The Names of Metals in the Turkic, Indo-European, and Finno-Ugric Languages

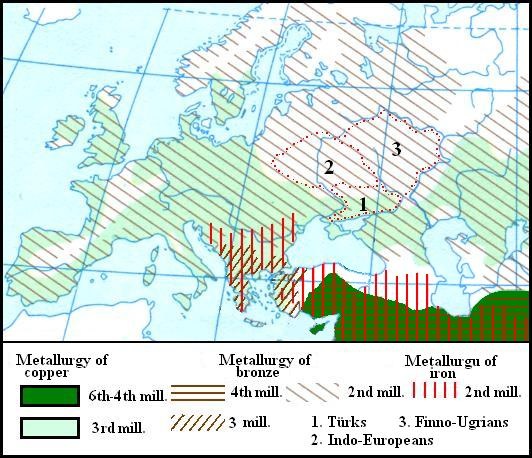

Indo-European, Turkic, and Finno-Ugric languages belong to the large macrofamily of Nostratic languages. They were formed in Transcaucasia and later migrated to Eastern Europe [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998]. Their migration and further dispersal are shown in Fig. 1. The proximity of the areas of speakers of Nostratic languages predetermined the routes of dissemination of cultural achievements, including metals and their names.

Fig 1. The Resettlement of the Indo-European, Turkic, and Finno-Ugric tribes in Eastern Europe.

Legend: Nostratic peoples: A-A – Abkhazo-Adyge, Dag – Dagestabians, Dr – Dravidians, Kar – Kartvelians, I-E – Indo-Europeans, NC – the speakers of North Caucasian language, S/H – Semits-Hamits, Trk – Türks, Ur – Uralians.

Indo-European peoples: Arm – Armenians, Balt – Balts, Gr – Greeks, Germ – Germanic, Illyrians, Ind – Indo-Aryans, Ir – Iranians, Ital – Italics, Celt – Celtic, Slav – Slavs, Toch – Tocharians, Thrac – Thracians, Phrig Phrygians.

Finno-Ugric peoples: Est – Estonians, Fin -Finns, Hung -Hungarians, Khant – Khanty, Lap – Sami, Mans – Mansi, Mord – Mordvinians, Udm – Udmurts.

Turkic peoples: Alt – South Altaians, Chuv – Chuvashes, Yak – Yakuts, Khak – Khahasians, Tat – Tatars, Trkm -Turkmens.

Common names of metals are absent in Indo-European languages. The Indo-European community was formed when people didn't know any metals. The Turkic languages have common names for almost all used metals, though Turks as ethnos were being formed simultaneously with Indo-Europeans. As it is shown by our studies, in the 4th – 3rd mill BC the Turks occupied the territory between the Dnieper and the Don Rivers to the south-east of the Indo-Europeans [Ibid: 42-53]. They were more closely related to metallurgical and metal-working centers of that time. Archaeological evidence suggests that the development of metallurgy in Eastern Europe began under the influence of the more advanced cultures in the Balkans:

The Copper Age was characterized by the forming of the Balkan-Carpathian Metallurgical Province. This system of related manufacturing hotbeds occupied mining and metallurgical centers of the Northern Balkans and the Carpathians, where extremely bright farming and cattle-breeding Eneolithic cultures of Gumelniţa–Karanovo, Vancea-Pločnik, Tisapolgar-Bodrogkerestur, Petreşti were located. The widely known Trypillian culture in the southwest of the USSR was only the eastern province of this block and did not know their industry: its masters used imported copper. Since the time of forming the province a large proportion of products from the Balkan and Carpathian centers was sent further to the east in the Eastern European Steppe and Forest-Steppe (CHERNYKH E.N., KUZMINYKH S.V. 1990: 136.)

Trypillian culture is closely connected with the culture of Cucuteni in Romania; therefore, they are collectively called Trypilla-Cucuteni culture. One can say that the origin of these cultures is in Asia Minor. It existed on the territory of Right-Bank Ukraine and Moldova in the VI-III millennium BC and left behind numerous archaeological sites. The creators of this culture came from Asia Minor and were Semites. They settled the territory south from the Indo-Europeans in the Southern Bug and Dniester river basins. The Trypillians were more engaged in farming than livestock-breeding and large and small horned cattle and pigs prevailed in their herd, but the horse, although it was known, was not very common [ZBENOVYCH V.G. 1989. 1989: 152; KUZMINA E.E. 1986: 181]. In Trypillian osteological collections, the horse is represented only by single specimens (BURDO N.B. POLISHCHUK. 2013: 71).

