Kurds at the Origins of Lithuanian Statehood

When I published the first version of the article on this topic, I assumed that the information about the unexpected circumstances of the formation of the Lithuanian statehood would be of great interest to historians. However, this did not happen. What happened is what happens in most cases – novelty meets with skepticism and, if it finds a response, only not to see other facts to confirm it. And such facts are available to historians. T. Baranauskas in his work claims that Netimer mentioned in Saxon sources for 1009 was not the ruler of Lithuania. It is "more likely to connect him with the neighboring lands of the Yotvingians" (BARANAUSKAS TOMAS. 2000: Summary, 245-272). This was the first mention of Lithuania and the ethnicity of the first known prince is an important fact for the formation of the state. After the news about the Kurds as being involved in this process, those interested in the origin of Netimer only had to look into a Kurdish dictionary to find out that this name in Kurdish means "Immortal" (Kurd. netemirî). For a prince, the name is quite appropriate, but skeptics may treat this fact as a coincidence, so we return to this topic again.

Never thinking of studying the history of Lithuania, working on the history of the Cimmerians some part of whom were Kurds (see Cimmerians in Eastern European History), I accidentally discovered that the names of some princes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania sounded like words in the Kurdish language. This interesting fact provoked an attempt to use materials from the Kurdish vocabulary to interpret other names of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania as well. This turned out to be possible for the following:

Dangerutis, Daugerutis, a prince of Lithuania before 1213 – Kurd. daw, dûv 1. "tail", 2. "hem" gerd "large";

Mindaugas, Mendog, the first known Grand Duke of Lithuania and the only Christian King of Lithuania (1253–1263) – Kurd. mend "modest", awqas "so much" ("very"?);

Treniota, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1263—1264) – Kurd. ture “angry”, nêt “thought, desire”;

Vaišelga, Wojsiełk, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1264—1267) – Kurd. xwey "master", şûlq "wave";

Švarnas, Szwarno, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1267/1268—1269) – Kurd. şarm "shame", "shyness" out of *şfarm as the metathesis of OIr. *fšarma "shame";

Traidenis, Trojden, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1269—1281) – Kurd. tureyî “anger”, dên “sight”;

Daumantas, Dovmunt, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1282—1285) – Kurd. devam “long”, entam “limb”, “stature”;

Pukuwer, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1291—1295) – Kurd. pevketin “make peace, agree”, wêran “destroyed”;

Vytenis, Witenes, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1295—1316) – Kurd. wetîn "love", "wish";

Gediminas, Gedymin, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1316-1341) – Kurd. hedimîn 1. "to collapse, fall apart", 2. "perish";

Algirdas, Olgierd, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1345-1377) – Kurd. ol "creed, religion", gerd 1. "great", 2. "great man";

Jogaila, Jagiełło, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1377-1392) and the King of Poland (1386–1434) – Kurd. egal "hero", yê egal "heroic", lawe (lo) "child, son";

Kęstutis, Kiejstut, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1381-1382) – Kurd. key "king", and the second part of the name may come from the Indo-European root word meaning "to stand" that has disappeared from the Kurdish language (cf. Kurd. stûn "pillar");

Vytauta, Witold, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1392-1430) – Kurd. xwî "prominent, obvious", tawet "strength, power";

Švitrigaila, Świdrygiełło, the Grand Duke of Lithuania (1430-1432) – Kurd. swînd "oath", -r – the case suffix, egal "hero", lawe (lo) "child, son".

That the rulers of Lithuania were of a different ethnicity is confirmed by the information of the Anglo-Saxon merchant Wulfstan, who visited the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea at the very end of the ninth century on the orders of King Alfred. He described some customs of the Prussians: their kings and nobles drank kumiss, while the poor and slaves enjoyed mead (BARONAS DARIUS, ROWELL S.C. 2015: 27-28). From this message, we can conclude not only about the different ethnic origins of the nobility and common people, but also that the nobility must have come from the steppes, where kumiss was a common drink.

The name of the country Lithuania does not have a satisfactory etymology, although some scholars believe that the name should come from the ethnonym "lietuvis" ("Lithuanian"). Now Latvians call Lithuanians "leišiai", so the original form of the ethnonym could have been "liečiai" or "leičiai", which is unconvincing. Another version has more plausible arguments:

Thus far, the most widespread version is that the name of Lithuania is derived from the name of the Lietauka, a small river that flows into the Neris near Kernavė. It is traditionally thought that the core of the Lithuanian state was the Land of Lithuania – in the strict sense – that was between the Nemunas and Neris Rivers in early historical times. Thus the Lietauka River, a right tributary of the Neris, flowed towards the Land of Lithuania, and not necessarily in Lithuania itself. In this case, the name of the river should have been derived from that of the land, and not the other way around [EDINTAS ALFONSAS, .. 2013: 13].

