Sketch on the Development of Merchandise in Central and Eastern Europe at Prehistoric Times

Exchange is interesting because it is the chief means

by which useful things move from one person to another;

because it is an important way in which people create

and maintain social hierarchy; because it is a richly symbolic activity – all exchanges have got social meaning…

Exchange is also often fun: it can be exhilarating as well as useful,

and people get excitement from the exercise

of their ingenuity in exchange at least as much because of the symbolic

and social aspects as because of the material changes which may result [DAVIS J. 1992: 1]

Historical pieces of evidence, which would allow judging the state of the inter-tribal trade in prehistoric times, are extremely scanty. Still, archaeological finds, among which there are objects obtained or manufactured in distant places, show that in Europe and Asia as early as the late Neolithic and Bronze Age exchange trade was already quite widespread and represented one of the aspects of the development of human civilization. Moreover, in some primitive form, trade relations between hunter-gatherers and emerging agricultural societies already existed in the Mesolithic:

…it seems well possible that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers travelled longer distances into ‘farming country’ to establish and maintain contact and trading networks. This helps us break up the top-down approaches, which see hunter-gatherer groups as simple ‘receivers’ of Neolithic goods and ideas [HOFMANN DANIELA, PEETERS HANS and MEYER ANN-KATRIN. 2022: 279].

Cited Authors, considering the role of migration in the uptake of the Neolithic to tease out the social processes and complexities, talk about trading networks as if it were a self-evident phenomenon. However, there must be reasons and conditions for migration. According to Radan Květ, following in the footsteps of Mandelbrot, the hydrological network configuration on our planet is predetermined by geological faults, a phenomenon of fundamental importance. A network of prehistoric paths connected to the hydrological network provided physical facilities for migration and hence trade (KVĚT RADAN. 2000: 294). However, archeology cannot name the reason for the emergence of this form of social activity. The reasons can be understood by analyzing the historical development of trade, leading to the following conclusion:

Trade may seem a very pragmatic activity, one that needs no fictive basis. Yet the fact is that no animal other than Sapiens engages in trade, and all Sapiens trade networks were based on fiction. Trade cannot exist without trust, and it is very difficult to trust strangers. The global trade network of today is based on our trust in such fictional entities as currencies, banks, and corporations. When two strangers in a tribal society want to trade, they establish trust by appealing to a common god, mythical ancestor, or totem animal. In modern society, currency notes usually display religious images, revered ancestors, and corporate totems (HARARI Yu.N. 2016: 52).

Trust is an unprecedented achievement resulting from the cognitive revolution of Homo sapiens that archeology bears witness to. Archeology also gives us an idea, although incomplete, of the composition of goods and their parts in the entire volume of trade relations. Perishable products fall out of the list of popular goods so some conclusions may be hypothetical. For example, the exchange of food products must have existed, so we can assume that it was local due to transportation difficulties, although it should have been the most ancient. Good traces were left by hard goods (flint, ceramics, metal products, shells, horn products, bones, and amber). The quality of communications and the development of technologies for moving goods (carts, sleighs, boats) were of great importance for developing trade. The connection between trade and civilization topic has a great theoretical interest and many works of specialists are devoted to it (DAVIS J. 1992, SHERRAT SUSAN and ANDREW. 1993, PYDYN A. 1999). At the same time, the understanding of the nature of trade changes substantially in proportion to receiving new historical evidence. The range of issues that arise when considering the connection between trade and civilization is quite wide. Among them are: How do the trade institutions relate to political power? Is trade a prerequisite for making stable political structures, or vice versa? What is the relationship between trade and a predatory economy and between trade and war? Under what circumstances could trade networks promote religion, art, and ideology dissemination? etc. (KRISTIANSEN KRISTIAN, 2018: 1-3). Such questions are important for understanding the patterns of the development of human civilization but unambiguous answers cannot be obtained if the ethnic component of the trade processes is ignored.

Trade developed from the simple exchange of necessary items between people which led to the accumulation of wealth from individuals. The nature of people's pursuit of wealth question is a separate and complex topic that specialists should deal with. Earlier than others, even some Marxist philosophers realized that the overestimation of material interest in human life is fraught with a certain threat to society:

The desire for wealth, embracing individuals and entire nations, leads to the opposite result – decay and death (Giambattista Vico, cited from LIFSHITS MIKH. 1994, X).

For suppressing the feelings of fear that are constantly present in the life of a primitive man, not material values that were, in principle, possible to satisfy, but psychological comfort that could be provided only by spiritual values were more important. The network at the same time served as a means of exchange not only and not so much with goods, but as an opportunity for the exchange of information between distant human collectives:

In the history of mankind, the original network of paths became the first information network. It did not have the main goal of trade and military relations: all kinds of technological experience, as, of course, a cultural one, led to the unity of thoughts, ideas, philosophical and religious views, just as well as artistic tastes (KVĔT R., 1998: 43).

