Southwest Asia as a Neolithic Cultural Center

The impressive successes of paleogenetic research in recent decades have enriched our knowledge of human cultural evolution since ancient times. In this regard, the works devoted to human economic activity and especially the development and spread of agriculture (SHENNAN STEPHEN. 2018, KRAUSE JOHANNES mit TRAPPE THOMAS. 2019) deserve attention. Both works claim that the spread of agriculture to Europe came from the territory of modern Turkey, i.e., Anatolia. Agreeing with this rather widespread point of view, I would like to supplement the authors in some way. When we talk about cultural evolution, the fact that different peoples at different stages of history made different contributions to this process is of no small importance. More or less accurate knowledge about this is important from a political point of view, because it can help maintain peace and mutual understanding in the world. Existing erroneous theories have been and continue to be the basis of international conflicts that have led to military clashes. The emergence of erroneous theories is influenced by the patriotic sentiments of historians, who are searching for the greatness of their own people in the past. However, the Eurocentric convictions of historians are more harmful. Over time, such sentiments lose their sharpness, but they can be found in the above-mentioned works. Daniela Nofmann has reviewed these works from a professional point of view (HOFMANN DANIELA. 2019-1, 2019-2), but in them, one can find polite reproaches for the hidden Eurocentrism of the authors (HOFMANN DANIELA. 2019-2: 435). While agreeing with the authors that knowledge of the characteristic features of social and historical processes is necessary to understand the emergence and development of Neolithic populations, she believes that they did not sufficiently take into account other factors to understand the hidden causes of the transformation of society:

By putting these issues centre-stage, this book is important and timely. But if you also think that it is vital to know how social and historical processes impacted the people who experienced them, how daily existence changed, how decisions were reached and societies transformed, then this volume will leave you dissatisfied (DANIELA HOFMANN. 2019: 3).

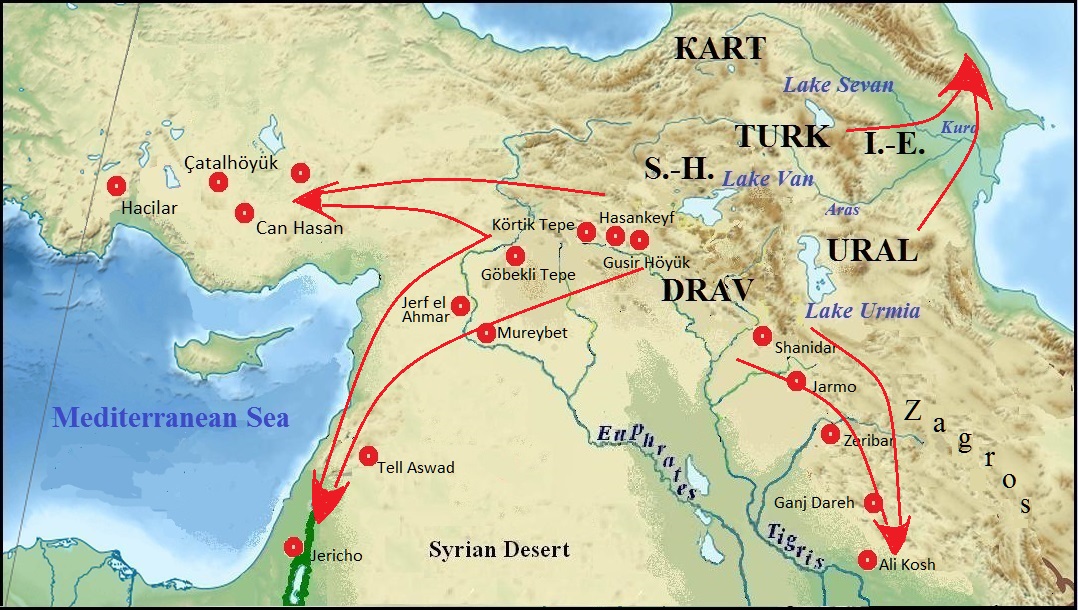

It is usually assumed that the cradle of human civilization was the so-called "Fertile Crescent". This territory is, indeed, a crescent on the fertile lands between the Mediterranean and the Iranian Plateau and is bounded on the south by the Arabian desert, and on the north ridge of Jabal Sinjar (see the map from Wikipedia at right). However, we can assume that it was the second stage in the development of human civilization. The cradle of human civilization could be regarded as just the three lakes region, where we have defined the Urheimat of the Nostratic people