Due to this uncertainty, the country could have been named by the Kurds – cf. Kurd. lûtf, litf "mercy, kindness". It is believed that this Kurdish word was borrowed from Arabic [TSABOLOV R.L., 2001: 596]. In fact, the Cimmerians-Kurds must have borrowed it from the Akkadian language during their stay in Asia Minor. The possibility of such an explanation is confirmed by other borrowings from Kurdish into the Baltic languages

Lith. balvas, Let. balva "gift, bribe" – Kurd. belwa "temptation";

Lith. daba "nature, kind, way", Let. dāba "natural quality, habit, nature", Blr. doba "nature" – Kurd. dab "custom, disposition, habit", which, in turn, was borrowed from Akkadian (Ar. tabia “nature”).

Lith. ežeras, Let. ezers "lake, pond" – Kurd. zirē "lake";

Lith. galata "deceiver" – Kurd. galte "joke";

Lith. kūdikis "child" – Kurd. kudik "youngling, baby";

Lith. manga "lewd person, prostitute" – Kurd. mange "cow, she buffalo";

Lith. miškas "forest" – Kurd. mêşe, bêşe "forest, grove";

Lith. Nemunas "Neman" – Kurd. nem "wet, moist", yan "side";

Lith. vaisba "trading" – Kurd. bayi "trading".

The presence of Kurds in Lithuania is confirmed by numerous place names of the country, deciphered using the Kurdish language, the locations of which are plotted on a map (see Google My Maps below). Here are some examples of interpretations:

Klaipeda (old name Kalojpeda) – Kurd. kala "goods, property", peyda, pêde "be found".

Telšiai – Kurd telaš 1. "yarn", 2. "sliver, shavings", 3. "effort".

Šiauliai – Kurd. şewl "a ray of light", "shine".

Kadikai – Kurd. kedî "accustomed", kaye "game". Cf. Kadıköy in Turkey.

Tarakonys – Kurd. tarî “dark”, konî "spring, well". Cf. Tmutarakan.

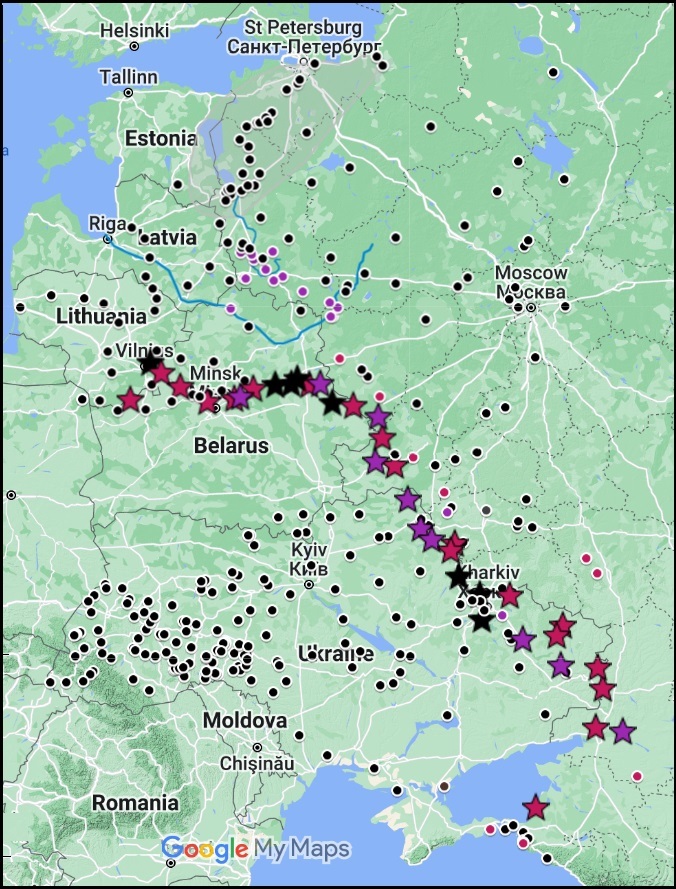

To explain the presence of Kurdish onomastics in the history of Lithuania, it was suggested that Prince Mstislav the Brave resettled the Kurds (like the Polovtsians of the chronicles) from the Tmutarakan Principality to the Seversk land after he became Prince of Chernihiv. The Kurds were part of the population of this principality, located in the lower reaches of the Kuban. The chronicles mention the leader of the local Circassians, Rededya, who was killed by Mstislav in 1022. He could have been a Kurd, if we take into account the Kurd red "to disappear, to vanish", eda "payment, settlement". In the multinational composition of the population of the Tmutarakan Principality, in addition to the Kurds and Circassians, there must have been some unknown Baltic tribe. (см. Ancient Balts Outside the Ancestral Home). The Balts of the Kuban region must have had some relations with the Kurds and Circassians since the time of the Bosporan Kingdom, which existed before the Tmutarakan Principality in the same area. They did not lose touch with their ancestral homeland, and the route they laid here from the Baltic could have been used by other peoples during migrations. Previous research has shown that peoples leave their traces in toponymy along migration routes since some migrants remain for permanent residence in places convenient for settlement. In search of a probable route for the movement of the Balts, along with place names of Baltic origin, four kilometers from the village of Murygino in the Pochinkovsky district of Smolensk Region in Russia, the previously existing village of Kimborovo, the birthplace of N.M. Przhevalsky, was discovered. The village's name corresponds to the self-designation of the Kurds of that time, and in the Tver Region, there is a city of Kimry. The ethnonym Cimmerians (gr. Κιμμέριοι, Akkad. gimirrai) could have come from Kurd. gimîn, gimi-gim "thunder" and mêr "man". The name Cimbri is derived from it. A thorough study of the surrounding area showed that in the border regions between Ukraine and Russia, there is a large concentration of Kurdish place names, among which there are also those decipherable using the Kabardian language, closely related to Circassian. Some of them are located next to the Baltic ones. This made it possible to reconstruct the supposed route from the Baltic to the Kuban region, shown on the map below.

