The Areas of the Uprising of the Tocharian, Albanian, Thracian, Phrygian Languages.

The common territory of the Indo-Europeans in Eastern Europe was determined using the graphic-analytical method and its location was confirmed by the discovered linguistic and cultural connections of the Indo-Europeans with the Turks and Finno-Ugrians [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 42-44, 54-59]. In the resulting graphical model of the relationship of Indo-European languages, which made it possible to localize this territory on the map, there were no areas for the Illyrian, Tocharian, Phrygian and Thracian languages due to the lack of enough lexical material. There are free ethno-forming areas on the common Indo-European territory. We can try to place on these areas languages that are absent on the scheme using indirect methods. Let's start with the Tocharian language. Many researchers believed that the ancient area of the Tocharian habitat should have been somewhere near the settlements of the Greeks, Balts, Germans. So believed, for example, Krause:

In any case, it is clear that the ancestors of the Central Asian Tokhars had linguistic connections with both the Indo-European tribes of the southern group and the Baltic tribes [KRAUSE V. 1959: 157].

Many scholars believed approximately the same [GORNUNG B.V., 1963, 25, 80; GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V., 1984, 424], but more accurately, though not entirely, the Tocharian area was determined by W. Porzig:

The Tocharian language, of course, is adjacent to this group of languages (German-Baltic-Slavic – VS). It is characteristic that common phenomena unite the Tochar language with the Baltic and Slavic languages and at the same time a part of these phenomena connects all three languages with the West, and another part with the East does. In addition, there are special connections of Tocharian with the Germanic languages and at the same time with Greek, to which Baltic and Slavic have no relation… In such a way the relative and absolute coordinates of the place of the origin of Tocharian are determined so: it is located near the German-Baltic-Slavic space in the basin of rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea [PORZIG W. 1964: 315-316].

The conclusion about the Tocharian area "in the region of rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea" is made on the basis of the salmon argument, which is well-known among linguists. "Salmon is a fish that spawns in the river of the Baltic basin. The words related to the Germanic, Baltic and Slavic words which means “salmon” are present in Tocharian but it is absent in the other Indo-European languages. There is a vacant area on the map between the Berezina and Dnepr Rivers close to the rivers of the Baltic basin that matches all the requirements. The Tocharian habitat can be placed only here. According to the calculation, the number of common words in Tocharian and Greek is 146, and in Tocharian and Germanic – 145, in Tocharian and Baltic – 121, in Tocharian and Indo-Aryan – 118. The number of common words in Tocharian and other Indo-European languages is considerably less, for example, the Slavic languages have only 87 words related to Tocharian, but, as we can see, the Slavs were not neighbors of the Tocharians. The languages of the neighbors – the Balts, Indo-Aryans, and Greeks really have the most common words with Tocharian. True, Germanic languages have also a lot of common words with Tocharian, they should have been a little less. The explanation for this fact may be that the majority of etymological dictionaries were compiled by German scientists, and of course, they gave more examples from Germanic languages.

For large numbers, such errors are imperceptible, but in this case, trying to find more matches to the Tocharian words, the error has a noticeable value. However, there are other evidences in favor of just such placement of the Tokharian language area.

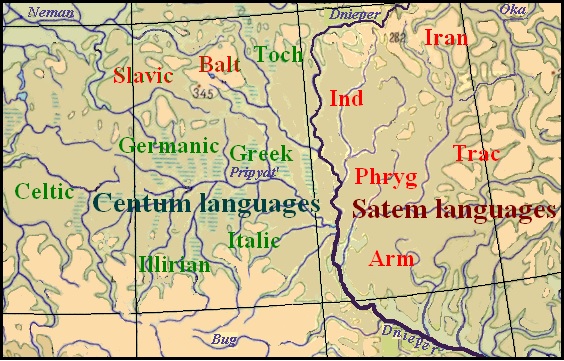

Right: The map of the Indo-European habitats located according the graphical model.

