An Old English Inscription in the Caucasus

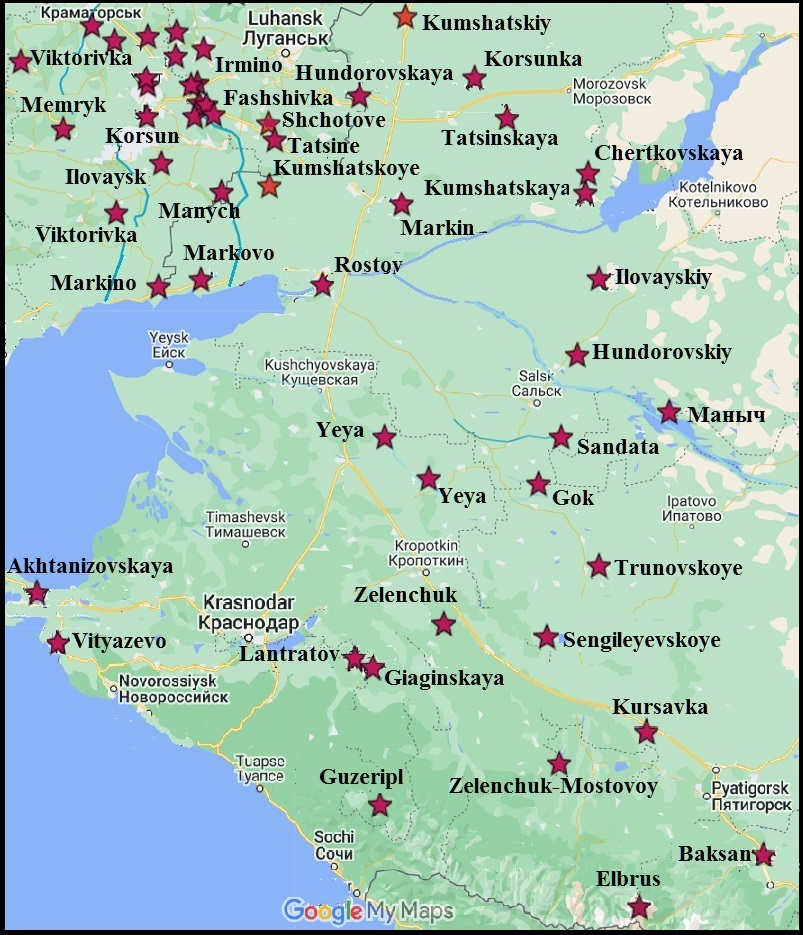

Присутствию англосаксов в Восточной Европе я посвятил несколько статей, тексты которых можно найти в Интернете. Многочисленные факты дают основание утверждать, что в составе племенного союза алан были англосаксы. Предлагаемая вниманию читателей статья не только подтверждает это утверждение, но и дает материал для восстановления истории формирования современного английского языка. Спасаясь от нашествия гуннов, основная масса аланов отошла на запад, на территорию готов, с которыми они связали свою дальнейшую судьбу. Меньшая часть мигрировала на Северный Кавказ и этому есть свидетельства в местной топонимии (см. карту ниже).

Англосаксонская топонимия в Приазовье и на Северном Кавказе.

In 1888, on the right bank of the Bolshoy Zelenchuk River, a stone stele with an inscription in Greek letters was found 30 km from the village of Nizhniy Arkhyz (see the figure on the right). The decoding of the inscription was made by V.F. Miller using the Ossetian language. With small corrections, the reading is now accepted in science, and the dating of the stele is determined by 941 AD year (DHURTUBAYEV M. 2010: 198).

Miller believed that there was a Christian city in this area, from which the ruins of churches were preserved, and suggested that it was the center of the Alan diocese (metropolis), which is mentioned in Byzantine literature. However, not all agreed with the decoding of Miller, because he introduced eight additional letters into the text, which were absent on the stele and without which it can not be by means of the Ossetian language (Ibid).

At left: Drawing of the inscription of Zelenchuk stele in Dhurtubayev'в book taken from V.A. Kuznetsov (Ibid: 199).

The inscription has various reading options, including the use of Ossetian, Kabardian, Karachay-Balkarian, Vainakh, and, possibly, other languages, and disputes about its language continue to this day. The stele itself was not preserved; attempts to find it in 1946 and 1964 did not bring success (KAMBOLOV T.T. 2006: 166).