Modern philosophers also agree that material values do not provide a person with peace of mind in our time:

Ultimately, the main price for a consumer society is the feeling of general insecurity that it generates (BAUDRILLARD JEAN. 2006: 46).

Based on this point of view, in this presentation we will assume that both in prehistoric and in our time, providing people with the necessary goods is not a goal, but a means of achieving it.

The first exchange goods were products of mineral and rock formations, passed from hand to hand at ranges in the hundreds and even thousands of kilometers, as raw materials could not be found everywhere. The most common were flint and obsidian tools and weapons and to a lesser extent products of quartzite, diorite, and jade. The exchange trade with flint products corresponds to the distribution of artifacts from the Funnel Beaker culture. Products made from different types of flint, such as silver pieces, blades, axes, etc. were made from original local raw materials in the area of Krakow, Radom, and Krzemenok in Poland, Rügen in Germany, and Volyn, but were located throughout the entire area of distribution of this culture. Residents of dwellings located far from sources of raw materials used more advanced tools than at production sites. Interestingly having local raw materials does not exclude residents’ interest in tools made from other “exotic materials” (MILISAUSKAs SARUNAS. 2002, 215-216).

Minerals with decorative qualities, such as lapis lazuli, malachite, agate, and carnelian, were used for jewelry; women's jewelry was one of the oldest exchange goods.

At right:Cowrie shells, Photo from the site"Cowrie shells – first money.

This primarily refers to the attractive and shining shells, which have been used by women of those times for neck jewelry. The shells, which could be found only on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, got into quite a large number of people in Central Europe still 30 thousand years ago (KRÄMER Walter, 1971, 46). The shells were used even as payment means in some places. Certain types of shells were of great value and the attitude towards them reflected the peculiarities of the worldview of primitive people:

In prehistoric societies, prestige and social value were given to very select objects. For example, local communities from the region near the mouth of the Vistula River could easily have obtained many different types of shells but instead chose to give a high value only to a specific type of cowrie shell which had to be obtained from the Mediterranean or the Black Sea. These shells could only be acquired through long-distance exchange, so knowledge about them was very fragmented and places of origin were unknown. The cowries trade was easy to monopolize and control. It is also characteristic that cowrie shells, in contrast to most of the southern imports that have been found in the northern part of Europe, did not have added or technological value. Their high value was directly related to a gap in knowledge which separated their place of origin and the northern communities in which they were used. Furthermore, the significance of these shells might have been increased by the potential symbolism of their shape, which could represent a vagina. Shells often carry this fertility symbolism in many different parts of the world (PYDYN A. 1999).

Due to their visual appeal, gold and silver nuggets were also used for jewelry. As rare things, they were in great demand and were highly valued. The ease of processing precious metals has made using them in human creative activities possible. In excavations of ancient burials, archaeologists find gold and silver pendants, earrings, beads, bracelets, etc. Native copper was also used for the same purpose, but as a harder material, it was used to manufacture tools and weapons. The spread of such products through trade ushered in the onset of the Copper Age in human history, and tin also became a commodity during the Bronze Age. Copper and tin were used to make bronze in large quantities everywhere. In Central Europe, copper ore deposits are scattered in small deposits across different regions, but most of the copper ore came from two mountainous regions – the Alpine and the Carpathian. Tin was also mined only in minimal areas in the Ore Mountains of Germany, Bohemia, and Silesia (Ibid) — the search for new deposits led to new geographical discoveries.

From its inception, trade evolved in line with changes in the social structure of tribal societies, and traded goods reflected these changes. The initially predominantly unilinear evolution of social processes became more complex, and archaeology has noted major changes in centuries-old trends since the fifth millennium BC (HOFMANN DANIELA and GLESER RALF. 2019: 14). These changes are varied and affect the sphere of trade:

The fifth millennium also sees the beginnings of the circulation of so-called prestige goods, namely jadeitite and copper. These items are often interpreted as the prerogative of an elite99, creating a kind of distributed community of high status individuals with — at least implicitly — similar social strategies and goals. In the case of copper, the appearance of such artefacts and the techniques of their production, alongside the circumstances of their use, are sometimes thought to mark an elusive “new epoch” associated with a package of social, economic and religious innovations, even in central Europe (Ibid. 2019: 29-30).