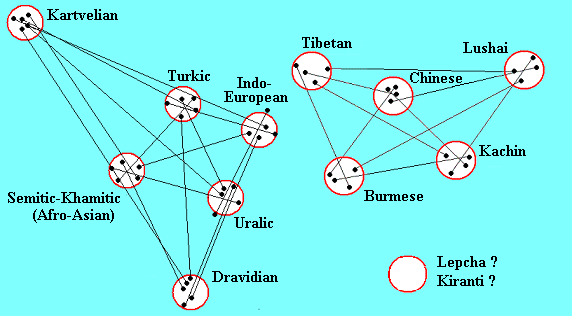

The Nostratic languages are mainly Indo-European, Turkic, Afro-Asiatic, Uralic, Dravidian, and Kartvelian. However, they may also include others, namely the North Caucasian languages such as Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestan. The study of the six languages using the graphoanalytical method made it possible to determine the location of their ancestral home in Western Asia in the region of three lakes: Sevan, Van, and Urmia (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 27-31). In the ethno-forming areas around these ozeps and the immediate vicinity, the formation of the proto-languages of these families took place (see the map below).

Habitats of speakers of Nostratic languages in the 7th millennium BC.

(STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 31, Fig. 8)

Designations:A-A – Afrasians, Dr – Proto-Dravidians, I-E – Proto-Indo-Europeans, Kart. – Proto-Kartvelians, Tur – Proto-Turks, Ur – Uralians

The formation of the Sino-Tibetan languages also took place in this place, as evidenced by the similarity of the graphic model of the relationship of these languages with the Nostratic model (see below).

|

The comparison of the kinship models of the Sino-Tibetan and Nostratic languages

The idea of the Urheimat of the Sino-Tibetan people in Western Asia is not new. French scholar Terrien de la Couperie (1845-1894), the author of the book "The Early History of Chinese Civilization," found a distinct resemblance between the Chinese and the early Akkadian hieroglyphics. This topic is discussed in more detail in the article The Formation of the Sino-Tibetan Languages and their Speakers Migration

The locality around three lakes was very comfortable for settlements because it had very favorable geographical and natural conditions for primitive life. The surrounding area consists of many mountain ranges and plateaus that are located between deep troughs. Finding refuge in the cold season, Paleolithic man mastered cave dwellings in the Caucasus much earlier than in the neighboring regions of the Middle East. The Caucasus is one of the first places (and possibly the first) by the number of sites of Stone man (LUBIN V.P. 1998: 49). The intense colonization of the Caucasus by the first man took place in the Acheulean times (Lower Palaeolithic era), although archaeological finds of earlier times are known too. By the end of the Acheulean period, people had already invaded the territory of modern Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the North Caucasus (sites in Azykh cave, Dmanisi, Kudaro, Muradovo, Tsona, Karakhach). S. Sardarian, describing the geographical conditions of the country, writes:

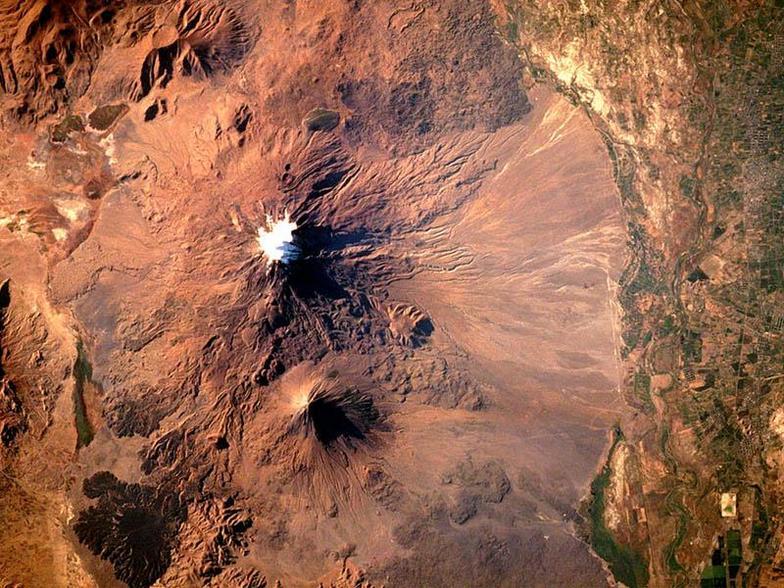

In ancient times, due to huge underground explosions, lava streams filled the abysses, leveled land contours, and simultaneously lifted them. Alluvial deposits also gave extraordinary fertility of the land (SARDARIAN S.A., 1954: 25).

