Ethnicity of the Archaeological Cultures of East Europe in the XX – XII Centuries BC.

The migration of Turkic people in different directions lasted several centuries, during that time some of them remained in a large space between the Volga River and the Carpathians. They became the creators of the Catacomb culture (2000 – 1600 BC) based on the Pit one, which had to be some Turkic tribes who stayed near the site of the Urheimat. It could be the Oghuzes, Seljuks, Turkmens, Kipchaks, and the Volga Tatars, occupied the westernmost areas of the common Turkic space between the Dnieper and the Don (see the section The Turkic Tribes).

Development of the Pit culture in Catacomb one is testified by some archaeological finds, in particular, by the Vlasovka burial (the village of Vlasovka within the Gribanov district of Voronezh Region):

… As the Pit burial, and the burial of the Catacomb type do not show the chronological gap, but determine the character of the burial place as a "working moment" of the process of continuity and interaction [SINIUK A.T., 1969: 56].

Catacomb cultural-historical community occuried in steppe and forest-steppe zones of the Northern Pontic region from the For-Caucasus and the Volga River till the lower Danube River. Ukrainian experts share catacomb historical community on such culture:

1. Kharkov-Voronezh

2. Donetsk,

3. Ingul,

4. For-Ciscaucasian,

5. Poltavka.

The first four cultures may belong to the Oghuzes, Seljuks, Turkmens, and Kipchaks, the Poltavka culture could be created by the related Nogai and Kazakh tribes.

At this time, some part of the Turks remained in Right-Bank Ukraine, the bulk of whom migrated to Central and Northern Europe. They were to become the creators of the Middle Dnieper culture, which existed from the end of the third to the middle of the second millennium BC. It is part of the Corded Ware cultures, the creators of which were, as we know, the Turkic people, and its most ancient sites are concentrated in the area limited by the Dnieper, Teterev, and Ros rivers, which was previously part of the Trypillian culture. There are several place names here of Turkic origin if we interpret them using the Chuvash language, which more than other Turkic languages has preserved the features of the Proto-Turkic. This feature has its explanation. While the Turkic majority migrated in different directions to Central Europe and Scandinavia and subsequently assimilated among other peoples, the Turkic tribe who stayed in Western Ukraine retained their ethnicity. In the first millennium BC, they settled over a wide area of Eastern and Central Europe and became known in history as the Scythians. Some Scythians were the ancestors of the modern Chuvashes, so those Turks who originally inhabited Western Ukraine are called Protochivashes.

Examples of Turkic toponyms in the indicated area are given below. However, for some of them, there are correspondences in other places of settlement of Turks. Cf.:

Boyarka, a town in Kyiv Region, a locality in the city of Rivne, two villages in Cherkasy and Odesa Region – Chuv. payăr "proper, own"; pay "a part" ăru "tribe, kin, progeny".

Kaharlyk, a town in Kyiv Region and two villages in Kirovohrad and Odesa Regions – Chuv. kăkar "to join", and the formant -lyk refers to one of two Chuvash suffixes –lăk or –lăkh, which can form adjectives or give an abstract value or result of the action.

Kodaky, a village in Kyiv Region (previously Kaydaky) – Chuv. kay "to grow, develop", tăkă "rich, abundant".

Uzyn, two villages in Kiev and Ivano-Frankivsk Regions – Chuv. uççăn "open, free, light".

Ulashivka, a village in Kiev Region – Chuv ulăsh "change", "to change".

Other options of CWC were Fatyanovo and Balanovo cultures in the Upper Volga basin. Ukrainian experts believe that ca. 3200—2300 BC. Fatyanovo people came into the Volga basin along the Desna River, from the territory of the later Middle Dnieper culture sites:

I. Artemenko's research of cemeteries in the Desna basin and D. Krainov's allocation earliest sites in the Moscow-Klyazma group suggest that this culture has developed as a result of moving a part of the population of the Middle Dnieper culture to this territory at the beginning of its middle stages – in the end of the 3rd – beginning of the 2nd II mill. BC [Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Tom 1. Pervobytnaya arkheologiya. 1985: 375].