Like the Nostratic, other peoples also populated Europe moving from Western Asia through the Balkans. Their spread is associated with the emergence of metallurgy in Central Europe (see Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Dissemination of metallurgy in Europe in 6th-2nd mill. BC.

The map was compiled according to "Atlas for History" [BERTHOLD LOTHAR (Leiter). 1973, 5.I]. The map also shows the territory of the settlements of Nostratic peoples in Eastern Europe in the 5th-2nd mill. BC.

The Turks created the Seredniy Stiğ and Old Pit cultures. They mainly engaged in animal husbandry and horse breeding dominated in some communities. Thus, the economic structure and ethnicity of the population on both sides of the Dnieper were different but commercial and cultural exchange existed between Turks and Trypillians without of doubt.

Thanks to this exchange, the Turks became acquainted with metals through the Trypillians. At that time, words for the names of gold, silver, and copper were spread among them and became common. Acquainted with the metals through the Tripillian people, the Turks borrowed also their names from them. G. Ramstedt found it possible to associate the common Türkic altyn gold with Ar. lätün "brass", which name the Turks could transform for the convenience of pronunciation [RAMSTEDT G.J. 1957: 36], could sound similar in the Ttrypillian language. Transferring the names of some metals to others is a typical phenomenon. For example, the same altan means copper in the Yakut language, while gold is called a word, meaning silver in other Türkic languages. There are many similar examples, therefore, we will keep in mind this phenomenon in our research. While establishing the origin of the names of metals, it is also important to observe that they have long served as a commodities, just like livestock or artificial products.

The Turks borrowed from Trypillans also the name for the silver which they first call kümüĺ turned in kümüš later according to the law of Turkic phonology (see. Hypothetical Nostratic sound RZ: To the Problem of Rhotacism and Zetacism) The original form has been preserved in the Chuvash language as kǝmǝĺ because it is closer than others to the mother tongue of the Turks. While a great bulk of the Turks departed eastward in the 3rd mill. BC, even earlier their part crossed the Dnieper River and and lost contact with their relatives. The tracks of Trypillian influence can be found among the words having a sense of “commodity”, “goods”, and “payment”. Widely spread word tovar in different forms had many senses in Turkic, Indo-European, and Finno-Ugric languages – “salt”, “linen”, “ax”, “cattle”, “sheep”, “goods” etc. The correspondence to it exists in Hebrew – toar “product, ware”, davar “a word, a thing, something”. The Trypillians had to have also the word *kemel, corresponding Hebrew gemel “to pay”. Silver was used as money at that time and therefore Hebrew word changed its sense in the Proto-Turkic language after borrowing.

After the Turkic tribes crossed the Dnieper, the previous contact between them and the Indo-Europeans became closer. This fact is testified by numerous Chuvash-Indo-European lexical correspondences. One of the borrowings from the Turks was the name for silver, which was preserved in Latin. Ancient Italics used this word as the name of the silver dish or plate (Lat caměl-la “plate for liquids”).

Meanwhile, it is believed that the Turkic name for silver has Chinese origins [LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 1997: 142]; arguing about this is as useless as trying to prove that the ancestral home of the Turks was in Europe. Let's move on to the name of copper. The Turkic languages have two words for copper which are used differently for naming copper, brass, and bronze. The oldest of them is baqır, as indicated by the Chuvash păkhăr "copper". M. Räsänen derives this word from the Persian bahır [SEVORTIAN E.V. 1978: 46]. However, this word is not considered in the etymological dictionary of Iranian languages, that is, it is considered borrowed [RASTORGUYEVA V.S., EDELMAN D.I. 2003]. I think it can be associated with a hypothetical Tryp. *vakar “bull, ox” or “cow” [Ar. بقرة (bakara) "cow", Hebr. בָּקָר (bakar) “cattle”]. It is clear that copper, like cattle, was a commodity and the Turkic herders exchanged cattle for copper from the Trypillians. The origin of the second Turkic name for copper mis is unclear it appeared much later. A common word for tin needed for bronze production was absent in the Turkic languages and even closely related used different words for this metal. However, copper metallurgy was developed by the Turks under the influence of the Trypillians due to the presence of copper ore deposits in the Donbas. It is evidenced by archaeological founds of ancient mines within the Bakhmut tectonic zone. The chemical composition of metal products from Donbas suggests that the metal was obtained not from imported but from local ore [KLOCHKO V.I., MANICHEV V.I., BONDARENKO I.N., 2005: 111].