There are many mountains of typical volcanic origin, the most known of which are the Ararat and Aragats. Mt Ararat is 5156 meters in height, broad, and fertile Ararat valley height of 800-1000 m above sea level, spread out around (photos left and below). The mountains have rather gentle, wooded slopes and deep rivers that originate outside the snow-covered peaks, nourishing the vegetation of the mountains and the surrounding plain. The locality, due to its wealth of obsidian deposits, convenience for hunting, and water supplies was during the entire Quaternary a very favorable habitat for Paleolithic man. Here is how Marco Polo described the area near Mount Ararat:

Below… the snow does melt, and runs down, producing such rich, abundant herbage that in summer cattle are sent to pasture from a long way about, and it never fails them. The melting snow also causes a great amount of mud on the mountain. (MARCO POLO. 1986: 42)

Three large local lakes, around which settled people are relatively small, for example, the deepest depth of Lake Urmia is only 15 m, and the deepest of the lakes, Sevan, has a depth of only 60 m. Consequently, the water in the lakes is well warmed up, which contributes to breeding fish and, consequently, the development of fisheries in the local population.

The first modern humans were the ancestors of what now constitutes the Asian-American race. The basis for this assumption is the results of the study of the genetic relationship of the Sino-Tibetan languages (see The relationship of the Sino-Tibetan languages). However, there is no other reliable evidence for this yet. We can only assume that these first settlers were displaced by people of the European race. However, the time of this event is difficult to determine. Certain information can be provided by the vocabulary of Indo-European languages of economic content, namely, fishing.

However, T. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov write nothing about fishing for Indo-Europeans, and no common Indo-European name of the fish exists. But the Indo-Europeans did not dwell near any lake, and fishing could engage only to a limited extent. In contrast to them, ancient Turks and Uralians populated the lake shores and lived by fishing. The Turkic and Finno-Ugric languages have common words for calling fish balyk and kala respectively. Perhaps the Indo-Europeans engaged more in hunting. T. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov assert: "Detected traces special hunting terminology suggests a developed hunting activity" (GAMKRELIDZE T., IVANOV, V.V., 1984, 697). A similar thought about the ancient Indo-Europeans was expressed by N. Andreyev:

A significant number of words belonging scope of hunting and gathering in PIE shows that these two occupations (along with cattle in its initial stages) were the main means of livelihood in the era of the formation of PIE. This situation allows us to date the mentioned epoch at the turn of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic (ANDREYEV N.D., 1986: 39).

There are only insufficient archaeological data to suppose the ethnicity and lifestyle of the population in the area of the three lakes at Paleolithic times, as collected here late Paleolithic finds "… did not exceed the frame of small collections" (RANOV V.A., 1978: 196). The dating of the existence PIE society is justified by N. Andreyev due to a lack of PIE language "words… which would have pointed on a stall or at least paddock cattle maintenance", but the time of formation of livestock breeding, according to him, is considered to be in Mesolithic (ibid). T. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov assert the opposite: "Indo-European language reflected a developed system of livestock with the availability of main animals" (GAMKRELIDZE T., IVANOV V.V., 1984: 868). This is an example of how an understanding of the same facts can be quite different. To set the time, when around three lakes lived the speakers of the Nostratic languages dwelt in the locality around three lakes, let us consider still other facts.

Archaeological evidence suggests that in the VIII-VII mill. BC Southwest Asia was inhabited by people with quite a high cultural level. Even then large settlements with a population of up to a thousand people emerged here. (HERRMANN JOACHIM, 1982: 41). There were in the Middle East wild species now cultivated plants – wheat, barley, and legumes. Here, approximately in IX thousand people began to engage in primitive agriculture and animal husbandry, domesticating the first dog. Archaeology confirms that new forms of management were applied in places located not far from the lakes Van and Urmia:

During the VIII mill. BC small farming and pastoral groups, which only occasionally ventured down to the plain, were settling in the Zagros, Sinjar, and Taurus Mountains (BROMLEY Yu.V., 1986: 274).