This idea is also shared by some Russian scientists. On the other hand, the earliest sites of Fatyanovo culture are concentrated in the southwestern part of the whole Fatyanovo territory in the upper Moskva River (KRENKE N.A. 2014, 14, fig. 6)

Thus, there is reason to believe that a Turkic tribe, simultaneously assimilating the local population, moved along the Desna, Seym, and further along the Oka River, that is, between the settlements of the Indo-European and Finno-Ugric peoples, and reached the Klyaz'ma basin. They settled in a nearby locality creating here Fatyanovo culture. The sites of CWC, except the Western Bug basin, are absent on the territory occupied by the Indo-Europeans. Obviously, there was in the Dnieper basin no empty space for settling Turks. The movement of Turkic people toward the Volga River, which was to last for several decades, is marked by place names of Turkic origin stretching as a band from Kiev to Moscow:

Basan', villages Old Basan' and New Basan' in Chernihiv Region and the village of Basan' in Zaporizhzhia Region – Chuv. pusă «corn field», ăn "to come up well".

Tabaivka, a village in Chernihiv Region – Chuv. tap «to press, push», ăyă «a chisel».

Uday, a river, rt of the Sula River, lt of the Dnieper snd the village of Uday on it. This place name as similar to it are very wide disseminated from the Carpathians till the Oka River (a few villages Odaiv, Odai, Odaya, the town of Odoyev and others) – Chuv ută 1. «hay». 2. «island». 3. «valley». 4. "grove" і ay «low, lowlands».

Bakhmach,a town in Chernihiv Region – Chuv păkh «to see, look» and măch «blinking, winking».

Samara, a village in Sumy Region – Chuv samăr «fat, plump».

Kuyanivka, a village in Sumy Region – Chuv kuyan «a hare».

Tolpinka, a river, rt of the Seym River, lt of the Desna river, lt of the Dnieper River and a village on it, the village of Tolpino in Tver Region, Russia – Chuc talpăn «to gush, spurt, flow rapidly».

Kurdiumovka, a village in Sumy Region and a town in Dnetsk Region – Chuv khurt "worm, caterpillar", yum "fortune-telling, sorcery"

Adoyeva, a village in Kursk Region, Russia – see Uday

Voronizh, a village in Sumy Region – var «valley», anăsh «width».

Yampol, a town in Sumy Region – Chuv. yam "manufacturing of tar", păl "chimney".

Apazha, a town in Sumy Region – Chuv. apa «a wife», shaw «nois, shout».

Kokorevka, a town in Briansk Region, Russia – Chuv. kăkăr «breast, chest».

Shablykino, a town in Orel Region,, two villages in Moscow Region, and villages in Tver, Kostroma, Vladimir Region – Chuv. shapălkka «a chatterbox».

Bolkhov, a town in Orel Region, Russia – Chuv pulăkh «fertility».

Kozelsk, a town in Kaluga Region, Russia – Chuv. kĕçĕllĕ «ill of itch, scab».

Odoyev, a town in Tula Region, Russia – see Uday.

Shatovo, villages in Tula and Voscow Regions – Chuv. shat "tight", "thickly".

Bolokhovo, a town in Tula Region, Russia – see Bolkhov

Tarusa (Torusa), a town in Kaluga Region, Russia – Chuv tărăs "box of birch bark".

Serpukhov, a city in Moscow Region – Chuv sĕr «to rub», to rub «hobble».

The presence of a Turkic tribe on the territory of Fatyanovo is directly told by the names of the settlements of Chausovo in the Smolensk and Kaluga regions, Chausy in the Bryansk and Mogilyov regions, because the self-name of Chuvash is chăvash. Moreover, among all the enigmatical place names of Russia, one of the most frequent is the name Akulovo (35 cases) and its variant Okulovo (20 cases). Chuv.aka "arable land, plowing" suits well for decoding this name. Decorated with an affix – la, the root forms an adjective with an equivalent meaning. There is also a verb akala "to plow" in Chuvash. Such names are fit for new settlements that have been given by the agricultural population from the forest-steppe zone searching for vacant land. Taking into account also the names Akulino, Akulovka, and others, then there are more than sixty settlements of this type mainly in the northern regions north-west of the Tula-Nizhny Novgorod line. Most place names Akulovo are present in the Moscow region (12 villages).

The Turkic toponymy prevails in the western part of the Fatyanovo culture area. Further to the east, where it merges with Balanovo culture, the names of the possible Turkic origin are less. Therefore it can be assumed that the creators of the Balanovo culture were some other Turkic tribes. The Turkic origin is hidden in another common place name Yam. There are more than ten such names in the Tver Region and adjacent areas. This concentration gives reason to think that this name comes not from the Russian word yam "post station", which has Old English origins from OE hām "house, dwelling", "hearth" (more details in the section Opening of the Great Siberian Route). These toponyms did not stretch out in lines along the communication routes, as one might expect, so one might think that they can be associated with Chuv. yam "smoking, a distillation of tar". We also find this root in the place names of Yampol, which are widespread in a large area in the places of the Turkic settlement. Chuvash place names are often tried to decipher unsuccessfully with the help of Finno-Ugric languages. For example, decrypting the appellate nerl', which gives names for two settlements and two rivers, is more believable not "Finno-Ugric" ner, whose traces were not found in dictionaries, but Chuv. nĕrlĕ "beautiful". Other examples may be the following:

Orsha, towns in Vitebsk and Kalinin Regions, villages in Novorzhev district of Pskov Region and Kalinin district of Kalinin Region – чув ărsha "darkness, mirage".