As expected, cultural influences on Central and Eastern Europe came from the cradle of human civilization in the Middle East. On trade routes formed as a result of tribal trade during the Neolithic, cultural and everyday objects from Palestine and Syria along the eastern and northern shores of the Mediterranean Sea:

Westward maritime traffic followed the south Anatolian coast from Cyprus to Rhodes, and then could either cycle anti-clockwise around the Aegean or continue westwards in two streams: either along the southern margin, through Crete and up the west coast of Greece to cross to southern Italy and Sicily, or through the Cyclades to Euboea and Attica. Here an alternative westward route was possible for small ships using the isthmus of Corinth to avoid the dangerous circuit of Cape Malea in the southern Peloponnese (SHERRAT SUSAN and ANDREW. 2012: 367)

Through the islands of the Aegean Sea, the Vardar and Great Morava rivers wares came into the Middle Danube Basin. Together with everyday goods, technological experience and creative tastes spread. According to Gimbutas, almost all the archaeological artifacts of the cultures of Central Europe had prototypes or analogs in Egypt, Northern Iran, on the Syrian-Palestinian coast, and in Cyprus:

These are neck rings with rolled ends, curved shank pins with knot heads, called Cypriote pins, or with simple spiral or loop heads, sheet-metal belt plates with rolled ends and embossed decoration, cylinders wound of thin copper wire, double-wire spiral rings, earrings with flattened ends, plain spiral bracelets, and double-spiral pendants. (GIMBUTAS MARIJA. 1965: 32).

Not only archaeological findings, but also the study of the peoples' vocabulary, places dwellings which we know from the research, can be of great help in the coverage of this topic, and the last is dedicated to making this essay. However, we take as the starting point of this essay reliable pieces of evidence of ancient, primarily by Herodotus:

These are the extremities in Asia and Libya; but as to the extremities of Europe towards the West, I am not able to speak with certainty: for neither do I accept the tale that there is a river called in Barbarian tongue Eridanos, flowing into the sea which lies towards the North Wind, whence it is said that amber comes; nor do I know of the real existence of Κασσιτερίδας, "Tin Islands" ( from which tin comes to us: for first the name Eridanos itself declares that it is Hellenic and that it does not belong to a Barbarian speech, but was invented by some poet; and secondly I am not able to hear from anyone who has been an eye-witness, though I took pains to discover this, that there is a sea on the other side of Europe. However, that may be, tin and amber certainly come to us from the extremity of Europe. (HERODOTUS. III, 115)

