Migration of Indo-European Tribes in the Light of the Language Correspondences

Following the next text we have to keep in mind that the present-day Albanian language is a descendant of Thracian (see The Areas of the Uprising of the Tocharian, Albanian, Thracian, Phrygian Languages

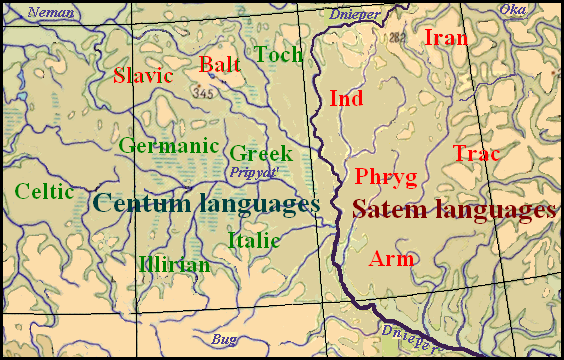

As it is known, according to the principle of reflection of palatalized velars or in the form of affricates and fricatives, either in the form of pure velars, all Indo-European languages are divided into two groups Satem and Centum. The Satem group includes the Indo-Aryan (Indic), Iranian, Baltic, Slavic, Albanian, Armenian, Phrygian, Thracian languages. The Hittite-Luwian (Anatolian), Greek (Hellenic), Italic, Germanic, Celtic, Tocharian, Illyrian languages belong to the Centum group (POKORNY JULIUS. 1954: 376). However, there is little disagreement about this division, for example, the Phrygian language is referred to the group of "centum" by G. Province, although it is questionable (KRAHE HANS, 1966: 30). Currently, the same view adheres to F. Kortlandt (KORTLANDT FREDERIK. 2016).

In principle, this separation could affect the location of individual Indo-European languages so that the two groups would have fairly clear geographical boundary, but hardly such can be found. Indeed, one would assume that the division occurred on the principle "east-west" as it was supposed by W. Porzig (PORZIG W. 1964: 315). In such a case, the boundary could lay along the Dnieper River, as most Satem language areas were located on the left bank but all the Centum ones did on the right bank. However, the location of the area of the Centum Tocharian language between the Satem Indo-Aryan and Baltic languages contradicts this assumption. The complexity of the division of the Indo-European languages to the groups Satem and Centum due to the involvement of other new data resulted that some scientists even refuse this division (GORNUNG B.V. 1963: 14; VINOGRADOV V.A. 1982: 259). But the contradictions can be resolved for the most part by adopting and developing the explanation of this division proposed by Agnia Desnitsky:

Proto-Albanian belonged to the Satem group languages, preserved the row of palatal guttural consonants, and carried out their assibilation. However, satemization was "inconsistent" in this language like as in the Baltic languages (less for Slavic ones). This "inconsistency" can be considered as a feature of a fairly wide transition band in the central part of the Indo-European space, which could consist apart from the Baltic and Proto-Balkanic also of the Illyrian (with Messapian) and Thracian languages. The tendency to assibilation of palatal consonants was powerful innovation of the period prior to rupture of the territorial contacts between different parts of the Indo-European community. This innovation, moving from east, weakened to the central zone, meeting with the approaching from the west the tendency of the neutralization of the opposition of palatals and velars sounds (DESNITSKAYA A.V. 1966: 11-12).

Illyrian could not be in the central part of the Indo-European space, and the wave of the assibilation of the palatal could not reach it, it remained the expressed Kentum language. This wave, according to A. Desnitsky, arose under the influence of Finno-Ugric languages, which include a rich set of sibilants s, s’, š,, and only two the gutturals k and q’, while the Indo-European languages had one fricative s and a large collection of guttural voiced, voiceless and aspirated consonants (DESNITSKAYA A.V.1968: 12). Since the Albanian language manifested “inconsistent Satemization”, A. Desnitsky places it in the middle of the Indo-European space, where the influence of Finno-Ugric languages was felt less. The central position of the Albanian language among Indo-European languages was further confirmed by two other facts which were given by A. Desnitsky:

The whole dialect space, which Proto-Albanian belonged, according to the feature of the transition of the Proto-Indo-European scheme of three short vowels *e, *o, *a to the schema of two vowels *e, *a (in Slavic *o) was opposed to the vast area in southwest and south of the Indo-European space (Celtic, Italic, Greek, Phrygian, and Armenian), where the three-part scheme was preserved, and Indo-Iranian region where three-term model was reduced to a one-term one *o (DESNITSKAYA A.V.1966: 10).