Already having some experience, the Turkic people continued metalworking craft based on imported metal from the Carpathian region and exported their metal products to northern neighbors. Thus some of the Indo-European ethnic groups obtained together with hardware also names of some metals from Turkic and sometimes used them for other metals. The Italics borrowed from Turks the name of copper and used it for the naming copper beaker (Lat. bacar “goblet”). Similar words are present in English and German, but they were borrowed from Latin. The name for the ore in the Germanic languages (OS aruz, OHG. aruz, etc.) is considered to be borrowed from Sumerian urudu "copper" by unknown way. The intermediaries were the Trypillians, there is arad "bronze" in Hebrew. Whether also Slavic names of the ore (ruda) can be concerned here, is not clear.

The Indo-Europeans borrowed from Turkic the name of sulfur which could be called by them according to its yellow color sarpur “yellow chalk” (Chuv. sară "yellow", pură "chalk", ă – a short vowel which could fall out at pronouncing). The Latin name of the sulfur sulpur is considered as “Wanderwort” of Mediterranean origin (WALDE ALOIS et al. 1965) but it originates from a Proto-Chuvash word. Similar names are presented in Germanic names of sulfur (Ger., Schwefel, Eng. swefl, Goth. swibl etc) which were developed from *sarpur. The Germanic words could be borrowed from some unknown language (KLUGE FRIEDRICH. 1989: 659). The origin of Slavic names of the sulfur (sera, sira, siara, etc.) is not clear. Probably, they have reduced forms from sară “yellow”.

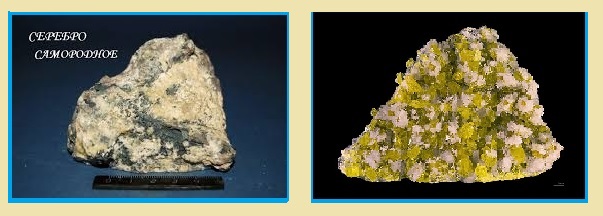

Fig. 3 Left: The native silver, right: crystals of the native sulfur.

The native sulfur has a pale color and is like silver in appearance (see Fig/ 2) therefore the name of sulfur has been transferred to silver in the languages of those Indo-Europans who populated the north-western part of the total territory of Indo-European (Germanic, Baltic, and Slavic tribes) and were not familiar with silver. The similarity of OE seolfor "silver" and Lat sulphur "sulfur" confirms this fact fairly well. However most of the Indo-Europeans had long been familiar and had their name for silver which originated from PIE ar(e)-g "glittering, white" (Lat. argentum a.o.). In other languages, the name of silver could be formed both by borrowing and by modifying own names of sulfur – Ukr. sriblo, Bulg. srebro, Pol. srebro, Laus. slobro, slabro, Ger. Silber, Eng. silver, Goth. silubr. Probably Alb. sёrma "silver" belongs here too. The Germanic and Slavic names of silver and sulfur are not considered related by specialists. The name of silver is said to be borrowed from some Middle Eastern language. For example, Assyrian sarpu “refined silver” from sarapu "to refine" is considered as a primary source. However, the Assyrian word stays further from the Indo-European names of silver and sulfur phonetically and semantically as originating *sarpur.