At left: Photo from the site "Iran. Zagros Mountains"

Speakers of the Nostratic languages, which had settled a large space in Europe and Asia, later had to stay in Asia Minor for most of the VI-V mill. BC. We can assume that the Semitic-Hamitic and Dravidian people who occupied the southern areas of the Nostratic space began as the first to leave their Urheimats, settling in the mentioned highlands. Cartvelians, Turkic people, and Indo-Europeans remained in their places. You can connect with the three options of the Chalcolithic Culture of the VI – V mill. BC, which was determined by a known scientist (BROMLEY Yu. V, 1986: 294):

- In Southeast Georgia and West Azerbaijan (assuming that it was Cartvelian);

- South-East Azerbaijan (Indo-European);

- In the Ararat Valley of Armenia (Turks).

Semitic-Hamitic, settling further to the south and southwest, reached Palestine and founded here the city of Jericho, Byblos, and Shechem, and others.

Ar right: Excavation of dwellings in Jericho.

This assumption seems to be contradicted by the fact that "… there are in the supposed habitat of PIE speakers in VI – V millennium BC no archeological culture that would explicitly relate to the Proto-Indo-European one" (GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V., 1984: 891).

According to M. Andronov, relocation of Dravidians to South India was held at the II-I millennium BC, earlier in the III millennium BC Dravidian community existed somewhere in Pakistan (ANDRONOV M.S., 1982: 178). Dravidians can be associated with the site Yahya Tepe in South-eastern Iran, dating back to the V millennium, till the end of the II millennium. BC, and later cultures of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in India. In addition, we have to consider that the "Proto-Dravidian community was split by the end of the IV millennium BC when Dravidian-speaking tribes began moving in the south and south-east" (BONGRAD-LEVIN G.M., 1981: 301). Thus, at least for some time, but not later than the third millennium BC Proto-Dravidians inhabited the territory of Iran and Pakistan. Then they were absent in Asia Minor in the 5th millennium BC.

These and other evidence suggest that the existence of the Proto-Nostratic language should be assumed long before the VII millennium BC Start time and place of its formation are still difficult to determine exactly. However, V. Alekseev admits the possibility of the existence of centers, within which there were main events of race-genetic processes. One of such two possible sites in the world, he thinks to be in West Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean (ALEKSEEV V.P., 1991: 49). However, in 1947, the monocentric hypothesis was proposed by J. Roginskiy, supported by other researchers (CHEBOKSAROV N.N., CHEBOKSAROVA I.A., 1985: 151). Following this hypothesis, the type of modern man emerged in the Near East and the Mediterranean as a result of the mixing of different representatives of the Neanderthal type. There are reasons to believe that the "typological heterogeneity of Paleolithic humanity was smaller than that of modern one, and this is a clear argument in favor of the hypothesis of monocentrism. (SHCHOKIN HEORHIY. 2002: 77).

Speakers of the common Nostratic language undoubtedly stood still at a relatively low cultural level. Modern languages of this language superfamily have only vague traces of common forms in the accounting system (see " To the Primary Formation of Numerals in the Nostratic Languages"). Common numerals appeared in separate Nostratic languages after the split of the Nostratic community, although it is possible to find traces of subsequent borrowings. Also, there are no common words related to developed forms of economics and construction. There are among the 34 common language features found in materials of V. Illich–Svitych prevailing morphemes, pronouns, and verbs meaning "to beat", "to split", "to cut", "to chop", "to drill", "to bend", "to seize", "to tear", "to knit" "to scream". Words meaning "ear", "many", "deep", "night", "edge", and similar others are present too. Noteworthy is the fact that words from technological and hunting semantics dominated in this group, but there are two words for signaling very necessary during hunting. As an example is given separately a small list of the common lexical heritage of Nostratic languages, where maybe present words appeared in the period of the Nostratic community, as well as since later times.