The movement route of peoples between the Baltics and the North Caucasus

On the map, Kurdish place names are marked in black, Kabardian in purple, and Baltic in red. The route is marked with asterisks.

The map clearly shows the movement route of peoples from the Baltics to the Taman Peninsula and back, marked with Kurdish, Baltic, and Kabardian place names. Among others, there are the following:

Phanagoreia – Kurd. fena "missing, abandoned", gor "grave",

Achuyevo – Lith. ačiū "thanks"",

Yudino – Lith. judinti "move, stir",

Lypchanivka – Kabard. Lъepshch "god of blacksmithing",

Balakliya – Kurd. belek “white”, leyî – “flow, stream”,

Chuhuiv – Kabard. shchygu "plateau, surface",

Vilcha – Lith. vilkis, Lith. vilks "volf",

Zolochiv – Kurd. zarū "leech", Pers. zalū "worm", cew "river",

Mezenivka – Kabard. mez "forest", en "whole, all",

Loknia – Lith. Lukné, Let Lukna – rivers,

Karyzh – Kabard. kIerezhyn "leak",

Shalygine – Kabard. shylegu "turtle",

Esman' – Kurd. e’sman “sky”,

Litizh – Lith. Leitiškiai – a village in Lithuania,

Zhykhove – Kabard. zhykhu "fan" (out of zhy "wind"),

Shaulino – Kurd. şewl "a ray of light", "shine"",

Vorga – Kabard. werq "nobleman",

Bashary – Kyrd. baš "good", ar "fire",

Liamna – Lith. liemuo "stature, trunk", Liminas – about ten lakes and a village in Lithuania, this word refers to the Indo-European root (s)lei "slippery, smooth" (Gr. λειμών "floodplain, wet meadow", λιμήν "bay", Ger. Lehm "clay" ao.) [Fraenkel E. 1962. Band I, 365].

Khawkholitsa – Kurd. xav "unripe, raw", xol "earth",

Budagovo, village in Smolyevitsky district of Minsk Region – Kabard. bydag “hardness, strength“.

Gerdushki – Kurd. gerd "great", ûşk "dry, hard",

Tarakonis – Kurd. tarî "dark", kanî "spring, source".

The emergence of the Lithuanian state is a great mystery for historians and since the time of Karamzin ways to solve it have been sought. Having thoroughly studied the chronicles of Martin Gall, Vikenty Kadlubek and the works of Jan Dugosz, the Ukrainian historian of the 19th century defined the starting conditions for the emergence of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as follows:

Based on the data presented, we believe that until the middle of the 13th century, the Lithuanian tribe did not constitute a state; it was a scattered mass of small volosts, governed by independent leaders, without any political connection with each other (ANTONOVICH V.V. 1885: 16)

Since these lines were written, nothing fundamentally new seems to have been discovered in historical documents about the emergence of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Historians have repeated the same worn-out cliches about this process for over a hundred years. A great authority on the history of Eastern Europe describes it in a few general words:

Lithuanian grand dukes were the great warlords of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Europe. They conquered a vast dominion, ranging from native Baltic lands southward through the East Slavic heartland to the Black Sea. Picking up the pieces left by the Mongol invasion of Kyivan Rus’, the pagan Lithuanians incorporated most of the territories of this early East Slavic realm. (SNYDER TIMOTHY. 2003: 17).

In his book, Snyder claims that he is speaking out against national myths and notes that refuting them is like dancing with a skeleton, from whose embrace it is difficult to escape ((i>Ibid: 26). Historians try to fight national myths, but they themselves sometimes repeat their own myths, without even noticing that they are dancing with a skeleton. According to Snyder, the myth-makers assertions are based on the self-evident (Ibid: 27). In this case, it seems self-evident that the Grand Dukes of Lithuania had to be Lithuanians, but it did not occur to him to look for evidence for this assertion, and he does not suspect that he himself is among the myth-makers. Speaking a lot about nations and nationalities, he overlooks the fact that historically there can be a very big difference between them, and xenocracy often determines the process of state formation.