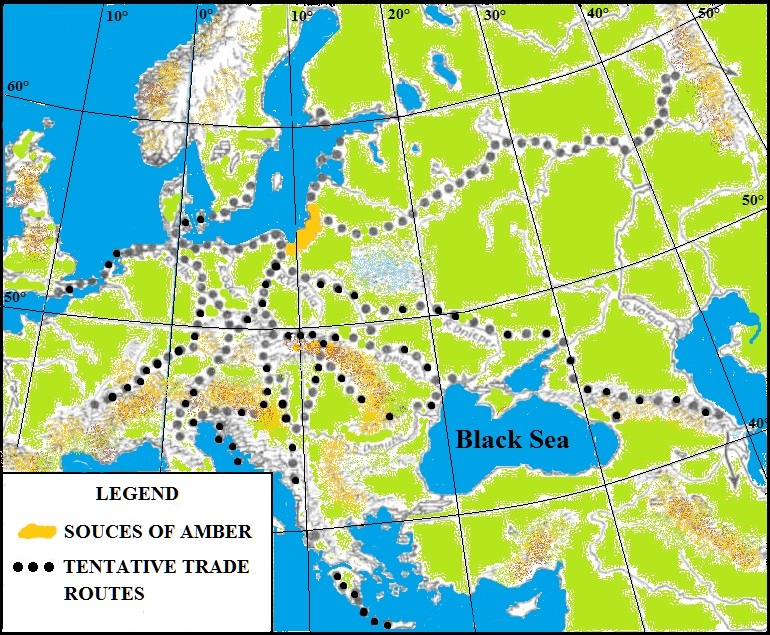

What is this river Eridanus not clear so far, but Cassideridas – this is obvious, the British Isles, wherein those days deposits of tin were discovered and guided its development for export. Trafficking of this metal needed for the production of bronze was engaged by Phoenician sailors, and they concealed the true location of these islands. Also, you can think of, traders of amber concealed locations in the country where there were large deposits of this fossilized resin of coniferous trees. However, the Greek navigator Pytheas, who visited the Jutland peninsula in 325 BC, argued there was so much amber that the locals used it as fuel instead of wood. At the same time, it is well known that most of them are located on the coast of the Baltic Sea and, therefore, at least one of the ways of amber trading had to be in Eastern Europe. It is believed that it started east of the mouth of the Vistula, and then followed this river to the Upper Oder, crossing the Moravian gate between the Sudeten and the Carpathian Mountains, overlooking the Hungarian Plain (Great Plain) and further along the Danube reached Greece (KRÄMER WALTER, 1979: 185-186). However, the nearer way was over the Vistula and on the Western Bug, or San, and then on the Dniester to the Black Sea. Another way went along the Vistula River and further along the Western Bug or San rivers, and then along the Dniester reached the Black Sea. However, Marija Gimbutas claimed that back in the 14th century BC amber reached the shores of the Caspian Sea, so there could also exist a trade route from Central Europe through the Pontic area to the North Caucasus (GIMBUTAS NARIJA. 1965: 88).

Left: Amber routes during the period between ca 1600 BC and 11600 BC.

The map was compiled after (Marija Gimbetas. 1965: Fig 1, p. 49 Johannes Richter)

In the Days of Yore, intertribal merchandise has evolved as a consequence of the availability of excessive production of a certain type by different groups of people and the lack of or insufficient amount of other types of products, the need for which has been pressing.

Changing redundant things to lacking ones is a natural action among people of the same community, and this practice has been applied in relations between different ethnic groups, even if there was a certain lack of confidence. In such circumstances, the so-called "silent trade" was developed when customers left their goods at a particular place and went to a safe distance, the buyers came up for them and left instead the equivalent goods, in their opinion, for the obtained ones. Abuse of trust entailed a break of "trade intercourse", in which nobody was interested. The presence of certain goods in certain places and their absence in others, as well as geographical conditions, led to the emergence of trade routes, but not yet to the emergence of a class of people who were engaged in merchandise professionally but this is gradually gaining new forms and heavily promoted cultural exchange:

Of course, the goods were transferred to such long distances, not by individual merchants, they were passed in the exchange from hand to hand, from village to village, from country to country. However, the exchange trade itself resulted, at least, in the contacts with the neighboring regions, and thus the first information about distant lands and peoples could be passed on. It is even possible that individual traders then moved further than we can now imagine (KRÄMER WALTER, 1961, 13).

Since the tin deposits in Eastern Europe were absent, pay attention to the other items mentioned by Herodotus – amber. As early as the 6th mill BC, it was used for jewelry among the peoples of Northern Europe, and from the 16th century BC such ornaments were found in the tombs of Mycenae and the early state of Urartu. The regular supply of amber from the eastern Baltic to Greece and Asia Minor begins at about 900 BC (KRÄMER WALTER, 1979, 184, 186).

Amber was used for making necklaces, earrings, pendants, etc.

Right: Amber ring pendants. (Photo from the pageВсе о янтаре.

The characteristic shapes of the jewelry and the percentage of succinic acid make it possible to determine trade routes from the place of mining to consumers. The richest deposits of amber are in East Prussia and Lithuania. Still, products from it were found not only in Greece but also in southern Italy, Sicily, and Iberia (Gimbutas Marija. 1965, 48).

We know that the Proto-Chuvashes were the creators of the Corded Ware and battle-axes culture, and one of its variants was spread in the Baltic States (Vistula-Neman, or Rzucewo culture). The Proto-Chuavshes also inhabited the main trade routes along the Vistula and Dniester, so could have a monopoly in the production and trade of amber. In this connection, will try to find in the Chuvash language words which would mean an interesting subject. Two very similar words were found yantar and yantar'. The second word, of course, was borrowed from Russian and means just "amber". The first word, the more ancient, and now obsolete, meaning "glass" is semantically close to the name of amber, and such sense is secondary. Other languages, the speakers of ancestors of which would have to deal with amber (primarily Estonians and Finns) have no similar words. The remote match to Estonian and Finnish names (Finn meripihka "marine resin", Est pihkakivi "resin stone") can be found only in the Udmurt and Komi languages where the fossilized resin is called stone resin. Other Finno-Ugric peoples use loanwords for the name of amber of completely different origins. This suggests that the ancestors of the Estonians and Finns, just like other modern Baltic peoples came to the shores of the Baltic Sea considerably later than Proto-Chuvashes. In this regard, one might think that Chuv. yantar can be close to the original name, which versions are presented in different languages.