Let us consider the name for the iron. Turkic peoples use words jez, zez, čes (Chuv. yěs) calling copper or brass. It originated from the ancient form *jEř. The Nostratic fricative trill ř almost was not kept in the Turkic languages though it exists in Czech till now and existed in Polish (it was kept in spelling rz). In most cases, this consonant has been transformed to z in the Turkic languages. Anna Dybo thinks that the Proto-Turkic name of the copper was borrowed from the Tocharian (Toch. B yasa, Toch. A wäs "gold") (DYBO A.V. 2007: 125). But Latin words aes, aeris (obviously both originate from *ears) “copper, bronze”; "copper ore") indicate the existence of an ancient form jeř. This root can be referred to as a common Nostratic stock and it was used for the name of both gold and copper. Indo-Europeans were modified only for the name of the gold (Lat. aurum, Old Pr. ausis, Wel. awr). Since the Turkic people mastered the metallurgy and metalworking of bronze before the Indo-Europeans, the latter became bronze tools and weapons from them, and together with items borrowed the name of the metal used for the manufacture. Later this name was transferred to the name of the iron in some Indo-European languages. Germanic people (Lat. Germani) have added the attributive suffix -an to the root jerz and an Old-Germanic word got the form *jerz-an and later it has turned to isarn in North-Germanic, to eisarn in Gothic, to Eisen in German, to iron in English. The primary Turkic form for the name of copper is kept in the word zerz “rust” which exists in Lusatian (Sorbian) languages. This form was transformed in Slavic *zelz-o with the meaning “iron” (Ukr zalizo, Rus żelezo, Bulg, Pol żelazo, etc). On the other hand, the ancient Turkic word zerz in lightly altered form has been kept in Ukr. žers-t’ “tin-plate” (the similar Russian word žes-t’ has lost r). Baltic names of iron were borrowed from Slavic (Let. gelezis, Lit.dzèlzs). Some linguists connect also Greek calkos “copper, bronze” to the last words but this seems to be doubtful. Most likely, the Greek word ιοσ "rust" can correspond to the root jerz. The homonym of this word means "poison" and it gave grounds for A. Fick to consider their common but vague origin (FRISK H., 1970)

The name for the gold. In etymological dictionaries, the Indo-European names of the gold (Old-Slavic. *zolto, Germ. *gultha) are deduced from the root *ghel “yellow, green” (KLUGE FRIEDRICH. 1989: 271-272. VASMER M. 1964: 103-104). This is very doubtful as Indo-European front vowels e were not changed usually in labialized back vowels o or u. We shall consider the assumption, that Germans and Slavs have borrowed the name of gold from the Proto-Chuvashes. The Chuvash call gold yltan. Initial vowel y was difficult to pronounce therefore it became prothetic consonant gh, which is typical for the Indo-European languages. The new word ghyltan has received the form of an adjective and was used in such function (cf. jerz-an). Later the noun ghulta was formed from the adjective which has been developed to Old Eng gold, Goth gulth, Germ Gold. Slavic word for gold could not be borrowed directly from Proto-Chuvash as then it would have the form vylto as the prothetic v is typical in the Slavic languages. On the contrary, the transition gh to z is possible. The name of the gold has been borrowed from Germanics also by the Iranians, but they have transferred it to the name yellow color. The closest to the Germanic form was kept in the Ossetic language – zäläd. Other Iranian languages use the name of the yellow color the word zard. Most Iranians call gold zar though the other word tilo/telo also exists but its origin is not clear at present.

The name for the copper and brass. The German language has a word of not clear origin Messing "brass" (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 475). Similar words are presented in other German languages. Many Slavic languages have the word misa “a bowl”. One can relate it to the German word as there is a dialectic form midnycia “copper bowl” in Ukrainian (mid’ “copper”). Maybe, both Slavic and German words are borrowed from Iranian languages where words mes, mis "copper" are presented. Iranians borrowed this word from Finno-Ugrians which call different metal by such words: vask, vas, veš’, bes etc. The origin of these words can be connected with Sumerian guskin “gold”, also they must be primary. The word for the name of copper was borrowed from Iranians by Turkic, Slavic, and Germanic peoples. Maybe, the German word Messer “a knife” has the same origin.

Another name for copper. In Germanic languages, the name for copper (English copper, German Kupfer, etc.) is considered to be borrowed from Latin cuprum, which in turn is supposed to be borrowed from Gr κύπριον „aes cyprium", but a dubious possibility of borrowing from the ancient Hebrew k’pōr "lid" is mentioned (WALDE ALOIS et al. 1965: 214). Semantically and phonetically, this word is similar to the Turkic words meaning "bridge" (Chuv. kĕper, Kaz. köpir, Turkish köprü, etc.). Their origin is unclear and borrowing from Turkic into other languages, including Arabic, is assumed (LEVITSKAYA L.S. et al. 1997: 112-114). The connection between the meanings "to cover" and "copper" is explained by the fact that copper was sold in plates that could be used for coverings. Ar. كوبري (kubri) "bridge" may be genetically related to Old Hebrew k’pōr. Then it can be assumed that a similar Trypillian word was borrowed into the Turkic languages with the meaning of "cover" and then "bridge", and into Italian, and from there into Latin – with the meaning of "copper".