Boldyrevo, four villages in Vesiegonsk, Vyshnevolotsk, Kesovogorsk and Staritsa districts of Tver Region and a village in Yaroslavl district of Yaroslavl Region – Chuv. păltăr "entrance-hall, closet".

Kostroma, region center – Chuv. kăstărma "whirligig, peg-top".

Shevardino, a village in Moscow Region – Chuv shĕvĕrt "to sharp".

Cherkasy, a former village, now a part of the city of Tver – Chuv. kasă "a street, village" (izafet kassi).

Tolpygino, villages in Yaroskav, Ivanovo Regions, the Tovpyzhyn in Rivne Region (Ukraine), the village of Tolpygi in Smolensk Region – Chuv talpăp «to gush, spurt, flow rapidly», ekki "nature". See Tolpinka.

Bernovo, a lake south-east of the city of Tver – pĕrne "a basket".

The last name has an analog in Belarus, where Lake Bernovo is located too. There are ner it settlements Zhurzhava, Uhl', which also can have Turkic origin. If there are here any CWC sites is still unknown. But this question is important to more accurately determine the genesis of Fatyanovo culture.

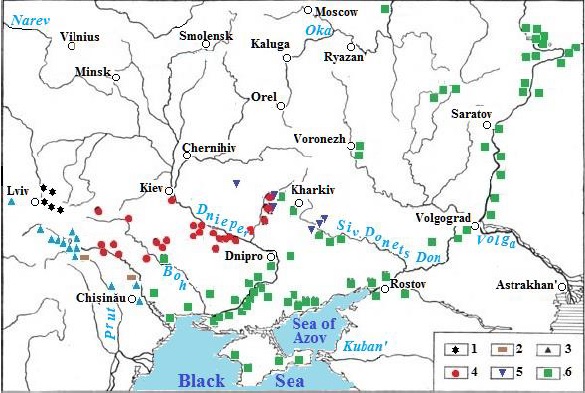

Right: Archaeological cultures and ethnic groups in Eastern Europe since the end of the third to the middle of the second millennium BC.

The question of the creators of Balanovo culture remains open. We think these were Turkic tribes that moved from the lower Don up the Volga River. The ethnicity of the Volga toponymy was not considered, because its stratigraphy is impossible for the constant presence of the Turks in the Volga region, who can be correlated with the Volga Tatars.

Based on different variants of the CWC, several related cultures arose and spread across a large area north of the Carpathians from the Oder in the west and to the Oka River in the east, generally belonging to the Trzciniec range of cultures (TRC). Ukrainian archaeologists include in this circle, in addition to the Trzciniec culture in the narrow sense that is common in Poland and Volyn, also the Komariv culture in the upper Dniester and the Sosnitsia culture, which replaced the Middle Dnieper one. The similarity of these cultures is caused by their common origin, but in the ethnic sense they were different.

We know that the ancient Germanic people occupied the territory from the Vistula River to the Dnieper on both sides of Pripyat River. At the same time, the Teutons who inhabited Volyn were the creators of the local version of the Trzciniec culture, and the Anglo-Saxons, migrating from their ancestral homeland in the area between the Pripyat, Teterev, and Sluch Rivers, became the creators of the Sosnitsa culture. Given the stop of the Turkic people during moving to Central Europe, witnessed by toponymy in Western Ukraine, they were the creators of the Komariv culture. The Turkic tribe remained on the territory of Western Ukraine until the arrival of the Slavs here, as evidenced by similar motifs in the folk cultures of the Chuvash and Ukrainians. Developing the traditions of the Komariv culture, the Turkic people eventually became the creators of the Vysotska culture (11–7th century BC), although there is an opinion about its origin under the influence of the culture of the Thracian Hallstatt (Gava-Holigrady). M. Peleschishin, an investigator of the Vysotsky culture, refuted this view, believing that it is not a “mixed, hybrid phenomenon that arose at the junction of several different cultures of origin”, but, on the contrary, has local roots:

Its local origin was an important ethno-cultural phenomenon, selectively borrowing some elements from neighboring cultures [PELESHCHYSHYN MYKOLA, 1998, 30].