That is, three areas existed: the area A, which has kept all three of the ancient Indo-European short vowels, the area B included the Proto-Albanian, that is Thracian, language, and characterized by displaying them in two vowels, and the area C where they were reflected by one vowel.

The second fact is very important also for determination of the order of migration of speaker of particular Indo-European languages from their Urheimat:

Indo-European voiced aspirated stops *bh, *dh, *gh transformed in Proto-Albanian to simple voiced stops b, d, g, and coincided with the voiced stops which were preserved from the Indo-European state. In this respect, the Proto-Albanian language has evolved the same way as a lot of languages, including Baltic, Slavic, Germanic, Illyrian and Thracian, Celtic, and Iran. According to this feature, these languages were objected to Italic, Venetian and Greek lost of the voiced aspirated row, but have retained the distinction of three rows. An important innovation of the vast area, stretching from the Iran language area on the east to the Celtic area on the west, was a uniting of two rows of the Indo-European stops (simple voiced and aspirated voiced) into one row. Only the German dialect area in the center of this area did not carry out this innovation, having carried out Sound Shift (Grimm's law") and keeping the original distance of the relationship between the three rows of the Indo-European stops (Ibid: 11-12.)

Thus, the important is the merger of voiced aspirated and voiced plain stops in one row of voiced plain stops in the Celtic, Germanic, Slavic, Baltic, Iranian, Armenian, Thracian, Albanian, and Illyrian languages i.e. voiced aspirated stops did not survive in these languages. Voiced aspirated stops were preserved in Greek, Italic, Indo-Aryan (one can not say sure about Tocharian), another thing is that they reflected in each language in different ways later. It implies that the ancestors of Italics, Greeks, and Indo-Aryans would have been among the first to leave their Urheimat and so saved the old Indo-European sound composition. Having lost contact with each other and got into the neighbourhood with native speakers of another sound structure, they could fall under the different language influences and therefore, e.g., Greek voiced aspirated bh, dh, gh were transformed in φ, θ, χ, and Latin bh, gh did in the f, h accordingly. Unvoiced aspirated ph and th reflected in Greek to φ and θ but coincided with p і t In Latin. The languages of other Indo-European peoples, who remained in their previous places, were developed by more or less common phonetic laws, and so all they have lost aspirated bh, dh, gh, ph, th, kh (including the Germanic languages, although there we see Sound Shift).

Reflection of stops in individual Indo-European languages

| Voiced | Voiceless | Ind | Gr | Lat | Germ | Balt | Slav | Celt | Iran |

| b | b | β | b | p | b | b | b | b | |

| bh | bh | φ | f | b | b | b | b | b | |

| p | p | π | p | f | p | p | (0) | p | |

| ph | ph | φ | p | f | p | p | p | p | |

| d | d | δ | d | t | d | d | d | d | |

| dh | dh | θ | d | đ | d | d | d | d | |

| t | t | τ | t | þ | t | t | t | t | |

| th | th | θ | t | þ | t | t | t, th | t | |

| g | g | γ | g | k | g | g | g | z | |

| gh | gh | χ | h | g | k | g | g | z |

The location of the primary areas of Italics and Greeks and their later habitat places, as well as the time of their arrival there, confirm the assumption that they were among the first to leave their ancestral home after those Indo-Europeans unknown to us, who could inhabit the southernmost area of the Indo-European territory between the rivers the Dnieper, Teterev, and Ros'. It cannot be ruled out that this first migration wave of Indo-Europeans reached Asia Minor at the end of the 3rd millennium BC, coming there from the Balkan Peninsula:

The archaeological cultures of the last quarter of the 3rd mill. BC in Asia Minor came to really dramatic changes. These changes suggest the emergence of new ethnic elements that can be identified with the ancient Anatolians – but rather about their appearance from the west than from the east. (DIAKONOV I.M. 1968: 26-27).