One might think that Lithuanian historians would find relevant evidence of pagan times preceding statehood in Lithuanian folklore and language, but even the reign of Mindaugas, in their opinion, was only a historical episode (EDINTAS ALFONSAS>,.. 2013: 13). Meanwhile, there was a process of transforming paganism into an institutional system, which implied its support through donations (ibid., 25). Only people of a certain social status could make significant donations, but Lithuanian historians do not report anything about their existence. They also do not write about the migrations of Lithuanians outside the ethnic territory and its causes.

The analysis of onomastic material allows us to reconstruct the prehistory of the Lithuanians from an unexpected point of view. As it turned out, the names of some cities of the Bosporan Kingdom can be deciphered using the Baltic languages Anapa – Lith. anapus «on the other side»; Panticapaeum – Lith. pentis "heel (foot)", kāpas «hill, grave», Patreus – Lith. patraukyti "to seize", etc. The presence of the Balts in the Northern Black Sea and Azov regions is confirmed by anthroponymy. Proper names of people, deciphered with the help of Baltic languages, can be found in the obscure places of the works of ancient historians and epigraphs left by participants or witnesses of real events: Βαλωδισ (balo:dis), Βραδακος (bradakos), Λοιαγασ (loiagas), Παταικοσ (Pataikoc). The political structure of the kingdom was a complex system. The local tribes were ruled by a single monarch, who was also an archon in the republican tradition of the Greeks. The ruling elite of the state were Kurds. Several of its rulers bore the name Mithridates, which can be easily deciphered using the Kurdish language: Kurd midîrî "leadership", dad "law", "justice". Most of the other rulers of the kingdom also bore Kurdish names. Among them are the following:

Pairsad (Παιρισαδης), the names of several archons of the Bosporan kingdom, as well as a dozen other persons in the territory from Tanais to Thrace – Kurd. peyar “infantryman”, sed “a hundred”.

Reskupor (Ρησκουπορις), the names of several kings of the Bosporan kingdom – Kurd. rȇşî "beard", por "hair".

Rumetalk (Ροιμηταλκου (roume:talkou), a Bosporan king – Kurd. rûmet “cheek” and elqe “circle”.

Savromat (Σαυροματης), the names of several kings of the Bosporan kingdomи – Kurd. sawîr "fear", mat "startling, stunning".

Spartok (Σπαρτοκος), the names of several kings of the Bosporan kingdom – Kurd. spar "order", toqe "royal decree", spartin "entrust".

Contradictory opinions of historians about the prerequisites for the creation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania give reason to believe that in this case there was an "import of political technologies". The Kurds, who already had political experience, being part of the Bosporan Kingdom, can be considered "importers". They could apply this experience among the barbarian population of the Eastern Baltic, just as it always happened in medieval Europe:

It is known that not a single state emerged in early medieval Europe as a result of self-development alone – all of them emerged, if not as a result of the capture of Roman territory (the synthesis path), then under the influence of already existing states of the Mediterranean tradition (the so-called non-synthesis path of the contact zone) [SHUVALOV P.V. 2012: 278].

At left: Baltic tribes before the coming of the Teutonic Order (ca. 1200 AD).

(The map from Wikipedia)

The Eastern Balts are shown in brown hues while the Western Balts are shown in green. The boundaries are approximate.

The chronicles testify that the level of socio-economic and spiritual development of the Baltic tribes in the 10th-12th centuries was lower than that of their closest neighbors.

Their economy, based on primitive agriculture in forested and marshy areas, was poorly developed and was mainly of an unproductive nature (hunting, fishing, beekeeping). The population of Lithuania at that time consisted of clearly distinguishable separate tribes; archaeology provides an idea of their socio-economic structure:

The tribal territories were small, from several hundred and to several thousand square kilometres, only several territories being bigger. The tribal territories can primarily be distinguished by the burial customs, which were diferent in each of them. But recently ever more data has emerged that the lifestyles of these tribes also difered, each having its own social and economic systems, diferent historical development, and different stages of prosperity and setbacks. Thus the development of the settlements throughout Lithuanian territory in the 1st millennium was not uniform, the form, structure, and function types of the settlements as well as the habitation system difering in the various regions (VENGALIS ROKAS. 2016: 160).

Moral norms and rituals among the population of Lithuania at that time were typical of paganism, while the Slavs had long been Christianized. Nowadays, political correctness forces us to choose expressions to characterize peoples in their past, but the information of historians of the past, being subjective, nevertheless reveals the truth, helping to restore the course of historical processes:

In their proper sense, Lithuanians dwelled in the dense forests in poverty and ignorance until the time of Gediminas. It fought off the Russian princes, and the Livonian knights with difficulty, it was always a small, weak people, and nevertheless, it could gain the upper hand over its neighbors in civil order, so that until the end of the 16th century it was constantly immersed in paganism and had no written laws. (USTRIALOV N. 1839: 33-34)

N.M. Karamzin considered the Lithuanians of the 13th century to be "courageous bandits" who were engaged "only in agriculture and war." This people "despised peaceful civil arts, but greedily sought their fruits in educated countries, and wanted to acquire them not by barter, not by trade, but with their blood." (PASHUTO V.T. 1959: 162).