Without the original, one cannot speak about the accuracy of text rendering, and this additionally complicates the decoding of the inscription. The strange thing in this story is that Miller, Abaev, and other experts in Iranian languages did not give decryption of the name Arkhyz itself, which could add them confidence about the Ossetian origin of the stele.

The fact is that in the mountainous region of Arkhiz there are several toponyms that are decrypted precisely with the help of the Ossetian language:

Arkhyz, a river, lt of the Psysh, lt Of the Great Zelenchuk, lt of the Kuban River – Os. ærkh "piece" "splinter", "sliver".

Kardonikskaya, a stanitsa (village inside a Cossack host) in Zelenchuk district of Karachay-Cherkessia – Os. kærdo "rear-tree", nigæ "riverside covered with grass".

Mara, a river, rt of the Kuban' River – ос. mæra "hollow".

Synty, the former name of the aul of Lower Teberda in Karachai-Cherkessia – Os. synt "raven", syntæ "net, snare".

Zagedan, a town and a river, rt of the Bolshaya Laba River in Karachay-Cherkessia – Os. dzag "full", don "water, river".

Such an accumulation of Ossetian place names on a small territory indicates the presence of the Ossetians at some time in Alania, which could be reflected in written sources. Subsequently, the Ossetians could be forced out by the Alans to the places of their modern emplacement, and this entailed confusion in the localization of Ossetia, which Zuckerman notes:

… having only inaccurate translations, Muller made almost surreal conclusions about the location of ethnic groups: he placed the Alans in the west, at the source of the Kuban River, the Ases to the east, then again the Alans – even further east, in the country of Ardoz (ZUCKERMAN C. 2005: 78).

In turn, Zgusta, having no reliable historical evidence and even without a clear idea of the places of Ossetian settlements in the Caucasus, made a hasty conclusion about the Ossetian text on the stele and declared the existence of Ossetian writing already in the Middle Ages. No other data confirming this conclusion has been found so far, however, the authority of L. Zgusta, who saw in the text a relic of the Proto-Ossetian language (ZGUSTA LADISLAV. 1987), contributes to the fact that Abaev’s conclusion still has adherents.

I read the inscription in Old English, which may cause bewilderment if one did not know that there were also Anglo-Saxons among the multinational population of the North Caucasus. I devoted several articles to the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe, the texts of which can be found on the Internet. Numerous facts give grounds to assert that the Anglo-Saxons were part of the tribal union of the Alans. Fleeing from the invasion of the Huns, the bulk of the Alans retreated to the west, to the territory of the Goths, with whom they linked their future fate. A smaller part migrated to the North Caucasus and there is evidence of this in the local toponymy.

Righ: Anglo-Saxon toponymy in the Azov region and the North Caucasus.

Place names mark the path of the Alans from the Donbas to the foothills of the Caucasus and their settlement in Caucasian Alania. The most convincing examples are given below:

Yeya, a river flowing to the Azov Sea and originated names from it– OE. ea "water, river".

Sandata, a river, lt of the Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don River – OE. sand "sand", ate "weeds".

Bolshoy and Malyi Gok (Hok in local pronunciation), rives, rt of Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don – OE. hōk "hook".

Zelencuk, names of about a dozen rivers and settlements in the Kuban and Ukraine. The large distribution and unusual shape testify against the Slavic origin of the name– OE selen "tribute, gift", *cūgan "oppress" restored from OE Сūga – the personal name which Holthausen associates with Icl. kūgan "tyranny", kūgi "oppressor" (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1074: 62).

Sengileevskoe, a village in the Shpakovski district of Stavropol Krai – OE. sengan "singe", leah "field".

Guzeripl' (Huzeripl' in local pronunciation), a settlement in the Maikop municipal district of the Republic of Adygea – OE. hūs "house", "place for house", rippel "undergrowth".

Baksan, a river and a town in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE. bæc "back", sæne "slow".

Mount Elbrus, mountain peak in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE äl "awl", brecan "to break", bryce "fracture, crack", OS. bruki "the same", , k alternates with s.. Elbrus has two peaks separated by a saddle.

