their historical homeland, the Tsumadinsky District of Dagestan. The distributions of the Karata and Godoberi languages generally do not contradict the relationship diagram, as their languages are spoken in neighboring districts, just as their areas are adjacent in the diagram. Nothing definitive can be said about the correspondence of the diagram to the modern residences of Avar and Tindin speakers. Avar is the lingua franca in Dagestan, and many other peoples consider themselves Avars, while the few Tindin speakers live scattered across various districts. The only serious contradiction to the diagram is the distribution of the Akhvakh language far from its presumed ancestral home. This may be due to later migrations of the Akhvakh people, but it is also possible that linguists have made mistakes in studying the relationship of languages in this group.

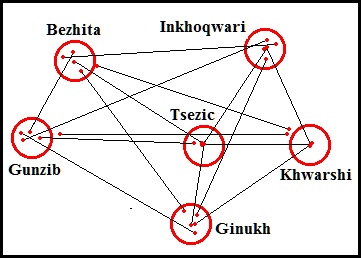

Languages developed out of the Dido (Tsezic) proto- language..

A diagram of the relationships of modern Dido languages, constructed based on available data, is shown in the figure below. These include Bezhta (Bezhita), Ginukh, Gunzib, Inkhoqvari, Tsezic, and Khvarshi.

At left: The graphical model of the Dido (Tsezi) languages.

According to the relationship model, the Dido languages should have formed in the lower reaches of the Andi and Avar Koisu rivers. This is precisely where it fits quite well. This assumption also corresponds to the placement of the Dido language on the general relationship map of the Nakh-Dagestani languages. These are the Gunib, Gumbet, Gergebil, Khunzakh, and Untsukul districts, whose populations identify as Avars

Speakers of the Dido languages are virtually nonexistent here; most live farther south, particularly in the Tsumadin, Tsuntin, and Bezhta districts. Corresponding place names are also found there (Bezhta, Gunzib, Inkhoqvari, etc.). It can be assumed that at some point, groups of Dido speakers migrated south due to the invasion of newcomers. Moving up the Andi Koysu valley, the settlers were unable to find a place for themselves among the Avaro-Andians until they reached the upper reaches of the Metlyuda and other tributaries of the Andi Koysu. They settled in these valleys and lived in scattered villages, intermingling with each other and the Avars, preserving their native languages. The newcomers who forced them to embark on this long journey were apparently the Kipchak tribes, whose descendants are the modern Kumyks. This hypothesis is supported by local toponymy, particularly the names of rivers containing the element Koysu, which are clearly of Turkic origin (quj, qoj "to pour, to flow, to flow", su "water"). Over time, the Turks must have moved back, because there are currently no Turks in the Andi and Avar Koysu basins, nor in the Karakoysu basin.

Lak and Dargva languages.

Apparently, some Laks remained in their ancestral homeland and still live there today in the Charodin District, as well as in the Lak and Kulin Districts of Dagestan, preserving their single language with minimal changes. In contrast, the ancestors of the Dargins must have dispersed throughout the immediate area to the northeast and southwest. They undoubtedly inhabited the lower reaches of the rivers flowing to the Caspian Sea. There are no significant geographical barriers here, so the Dargva language did not undergo the process of fragmentation. Its speakers spread over a wide area, apparently reaching the Sulak River. The aforementioned Kipchaks, having arrived in the Ciscaucasus, advanced toward the Caspian Sea south of the mouth of the Terek and occupied part of the Dargin territory in the steppe foothills and along the sea, pushing the Dargins beyond Derbent. Evidence of this is the modern settlements of Kumyks in several foothill regions of central Dagestan.

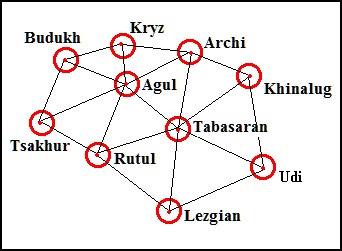

Lezgian languages

Driven out of the Karakoysu Valley by the Dargits, the ancestors of the Lezgin speakers moved to the upper reaches of the Samur and Khunnikh rivers. The modern settlements of this group of peoples only partially correspond to the constructed model of the relationship of their languages, shown below.

At left: The graphical model of the Lezgin languages.

According to the diagram, the Rutuls and Tsakhurs dwell in the Rutul district of Dagestan, the Lezgins in the Akhtinsky, Magaramkent, and Kurakhsky districts, the Aguls in the Agul district, and the Tabasarans in the Khivsky district. The locations of the minority peoples do not correspond at all to the map. For example, the Archins, along with the Avars, reside in the Charodin district of Dagestan. The Budukh and Kryz peoples inhabit several villages in Azerbaijan. The Udi people are found in various places, including Azerbaijan, Georgia, Dagestan, and even Kazakhstan.