In fairness, it should be noted that Moscow merchants and even embassy people occasionally engaged in robberies in Lithuania, which another Russian historian repeatedly noted in his History (SOLOVYEV S.M. 1960). According to the Russian proverb, "horseradish is no sweeter than radish". It is of great interest that, contrary to the opinion about the cultural backwardness of the Balts, there are more settlements in the Baltic habitat compared to neighboring regions. This important difference may be due to this territory's specific living conditions and historical development.(VITKŪNAS MANVYDAS, ZABIELA GINTAUTAS. 2017, 8).

In 1215, as the Hypatian Chronicle testifies, an embassy from Lithuania arrived to the Galician princes, to conclude some kind of agreement with them. The chronicle lists the names of twenty Lithuanian princes who were in the embassy. As it turns out, some of them can be interpreted using the Kurdish language:

Zhivinboud, the eldest of the princes – Kurd. jiyîn the root of the verb "to revive" and bêalt "invincible". In Ukrainian dialects, the consonant l at the end of a syllable changes into a labial-labial sound w.

Kintibout – Kurd. kîn "malice", "revenge" -tî is a word-formation suffix of an abstract concept from nouns and bêalt "invincible".

Midog – probably like Mindaugas.

Vonibout – Kurd. wanî "similar, alike", bêalt "invincible".

Boutovit – Kurd. bêalt "invincible", lêtê "to be suitable".

Bikshi – Kurd. bêhişi "madness, recklessness".

Likiiq – Kurd. weke "равный", -ek – артикль (употребляется при именах).

Vizheiq – Kurd. wêje "frank", "pure".

Vishimout – Kurd. wêje "frank", "pure", bêalt "invincible".

Half of the names of the Lithuanian princes cannot be deciphered using the Kurdish language. It can be assumed that their bearers were Lithuanians or Slavs (Davit, Dovsprounk, Dovjel, Vilikail, Erdivil, Vikjint, Kiteni, Plikosova, Sproudjic, Poukjic, Vishlii). There must have been competition between them, a struggle for influence and power. Since we have not found any Lithuanian or Slavic names among the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, success in this struggle ultimately went to the Kurds. However, the Kurds must have been a minority among the population of Lithuania, so only personal qualities could bring success to the competitors. In literature, one can find a definition of the Kurds as "knights of the East", distinguished by special militancy, courage, and bravery. However, the "chivalry" of the Kurds had a unique character:

The Kurd, of course, does not resemble the Caballero de la triste figura, hurrying to the humiliated and insulted, but… he does not disdain a dashing fun on the highway in the dark night, and sometimes in a sincere impulse he sets off to smash the infidels, not missing the opportunity to rob the weak Christian Byzantium along the way (MINORSKI V.F. 1915: 28)

This characterization of the Kurds echoes that given to the Lithuanians by Karamzin, and this is an indirect confirmation of the ethnicity of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania, with which we must agree, but the question of the time of the appearance of the Kurds in this country remains open. Let us try to find an answer to it.