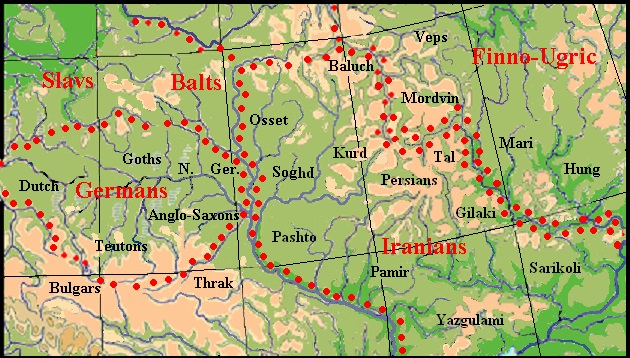

More confident we can talk about the migration of the Greeks, who in their motion to the Balkans could use the waterways. In contrast, Italians traveled through the land. The movement of the Indo-Aryans had to be prevented by the Phrygians and Armenians, therefore, the latter migrated so which did not prevent the movement of the Indo-Aryans and at the same time remained near the Indo-European territory. The Tocharians should still stay in their Urheimat for some time when it Italics, Greeks, and Indo-Aryans already went away (PORZIG V., 1964, 319). The Thracians (Proto-Albanians) were involved in this movement of Indo-European populations and settled somewhere in the center of the Indo-European territory, which can explain the localization of their ancestral home by Agnia Desnitsky:

The outpouring of the relation of Albanian with the North-Indo-European languages (Baltic, Slavic, Germanic) gives a reason for searching For-Balkan homeland of the group of Indo-European tribes to which belonged also the ancestors of the Albanians, somewhere in the neighborhood of the settlement space of the North-Indo-European tribes (DESNITSKAYA A.V. 1984: 220).

It can be assumed that the Phrygians and proto-Armenians had crossed the Dnieper before the Thracians, and later moved somewhere not far to the south, since they still remained in the zone of common Indo-European linguistic influences. Obviously, these influences were less than on Thracian, since Armenian remained a distinctly expressed "Satem" language. At the same time, under such an assumption, the centumism of the Phrygian should be considered problematic. The Thracians inhabited the triangle between the Teteriv, Ros, and Dnieper rivers (see the map below). This stopped the process of "satemization" of the Thracian language, since the Dnieper, as a powerful border, was preventing the contacts of its speakers with the Iranian tribes who spoke the languages of the "Satem" group. Thus, Western influences prevailed in the Thracian language. And vice versa, after the departure of the Tochars, the ancestors of the Balts, moving eastward, came into direct contact with the speakers of the Iranian languages, and later with the Finno-Ugric peoples, and therefore in their languages there was a transition of palatalized velar k', g' into the dental or alveolar sibilants. That is, the Baltic languages, primarily belonging to the Centum group, fell under the satemization process later than the rest of the Satem languages. At the same time, it is natural that satemization, or rather, the assimilation of the palatalized progressed in more oriental languages. For example, the Western Baltic languages mostly retained the sound k where in the East Baltic it was reflected in c, cf: Lith.kelis – Let. celis "knee", Lith. kepure – Let. cepure "cap, hat", Lith. kietas – Let. ciets "hard", Lith. kilpa – Let. cilpa "loop, hinge", Lith. kiltis – Let. cilts "tribe" etc. In Slavic languages, a similar phenomenon can be observed in the reflection kv – cv. According to V.I. Abaev, V. Georgiev believed that the assibilation of palatals in the Indo-Iranian language occurred no later than the 3rd millennium BC, while in Slavic "in an era not very distant from the most ancient written monuments" (A. ABAYEV V.I. 1965: 141) Obviously, the satemization of the Slavic languages took place even later than in the Baltic under the influence of the local substrate when the territory of the Balts was inhabited by the Slavs.

|

Habitats of the Iranian and Germanic tribes in II mill. BC..