And now about the Albanian language. Authorities have different opinions about its origin. The reason for this is the significant impact of foreign languages, particularly affected Albanian vocabulary (ZHUGRA A.V., SYTOV A.P. 1990: 64). Some scientists believe that Albanian is a direct continuation of the Thracian language others think that it is offspring of Illyrian or it is a descendant of one of the "Paleo-Balkan languages" (LINDSTEDT JOUKO, 2014, 168-183). Agnia Desnitskaya supported the Illyrian hypothesis (DESNITSKAYA A.V.1966: 4), although supposed that this problem will be never solved by linguists completely. (DESNITSKAJA A.V. 1984: 727). The phonetic correspondences between the individual Illyrian lexemes and the words of the modern Albanian language "or have (because of the scarcity of material) too general character.., or can be hardly uniquely determined". (ZHUGRA A.V., SYTOV A.P., 1990: 68).

W. Porzig considered Albanian being an individual language on a par with the other Indo-European languages, including the Illyrian and Thracian (PORZIG W. 1964: 223). Such divergence of notions is caused by the extremely poor and random lexical material from the Illyrian and Thracian languages, as well as by the large number of loan-words in Albanian from Greek, Latin, Slavic, and other languages. R. Troutman presented such data of G. Meyer about the composition of the Albanian language: out of 5110 Albanian words, 1420 words have Romance origin, Slavic origin have 540 words, Turkish -1180, Modern Greek – 840, Indo-European heritage – 400 words and 730 words have an unknown origin. [TRAUTMAN REINHOLD. 1948.]

This variegated vocabulary impedes the establishment of family relations of the Albanian language. To establish them, let us again turn to the lexical-statistical data on which the model of the kinship of Indo-European languages was constructed. The Albanian language has the greatest number of common words with Greek (without taking into account the common Indo-European lexical stock), that are 167 words, farther follow 152 common words with German, 146 ones with Baltic, 131 with Italic, 128 with Iranian, 111 with Indo-Aryan, 76 with Armenian, etc. Similar calculations were made by Polish linguist Witold Mańczak. He compiled a table dictionary for comparison of the texts of the New Testament (Luke II-IV and John V-VI) in the Albanian, Polish, Italian, Greek, German and Lithuanian languages and counted word matches of Albanian and other languages. The results were as follows: Polish – 184, Italian – 167, Greek – 127, German – 97, Lithuanian and – 96 matches [MAŃCZAK WITOLD. 1987: 111-115]. As you can see, there are significant inconsistencies in the data. First of all, striking is a large number of similarities between the Albanian and Polish languages, which Mańczak presented as Slavic. At the same time, Ivan Duridanov, who carried out the Thracian-Dacian study, pointed out that Slavic-Thracian and Slavic-Dacian language connections don't appear [A. DURIDANOV IVAN, 1969: 100]. As we will see, the Albanian language genetically traced from Thracian, so the contradiction in Duridanov's and Mańczak's data must have an explanation. Mańczak took to the study the modern Albanian language which has many loan words from Slavic, while ancient lexical fund, which we used according to etymological dictionaries, has very few matches between the Albanian and Slavic languages. Compared to this, the Thracian and Dacian material used by Duridanov applies to much earlier times. The rest of the contradictions are explained by the complex development of the Albanian language.

Eric Hamp (1920-2019), who devoted his whole life to studying the relationship of the Albanian language with other Indo-European languages, acquainting readers with the historiography of the issue, came to the disappointing conclusion that the Albanian language as a whole will remain a closed book to the scholarly world (HAMP ERIS P. 1972: 1628). Both by phonological phenomena and by lexical and statistical data, it is impossible to localize the place of formation of the Proto-Albanian language, since there is no such area in the entire Indo-European territory, the position of which could be determined taking into account all the connections of the Albanian language with others.. For example, if this area would be near the areas of Greek and Italic languages, then the Albanian language had to have much more common words with Armenian, but they are few. Nevertheless, these data can be used. We will refer to them more than once. First, we pay attention that the Albanian language has much more common words with the Iranian language than with Indo-Aryan. This can mean that the area of arising of the Albanian language was lying closer to the Iranian area than to area of the Indo-Aryan language. In this case, it could not be located on the west and southwest of the Indo-Aryan area, but only to the east or south of the area of the Iranian language. The territory to the east of this area was already occupied by the Western branch of the Finnish people, just by the Veps and Mordvinic speakers. The “empty” area remains to the south of the Iranian one between the Desna and Seym Rivers. If the Proto-Albanian language was arisen in this area, it would have some common words with the Modvinic languages Erzia and Moksha, which ancestors were nearest neighbours of this land. Even cursory comparative analysis of the vocabulary of the Albanian, Moksha and Erzya languages indeed gave immediately results. Here are some examples of Albanian-Mordovian lexical matches which often have close analogues in other neighboring languages:

Alb. bizele “peas” – Mok., Erz. pizёl “berries of mountain ash”;

Alb. bretkosё “frog” – Mok. vatraksh “frog” (Greek βατραχοσ “frog”, Rom broasca "frog" as possible spoiled Thracian substratum) etc.

Alb. dobёt “quiet” – Mok. topafks “satiety”, Erz topafty “sated” (Mari typ “quiet”);

Alb. enё “a vessel” – Mok. en’a “a scoop”;

Alb. kapёrdij “to swallow” – Mok. kapordams “to swallow”, Erz. koporks “to swallow”;

Alb. kofšё “thigh” – Erz. kačo “thigh”, Mok. kače "ankle";

Alb. keqe “evil” – Mok., Erz. k’až “evil”;

Alb. rroj "to live" – Mok., Erz. er’ams "to live".

Alb. tani “today” – Mok. t’ani “now” (Mari tenij “today”, Fin. tänään, Est täna “today”;

Alb. turi “muzzle” – Mok, Erz trva “a lip” (Mari t’arvö “a lip”);

Alb zhavor “gravel” – Mok šuvar “sand” (this word in several different forms was spread in the Baltic and Slavic languages).

Above examples are enough to recognize that the ancient Albanian-Mordvinic connections were real and therefore allow us to locate with a high probability the area of formation of the Albanian language just between the Desna and Seym Rivers. But then how do we explain the fact that the Albanian language has the most common words with the Greek, Germanic, and Baltic languages? As we shall see, this is the result of later borrowing after the first stage of resettlement of Indo-European tribes.

Very few lexical data are available for the localization of the Urheimat of the Illyrians, but, according to the other language facts, Walter Porzig found arguments to claim that Illyrian and Celtic areas were adjacent in early history [PORZIG W. 1964: 159]. He also indicated that “Illyrian and Greek have remarkably few mutual connections though both peoples lived in permanent proximity since the time of Illyrian migration.” [Ibid: 224]. If we conjecture the Illyrian area to be near the Celtic and far from the Greek ones, we can find some additional data to prove the location of the Illyrian area somewhere on the West Indo-European territory. Place names can be very helpful in this case. The Illyrian toponymy was studied by the linguist Oleg Trubachiov and the archaeologist Dmitriy Telegin. Pointing out at the relative vicinity of the Celtic and Illyrian onomastics in general, Trubachiov wrote: "…hydronyms with West-Balkan connections are concentrated on the Dnestr narrow space and are sporadic present to the north in the Goryn’ River's basin and to the north-east in the catchment of the river Teterev river". [TRUBACHIOV O.N. 1968: 279]. Such hydronyms as Barbara, Goryn, Grana, Dupa, Ikva, Ipatva, Lukva are considered by Trybacgiov to be the Illyrian. D. Telegin confirms Trubachiov's idea and specifies that the Illyrian (Celtic-Illyrian) hydronyms make three concentrations in Ukraine: the Kyiv, Zhytomyr and Upper Dnestr accumulations. When the first two of them have only ten names, the last one has almost 30 names [TElEGIN D.Ya. 1990-1]. Thus we have reason to believe that Illyrian people resided in the Upper Dnestr river's basin and populated the territory to the north at a certain period. In this case, their ancestral home should be placed on the space between the Sluch, West Bug, and Pripyat’ rivers, so called Volhynia.