Staying near their Urheimat in Asia Minor, the speakers of individual Nostratic languages fell under mutual influences in the economic and cultural life. The most successful technical solutions, as well as attractive cultural ideas, spread rapidly not only among neighbors but could cover more space. Borrowing objects and concepts was accompanied by the spread of their names. Of course, the more linguistic features had residents of neighboring areas, but it is also possible that the presence of such a community may indicate a common origin of languages whose speakers now reside at a great distance. In our case, there are certain correspondences between Finno-Ugric and Sumerian languages. Evidence of this can be found in the works of different scientists

T. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov asserted that IE *reudh "red (metal)" may be borrowed from the Sumerian language, which has the word urudu "copper" and Sum. guškiu "gold" associated with Indo-European names of the metal (the closest form of Arm. oski) and based on these two facts, find it possible to speak about the contacts between these languages and the proximity of their habitat dissemination. In connection with this, we may add that the Sumerian guškiu is very similar to the Finno-Ugric names of different metals, Lapp. vešš'k "copper", Est. vask "copper", Fin. vaski "iron" Mokhsa us'ke "iron" and others. Sumerian, belonging to a particular language family, has not yet been determined. If you try to search Sumerian-Ural parallels, you can find the following: Sum. urudu – Komi görd, Udm. gord, Hanty wêrte, Hung. vörös (from vöröz ← vöröt), all – "red" ; Sum. gir "oven" – Hanty kör, Mansi kur, Komi gor, Udm. kur, Est. keris "oven"; Sum. kaš "urine" – common Finnisf-Ugric *kusi "urine" (Finnish, Est. kusi, Veps. kuzi, Udm. kyz' ); Sum. kišib "an ant" – Fin. kusianen, Est. kusikas, Udm. kuz'yli "an ant"; Sum. kur "mountain" – Lapp. kurro, Mari kuryk "mountain" , Komi kyr "steep" , Mansi karys "high"; Sum. gal' "earth, place", Hung. hely – "place", Veps. kal'l' "a rock", Komi gala "limit" ; Sum. můd "blood" – Fin. mäta, Est. mada "pus" ; Sum. sub "to suck", "to breastfeed" – Hung. szopik, Udm. s'ups'kany, Mari šupalaš "to suck".

A List of numerous Sumerian-Finno-Ugric lexical matches is given on Body Parts. Some of them can be attributed to the common Nostratic heritage, and perhaps this is why some Hungarian scientists limit relatives of Sumerian and Finno-Ugric languages only in favor of the Hungarian language. One of them is Prof. Alfrėd Tóth, who concluded in one of his works that the Hungarian language does not belong to the Finno-Ugric family of languages and is a direct descendant of the Sumerian (TÓTH ALFRĖD, 2007). Here is not the place to evaluate the work of the professor; we only need to note that he focuses solely on the Sumerian-Hungarian lexical parallels, oblivious to their presence in other Finno-Ugric languages. Taking into account that no other languages of the Nostratic superfamily have similar ties to Sumerian, and that it does not belong to the Afro-Asiatic languages, we can assume that this language belongs to the Ural or Dravidian family. These languages were formed in neighboring areas, and their neighborhood should be reflected in the languages. The most expressive is the similarity of the Finno-Ugric and Dravidian words for the number 4: Finnish neljä, Erzya nile, Mansi nila, etc. – Malayalam nālu, Telugu naalugu, Tulu nāl, etc. The probability of a random coincidence of such similarity is negligible, and no other explanation has been found.

Possible belonging of the Sumerian (and Elamite) language to the Dravidian language family is explained because Proto-Dravidians populated the area closest to Mesopotamia (unfortunately, the Dravidian–Sumerian language connection in these studies was not studied specifically). A. Maloletko found Asiatic elements in the language and onomastics of Vasyugan Khanty. He cites two dozen examples of Khanty words in one of his works that have matches in the languages of Asia Minor and the Caucasus. An unexplained element lat is present among hydronyms prevalent in the basin of the Vasyugan River, which has matches in the region of Lake Van and the headwaters of the Tigris River (MALOLETKO A.M., 1990, 81-82).

You can also find parallels between Sumerian and Finno-Ugric mythology. For example, Mansi Kors-Torum, Khanty Num Kurys – the ancestor of the gods and the creator of the world (after the flood, the role of the supreme deity passed to his son Numi Torum) recalls the name of the Sumerian god-warrior Ningirsu (Nin-Girsu). Komi god-demiurge Yen together with enezh "heaven", Udm. Inmar "god", in(m) "heaven", Mari yimy "god" correspond exactly to Sum An – "heaven god" (AFANASIYEVA V.K., 1991. MFW. Volume 1: 75).