The origin of the Russian word yantar', which was also loaned in the Belarusian and Ukrainian languages, is unknown. Lit gintaras, Let. dzintars "amber", Hung. gyanta, gyantar "tree resin, amber, rosin", Mari yanda "glass", yandar "clear" are phonetically similar to the Russian word. Having reviewed all these names, B.A Larin concluded that the Baltic words were borrowed from an unknown ancient language, the name of amber in the form yentar came from the Baltic languages to Russian, Mari words were borrowed from Chuvash, and Hungarian forms with diverse values indicate their greater proximity to the initial forms of an original language (LARIN B.A., 1959). Since the closeness between the Hungarian and Chuvash languages is known, the choice of a search way for etymologizing using the Chuvash language looks promising and, indeed, we find in the dictionary Chuv. ĕnt "to burn, singe," which can be taken as the part of a compound word for the name of amber. The reason for such an assumption gives available German word Bernstein denoting amber as a "combustible stone". Recall that the Teutons, the ancestors of the Germans were northern neighbors of the Proto-Chuvashes. In this case, the second part of the word yentar should mean "a stone". Chuvash called stone chul having the common for all Turkic languages protoform *taĺ (in most of Turkic taš). Thus, the "combustible stone" in the Proto-Chuvash language could be called enttal, wherefrom is not far from the modern name. However, the existence of Mari and Hungarian truncated forms of the name of amber suggests that the word enta could be used, meaning simply "flammable". However, these words are borrowed in the Mari and Hungarian languages from Chuvash.

According to our study, the Urheimat of the Slavs was near the amber deposits on the shores of the Baltic Sea, and later some of the Slavic tribes were dwelling on its shores, so amber would be known to them and they had to have a common Slavic name for it, but its traces meanwhile were not found. The Slavs appeared on the Baltic Sea shore after the split of the Slavonic Community. Acquainted with amber, Slavs used to call amber calque from Proto-Chuvash, not without reason that the phrasing "white-combustible stone" exists in Russians that for no other stone, except amber, will not work.

Export goods of Slavs could be wax and honey because they have long practiced beekeeping. Less confident we can talk about the furs, as ancient Slavs were more fisher as a hunter. Therefore, Slavs could have for the sale of fish. However, such a perishable commodity was not interesting for the nearest neighbors, being also abundant in fish resources, but to transport fish over long distances would need to use a preservative, which could be salt.

Salt, without a doubt, was one of the first merchandise, as its deposits were not everywhere, but during the Neolithic role of plant foods in the human diet was increasing and the need for salt was also increased. However, salt has different uses in human life:

Since ancient times, salt was the main preservative of key foods (meat, fish, cheese). This mineral has removed the man's dependence on the seasonal availability of food and made it available to travel considerable distances. Salt is also a multifunctional medicine for people and livestock. It was involved in the technology. In particular, salt is used as one of the key components in leatherworking. Similarly, in religious rituals in many cultures, salt is an important attribute that symbolizes friendship and incorruptible purity, because of what appears in the funeral and wedding ceremonies (BOLTRYK Yu.V. 2014, 63-64).

It is a common custom among the peoples of Eastern Europe to give a loaf of bread and salt shaker on it to the honored guests. But the very greeting of bread and salt, which is a calque of Chuv. çăkăr-tăvar, is common in the everyday life of the Slavs:

The greeting of visitors in peasant societies with bread and salt (khlyeb i sol), and its variants in the different Slavic languages reflect the important role played by these two items: bread as the “staff of life” (the basic foodstuff), and salt as the symbol of well-being (HARDING A., 2013: 13).

Other subjects of exchange were livestock, dried and salted fish, tools, and handicrafts. This is evidenced by existing in the Turkic languages of western areas and the language of their neighboring people words of different meanings but being united by common value "goods, the subject of the exchange." Just this word is tovar and the similar ones meaning "commodity". It has the form tavar in the Armenian language and means "sheep", or "flock", the Turkic languages have such words: Kum tuuar "herd", Turk. tavar "property", "cattle", Balk., Cr. Tat tu'ar "property", Chuv tăvar "salt", tavăr "to return the debt", "revenge", "meet", "turn out", etc. Chuvash words are very illustrative. The Proto-Chuvashes had the opportunity to extract salt because they inhabited the area close to the Sivash Bay. Although the salt obtained from seawater or sludge has a bitter taste, some technologies make it possible to get rid of this drawback (ibid 2013: 28). The Proto-Chuvashes mastered handicraft, which provided them with salt as an export item, therefore it acquired the meaning of “commodity”. The Second Chuvash word tavăr phonetically and semantically is a bit further. But in principle at first, it could mean "to pay back", or "to offset" that are semantically close to "price" which could develop from meaning "goods of exchange". Many Iranian languages have the word tabar / teber / tevir "an ax", and Finno-Ugric similar words mean "textile" (Saam. tavyar, Mari tuvyr, Khanty tagar). They all have the same origin, as both tools, as well as production have been the subject of trade. Maybe Slav tur "aurochs", Lat. taurus and Gr. τυροσ, "bull" could be included here, although competent professionals (Vasmer, Walde and Hofmann, Menges) are silent about such relationships. Finally, this word can be attributed to such Germanic words of unknown origin: Ger teuer, Dt duur "expensive", Eng dear.