According to the lexical and statistical data on which the model of the kinship of Indo-European languages was built, the Albanian language has the greatest number of common words (excluding the common Indo-European lexical fund) with Greek. In their ancestral homeland, the Proto-Albanians did not have direct contact with the Greeks, therefore, the total number of Albanian-Greek correspondences included Greek borrowings into Albanian from Greek already during the time of the Thracians in the Balkans. If we exclude these borrowings, it turns out that Albanian has the most lexical correspondences with the Germanic languages. The Thracians also did not have contacts with the Germanic tribes during the formation of their language, but, having crossed the Dnieper, they found themselves in close proximity to their habitats (see the article Germanic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age). This neighborhood determined the German-Albanian connections, which are found in the phonetics, vocabulary and grammar of the Albanian language.

Below are some characteristic cases of Albanian-Germanic lexical correspondences given by A. Desnitsky (DESNITSKAYA A.V. 1965: 33-38). Only a part of them is taken into account in the etymological work of Yu. Pokorny. Other languages of the North Indo-European area are also involved in some of these correspondences:

1. Alb. barrё (IE *bhorna) «burden» — Goth., O.H.G, O.Icl. barn "child".

2. Alb. Gheg bri (stem brin-) «horn» (IE. *bhr-no-) — Sw. dial. brind(e) (*bhrento), Norw. bringe "elk". Also cf. Let. briedis, Lith. briedis "elk".

3. Alb. bun "shepherd's hut in the mountains", originally "housing", buj/bunj “sleep” out of IE *bheu, *bhu-. Close by meaning: Goth. bauan, O.Icl. būа, O.H.G., O.Saxbūаn "live, dwell, cultivate (land)"; O.Icl. būа, OE bū "housing".

4. Alb.dhi, "goat" (Proto-Alb. *diga) — O.H.G ziga, IE *digh "goat".

5. Alb. gjalm, gjalmё "lace, string" — O.H.G sell, Sax. sel, O.Eng. sal "rope", Goth insailjan "to rope".

6. Alb. kale "fish bone, awn of the ear" (IE. *skel- "cut") — Goth. skalja "shingles", O.Icl. skel "flake", O.H.G scāla "a shell of the grass". Formations from this root are also represented in other Indo-European languages. But only in the Albanian and Germanic have a special similarity in the structure of the stem and in the meaning.

7. Alb. helm "poison, sadness, grief" — O.H.G. scalmo "plague", skelmo "criminal". Out of IE. *skel "cut".

8. Alb. hedh «throw out» — Sax. skiotan, O.H.G. skiogan, OE. sceotan "throw, shoot".

9. Alb. Gheg. lâ, Alb. Tosk le (*lədnō) "leave", participle lane (*lədno-) "left" — Goth., OE. lētan, O.Sax. lātan, O.Icl. lāta "leave"; adjective Goth lats, O.Icl. latr "sluggish, lazy".

10. Alb. (i)lehtё "light" (IE. *legik-, *length-) — Goth. leihts, O.H.G, līhti), OE. leaht "light". Adjectives with a similar meaning, derived from the same root, are represented in a number of Indo-European languages, but only in Germanic and Albanese the stem of the adjective has the suffix -t-.

11. Alb. lesh "wool, fleece" — Dt. vlies, M.H.G. vlius, O.Eng fleos "sheep skin, fleece". IE *pleus- "pluck wool, feathers".

12. Alb miell, "meal" — O.H.G. melo, melaues, OE. melu"meal". This is a case of complete identity in the structure of the stem and meaning.

13. Alb. mund 1) "be able, to be able to" 2) "to win, to overcome" mund "effort, hard work." These words, which in Albanska give a variety of derived formations, are usually associated with O.H.G. muntar "cheerful, alive", munt(a)rī "zeal, diligence", Goth mundrei "goal" and are assotiated with IE. *mendh "to direct thoughts, to be alive." The above Albanian words that convey the meaning of “physical strength, physical effort, victory in a fight” clearly stand out among the tribes of Indo-European formations associated with the root *men-. The development of both Germanic and Albanian meanings is well explained from the primary meaning “hand” (Gmc. mundō "arm, protection", Albanian verb mund "to be able to win" is an ancient derivative).