Another word was present in the Sumerian language for deity – dingir or diĝir, which connection with Turkic tengri, tejri, tanri, tärä "god" is considered undoubted. Fin. tunturi "high forestless mountain" иand Lapp. tundar, tuoddar "a mountain". They also include here Hatt. tux "deity", Circassian tkhe "god, deity", Indo-European *deiuos "god", "heaven" (KADYRDZIEV K.S., 1983, 130-148), and it looks doubtful for phonetic reasons. In contrast, Old Germanic match *đunra "thunder", "god of thunder" can hardly be a coincidence, but its origin has another explanation.

A theme of the flood is spread in different versions among the peoples of all continents (FRAZER J.G., 1986, 96-147). The most known is the Great Flood described in Genesis of the Old Testament. The legends narrate almost always that a righteous escape on an island, a tree, or on any floating craft. The widespread of this legend can not be random and should be based on a real event, so there were numerous hypotheses about the cause of the flood. At the beginning of the millennium, has become popular hypothesis emerged about the flooding of low-lying areas around the Black Sea due to the transgression of rising levels, caused by the break of the wall separating the sea from the waters of the oceans in the place of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles. The rise of global sea level began at the end of the last ice age as a result of the melting of glaciers, which concentrated large masses of water that flowed to fill into the ocean, raising its level considerably above the Black Sea. Detailed and interesting evidence of this is given by W. Pitman and W. Ryan (PITMAN WALTER, RYAN WILLIAM. 1999).

However, the water can not flood the Armenian plateau during that flood. Another cause exists acknowledged by the authors and advocates of the Black Sea deluge theory. They believe that the Bible legend was caused by flooding of the Persian Gulf due to the same rise of the ocean level:

Flooding was not catastrophic, but very great: the length of the Persian Gulf is about 1000 km. In addition, the Biblical evidence that "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth, and the windows of the heavens were opened. The rain fell on the earth forty days and forty nights" looks more like tropical monsoon rain in the Indian Ocean than the flood in temperate climates of the Northern Black Sea Coast. (ZALIZNIAK L.L. 2005, 8).

In any case, the flood could not happen just around Mount Ararat, although its name is somewhat similar to Turk. aral "an island". Using Old Turkic art "Plateau Mountain" (NADELIAYEV V.M. a. o., 1999) Ararat has been determined very accurately – "an island mountain". However, the Bible does not speak of Mount Ararat, but about the "mountains of Ararat", so we can conclude that Noah's ark landed not optional on Mount Ararat and it received its name later as a memory of the flood when people settled near it.

The existence of three large lakes near Mount Ararat fit very well with their three Noah's sons. Perhaps, the tradition preserved the memory of the three ancestors of the tribes, who settled around these lakes. A legend of Adam, too, can have a real basis. The word Adam meaning "a man" is present in almost all Turkic languages and also in Iranian, Caucasian, and Finno-Ugric. All researchers believed that it is of Persian-Arabic origin, but the Chuvash word etem has a form that can not be explained by borrowing. Mari aydems "a man" also can not be explained by borrowing, in contrast to the Udm. adyami "the same". The Khanty language has the word átamá meaning "people", as in form and in meaning it does not seem to be borrowed from Turkic. Chuvash has other words of this root: Atam – the name of a deity, a few unexplained geographical names – village Chavash-Etem, Tutar-Atem, the Etem-Shive River. The Chuvash expression "Etem yurtna shaman" (a small bone to bewitch), according to V. Sergeyev, reminds Biblical themes, he explains it as "a bone has loved by Adam" (SERGEYEV V.I., 1981: 105). Ossetian adäm means "people". Words of this root and similar sense ("a man", "a husband") are spread throughout the Caucasus: Georg. adamiani, Lak. adamina, Avar. adan, Agul. idemi, Ahv. ande, Bats. admiā, Buduh. idmi, Darg. adam, Lezgi itim, Rutul edemi, Chechn. adam, etc. Perhaps some of them are borrowed from the Arabic or Turkic languages, however not all. It is evidenced by the variety of forms. Presumably Germanic words meaning "a son-in-law" Ger Eidam, OE. ethum, Old Frisian athom could be originated from this root. Hence, there is reason to believe that adam is an ancient Nostratic word meaning "a man". It is believed that on – Heb. adamah has the original meaning "earth", "red". Such a prosaic explanation for the name of a person is somewhat doubtful. A man in the imagination of primitive people could differ from an animal that has a soul. In this regard, the word adam in the sense of "a man" can also be compared with Ger. Atem "breath, spirit" and other Germanic words of this roots and the same meaning. F. Kluge (A. KLUGE FRIEDRICH, 1989) compares Germanic words with Old Ind atma "breath, soul" ("Hauch, Seele"). J. Pokorny (A. POKORNY J., 1949-1959) relates Germ Atem to PIE *etmen "breath" and gives matches to it in the Indian and Celtic languages. G. Frisk (A. FRISK H., 1970) classifies here Gr ατμοσ " steam". Iranian words dam "breath" belong to this group. Consequently, the definition of man as a creature that has a soul is more believable than its origin linked to the earth. Such an explanation might be proposed later by scholars of the Bible.