As this name of goods so clearly revealed its antiquity, it is possible to raise the question about the search for traces in modern languages a word for the process meaning the equivalent exchange of goods. We can trace the etymology of the words have the value "trade", "price", "to buy", "to sell", "to cost", "dear", "cheap" etc. But many of them have no matches in other languages, but correspondences are available just for the word torg and similar "merchandise". According to M. Vasmer, Slavic *tŭrgŭ presented in different ways in all Slavic languages have cognates words also in Lithuanian, Latvian, Illyrian, Albanian, Swedish, Danish, Finnish, and others (VASMER MAX. 1973. V IV: 82). The root of this word can have front and back vowels and, labialized and not labialized what, in fact, points to the itinerant character of the word – torg-, turg, targ-, tirg-, terg-. The origin of the Slavic word *tŭrgŭ was clarified by G.I. Ramstedt and M. Räsänen. According to Ramstedt, Turkic words meaning "silk" and in general "fabric", and "goods" were borrowed from the Mongolian language (Mong. torga "silk", Tung. tōrga "cotton fabric", "goods") and further in other similar meanings spread to Scandinavia (RAMSTEDT G.J. 1949: 99; RAMSTEDT G.J. 1957: 49). On the contrary, Räsänen considered Trc. turku, turγu "station" to be the original (A. RÄSÄNEN M. 1946: 82), although he did not return to this thought later, limiting itself to mentioning the Turkic-Mongolian matches in the name of silk (RÄSÄNEN M. 1969: 490).

Trade places had to be certain so those who wished to exchange goods could easily find a counterpart. They are mainly based on geographical conditions, taking into account the convenience of the area, and the availability of drinking water sources at the intersection of communication routes. Understanding the peculiarities of trade organization gave grounds to put it as the basis of a purely materialistic logistics theory of modern civilization (SHKURIN I.Yu. 2013). From the point of view of logistics, the shores at crossings, the mouths of river tributaries, where both sellers and buyers could easily reach, were well suited for shopping centers, where permanent settlements arose:

…location of late Neolithic settlements may also testify about the possible ways of applying by local community control over natural crossings, therefore, for ways to move and intertribal exchange, which gave them an advantage in social development and the opportunity to expand their influence (TOVKAYLO M.T. 1998:14).

Besides O.T. turku, formed from tur-"to stand", "to be", and "to live", which has matches in many Turkic languages, can also consider other words suitable for our situation: O.T.. tera "valley lowland", 1. terkäš "confluence of river branches"; Yakut. törüt "river mouth". It is natural that in such markets there has been a large crowd of people, and this is also reflected in the Turkic languages: O.T. ter "to collect, hoard"; terig "meeting, gathering"; törkün "tribe", O.T. terkäš "crush"; Tat. törkem "crowd, group"; Bash. törköm "crowd"; Balk., Karach. türtüšou "crush"; Tur. türük, "kingdom, world", teraküm "accumulation". It was also natural tension between sellers and buyers, the first tried to sell their goods more profitable, the latter, trying to bring down the price, argued, scolded, were capricious, that was traded. Such a conclusion can be reached by considering the following words: Chuv. tirke "be picky", tirkev "capriciousness, fastidiousness", Tur terk "abandonment, rejection, repudiation", diriğ "refusal", O.T. terkiš "grumpy", Tat. tirgərgə "to scold", Bash. tirgəü "curse". The contradictions between the seller and the buyer is also displayed by the etymology of the ancient Indo-European word *kʷrinā- "to buy" (OInd krīṇāti, Gr. πρίαμαι, NPers. xarīdan, OIrl. cren-, OLyt. krieno and other similar). This word originates from Proto-Chuvash *keren "to be stubborn, to balk" (Chuv. xirĕn). Likewise PIE. mizdhō "payment" can have Proto-Chuavash origin too (OSlav. mьzda, Osset. mizd, Got. mizdō a.o.), if the word is derived from the question of the buyer "how much"? Chuv. miçe "how?" and tav "thank" corresponds such question.