Explaining the Turkic name for the iron is difficult. Turkic peoples use the word demir/temir calling so iron and ironware. According to its meaning, this word had to appear later as the names of other metals. But a satisfactory etymology of the word demir doesn’t exist. The Hebrew language has the word demis “money”. The Trypillians could borrow and use it in the form *demirz in the same sense. The first things about iron were considered costly by people. Therefore, we can suppose that the borrowed from the Trypillans word meant just “a costly thing” for a long time but after the emergence of iron, this sense was transferred on the iron things. Attention is drawn to the similarity of the Türkic word demir/temir to gr. θέμερος "solid, strong, hard", without a reliable etymology. It can be assumed that the Türks had a broader meaning for this word, and the ancient Greeks borrowed it from the Türks in their ancestral home precisely in the meaning of "solid", which they developed in another direction.

It is also difficult to give an explication of the Turkic name of the lead. It has different but similar forms in individual languages. Some of these words can be near to the initial form – Kaz qorğasyn, Karach.-Balkar qorğašyn, Tat korgošun, Uzb korgašin, Kirg korgošun and other similar. Perhaps the word is compound and consists of two partial words kur/kor and gošyn/gašyn. Hebr kur “a forge, melting pot” suits well for the first part, therefore, the second partial word must have an appropriate sense. Nothing better as košer “applicability, suitability” was not found in Hebrew. Thus, the name of the lead can have the meaning “suitable for fusing”.

Finno-Ugric languages

Like the Indo-Europeans, the Finno-Ugrians did not know metalworking, but unlike them, the Finno-Ugric languages have one common word for the name of metal in general:

.

The oldest such name in the Uralic languages is PU *waSke (the root is present in almost all Uralic languages in the meanings of ‘copper’, ‘non-ferrous metal’, ‘metal in general’, ‘iron’, ‘metal decoration’, etc.) [NAPOLSKIKH V.V. 2015: 60]

.

The Finno-Ugric languages with Samoyed constitute one language family called Uralic, which is a historical misunderstanding. The modern speakers of these languages had common ancestors, whose original homeland was not somewhere in the Urals, but around Lake Urmia in north-western Iran in the highlands. Their southern neighbors were the ancient Dravidians, the language of which, together with the Uralians, was part of the Nostratic macrofamily, that is, it had some common features with Uralic especially since their habitats were neighboring. The likeness of Finno-Ugric and the Dravidian word for the number four (Fin. neljä, Erzia nile, Mansi nila, etc. – Malayalam nālu, Telugu naalugu, Tulu nāl etc) may be an example. Some parts of the Dravidians can be associated with the ancient Sumerians. In the 6th millennium BC, both the Urals and the Dravidians should be familiar with gold, whose nuggets could be found in the surrounding mountains. It was the first metal with which people were well acquainted. The Sumerians called gold guškiu the Uralians called it by the mentioned word which is considered to be borrowed from Tocharian (Ibid. After meeting with other metals, Uralians transferred this name to them: Saam. vešš'k, Est. vask, Fin. vaski "copper", Mord. us'ke "iron", Khant. wax "metal, iron, money", Nenets wies’s’ä "iron, money", Selkup kwǝs "metal" a.o. The common Uralic form of these words is restored as *was’k [ALATYREV V.I. 1988: 57]. The Indo-European and Turkic languages have no similar words of this root. How the common form was transformed and used for the names of different metals is shown on the example of the Udmurt and Hungarian languages.

Silver in the Udmurt language is called azves'. The first part of this word has no clear explanation [Ibid]. However, the word *aš existed in the Proto-Uralic language. Its meaning can be restored after Erz. ašo, Mari oš "white" and the words of the Baltic-Finnish languages used to denote a bird of white color. This Nostratic word is well preserved in the Turkic languages as aq "white" and less in Indo-European – Slav. jas-, Iran. ašk (Pers. ašekar a.o.) "clear". We see it in the name of silver in the Udmurt language, where the second part ves' means metal since it is also present in the name of the lead (uzves'). For the first part of the name of the lead, nothing suitable was found in the Udmurt language, except for the word vuz "commodity". However, the idiom "commodity-metal" suits better for silver, which has long been the subject of trade, that is money. One may think that originally the Udmurts called the silver both “white metal” and “trading metal” and after meeting with the silver-like lead, one of its names was transferred to it. Later the name of the lead was transferred to the name of the tin as tӧdy uzves', that is the "white lead", and the lead itself for clarity got attribute s'ӧd "black" in another name s'ӧd uzves'. Komi names ezys' "silver" and ozys' "tin" were borrowed from Udmurt. Among the specialists (V.I. Abayev, Nikolai Anderson, Yrjö Wichmann, V.I. Lytkin) the prevailing opinion of these words is Hung. ezüst "silver" were borrowed from Ossetian [ibid, 58]. However, the Ossetian ævzist "silver" is a Hungarian loan-word, whose original form was ezvest, and the first part of this word had the same origin as the Udmurt az-.