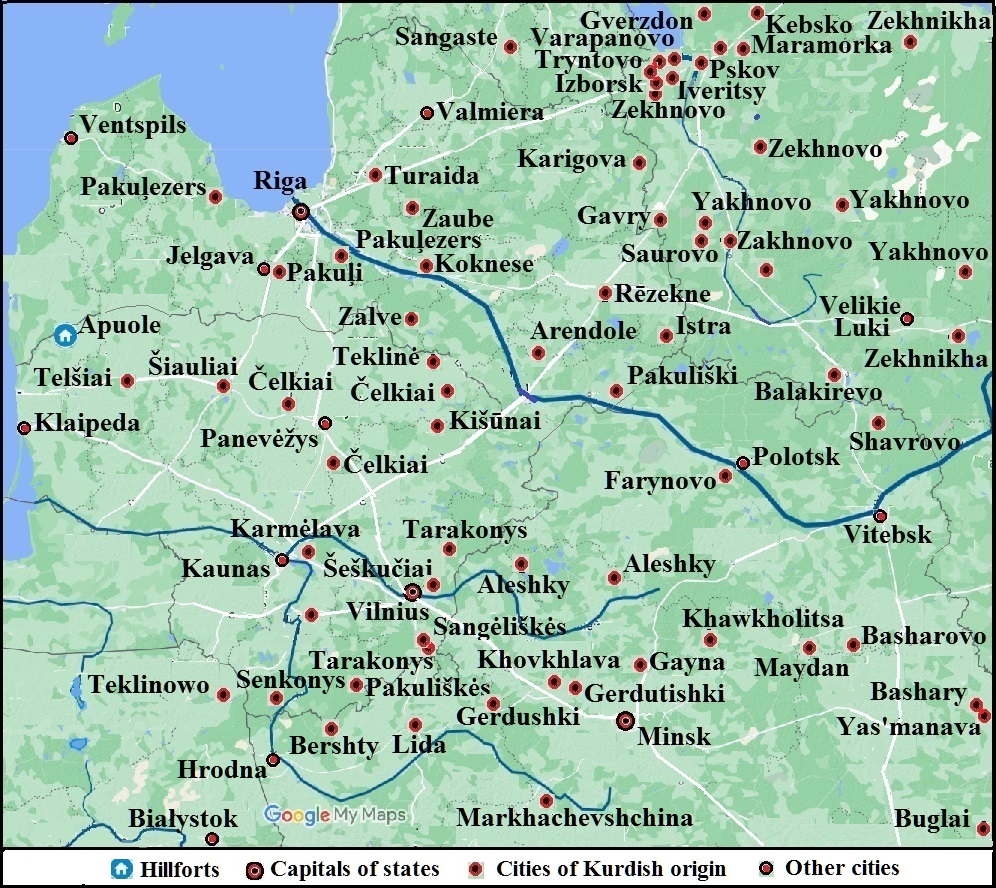

In checking Lithuanian toponymy for Kurdish affiliation, it was discovered that the cluster of supposed Kurdish place names is not located in Lithuania. Most of them were found on the southern shores of Lake Pskov and near the Pechora district of the Pskov region, Russia:

Varapanovo, a village in the Pechorsky district – Kurd. verobûn "pouring".

Vasttsy, a village in the Pechorsky district – Kurd. west "suffering, effort", "trouble".

Gverston', two villages in the Pechorsky district of the Pskov Region – Kurd. kwîr "meadow, field" or gewre "great" and stûn "pole".

Zakhnovo, six villages in the Pskov Region – Kurd. zexm “strength, power”

Zekhnovo, a village in the Pechorsky, as well as Pushkinogorsky and Ostrovsky districts of the Pskov Region – Kurd. zexm “strength, power”.

Iveritsy, a village in the Pechorsky district – Kurd. evir "swearing, cursing".

Izborsk, a village in the Pechorsky district – Kurd. izb "bachelor", "unmarried girl",ors "wedding".

Pskov, a regional center – Kurd. pezkûvî "doe".

Tryntovo, a village in the Pechorsky district – курд. torind "noble", av "wather".

The interpretation of the name Izborsk is particularly convincing. But Izborsk is mentioned in the Chronicle under the year 862 in connection with the calling of the Varangians, that is, by this time the Kurds were already far north of Lithuania.

Kurdish Toponymy in the Baltics

The map, in addition to modern cities with names of supposed Kurdish origin, also shows other major cities.

The cluster of Kurdish place names in the Pskov region corresponds to the concentration of the Long Barrow Culture (LBC) burial grounds, which makes us pay closer attention to the evidence of archaeologists about this culture. General information about it is as follows:

The Pskov LBC was formed in a vast area from Eastern Estonia to the Upper Volga and Belozerye with the participation of certain cultural impulses (possibly also groups of migrants) from the territory of Central Europe. The earliest sites of this culture do not form a single core but are scattered in several regions, including the Luga River basin and North-Eastern Prichudye. Objects found in early burial grounds still resemble things from the Roman period (MIKHAYLOVA E.R. 2017: 44).

In general, the area of distribution of long barrows covers a vast space from the shores of the Baltic to the Rybinsk Reservoir, but their density is completely different. V.V. Sedov compiled a list of sites of this culture for 1974 in the amount of 352 names (SEDOV V.V. 1974: 42-61). Unfortunately, there is no way to present the location of at least half of all the sites on Google My Maps to find patterns in their concentration. We have to use the map compiled by the author, which is not very convenient. Most of the map is given below.

Location of burial grounds with long barrows

(Ibid: Table 1).

The numbers on the map correspond to the ordinal numbers in the list of sites.

In the entire area of distribution of long barrows, V.V. Sedov identified six regions, two of which are saturated with long mounds: Sebezhskoe Poozerye with the upper reaches of the Velikaya River and the basins of Pskovskoe and Chudskoe Lakes with the lower reaches of the Velikaya River. On the map provided, they are outlined in red circles. In the basins of the indicated lakes and the lower reaches of the Velikaya River, that is, in the place of accumulation of Kurdish toponymy, there are 350 barrows, and 116 burial grounds (32.6% of the total). The question arises about the possible correlation between toponymic and archaeological data.