Until now reliable interpretation of the word Volhynia absent. The search could be unsuccessful, because it has an Illyrian origin, and no such assumption has arisen. If you try to find the connection of this word with the Northern Balkan language range, you can find Dalmatian tribal names Bulini, Buliones and place name Tribulium which have Illyrian origin. So V.P. Yaylenko belives and indicates that Gr. φῡλή (phylë) "kin, tribe" has correspondence only in Illyrian and precisely in the indicated words (YAYLENKO V.P. 1990: 9-10). The apparent consonance of these words with the name Volhynia gives reason to associate it with some Illyrian tribe that once populated this area.

A smaller amount of hydronyms of possible Illyrian origin in Volyn compared to the region of the Upper Dniester basin may indicate that people began call rivers only at a certain stage of their development or after they were convinced that there were many rivers in the world. Until that time, the nearest river could be just a “river” without additional identification. At one time, Jan Chekanovsky defined the original homeland of the Illyrians as follows:

The first ancestral home of the Illyrians should be considered Moravia, Western Slovakia, Silesia, and the surrounding region. In this area, there are numerous geographical names that can be associated with the names available in the spaces occupied later by Illyrians and Veneti. These are such names as Odra, Sava, Drava, Morava, Opava [CZEKANOWSKI JAN. 1957: 99].

A similar idea was expressed by Yu. Pokorny (POKORNY JULIUS. 1936: 193). However, river names ending in -ava may be of Kurdish origin (-ava is the ezafe form of -av "water, river"). Therefore, the assumption about the ancestral home of the Illyrians in Slovakia must be discarded.

The Urheimat of the Phrygians was to be close to the Greek and Armenian areas because the vicinity of the Phrygians to the Greeks and the Armenians is confirmed by numerous linguistic data. For example, Gamkrelidze and Ivanov wrote: “Phrygian language… has structural features that bring it close to the dialects of Greek-Armenian area” [GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984: 910]. Armenian scholar Gr. Kapantsyan indicated that Greek annalists (Herodotus, Eudoksus, and others) were writing about the vicinity of Phrygians and Armenians. ”Phrygians and Armenians were together under the same banners in the army of Xerxes and they were dressed and armed identically” [KAPANTSIAN GR. 1956: 164]. Russian scholar T. Moisejeva also wrote about the closeness of Phrygian to Greek and Armenian [MOISEYEVA T.A. 1986: 13]. At the same time, the area of the formation of the Phrygian language should have been close to the Thracian language, since these two languages according to the schemes of Hirt and Ler-Splavinsky are also closely related. The latest developments allow us to speak about the place of the Phrygian language among the Indo-European more confidently. After analyzing the explicit data on the phonetics and morphology of the Phrygian language, F. Cortlandt comes to the following conclusion:

… Greek, Phrygian, and Thraco-Armenian reflect a single Indo-European dialect area that was divided by two major isoglosses, viz. the devoicing of the glottalic stops which separated Phrygian from Greek and the satǝmization of the palatovelars which separated it from Thraco-Armenian. Phrygian provides in several respects the missing link between Greek and Armenian [KORTLANDT FREDERIK. 2016: 6].

Under these conditions, the place of the formation of the Phrygian is most suitable for the area between the Desna and Iput Rivers, south of the area of the Indo-Aryan language (see the map at right). If such an arrangement corresponds to reality, then the Phrygian language should also have close relations with the Indo-Aryan language, however, checking this is prevented by the scarcity of the available Phrygian lexical material. However, F. Cortlandt gives some examples of correspondences between Phrygian and Indo-Iranian languages [ibid].