Elbrus

Photo by the author of the essay "My trip to Elbrus"

Among all the toponyms of the alleged Anglo-Saxon origin, there are similar names that have interpretations in Old English, but not all of them could have been appropriated by the Anglo-Saxons, but were given by the later population during resettlement to a new location, by analogy with the names of former settlements. It is very difficult to single out the Anglo-Saxon ones, so they were all mapped, which to a certain extent increases the density of the Anglo-Saxon place names and, as a result, gives an erroneous idea of the number of Anglo-Saxons living in the North Caucasus. Similar names and their etymologies are given below:

Hundorovskaya, Hundorovskiy – OE. hund "dog", ōra "bank, edge".

Kumshatskaya, Kumshatskiy, Kumshatskoye – OE. cumb "valley", sceatt "wealth, property”.

Markin, Markino, Markovo – OE. mearc "border, end", "sign"; mearca "determined space, district".

The same may be said about identical names:

Yeya – see above.

Manych, – OE. manig "many", yce "frog".

Having advanced into the North Caucasus, the Anglo-Saxons conquered the local population, as evidenced by the names of Zelenchuk, and continued to play a leading role in the political life of the Northern Black Sea region. This gives grounds to assume that the formation of the Khazar Khaganate was not without their participation (see the article Khazars). This hypothesis is not perceived by experts as having any convincing evidence. This is how Peter Golden described it in private correspondence with me. I think that if he had not looked for refutation, but looked for confirmation of the hypothesis, he would have found them, apparently, quite a lot. The truth must be in the details. Also, no one else tried to do this, but I did not specifically deal with this issue. However, accidentally discovered information strengthens my confidence in my own rightness. As it turned out, the name of one of the Alanian leaders Sarosius (512? -596) can be deciphered with the help of OE. searo "skill, craftsmanship". According to a historical document, he was a prince, that is, he was at the head of some kind of state formation, with which Caucasian Alania can be associated. The information about him survived only because the Avars' invasion of the Northern Black Sea region caused concern in Byzantium, and Sarosius became an intermediary in their relations with Emperor Justinian. The lack of historical documents about other Alanian rulers of early times can have various reasons. It may be that they were not carefully looked for.

Now, after the necessary introduction, we can proceed to our topic of reading the inscription on the Zelenchuk stone. I wrote the clearer signs on the stele as follows: νικολαοσ σαχε θεφοιχ ο βολτ γεφοιγτ πακα θαρ πακα θαν φογριτ αν παλ αμ απδ λανε φογρ – λακα νεβερ θεοθελ. Принимая во внимание соответствие греческих и английских букв, я переписал надпись так: nikolaos saxe thefoix o bolt gefoigt paka thap paka tan fogrit an pal am apd lane fogr – laka neber theothel. I propose the following decoding of the inscription: "Sachs Nikolai is buried here, doomed to death by a traitorous arrow of an insidious servant, decorated with a strong pillar decorating the path – a gift from his nephew Theophilus".

The inscription does not have a clear division of the text into words, I did it at my own discretion. The suggested words are discussed below:

1. νικολαοσ (nikolaos) – there is no doubt that this is the name of the alleged buried Nicholas (Gr. Νῑκόλαος).

2. σαχε (saxe) – the word is distinguished on the stele with intervals and can mean a surname, status, or nationality. OE Seaxe “Saxon” and OS. Sahse “the same” suit best of all.

3. θεφοιχ (thefoix) – the keyword of the inscription, on the sense of which the whole meaning of the inscription depends. I propose for consideration OE. đafian in German “gestatten, einräumen; erlauben, dulden; billigen, zustimmen” which is connected with Gr τοποσ "place, space"(Holthausen F./ 1974: 360). The first two words in German have approximately the same meaning “to let, allow, permit”, but in Ger. einräumen still has the basic meaning “to lay down, put, stow”, which corresponds to the components of the word ein “in” and Raum “space, room, place”. Ger gestatten also contains a word meaning “place” (Stätte) and Ger bestatten “to bury, inter” comes from it. It follows from this that the meaning “to let, allow, permit” is also derived from the original “to lay down, put, stow”. Obviously, a similar metamorphosis occurred with OSax. đafian “to allow, suffer, endure, permit, tolerate”, i.e. meaning similar to German words. Taking all this into account, we assume that the word θεφοιχ is derived from đafian and, perhaps, it should be broken like this θεφο-ιχ, where ιχ is the local case of the verb in the third person singular (is), then thefoix has to mean "is buried".