In Hungarian, the final consonant k of the Uralic *was'k was not lost, as in Udmurt, but turned into t, and the original form was transformed over time into ezüst. In the etymological dictionary of the Hungarian language, the origin of the final t is considered unclear, as well as the prefixes ez-, and the Finno-Ugric origin of the word ezüst is considered unlikely, although, nevertheless, its second part is associated with Hung. vas "iron". A Hungarian linguist notes the kinship of this word with other Uralic ones, but their initial form is seen as *βas'ke, although this is almost the same as *was'k [ZAICZ GÁBOR. 2006]. As in the Hungarian language, in Mari the last sound of *was'k turned into t and in this way, the resulting word vašt, like as in Hungarian, got the meaning "silver", but without the definition of "white". In modern Mari, it took the form of vaštyr.

None of the Finno-Ugric languages did't preserve the original name of gold and borrowed words are used to define it. Fin. kulta, Est., Veps. kuld are loan-word fron Sw. guld "gold". Most other Finno-Ugric languages have loan words from Iranian (Mok. syrne, Udm., Komi zarni, Mansi sorni, Khanty sarn’e, Hung. arany out of Iran *zaranya – all "gold").

The name copper in several Finno-Ugric languages is connected with Lat. argentum "silver": Mari. vürgine, Komi yrgön, Udm. yrgon, Mansi ärgin – all "copper". The Latin word goes back to PIE. ar(e)-ĝ- (arĝ-ö), r̥ĝi- meaning "glittering", "white", "fast", having equivalents in many languages, but in Iranian languages it is represented only by Av. ǝrǝzata- "silver" [POKORNY J. 1949-1959: 64-65, WALDE ALOIS et al. 1965: 59] so it is doubtful that the Finno-Ugrics borrowed the word from the Iranians. The borrowing occurred from the Italics when some of their group migrated from the ancestral homeland in Eastern Europe not to the west with their main mass but to the east. In the middle Volga basin, they came into contact with the Finno-Ugrians, who borrowed words of cultural semantics from them [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2024].

The names of silver have quite late and different origins in the Finno-Permian languages [NAPOLSKIKH V.V. 2015, 61]. It is believed that the origin of the Fin. hopea, Est. hōbe, Veps. hobed, Saam. suohpe (all "silver") is derived from the meaning "soft" or "flexible", but it is not indicated what language has such a word [HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007, 209-210]. However, the name of silver in these languages was borrowed from some Iranian having sense of "white". The most convincing evidence of this is the similarity of Veps. hobed to Afg. saped, Pers. sefid and Gil. sǝfid "white". The Veps were the closest neighbors of the Iranians in the ancestral home.

The Ossetians also borrowed the name steel from the Hungarians. It is called in Ossetian ændon. Other Iranian languages have no similar words, while they are quite common in the Finno-Ugric (Udm. andan, Komi emdon, Mansi ēmtan "steel"). In Hungarian, this word can be connected with the name cast iron öntottvas, where öntott "cast" and vas "iron". The English name for cast iron is formed using the same semantic structure. In favor of the proposed explanation is Hung. adz "to harden, temper", which also comes from önt with the addition of the suffix sz, which characterizes multiple actions [ZAICZ GÁBOR. 2006: 163]. However the name of the steel in the Finno-Ugrian languages has an unclear suffix on/an, but it can be preformative for nouns.

Thus, we can conclude that the names of steel, copper, and silver were not borrowed by the Finno-Ugric from the Ossetians, on the contrary, the Ossetians, familiarized themselves with the new metals through the Magyars, took over their names. About gold is difficult to say because its name is common in similar forms in the Iranian and Finno-Ugric languages, but, although it has Iranian origin, the way it spread is unclear.