V.V. Sedov addressed the issue of the ethnicity of the creators of the Long Barrow culture several times (Ibid: 1981, etc.) and concluded that they were the Slavic tribe of the Krivichi. However, other major researchers, such as G.S. Lebedev, M.I. Artamonov, and I.I. Lyapushkin, did not consider the creators of the Long Barrow culture to be Slavs (ZAGORULSKIY E.M. 2014: 17). If any of the other specialists recognized the Slavic ethnicity of the Long Barrows, they still had their own opinion about the tribal affiliation of their creators (SHTYKHOV GRIGORIY. 1999: 25-33). In resolving this issue, it is quite rightly indicated that the time of the appearance of the KDK and the Slavs in the common territory of distribution should be correlated:

The chronological contiguity and territorial coincidence of the Long Barrows area with the area where the chronicler places one of the Krivichi groups gave grounds to connect the creators of LBC with the Slavic tribal union of the Krivichi. However, subsequent studies of reliably Slavic sites, new data on the time of settlement of the Long Barrows tribes by the Slavs, as well as on the dating of the early Long Barrows raise the question of the ethnic affiliation of the bearers of this culture and their attitude to the Slavic ethnos (ZAGORULSKIY E.M. 2014: 16).

E. M. Zagorulsky thoroughly criticized the supporters of the Slavic origin of the KDK, especially V. V. Sedov, but in general, his lengthy arguments were of a formal-logical nature and could not close this issue to the general agreement of archaeologists. It seems that archaeological materials without the use of additional data can be interpreted in different ways. Traditional methods do not bring success, and in the works of linguists, there is much that is far-fetched when it comes to the places of Slavic settlements.

Over time, in the process of deepening research into the culture of long barrows, a variant of the Pskov ones was identified and it was called the culture of Pskov long barrows (PLBC). However, the question of its origin is still a continuation of a long-standing discussion (MIKHAYLOVA E.R. 2018: 173). According to E.R. Mikhailova, the idea of building barrows was introduced as a result of the same cultural impulses as the things of Central European origin found in the earliest complexes of the PLBC (Ibid: 173). She believes:

The territory from which the idea of burying cremated remains in complex earthen mounds could have come to the northwest of Eastern Europe should probably be sought in the territory of the southeastern Baltics, among the Baltic cultures, where the burial mound rite has been known since the pre-Roman period. The Baltic cultures are understood to be a group of similar cultures in the territory of modern Latvia, Lithuania, the Kaliningrad region, and Northern Poland, which most researchers associate with the population that spoke languages of the Baltic group. (Ibid: 173)

E.R. Mikhailova sees common features for the Baltic antiquities and the KPDK in several aspects at once, and she especially emphasizes the large number of horse burials in both cases, as well as the burial of horse and rider equipment parts (Ibid: 173, 176). Particularly important for the topic under consideration is the location of the East Lithuanian type burial mounds close to the Pskov long burial mounds, since Kurdish toponymy extends to them from Lithuania through Latvia.

The territory of the Baltic cultures and the culture of the Pskov long barrows

Legend: 1. Territory of Baltic antiquities in the late period of peoples’ migration. 2. Territory of the Pskov long barrow culture. 3. Territory of the East Lithuanian barrow culture. 4. Dolozhsky churchyard.

(MIKHAYLOVA E.R. 2018: 174, Fig. 1)

By linking toponymy and archeology, we can assume that the location of the Dolozhsky Pogost plotted on the map may indicate that finds of PLBC sites may be found much further north, all the way to St. Petersburg and Lake Ladoga, since a chain of place names of possible Kurdish origin leads in this direction:

Shavrovo, a village in the Pskov district – Kurd. şev "night", raw "hunting".

Maramorka, a village in Karamyshevskaya volost of Pskov district of Pskov Region – Kurd. merem "goal, intention, desire", orke "empire, monarchy".

Kebsko, a village in the southwestern part of the Strugo-Krasnensky district of the Pskov Region – Kurd. kevz "moss".

Gverzton', a villages in the Pskov district – Kurd. kwîr "meadow, field" or gewre "great" and stûn "pole".

Simanskiy Logг, a village in Strugo-Krasnensky district of Pskov region – Kurd. simawî "sky, azure".

Kotoshi, a village in the Plussky district of the Pskov Region – Kurd. kutasî "finish, end".

Shevkovo, a village in Novoselskoye rural settlement of Slantsy district of Leningrad region – şewq "shine, radiance", "ray".

Samro, a village in the Luzhsky district of Leningrad Region – Kurd. sam "fear", ro 1. "солнце". 2. "to pour out, to overflow".

Rel', a village in the Osminskoye rural settlement of the Luzhsky district of Leningrad Region – Kurd. rêl "forest, grove".

Saba, a village in the Osminskoye rural settlement of the Luzhsky district of Leningrad Region – Kurd. sava "unripe", "newly formed", "small".

Lemovzha, a village in the Sabsky rural settlement of the Volosovsky district of Leningrad Region – leme-lem "turbulent flow", avşo "washing water".

Izhora, two villages in Verevskoye and Elizavetinskoye rural settlements of the Gatchina district of Leningrad Region – Kurd. îcare (ijare) "rent, lease", "payment".

Gatchina, district center in eningrad Region – Kurd. I hacet (hajet) I 1. "need", 2. "tool", 3. "way", II gacot (gajot) kirdin "to plow" (kirdin "to do, to accomplish").