14. Alb. Gheg rū, rūni, Tosk. rёndёs «abomasum» — M.H.G renne "abomasum".

15. Alb rē «cloud» – O.H.G. rouh, Sax rōк, O.Icl. reykr "smoke", Gmc. *гauki.

16. Alb. shparr (*sparno-) — a kind of oak (Quercus conferta) — O.H.G., O.Sax, sparro, M.H.G. sparre "log, beam, rafter", O.Icl. spari, sparri "log, beam" (common Gmc. *spar(r)an), O.H.G. sper, OE. spere, O.Icl. sparr "a spear".

17. Alb. shpreh «speak, express» (*spreg-sk-) – O.H.G. sprehhan, Sax., OE. sprēcan "speak».

18. Alb lapё, lapēr "hanging, flabby piece of skin; belt, inedible piece of meat; skin hanging on the neck of an ox; flap" — O.H.G. lappo, lappa "hanging piece of leather, fabric", O.Sax., lapp "skirt, a flap of klothing", Ger. Lappen "flap".

19. Alb flakё "flame", flakёroj "flicker, blaze", flakoj "flash" – M.H.G. vlackern, Ger. flackern "to tremble (about a flame), to flicker, to blaze", O.Eng. flacor "flying", cf. Eng. flakeren "flit". Here we have a vivid case of analogy in expressive word creation, which has given such a similar formation in all respects that it can hardly be considered an accidental analogy. Probably, these similar formations arose in an atmosphere of territorial contacts of the ancient Germanic and Thracian tribes. This also applies to the following group of words:

20. Alb. flater, fletё, -a "wing"», flatroj "flit", flutur "butterfly", fluturoj, fluroj "fly, flit". Cf. Ger. flattern "flit", Eng. flutter, flitter "flit, flutter their wings". There are options with voiced intervocalblastic: Erly Ger. vladern, cf. Fledermaus (Eng. flittermouse) "microbat". Expressive onomatopoeia, violating the laws of sound correspondences, led to the creation of strikingly similar lexical units in the now territorially distant from each other but had been contacting at some time (in the prehistoric era), the Germanic and Albanian languages. The corresponding formations are widespread in both the Germanic and Albanian dialects, which indicates their antiquity.

In the field of grammar, the connection of the Albanese language with the Germanic are manifested in the preservation of some specific features of the Indo-European inflections, in the types of morphological structures, in the development of the phonological structure:

In the development of alternations of vowels and their morphological functioning, the Germanic and Albanian languages are very similar. The similarity is not limited to the remnants of the Indo-European quantitative ablaut in some verb paradigms… This similarity is especially striking in the chronologically later sound alterations of assimilative nature, which are very common in the Albanese language and represent, in their morphological use, a complete analogy to similar phenomena of Germanic languages. It can be noted that it looks brighter and more convincing than the similarity of the processes of assimilative variation in the Germanic and Celtic languages, noted by the authors of the Comparative Grammar of the Germanic Languages as one of the isogloss of the Celto-Germanic area. Comparison of morphological structures of modern Albanian and Germanic, for example German, languages show close analogies in the dissemination and functioning of the phenomena of internal inflection as a means of expressing grammatical meanings. In the nominal inflection of alternating vowels (more precisely, umlaut) in both language types are used in the formation of the foundations of the plural nouns, for example Alb. dash "ram" — pl. deske, natё "night" — pl. netё, cf. Ger. Gast "guest" — pl. Gäste, Nacht "night" — pl. Nächte (DESNITSKAYA A.V. 1965: 40)

The study of Baltic place names outside ethnic territories gave grounds for hypothesizing the migration of a part of the Balts to the Balkans supposedly in I millennium BC. Examples of toponymic correspondences on the territory of Romania, where the Proto-Albanians could be, are given below.

Balta Albă, a commune and village in the county (județ) Buzău – the most convincing Baltic toponym in Romania, since the double name consists of the Baltic and Romanian words having the same meaning "white" (Lith. baltas, Let. balts, Rom. alb). What was the original name, remains to be seen.