C. Starostin included the Khinalug language into the Lezgin branch of the Dagestan languages, but according to recent studies, it is a separate branch. A small number of native speakers of this language live in Azeobaydzhan (KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M.Sh. 2003: 13)

Summarizing the obtained data, we can reconstruct the linguistic situation in the Caucasus at the time of the formation of the original languages. It is believed that the formation of linguistic communities in the North Caucasus occurred in the late Neolithic and Eneolithic periods (SAVENKO S.N. 2011, 61), and their settlement took place through accessible passes and mountain passes from Transcaucasia (Ibid., 60). It is also assumed that the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani languages derive from a single common ancestor, which S. Starostin called the Proto-North Caucasian language (PNC). As evidence of its existence, he cited phonetic and lexical correspondences between the Nakh-Dagestani and Abkhaz-Adyghe language (STAROSTIN S.A. 2007: 290-305). As it turns out, these correspondences can be largely attributed to the common Nostratic fund. The existence of numerous Indo-European-North Caucasian isoglosses has long been known (ibid, 312-358), and a study of the lexical core of both language families, containing the most ancient words, showed that their languages have quite a few correspondences in Turkic languages. Moreover, such correspondences are more numerous in the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages, while Indo-European correspondences are more numerous in the Nakh-Dagestani languages (см. On the Relationship of Nostratic and Caucasian Languages). This gives reason to assume that speakers of the Nakh-Dagestani and Indo-European proto-languages were in proximity in prehistoric times on the territory of modern Azerbaijan. The Kura River could have been the border between their ranges.

Having left their ancestral homeland in the Kura Valley for unknown reasons, the speakers of the Nakh-Dagestani proto-language crossed the passes of the Caucasus Mountains. Some of the settlers found Dagestan a suitable place to live, while others were destined to descend further into the plains and become the founders of the so-called Maykop culture, which existed in the Ciscaucasia until the end of the third millennium BC. This population can be roughly called Maykopians (see Maykopian Enigma). To this day, no traces of the Maykopians' ethnicity remain. At some point, under pressure from newcomers of a different ethnicity, they migrated in an unknown direction, presumably eastward. Conversely, the indigenous population of Dagestan has survived to this day, living alongside these and later newcomers (more on this below).

Thus, the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani languages, grouped under the general heading of North Caucasian, do not share a common ancestor. The relationship of individual proto-languages of both these families pertains to a larger Nostratic community, the composition of which should be expanded and its existence dated back to biblical times. All obtained data is entered into the Google My Maps system, and the resulting map is shown in the figure below.

.At left: Linguistic map of the Caucasus for about the period of 7-5th millennium BC

The research also suggests that, with the exception of the Maykopians, the earliest inhabitants of the Caucasus remained in or near their original settlements until today. Here, the ancient Kartvelian proto-language underwent the process of fragmentation into distinct dialects, which later evolved into modern Georgian, Megrelian (Mingrelian), Laz, and Svan. However, new settlers arrived in the Caucasus from time to time.

Left: The population of the Caucasus at the Scythian time

At the turn of the 3rd and 2nd thousand BC, during the First "Great Migration of Peoples", the North Caucasus was populated by Turkic tribes (the ancestors of modern Turks, Kumyks, Karachays and Balkars, Turkmen, and Gagauz). Later, Armenians and Iranian Medes tribes settled in Transcaucasia, soon joined by other Iranians: Talysh, Gilyanians, Balochi, and Masendaran. The Albanians and Caspians, known from history, who inhabited the Transcaucasus in the Scythian time, obviously belonged to that part of the speakers of the hypothetical North Caucasian language, which remained in its historical ancestral homeland. The Kolkhs mentioned in historical documents were the ancestors of modern Megrels and Laz.

The Ossetians, who constitute a significant part of the population of the North Caucasus, came to their present habitat in historical times. The ways of their migrations are reflected in place names. They, as with other peoples of the North Caucasus, in particular the Adyghe and Chechens, played a great historical role in the Scythian-Sarmatian period (see "Cimmerians" and "Pechenegs and Magyars". By the 20th century, the diversity of the Caucasus population had increased even more (see map below).

Right: Ethno-Linguistic map of Dagestan at the middle of the 20 cen.

The Kartvelian languages 1. Georgian

The Nakh languages

7. Chechen 8. Ingush 9. Kisti 10. Batsbi

The Dagestani languages

11. Avar 12. Lak 13. Dargwa 14. Tabasaran 15. Lesgi 16. Aguli 17. Rytul 18. Tsakhur 19. Khinalugi 20. Kriz 21. Budukh 22. Udi

The Turkic languages

34. Azerbaijan 35. Karachay 36. Balkar 37. Kumyk 38. Nogai 39. Turkmen 40. Tatar 41. Kazakh

The Indo-European languages 23. Russian 24. Ukrainian 25. Armenian 26. Ossetic 27. Kurdish 28. Talishi 29. Tatish 30. Jewish-Tatish 31. Greek 32. German 33. Romanian

A comparison of the maps of the areas of formation of the Nakh-Dagestani languages with the modern settlements of their respective speakers showed that they were indeed formed on the territory of Dagestan, and we see that the related Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani languages underwent the process of division at a fairly large distance from each other, i.e., they have lived in these territories for a historically long time.