The carriers of the Noua, Gava-Holigrady, Koziya and other cultures could not have a significant impact on the development of TRC, since they did not advance to the productive lands of Transnistria east of Zbruch and north of the Prut basin. The reason for this was significant obstacles that prevented them from doing so. We can only assume that this space was inhabited by a rather strong, conservative in its traditions tribe, which, using the natural conditions – the hard-to-reach canyons of the Podolian rivers – did not allow strangers to their lands [KRUSHELNYTSKA, 1998, 193].

Many archaeologists agree that Chernolis culture developed on the basis of Belogrudovo one, which existed in the 12-11 cen. BC. Presumably the creators of this culture were a part of the Thracians, who stopped in the Uman region while their movement to the Balkans. (See the section "The migration of the Indo-European Peoples at the End of the 2nd and at the Beginning of the 1st Mill BC"). On the other hand, L. Krushelnytska repeatedly pointed out in her works that the Chernolis culture had some specific features that connect it with Vysotska one [ibid], what can be explained by the migration of carriers of the latter eastward. This assumption is confirmed by the fact that the number of sites of the Vysotska culture is much smaller compared with the Komariv one, which lay on its basis. The use of radiocarbon analysis allows tracing the transformation of other TRC variants.:

The East area of TRC (Sosnotsa culture – V.S.) can be generally dated to the period of 1700 – 1000 years BC. After 1300 BC Komariv Group TCR in the Dnister region is gradually replaced by the culture of Noah. Residual effects of TCR are preserved longest in the form of sites of Bilogrudiv and Lebediv types in the forest-steppe of the South Bug and the Middle Dnieper basins. Remnants of TCR on Middle Dnieper are largely preserved in the Chornolis culture of the transition period [LYSENKO S.D., 2005: 60].

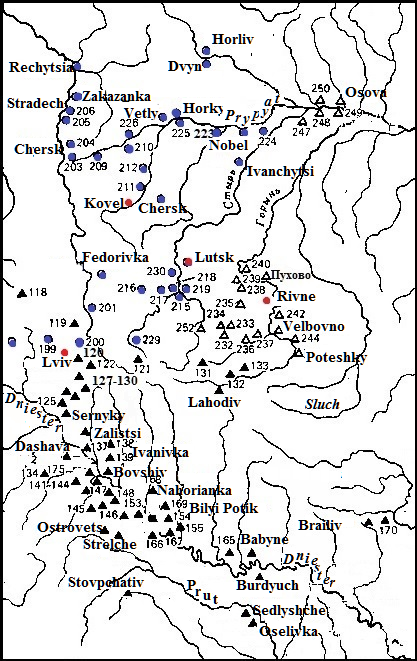

At right: The spread of sites of Trzciniec and Komariv cultures

A fragment of the map in Archaeology site.

On the map, the sites of Trzciniec culture (created by the Teutons) are indicated by blue dots. The sites of the Komariv culture are marked with black triangles. The contact area between the Trzciniec and Sosnitsa cultures (created by the Anglo-Saxons) are indicated by light triangles.

Appeared in the Anglo-Saxon area, the Sosnitska culture was moving up to the Ros' River and then its sites stretch as a narrow strip along the Dnieper, which is also confirmed by the toponymy data of Germanic origin (see the section "Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe.). Obviously, namely the Anglo-Saxons pushed out the Thracians from the area between the Teteriv, the Dnieper, and the Ros' Rivers.

South of the Thracians, the Armenians and Thracians who had moved here from the left bank of the Dnieper under pressure of the Iranians were supposed to reside in the northern Black Sea coast. Over time, most of them turned out to be in Asia Minor, but their part could remain in place, becoming the creators of the Sabatinovka culture, which, under the influence of the Thracians arriving from the north, was replaced by the Belozero culture (XII — X century BC). Migration of Armenians and Phrygians to Asia Minor from the Northern Black Sea Region is confirmed by the findings of the experts:

The study of the material culture of Mycenaean Greece and Sabatinovka culture (XV-XIII cc. BC), from which Bilozersk culture was developed, indicates the presence of fairly close ties between the population of the Northern Black Sea Shore and Eastern Middle Mediterranean at that time [CHERNIAKOV I.N. 2010: 118].