Suveica, a village in Mureş County – the village of Suviekas in Zarasai District, Lithuania. Cf. Lith. suvaikyti "drive together, round up".

Țuțora, a village in the județ Jassy – good compliance with the name can be seen in the Baltic place-names: Lake Čičirys in the northeast of Lithuania, near the village of Suviekas in the Zarasai district, the Ciecere River, rt of the Venta River in Latvia. In Ukraine, there is a village Tsitori (Ternopil Region in Ukraine).

Vârleni, a village in the județ Vâlcea – Lith. varlė "frog".

The presence of the Balts in the Balkans explains the special Thracian-Baltic and Dacian-Baltic linguistic connections, which were investigated by the Bulgarian scientist I. Duridanov Ivan. He found 60 separate lexical correspondences between the Dacian and the Baltic languages and 16 more possible, and between Thracian and Baltic – 52 and 19 respectively. At the same time, there were only 14 common Thracian-Dacian-Baltic matches.(DURIDANOW IWAN. 1969: 100). These numbers may seem small, but it should be borne in mind that the vocabulary of the Thracian and Dacian languages has been preserved in very small quantity, so it is not the absolute numbers that are important, but their comparison with the data on the connections of Thracian and Dacian with the languages close to the Baltic. First of all, we mean the Slavic languages, but no special Dacian-Slavic or Thracian-Slavic ties were found ibid which is quite understandable in the absence of any prerequisites for this. The data of Duridanov are confirmed by Proto-Albanian and Pro-Baltic connections. Especially impressive, according to Desnitskaya, are lexical correspondences that stand out for their specificity.

Alb. ligё «illness» (< Proto-Alb. *ligā), i lige «ill; bad» (< Proto-Alb. *ligas), i ligfhte «weak, powerless» (< Proto-Alb. *ligustas) – cf. Lithligà, Let. liga «illness», Lithligustas «ill»;

Alb. mal «mountain» (< Proto-Alb. *malas) – Let. mala «bank, shore»;

Alb. mot «year; weather» (< Proto-Alb. *metas) – Lith*metas «time», pl.: metai «year»;

Alb. i thjermё «grey» (< Proto-Alb. *sirmnas) – Lithsirmas, siřvas «greyй» (DESNITSKAYA A.V. 1990: 10).

The prolonged migrations of the Thracians from their ancestral home to the Adriatic coast and their long stay in the zone of contact with speakers of languages of different groups resulted in rare typological features of Albanian grammar. According to A.Yu. Rusakov, the Albanian language has eight to nine of the twelve characteristics of the SAE (Standard Average European) area and, in addition, is also characterized by certain typological similarities with the Iranian, Baltic, and Turkic languages (Rusakov A.Yu. 2004: 259-274). All this made it difficult to establish genetic links between the Albanian language and other Indo-European languages.

Now we can find an explanation for the fact why the Albanian language has so many common words with the Germanic and Baltic languages (see data on the number of common words in the Albanian and other Indo-European languages above) in the assumption that ancient speakers of Proto-Albanian language settled in close proximity to the settlements of the Germanic and Baltic tribes.

Such complex migration route of the Proto-Albanians and their long stay in the zone of contact with speakers of different language groups explains the rare typological features of the Albanian grammar. According to A. Rusakov, Albanian language has eight or nine of the twelve features of the space SAE (Standard Average European) and, in addition, is also characterized by certain typological correspondences with the Iranian, Baltic, and Turkic languages. (RUSAKOV A., 2004, 259-274). It will be shown further where and when the Proto-Albanians (Thracians) had contacts to explain to a certain extent, these correspondences.

Now, knowing the origin of the Albanian language from Thracian, we can find an explanation for the fact that Albanian has so many common words in German and Baltic languages (see Data on the number of common words in Albanian with other Indo-European languages above) – Thracians have long been in close proximity to the settlements of the Proto-Germanic and Proto-Baltic people. Their difficult migration path and a long stay in the area of contact with native speakers of other groups explain the rare typological features of Albanian grammar.

More detailed about migration of Indo-European peoples in the section

The First Great Migration