If we assume that the speakers of the Nostratic languages left the primary habitats at the beginning of the 6th millennium BC. Some of them migrated to Eastern Europe at the end of the 6th – at the beginning of the 5th millennium BC, then one can understand the appearance of the Neolithic on this territory. Archaeological facts prove that Mesolithic settlements existed here next to the Neolithic settlements for a long time, that is, there were no incentive natural conditions for changing the management of the economy here. Here is what K.F.Meynander wrote about this:

The people of the comb-pottery cultures adopted from the simultaneous Neolithic cultures, among other things, the ability to make pottery, but they did not abandon the methods of farming that were characteristic of the Mesolithic era.(MEYNANDER K.F. 1974: 24).

The fact that fishing can provide a sufficiently reliable basis for the well-being of society has been noted by other scientists (FORMOZOV A.A. 1977: 20; SAHRHAGE DIETRICH, LUNDBECK JOHANES, 1992: 14).As you can see, even an example did not persuade people to change the conduct of their economy; they only borrowed what they needed. Thus, there is reason to believe that, along with the Neolithic economy, the Turks, Indo-Europeans, and Urals brought pottery to the territory of Eastern Europe. (The emergence of pottery is considered the conditional boundary between the Late Mesolithic and Neolithic complexes). There are few words of pottery technology in Indo-European languages. T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov believe that pottery emerged at the early stage of the Neolithic revolution and after the 7th-6th millennia BC. spreads from Western Asia to the territory of Europe )GAMKRELIDZE N.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984: 705). The first pottery that appears in settlements along the banks of the Dniester and the Southern Bug is similar to the dishes found in the Balkans, in Asia Minor (PELESHCHISHYN M., PIDKOVA I. 1995. 16). On the possibility of the Indo-Europeans settling in Western Anatolia, Northern Mesopotamia, and Transcaucasia in the 7th-6th millennia BC, according to H. Birnbaum (BIRNBAUM H. 1993: 13), said Renfrew (Renfrew C. Archeology and language: The puzzle of Indo-Europian origins. L. 1987). In this case, the Indo-Europeans, staying in the 7th–6th millennium BC in Western Asia and having mastered pottery, could have brought it to Eastern Europe.

All the facts presented here confirm the assumption about the formation of Nostratic languages in the area of the three lakes, but there are facts that contradict this assumption. One of them is that agriculture in these places appears later than in the Fertile Crescent, where it appears in the 6th millennium BC (see the map below). Other authors also testify to this when they write about the ancestral homeland of the Indo-Europeans, which they place in the same place where we placed the ancestral homeland of the Nostratic languages.(KRAUSE JOHANNES mit TRAPPE THOMAS. 2020, 139)

The spread of agriculture in Western Eurasia

The Linearbandkeramik is shown in green (image by D. GRONEN- BORN / B. HOREJS / M. BöRNER / M. OBER 2019 [RGZM/OREA], Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License) [HOFMANN DANIELA, PEETERS HANS and MEYER ANN-KATRIN. 2022: 287, Fig 3]