4. ο βολτ (o bolt) – OE, OSax. bolt “arrow”, OSax. o = on, of, that is o bolt indirect case from bolt.

5. γεφοιγτ (gefoigt) – OE., OSax. fæge “to doom to death”, ge- is a prefix that intensifies the action of the verb and indicates completeness or perfection.

6. πακα (paka) – OSax. pæca “deceiver, swindler”.

7. θαρ (thar) – OE. đār (a) “here, there”, OSax. đǣr “there”.

8. πακα θαv (paka dan) – OSax. pæca "deceiver, swindler", OSax. đǣn = đegn “servant, vassal”.

9. φογριτ (fogrit) – OE., OSax. fæger “beautiful”, fægrian “to beautify”.

10. αν (an) – OSax. ān “strong, sturdy”.

11. παλαμ (palam) – the dative from OE., OSax. pāl “pillar”.

12. απδ (apd), obviously a rendering error, it should have been ανδ – OE., OSax. and “and”.

13. λανε (lane) – OE, OSax. lane “way”.

14. φογρ (fogr) – se. φογριτ.

15. λακα (laka) – OE. lācian “to present, donate”.

16. νεβερ (neber) – OE, OSax. nefa “nephew, grandson”, -r – the suffix.

17. θεοθελ (theothel) – Theophilus (гр. Θεόφιλος).

Possibly, Sakz, Cumanian Khan, the brother of Begubars, was buried here. Judging by the names of the Cumanian Khans, in the annals, the common name of the Cumans was understood to mean various peoples who inhabited the North Caucasus and the shore of the Sea of Azov. Among them were the Alans-Angles. The name of the brother of Sakz Begubars can be deciphered with the help of OE. beg “berry” and ūfer “shore” (together “currant”, cf. Ukrainian porіchki bank berry “the same”). Other Anglo-Saxons among the Cumanian Khans could be Iskal and Kytan.

The morphology of the language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons of Alania remains unknown to us, so it is not possible to accurately translate the Zelenchuk inscription. However, its interpretation given above should be close to the original in meaning. And if the Germanists undertook a careful study of the inscription, they could obtain evidence of an older English language than that which is now called Old English. The language of the Anglo-Saxons of Alania could preserve some of its relics.

The names of the kings of Alania may indicate that the Anglo-Saxons were the ruling elite of the kingdom. Queen Tamara of Georgia (r. 1184-1213) was the granddaughter of the “King of the Alans” Huddan, and his name can be understood as a "Person of high dignity" (OE. had/hæd "person", "rank", "dignity",dūn "height", "mountain"). In turn, the queen married David Soslan, supposedly some Alanian prince. The name Soslan can be associated with OE. sūsl "suffering, torment" (-аn – the suffix) and other similar words. Such an interpretation does not correspond to a high origin, but the fact is that nothing is known about the ancestors of Soslan. It is assumed that royal dignity could be attributed to him for political reasons in later times. (LATHAM-SPRINKLE JOHN. 2018: 20-21).

The Hungarian monk Julian left some information about Caucasian Alania. He visited it in 1235 during the search for the ancestral home of the Hungarians on behalf of the Hungarian king Bela, moving from the city of Matrika in the country of Sykhia on the western slopes of the Caucasus:

… the inhabitants (of this country – VS) represent a mixture of Christians and pagans: how many towns, so many princes, of whom no one considers himself subordinate to another. Here is the constant war of a prince with a prince, a small town with a town: during the plowing, all people of one place armed together go to the field, together mow, and then on the adjacent space, and in general coming out of their settlements for the cutting of firewood, or for whatever work, they all go together and armed, and in a small number they cannot go out safely from their settlements (GARDANOV V.K. 1974: 33)

It is clear from the description that there was no tribal alliance or the leading tribe in Alanya that can be spoken of. If there were Anglo-Saxons in these places, then they would have existed in very small numbers. William Rubruk, sent by King Louis IX, was ambassador to Mongolia in 1253. He met with the Alans in the Crimea and noticed that they are called there the Aas (RUBRUK WILHELM de, 1957: XIII). He also noted that the Alans do not drink Kumys, from which it can be concluded that they were not Turks, as Kumys is their national drink (Ibid: XII). Furthermore, he sometimes mentions the Alans in the North Caucasus and, in particular, notes that they were excellent blacksmiths. Alans could learn the blacksmith's craft during their stay in the Donbas.