Noteworthy is to say the root *torg is presented in languages whose speakers were living on the right bank of the Dnieper River in the 2nd mill BC. The Greek, Latin, Celtic, Iranian, and Indian languages don't have it. Therefore, we can assume that the source of the word was the Proto-Chuvash language but not other Turkic people's language populated land on the left bank. Considering Chuv. turkhan with OT tarqan "privileged person title", it can be restored as *turk? with a meaning associated with the trade. The city of Turka has a similar name in the Carpathians, where many place names are deciphered using the Chuvash language. The antiquity of this town can be confirmed by the message of Constantine Porphyrogenitus on white Croats living "beyond Turkia in the land called them Boyki" (CONSTANTINE PORPHYROGENITIUS. 1961: 32). It is believed that the land Turkia has to be understood as Hungary, and the Boyki is one of the Celtic tribes. One does not exclude the other because Hungary is located not far from Turki. The entire territory nearby could be called by the city name. Turka is now considered to be the "capital" of the Boyki, one of the tribes of the Carpathian Ukrainians, so one might think that this ethnonym they had inherited from the Celts. The transfer of the ethnonyms from one tribe to another is a common occurrence in history. And due to its convenient location on the way from Hungary to Galicia Turka could play the role of the merchant center. It was not for nothing that nine large fairs a year were held here in the 18th century (PULNAROWICZ WŁADYSŁAW. 1929: 29). It is commonly believed that the name origins from Ukr tour "aurochs", but this explanation seems questionable since the motivation giving word suffix -ka is unclear. In addition, in Ukraine, there is the village of Turka in the Ivano-Frankivsk region and even three villages of the same name in the Lublin Voivodeship of Poland, ten villages of Turkovo in Russia, and one in Belarus, the city of Turku in Finland, Turkeve in Hungary, Turkov in Germany. It is difficult to assume that all these toponyms come from the word tour, so it would be necessary to look for different explanations for them, while a more plausible interpretation is to interpret them all as “marketplace”, which is very suitable for a populated area.

Although food as a commodity has left little trace in archaeology, burnt grains indicate that cereals may have been traded items. Also in the vocabulary of the languages of different peoples, there remains some evidence of participation in intertribal food products. At the same time, borrowed words traveled around the world along with the product itself. This allows us to see grain, leather, furs, and drinks among the items of exchange and trade in addition to the mentioned wax and honey. If we talk about grain, then first of all we need to name barley, millet, and oats, but it is typical to transfer the name from one cereal to another. For example, Trc dary "millet", which is borrowed in Hungarian and Mari, can be associated with Georg keri "barley", and Trc. sulu / sula / suly "oats" with Georg svili "rye". Trc. arpa "barley", which has exact matches in gr. αλφι and alb. el'p, was adopted in Germanic as "pea" (Germ. *arwa - Ger Erbse). If the grain trade and, therefore, the spread of cereals went from south to north, the leather, furs, wax, and honey came into the southern lands from the north. At least the Turkic people gained honey and wax from their northern neighbors Italics and ancient Armenians, as evidenced by correspondence Trc. bal "honey" – Lat. mel, Arm. mełr "honey". Sir Gerard Clauson wrote on the origin of the Turkic name for honey:

It is generally accepted that this word is a very early borrowing from some Indo-European language, which can be dated by a period when m was unacceptable at the beginning of words, and therefore was replaced by b (CLAUSON GERARD. 2002.)

Another commodity that left no material traces was slaves. With the development of city-states, a new economic system began to develop. The institution of slavery, which existed previously, turned into a productive force and source of profit in the hands of slave owners:

These developments altered the nature of slavery, which increasingly took the form of chattel slavery alongside the forms of household ('patriarchal') slavery practised earlier. Slaves became a commodity traded in large numbers and were applied to large-scale construction and industrial works, including agricultural work and mining. Slave populations might now be ethnically distinctive, often brought from considerable distances (SHERRAT SUSAN and ANDREW. 2012: 363).

In the process of a spontaneous search for a universal equivalent in trade, people began to consider gold and silver as such. Acting initially as ordinary goods, these metals began to perform the basic functions of money everywhere. The etymology of the names of silver among different peoples confirms this assumption. For example, common in many Iranian languages the word arg/arz and having the basic meaning "price", comes from the name of silver (Lat. argentun, Av. ərəzata- a.o.) Another example would be the Turkic word kümüĺ (Chuv. kěměl) "silver" which seems to have been borrowed by Turkic people from Trypillians, which language we have identified as Semitic. Trypillian and Turkic settlements were divided by the Dnieper River, which, especially in the winter, could not be an insurmountable obstacle to neighbors, so the primitive trade and cultural exchange between the Turkic people and Trypillians took place. Traces of Tripillian influences on the merchandise are found among words meaning "product", and "payment", which we discussed above, cf. Heb. davar "a word", "a thing", "something". Trypillians could also have the word *kemel, corresponding to Heb. gemel "to give back" which we associate with Chuv kěměl "silver" ( See the article The Names of Metals in the Turkic and Indo-European Languages). Since silver served as money, the change in the meaning of this word among the Turkic people is because the trading parties did it without a translator and therefore could give different meanings to the same object. What was simply pay for one, took for another persona particular value of silver. This word was borrowed from the Proto-Chuvashes by Italics and used for naming silverware, particularly silver dishes (Latin caměl-la "plate of soup").