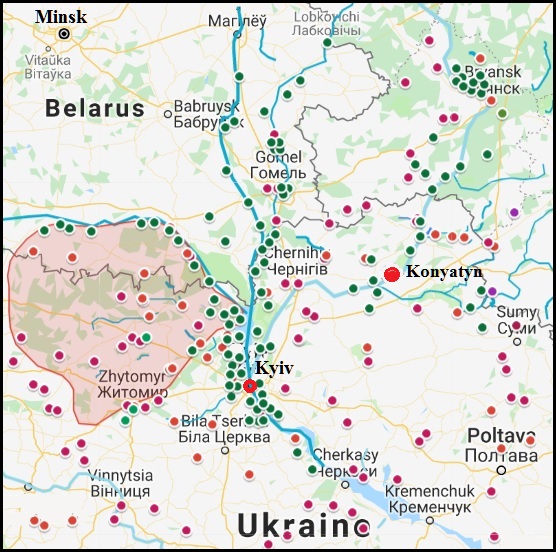

At left: The spread of sites of Sosnitsa culture

A fragment of the map in Archaeology site

The map also shows several sites of the Bondarikha culture and the village of Konyatin, whose name is decoded by Old English as "Royal Town" (see Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe. ).

Later, the Anglo-Saxons moved from the right to the left bank of the Dnieper in the Iranian region north of the Lower Desna and in the Sozh basin, i.e., in the areas of Proto-Sssets and Sogdians. This is confirmed by local toponyms, which can be expanded using Old English (Bryansk, Boryatino, Ivot, Konotop, Resta, Sozh, Khotynets, etc.)

The proximity of the Germanic tribes with the Finnish ones of the Maryanovka and later Bondarikha cultures is confirmed by the enigmatic traces of the Finno-Germanic language connections, most of all reflected in the biological nomenclature, in particular, in the names of trees and fish, which are explained as follows:

… some of the groups of bearers of Proto-Finnic and bearers of disintegrating Proto-Germanic, respectively Proto-East-Germanic and Proto-North-Germanic could have lived in the last century BC a half-nomadic life in close proximity on the vast space-continuum between the rivers Dnieper and Volga in the South-East up to the Vistula and Baltic Sea in the North-West [ROT SANDOR. 1990: 25].

However, it is believed that such contacts go in more ancient times [KOIVULEHTO JORMA. 1990, vol. 2, 9], which appears more believable in the light of the actual data.

Since the beginning of the 16th c. BC Zrubna (Carcass or Timber-grave, Srubnaya in Russian) culture began to develop between the rivers Dnieper and Don. Previously, the prevailing view was that this culture had no local roots, and appeared on the territory of the Ukraine in a ready form. It was extended from the lower Volga to the Dnieper (sites of the Zrubna culture on the right bank of the Dnieper are present only in the narrow bank strip), and a lot of remains is concentrated in the northern part of the Seversky Donets Basin. The carriers of this culture were sedentary farmers of the unusually high for that time level of economic development. Some scientists are looking for the roots of the Zrubna culture in the area of Poltavka culture in the catchment of the Volga and further to the east in the area of the Andronov culture [KUZ'MINA E.E. 1986: 188; BEREZANSKAYA S.S. 1986: 43; Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Tom 1. Pervobytnaya arkheologiya., 1985: 474]. Authoritatively about the origin of the Zrubna culture, wrote M. Artamonov:

Settling of the creators of the Zrubna culture on the steppe zone of Eastern Europe is regarded to the second half of the 2nd mill BC. Together with them, instead of arsenic bronze of North Caucasian origin, tin Uralic bronze spreads in the forms appearing together with Seima culture of the Kama and the Middle Volga regions.There is reason to believe that the Seima culture has developed as the result of the migration of some populations from Siberia… The rapid spread of the Zrubna culture, wich borrowed Siberian arms from the more advanced Seima cultures, on Northern Black Sea Country was accompanied by forcing out and by assimilation of the Catacomb culture with its version – tthe Multi-cordoned ware culture, ousted from the country between the Don and the Seversky Donets River to the lower currents of the Don and the Dnieper in the more former period. Around the 13th century BC the Zrubna culture is already resent on the Dniester River [ARTAMONOV M.I. 1974: 11].

Fig. 37. The archaeological Cultures in the basins of the Dnieper, Don and the Dniester in the XV – XII centuries. BC.

Such Artamonov’s thinking, obviously, was based on the opinion which had a place among the other scientists about permanent migration movement from east to west, in particular the so-called “Altaic” and "Uralic" peoples.

However, taking into account the localization of the ancestral homelands of these peoples in Eastern Europe, they could not move from the east, on the contrary, the Turkic peoples moved from Europe just to the east. In addition, the origin of the metallurgical province in the Volga region E.N. Chernykh connects with moving of ethnic groups from the Balkan-Carpathian region who brought their cultural and technological traditions to the Volga region [CHERNYKH Ye. N. 1976: 39] which casts doubt on the existence of a higher level of metallurgy in the Urals, than in more western regions.