Distribution map of "Alan" antiquities

according to [Zuckerman C. 2005: 72, Fig 1].

At one time, it was suggested that Alania be divided into East and West Alanya (that is, Alanya proper). Allegedly, in each of these parts of the country, a separate dynasty ruled, and each had its own original material culture. The author of the idea proposed his own delimitation of the early medieval archaeological cultures, which “reflects a very long coexistence in the north of the Caucasus of two main ethnocultural regions – the steppe (included in the region of the steppe cultures of the Northern Black Sea region, the Sea of Azov region and the Volga region) and the mountainous (properly Caucasian) one … ” (KUZNETSOV V.A. 1973: 73).

However, this theory turned out to be unsupported by the evidence. On the contrary, the sources clearly show that Alanya had only one ruling dynasty at any given time, although it is doubtful how much its people identified with the country or dynasty (LATHAM-SPRINKLE JOHN. 2018, 3). The opponent of the theory claims:

… whilst there is evidence for regional diversity in these sources, it cannot be summarised as a distinction between two long-lived, dynastic, territorially bounded polities. (Ibid: 5).

In addition, there is reason to believe that the term *As opposed to the Alans by V.A. Kuznetsov, does not contain a sign of ethnicity but is an identifying word for any Central North Caucasian tribe, and it retains this meaning in a number of regional languages. In Abkhazian, for example, all the peoples of the North Caucasus are called Ases. This meaning – or more precisely, the use of the term "As" or "Os" to designate a certain community of the valley – is also found in the languages of the North Caucasus (Ibid: 11-12). Moreover, even the Chuvashes, especially the older ones, still say: “Epir Asem” (we are Ases). Just the Ossetians call the Balkars the Ases too. However, they themselves are called by a similar word the Ases (Avses) by the Georgians. At the same time, there is no single self-name for Ossetians, their widespread name comes from the Georgian, and the self-identification of individual Ossetian sub-ethnos (Digorians, Irons, etc.) do not contain any hints of the ethnonyms of Alans or Ases.

If the term *As originally referred to a local community, this may suggest that the primary method of self-identification within the Central North Caucasus remained the local community, rather than ethnicity or kingdom. In any event, it seems that the distinction between the terms *As and Alan was a complex one, which changed considerably over time, and cannot, as Kuznetsov suggested, be explained as a longstanding, binary ethnic or political division (Ibid: 12)

News of the Alans in the Caucasus came from travelers in the Caucasus until the 18th century. The last evidence of the presence of the Alans north of the Klukhor pass in the amount of “one thousand souls” was the message of Jan Potocki in 1797 (ZUCKERMAN C. 2005: 82).

There are uncertain assumptions about the existence of an English colony in the North-Eastern Black Sea, based on the reports of medieval chronicles about the flight of part of the Anlo-Saxons after the Norman conquest in 1066. Indeed, there is no doubt that the imperial guard, which existed until the siege of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204, also included “English Varangians”. The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in Constantinople could be associated with memories of their distant ancestral home in the east. After some time, some of them wanted to establish their own kingdom and asked the emperor (Alexios Komnenos?) to provide them with several cities where they could merge. Allegedly, they were given territory somewhere on the northern coast of the Black Sea (GREEN CAITLIN R. Dr. 2015). At that time, the Byzantines, busy fighting the Turks and problems with the Crusaders, were not interested in these lands and what was happening there was unknown to them. However, the settlements of the Anglo-Saxons in the North were known. One can think that the newcomers could be supposed to go to their compatriots, or the very existence of these settlements gave rise to the legend of New England somewhere in Crimea and on the Caucasian coast. As proof of the legend, several toponyms are given on the Venetian portolan of 1553 and other old maps. It is more clearly spoken about Londia (Londina), the name of which is associated with London, and there are no other toponyms on the portolan. On it, all the names are not local, but Italian and there is no trace of any Chechen or Kurdish ones, although they should have already existed (see Pechenegs and Magyars, Cimmerians in Eastern European History). This raises doubts about the use of the names of the indicated maps by the population. The name of Londia was supposed to be a derivative of it. lontano “far away”. It really was far from the main Genoese port of Kaffa in Crimea. Thus, without denying the existence of New England, we must add some clarification to the legend.