Another word, which meant "payment, price" and loaned by Turkic people from Trypillians, could be the word *demirz, which corresponded to the Heb. demis "money." Modern-day Turkic words demir / temir mean "iron" and it raises doubts about the possibility of the use of iron as a means of payment when this function belonged to silver. In addition, iron was not yet known at the time of contact between Turkic people and Trypillians. However, it could be assumed that for a long time Turkic word *demirz was used just in the general meaning of a costly thing, and only later, with the advent of the first iron products, which, indeed, had great value, changed its meaning. It is also possible that the word was first taken from the Turkic people to "copper", because, after the appearance of copper, it could also run as money of minor value.

This more affordable and suitable for different household crafts metal was found during the search for noble metals in nature, together with whom it was often present in deposits. The advantages of copper and later bronze replaced stone tools were appreciated by people very quickly, but the possibility of getting metals from the earth was not everywhere. Therefore, the need for copper was covered by exchange for other goods. The population placed rich in copper deposits began to specialize in the production for its profitable exchange. In Eastern Europe, such a place was the Carpathians:

The Copper Age was characterized by the forming of the Balkan-Carpathian Metallurgical Province. This system of related manufacturing hotbeds occupied mining and metallurgical centers of the Northern Balkans and Carpathians, where extremely bright farming and animal husbandry Eneolithic cultures of Gumelniţa–Karanovo, Vancea-Pločnik, Tisapolgar-Bodrogkerestur, Petreşti were localized. Widely known Trypilla culture in the southwest of the USSR was only the eastern province of the block and did not know their own industry: its masters used imported copper. Since the formation of the province, a large proportion of products from the Balkan and Carpathian centers was sent further to the east in the Eastern European Steppe and Steppe-Forest (CHERNYKH E.N., KUZMINYKH S.V. 1990: 136).

It is understood that the function of money could act as metal ingots of a certain weight. Archaeology does not yet have the data on when a balance in Eastern Europe appeared, but the possibility of its existence was cloudily testified by linguistics. For example Mari punda "money" corresponds to OE.. pund "pound, as a measure of weight". Maybe the word came to the Mari language through Mordvinic which have pandoms "to pay", pandoma "payment", borrowed from the Anglo-Saxons. Similar words are in the other Germanic languages. It is believed that they have been early borrowed from Latin where pondō "pound" and pondus "weight" are present (KLUGE FRIEDRICH. 1989: 542). However, the Mari word is closest to the Latin words and if no other explanation for its etymology will be found, its appearance can be connected with the time when the Italics were still living in Europe.

The formation of the numerals in different languages can also light some of the details of intertribal trade. For example, a common Indo-European protoform of the numeral for ten was restored as *deќm. It can be linked to the ancient Turkic *dekim "a lot", the warrant for its existence is the presence of O.T. tekim "a lot, many". During inter-tribal trade, Turkic word with a total value took at Indo-Europeans a more concrete meaning. Fin. *deksan "ten", present in words kahdeksan "eight" and yhdeksän "nine" can be associated with the Turkic numerals doksan / tuksan "ninety". For a time words like toquz and on / un were synonymous, meaning "ten", in the Turkic languages. Then the words doksan and tuksan can be explained as "ten of tens" that when trading by dozens of units of goods (such as skins) could be perceived by Finnish people simply as "ten" and the Turkic word was taken in the western Finnish languages just in this sense. More details about all of this in the section "To the primary formation of numerals in the Nostratic languages". The fact of trade by dozens can be confirmed by the replacement O.S. word četyredesętĭ in East-Slavic by the word sorok "forty" borrowed from the ancient Bulgars (Chuv. hĕrĕh "forty"). It is known that four dozen small articles were perceived as a distinct trade unit, namely by the Eastern Slavs as "a bunch of sable skins" (VASMER M. 1971: 722). This is the number of skins needed for the manufacture of sable fur.

This paper outlines and sketches a schematic picture of trade in Eastern Europe, mainly adjacent to the Northern Black Sea coast. However, no doubt that there were trade relations between the Baltic, Volga, and Ural regions. The Volga River and along the coast of the Caspian Sea should be the trade route in the direction of Central Asia. Linguistic data to review the topic are enough scanty as the ethnic composition of the population in these regions is not enough clear.

References

Davis J. 1992. Exchange. Buckingham: Open University Press.