Obviously, going out of similar positions, other scholars think that sufficient genetic basis for the Zrubna culture was absent in the Low abd Middle Volga basins and claim that the single center of origin of the Zrubna culture did nor exist, that is its uprising in each region should be explained in terms of local archaeological basis [CHEREDNICHENKO N.N. 1986:45]. It is important in this scientific dispute that the view of the coming creators of the Zrubna culture from the east is not certain, therefore it is reasonable to consider other options about its origin.

Sites of cultures of Pre-Scythian time in the south of Eastern Europe

Modified map out ofArchaeology site.

Legend: 1 – Vysotska culture, 2 – culture of Noua, 3 – culture of the Thracian Hallstatt, 4 – Belogrudov-Chernolis culture, 5 – Bondarikhinska culture, 6 – Zrubna culture.

The key to the origin of Zrubna culture lies in the similarity of the burials in the form of a timber carcass with burial structures in Mycenaean times in Greece. This resemblance was noticed by M. Cherednichenko while learning about objects so-called Bessarabian treasures and seeing in them elements of Mycenaean culture:

The similarity of the burial structures of the early Zrubna graves in large pits and shaft tombs at Mycenae have a certain interest. Shaft tombs were common ground pits within which boxes, covered with wooden beams, were been built. Flat stone slabs, or twigs, topped with a thin layer of waterproof clay were stacked on the boards [CHEREDNICHENKO N.N., 1986: 74].

For comparison, we can give a description of Zrubna burial structures:

A rectangular pit is under the burial mounds on the mainland. A wooden carcass, more precisely, a frame of oak, birch, or pine trees were placed in it… a layer of reeds or oak bark can be found on the bottom and the top of a log-ceiling [Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Tom 1., 1985: 466].

Assuming that the similarities between Zrubna and Mycenaean burial structures are not accidental, an attempt was made to find additional evidence of the possible participation of the ancient Greeks in forming the Zrubna culture, taking into account the results of the research made with using the graph-analytical method [SRETSYUK VALENTYN, 1998, 82-83]. Further studies only confirmed this possibility.

We have found facts that give reason to believe that the Greek settlers in Ukraine have not been assimilated by other nations for a long time, and lived with them in peaceful coexistence. Herodotus remembers an agricultural tribe of Callipidai in his History. He asserted they were Hellenic Scythians and inhabited the territory along the Hypanis River (Southern Bug) west of Borisphen (Dnieper). Obviously, the reason for Herodotus' belief in Callipidai as semi-Greeks could be given to their tongue, which developed from the common Greeks parent language, but to a certain extent different from the classical Greek after several centuries of its development in isolation from the majority of the Hellenes. Just they could be the ancestors of those Greeks, who stayed in Ukraine from ancient times.

On the other hand, Herodotus, describing the wooden town of Gelonos in the land of Budinoi, said that it was inhabited by Budinoi and Gelonians. Gelonos is associated with Bilsk hillfort on the Vorskla River and Budinoi are identified confidently by historians confidently with Mordvins that left many traces in the toponymy on the banks of the Vorskla, Sula, and Psel Rivers. Describing the inhabitants of Gelonos, Herodotus wrote: "…the Gelonians are originally Hellenes, and they removed from the trading stations on the coast and settled among the Budinoi; and they use partly the Scythian language and partly the Hellenic" [HERODOTUS. Book 4: 108].

The reasons for relocation could not exist, therefore because M.I. Artamonov, tying Gelonos with Bilski hillfort, pointed out that the reason for Herodotus identifying Gelonos residents with the Greeks was only harmony "Gelonians – Hellenes" [ARTAMONOV M.I., 1974: 93] and considered Gelonians as one of the Scythian tribes. However, there are also striking similarities between the Iranian ethnonym "Gilanian" with the name of the city of Gelonos and its inhabitants. Exploring the kinship of Iranian languages, we localized the area of the formation of Gilakilanguage lying between the upper the Seversky Donets and Oskol Rivers, which is adjacent to Gelonos [STETSYUK VALENTYN, 1998, 78]. Some Greek-Gilaki lexical parallels suggest the possibility of contact Gilanians with Greeks:

Gr. κορη "a girl" – Gil. kor"a girl";

Gr. δάμαρ "a wife", δαμάζω "to conquer, marry" – Gil. damad "a son-in-law";

Gr. ῥοή "stream, flowing" – Gil. rå "way, path";

Gr. γάμος "marriage, wedding" – Gil. hamser "husband, wife";

Gr. φανός "light" – Gil. fanus "latern".