Tavryавры, a village of Koltushskoye rural settlement of Vsevolozhsk district of Leningrad region – tawêr "rock", "stone, boulder".

The settlements of the PLBC have been studied much worse than the burials and mainly within the boundaries of some ancient cities, such as Polotsk, Lukoml, Pskov, Izborsk (Zagorulsky E.M.. 2014, 16). Apparently, the settlements were carried out far from the burials and their discovery was accidental. If we pay attention to the toponymy, archaeologists may be successful. According to V.V. Sedov, the second largest area of distribution of long barrows is the Sebezh Lake District (23.4% of the total). Consideration of this issue made it possible to discover an Adyghe trace in the toponymy in the area of distribution of this culture. To decipher the toponyms, the Kabardian language was used, the phonetics of which differs greatly from the Indo-European language, and this language itself could have changed significantly over time. Therefore, modern Russian names can differ significantly from the original words of the language spoken by the ancestors of the modern Adyghe peoples. Examples of Adyghe place names in the basin of the upper reaches of the Western Dvina and the Velikaya River can be the following:

Alol', villages in the Kudeverskaya volost of the Bezhanitsky district and the Alolskaya volost of the Pustoshkinsky district of the Pskov region, a river, a tributary of the Velikaya River – Kabard. lale "sluggish, weak", -a – a prosthetic vowel.

Velizh, a city, administrative center of Velizhsky district of Smolensk region – Kabard. ueliy "ruler, master" (from Akkadian) -zh' – a suffix on a noun that intensifies its meaning.

Vyar'movo a village in the Krasnogorodsky district of Pskov Region. – Kabard. uerem "street".

Zhadro, a village in Zvonskaya volost, Opochetsky district, Pskov Region – Kабард. zhad "chicken, han", -ru – the objective case suffix.

Zhiguli, villages in the Verkhnedvinsky district of Vitebsk Region (Belarus) and in the Kunyinsky district of Pskov Кegion – Kabaed. zhygeile "an area covered with oak trees". Zhuguli on the Volga is of the same origin.

Komsha, a village in the Velikoluksky district of Pskov Region. – Kabard. gumashchIe "kind-hearted, merciful."

Kurmeli, a village in the Velizhsky district of the Smolensk region – Kabard. kurme "a knot at the end of a string", -le – noun suffix.

Opochka, a city, administrative center of Opochetsky district of Pskov Region – Kabard. upIshkкIya "crumpled".

Reble, a village in the Pustoshkinsky district of Pskov Region – Kabard. eru "fierce, cruel", ble "snake".

Sebezh, a city, center of the urban settlement of the Pskov Region – Kabard. sabe "dust" -zh' – a suffix on a noun that intensifies its meaning.

Tekhomichi, a village in Sebezhsky district of Pskov Region – Kabard. tkhe "god", myshche "bear".

Usmyn', a village in the Kuninsky district of the Pskov region – Kabard. ues "snow", myin "small, lttle".

As the toponymy decipherment shows, the builders of the long barrows in the Sebezh Lake District must have been an Adyghe tribe. Archaeologists see characteristic differences between this group and the Kurdish sites near Lake Pskov and Lake Peipus. Based on this, we can assume that the creators of the different cultures of the long barrows that existed in the 5th-11th centuries were people from the Bosporan Kingdom during its decline. In the 5th century AD, the first fortifications of the oldest castle in the Baltic, Apuole, were burned down and subsequently rebuilt. In the 7th century, the fortifications burned down again (VITKŪNAS MANVYDAS, ZABIELA GINTAUTAS. 2017: 43). These events can be assumed to correspond to the time of the appearance of the Kurds. Apuole continues the chain of Kurdish place names (see the map above). According to the Bremen Archbishop Rimbert, the castle was attacked by Swedish Vikings in 853 (ibid: 41). During the following centuries, the Kurds peacefully coexisted with the autochthons of the Eastern Baltic, which from the time of Vladimir Svyatoslavich (reigned 978-1015) and throughout the eleventh century, and to a lesser extent from the first half of the tenth, was under pressure from Rus' (BARANAUSKAS TOMAS. 2002, 106). However, under the threat of the Teutonic Order seizing the entire territory, the Kurdish princes from the Pskov region crossed the Daugava consolidated the local tribes under the rule of one of their leaders, and established a xenocracy in the country. This circumstance laid the foundation for the creation of the Lithuanian state. As for the Adyghe, judging by the location of their monuments in the Sebezh Lake District close to the Latgalian settlements, they could have played some role in the history of Latvia.

In conclusion, it should be agreed that the Lithuanians may not like the fact of the direct participation of an alien tribe in the creation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This once again proves that people do not always like the truth and it is not always useful. This feature of human psychology was noted by Thomas Eliot Stearns, the poet and essayist: “Humankind cannot bear very much reality” [ELIOT T.S.]