The number of common Hittite-Luwian words with other Indo-European languages suggests that the area of its formation should be located somewhere between the areas of Greek, Armenian, and Italic languages. Common matches for Hittite, excluding common Indo-European roots, found in the Greek – 106. Slightly less in the Armenian – 102, a significant portion of which was included in the table according to Kapantsyan [KAPANTSYAN Gr., 1956], which gives a lot of Armenian-Hittite parallels that are not present in the etymological dictionary of Pokorny. 86 matches were found as in the Italic and in Germanic languages. According to these data, the area of formation of Hittite could be located in the triangle between the Dnieper, Teteriv, and Ros Rivers, i.e. on the part of Tripilla culture. But the main argument for this decision was the common reasoning. The boundaries of the territory of the settlement of any ethnic group should not look like a broken line, that is, the area should not have distinct bulges and concave, otherwise the inhabitants of these places should be assimilated or pushed out by non-native neighbors.

However, there are reasons to believe that the ancestors of the Hittites never were present in Eastern Europe and were a part of the Indo-Europeans which remained at the site of the original settlement, and later they spread almost all over Asia Minor. This opinion was suggested to me by Peter de Rijk (the Netherlands) with reference to Alvin Kloekhorst which stated:

The Anatolian branch can be shown to have been the first to split off from Proto-Indo-European because several instances can be identified in which Hittite shows an original situation where all other Indo-European languages have undergone a common innovation. This means… the ancestors of the speakers of the non-Anatolian Indo-European languages shared a period of common innovations that no longer reached the ancestors of the speakers of Proto-Anatolian [KLOEKHRORST ALWIN, 2008, 88].

To go along with this idea, there are good reasons and they are given by Alvin Kloekhorst, but this difference of the Hittite language from the rest of Indo-European has long been noted, especially by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov [GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984, 395]. First, a small number of Hittite words, which have matches in the other Indo-European languages are striking. The Indo-European origin of Hittites is most evidenced by grammatical forms:

… Hittite root-words have in most non-Indo-European origin, only ten percent of them originated from PIE, while the forms of declension and conjugation, as well as forming new word are distinctly Indo-European, although there are also representatives and morphological forms of Asia Minor (Asiatic) (KAPANTSYAN Gr., 1956, 79).

Obviously, the words of Indo-European origin are the oldest in the Hittite language therefore they are important for historical-linguistic analysis. But the grammatical forms, which are different from the Indo-European, can be both archaic and arisen at the time when the bulk of the Indo-Europeans migrated to Eastern Europe. The timing of their occurrence may be a good material for a general history of the development of language grammatical structure.

Therefore, under such circumstances, it must be assumed that the area between the Dnieper, Teteriv, and Ros' Rivers was populated by some other Indo-European tribe, for example, by the Thracians. Some researchers, in particular, D. Telegin argue that the greatest concentration of Thracian (Daco-Thracian) hydronyms can be found in the basins of the Southern Bug, Ros', Teteriv, (Ibr, Yantra, Alta, etc.) (TELEGIN D. Y, 1990-1). I. Zhelezniak had the same reflection (ZHELEZNIAK I. M, 1987). However by the time when Thracian language arose, the area near these rivers could not be hold by the Thracians, because, in this case, they should have been the first of the Indo-Europeans who start moving southward, but this could not be. Usually, people in their migrations adhere to the order, which is determined by their places of previous settlements. If the Thracians later occupied the territory north of the Greeks, their ancestral home could not be in the south of Greek one. Obviously mentioned area was populated by some Indo-European tribe, whose descendants are lost in history without a trace.

After such placement of areas of Indo-European languages it appears that the Thracian language has no free area at all. Since it is close to Phrygian and Albanian is the successor of Illyrian or Thracian, then there is no choice but to place the Thracian area where we placed the ancestors of the Albanians, ie to consider Albanian as a continuation of Thracian. This area is bordered by the Desna River and its left tributary of the Nerussa in the west and north, and in the south and east by the Seym River and its right tributary Svapa.

Having the areas of the uprising of the Tocharian, Albanian, Thracian, Phrygian languages we can construct the whole map of the Indo-Europeans territory.

|

The common territory of the settlement of Indo-European in the Dnepr basin

Below the same in GoogleMap.

View Indo-European in a larger map