In the Pre-Scythian times, all Iranian tribes occupied a large area between the Dnieper and Don Rivers, and other lexical coincidences between the Iranian and Greek languages may serve as evidence of the presence of the Greeks in these places during the II mill. BC. Some of these matches were found while researching. For example, Greek εσχαρα "hearth, fire" has parallels in the Iranian words meaning "bright": Pers ašekar, Gil ešêker, Kurd. aşkere, Yagn oškoro etc. Greek τιμωρεω "to protect" corresponds to Pers timar, Gil timer, Kurd tîmar, Tal tümo "care". Greek σασ "a moth" can be connected with Pers, Kurd sas "a bug", Gil. ses "id". Afg lamba "flame" was borrowed from Gr λαμπη "torch", "light", rawdəl "to suck" (Gr. ῥυφέω "to slurp, swallow") and Afg julaf "barley" could originate from Gr αλφι borrowed from Turk arpa "barley". Tal külos "a ship", "a trough" is similar to Gr γαελοσ "a bucket", "a cargo ship". However, one can not exclude the fact that some of the Greek words mentioned here penetrated into the Iranian languages during the Hellenistic period, which began after the conquests of Alexander the Great. This topic requires some careful research.

You can also find Greek loan-words in the Mordvinic and Mari languages. For example:

Mok vatraksh “a frog” – Gr. βατραχοσ “a frog”.

Erz vis’ks "shame" – Gr αισχοσ "shame".

Erz. nartemks "wormwood" – Gr ναρτεχ (some plant).

Mok klek "good" – Gr γλυκυσ "sweet".

Mok stir' "a girl" – Gr στειρα "sterile".

Mok. pindelf "to shine", an isolated word among all Finno-Ugric – Gr Πινδοσ (to PIE * kuei "to shine").

Mari kala "a mouse" – Gr γαλη "a marten", "a weasel", "a ferret".

Mari lake "a pit" – Gr λαχη "a pit" out of λαχαίνω "to dig".

The Baltic-Finnish languages have words which origin is an enigma for specialists. For example, in the etymological dictionary of the modern Finnish language, the possibility of ancient borrowing from Germanic languages is assumed for Fin. hepo (diminishing from hevonen), Est. hobu, hobune, Veps, Karel. hebo – all "horse", Mari čoma and Komi čan' – both "colt". However, ther it is noted that even the distant similarity for these words is not found among the Germanic vocabulary [HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007: 192]. Finnish linguist did not come to mind about accordance of the Baltic-Finnish words with Gr. ιπποσ "horse" phonetically adequate to Fin. hepo. Once again, Fin. and Veps. paimen "a herdsman" are identic to Gr. ποιμην "the same", but K. Häkkinen connects these words with Lith. piemuo "a herdsman" (ibid, 853), despite the fact that the Greek word corresponds to them much better phonetically.

The next enigma is the origin of the name of bat in the Baltic-Finnish languages: Fin. lepakko, Karel. yölepakko, Veps. öläpakkoine. Phonetic diversity speaks of borrowing, but from which language? Obviously from Old Greek where the word ἱέρᾱξ, -ᾱκος meant "hawk, falcon" and Frisk explained it as "high flying".

All these examples of Greek-Iranian and Greek-Western-Finnish matches give reason to assume that once some Greek tribes settled adjacent to the Iranian and the Finno-Ugric regions. The presence of the Greeks in the area of Gelonos is confirmed by a cluster of Greek place names along the banks of the Vorskla and nearby:

Abazivka, a village of Zachepylivka district of Kharkiv Region – Gr. ἄππας "priest". There is the village of Abazsvka in the Poltava Region, but its name supposedly comes from the surname Abaza.

Khalepie, a village in Obukhiv district of Kiev Region – гр. χαλεπός "heavy, hard, dangerous".

Khorol, a town in Poltava Region – Gr. χωρα, χωροσ "site, place, village".

Kovray, a village in Zolotonosha district of Cherkasy Region – Gr. κουρά "cutting hair, wool, branches".

Olbyn, a village in Kozelets district of Chernihiv Region – Gr. ὄλβος "prosperity, happiness", ὄλβιος "blessed, happy".

Poltava, a city and villages in Kharkiv, Lugansk and Rostov Regions – the name can have a different interpretation by means of Greek but the best Gr πόλις "a fortress, city" and ταΰς "great".

Saguny, a town in Podgorevsk district of Voronezh Region, the village of Sahunivka in Cherkasy Region – Gr. σαγήνη "great fish net".

Stasy, a village in Dykanka district of Poltava Region and the village of Stasy in Chernihiv district – Gr. στάσις "a site".

Tarandyntsi, a village in Lubny district of Poltava Region – Gr. τάρανδος "elk, deer".

Takhtaulove, a village in Poltava district – Gr. ταχύς "swift, rapid, prompt", Θαύλιος – epithet of Zeus.

Trakhtemyriv, a village in Kaniv district of Cherkasy Region – Gr. τραχύς, "raw, rocky, rough", θέμερος "solid, sturdy, hard".

As can be seen, there is in many cases good phonetic closeness of names to the Greek words. In addition, the compact location increases the likelihood of made interpretations. Religious features of the area designated by the place names such as Abazivka, Tahtaulove were continued by Slavic population, which can be validated by the existence here villige havin the root bozh (Slavik "god") – Bozhks Bozhkove, Bozhkovske.

It is also interesting that in the Seversky Donets basin, and in the nearest neighborhood there are about a dozen of names containing a component part Liman. This word is not Slavic, and it is believed that it was borrowed by the Turkish, Crimean Tatar from the Greek (Gr λιμήν "standing water, lake, harbor") already in historical time. This may be true for place names in Black Sea space which we do not take into account, but borrowing is unlikely for the Kursk, Belgorod, and Voronezh regions in Russia.

As can see, we have enough evidences of the presence of the Greeks in the Left-Bank Ukraine, but it is unclear how the way they got there. Two options are possible. Or they are going down from their Urheimat along the Dnieper River, settled in the valleys of its tributaries, or they were Callipidai, who came from the shores of the Hypanis. There is reason to consider the first option, since some place names that can not be deciphered by any language other than Greek were found along the Dnieper and Desna Rivers and further towards Poltava. They could mark the migration path of the Greeks. We are talking about such settlements as the Stase, Olbyn, Khalepie, Trakhtemyriv, Kovrae, Khorol, and others.

Thus, we have a reason to assume that the custom to make funeral structures of box type originated at the Greeks before their migration to the Peloponnese. Marshland at their ancestral home in the lower reaches of the Pripyat could be the reason of use of timbers and reed mats for graves construction. Once arisen custom became traditional also in new conditions, but could be modified depending on available materials. In the Peloponnese, it was developed into a construction of shaft tombs, while the timber burials began another modification of the primary structures.

Despite the fact that the Greeks were pioneers of Zrubna culture, its main carriers were Iranians. Besides, the Greeks in Ukraine were not so numerous to populate all of the space occupied by Zrubna culture. Otherwise, their ancestors would not have been assimilated in the future, as it actually happened. The Iranians, moving from Urheimat to the south, inhabited the area between the Dnieper and Don, having entered thus in direct contact with the Greeks, from whom borrowed the burial custom. In the future, migrating to Central Asia, they spread this practice even further.

The Iranians, like the Turks earlier, used wheeled vehicles to move. Thanks to the invention of the front turning device, the wagons became more maneuverable, which was a technical revolution for that time. Thanks to this improvement, it became possible, on the one hand, to overcome long distances by large groups of people on the off-road, and on the other, to create new effective chariot fighting tactics, thanks to which the Iranians gained a great advantage over many Asian nations. We defined the area of settlement of Iranians in the territory of the Zrubna culture, but there is reason to believe that part of the population of the Andronovo culture in Western Kazakhstan and Western Siberia were also Iranians, although originally the creators of the Andronovo culture was some Turkic tribe. A significant number of Iranian languages could not be formed only in the territory between the Dnieper and the Don (and even the Volga). Some of them were formed (or separately developed on the basis of European dialects) in Asia.

The considered migration directions of the Iranian tribes are contradicted by a significant number of monuments of Zrubna culture stretching along the banks of the Volga to Kama region. Traces of Iranians were not found there, so various assumptions can be made about the ethnicity of this part of the Zrubna-people. This could be the Turks who remained in Eastern Europe after the wide settlement of their relatives on the spaces of Europe and Asia. Mingling with the descendants of the creators of the Balanovo culture, they could give rise to the ethnic community of the Volga Tatars. On the other hand, the ancestors of the Hungarians were supposed to remain on the Zrubna territory living on their ancestral home between the Khoper and Medveditsa Rivers. Over time, some of them could move up the Volga, since the archaeological sites of the Magyars were discovered in the Lower Kama Region and the Bashkir Cis-Urals. With such opportunities, it is necessary to agree that the Zrubna culture was not ethnically homogeneous.

The sequel of the theme in

The migration of the Indo-European Peoples at the End of the 2nd and at the Beginning of the 1st Mill BC