The arrow on the map shows that the practice of agriculture came to the Three Lakes region from Mesopotamia, but this does not mean that it was brought by newcomers from there in the 7th millennium, as shown on the map. Agriculture in Mesopotamia was developed by Afro-Asian tribes who migrated there from their area on the shores of Lake Sevan. At that time, the Kartvelians, Turkic tribes, Indo-Europeans, and Finno-Ugrians remained in their former places until the 6th millennium BC, and they mastered agriculture as a consequence of cultural contacts with Mesopotamia. Only after that did they migrate to Eastern Europe. However, not all Indo-Europeans left the Urheimat. Some of them, like the Kartvelians, remained in Asia Minor. These were the Hittites, whose language is Indo-European, but it developed in isolation from the others:

… Hittite root-words have in most non-Indo-European origin, only ten percent of them originated from PIE, while the forms of declension and conjugation, as well as forming new word, are distinctly Indo-European, although there are also representatives and morphological forms of Asia Minor (Asiatic) (KAPANTSYAN Gr., 1956, 79).

The Turkic tribe, following in the footsteps of the Indo-Europeans, settled the territory between the Lower Dnieper and the Don, where they became the creators of the Serediy Stih culture, which became the basis for the Yamnaya. Some of them moved to the right bank of the Dnieper and assimilated the creators of the Trypillian culture (5500-3000), who dwelled there. The Turkic people, as pastoralists, were not as numerous as the Trypillian farmers. However, having the best organizational experience, they acted as an ethnic class and a specific xenocratic (from the Gr. ξένος “stranger”, “guest”, “master” and κράτος “strength”, “power”) political system. Namely, they were who spread the various variants of the Corded Ware cultures across a wide area of Europe and simultaneously brought the genes of the steppe's inhabitants to Central Europe (more details see Turkic People as Carriers of the Corded Ware Cultures). Paleogeneticists have repeatedly written that the newcomers from the steppes brought their genes to Central Europe, but they mistakenly call them Indo-Europeans (KRAUSE JOHANNES mit TRAPPE THOMAS. 2020). This widespread misunderstanding provides grounds for adjusting the above map of the spread of agriculture to Central Europe (see map below).

The spread of agriculture to Western Europe and the expansion of the Turkic people.

On the map, the routes and spread of agricultural cultures in the 9th-6th millennia BC are shown in blue. The migration routes of the Turkic people during the spread of the Corded Ware cultures in the 3rd millennium BC and a small part of the settlements founded by them, which still exist, are shown in red. The purple arrow shows the cultural influence of Mesopotamia on the speakers of the Nostratic languages, who remained in the same places of settlement until the 7th millennium BC. The solid blue lines show the approximate boundaries of the spread of TK and LBK in different periods of their existence. Legend: Aa is the ancestral home of the Afroasiatic languages, TP is the ancestral home of the Turkic language, TK is the Tipilla-Cucuteni culture, LBK is the Linear-Band Pottery. The red dots indicate the border of the territory inhabited by the Turkic tribes from the 6th to the 3rd millennia BC. The LBK space corresponds to the early stage of culture (HOFMANN DANIELA. 2020: 152).

The first Neolithic culture in Western and Central Europe, which was brought through the Balkans by migrants from Anatolia, existed approximately in 5500-4900 BC (Ibid: 151). There is no direct data on the ethnicity of its creators, but it can be assumed that they were Semitic tribes, as were the creators of the Trypillian culture, who also arrived from Anatolia (see An Unknown Semitic Tribe in Ancient Europe History). Their descendants must have survived until the time when the Turkic tribes began to arrive in Central Europe. The study of the coexistence of cultures must take into account the ethnicity of their creators. "Steppe aliens" outnumbered the local population (KRAUSE JOHANNES mit TRAPPE THOMAS. 2020: 129). A significant shift in the Y chromosomes in the part of the genome that is passed from father to son explains this advantage well:

Men from the steppes, having come to Central Europe, fathered many children with local women. Genetic analysis shows that 80 percent of the migrants from the steppes were men (Ibid: 130).

Numerous ancient Turkic place names, deciphered using the Turkic language and preserved to this day, indicate that the Turkic people predominated in the population of Europe during the Bronze Age (see Correlation of CWC Sites and Turkic Place-Names). Then the question arises when and why they disappeared, and toponymy cannot provide an answer to it. Archaeological finds indicate that there was hostility between the Turkic people and the local population, which led to violence and revenge. The difference in housekeeping between the autochthonous and alien populations was small, both were farmers. The main difference was in the details of livestock farming. If the local population had one or two cows per family, the steppe aliens owned entire herds of cattle. Although the cows of those times gave several times less milk than modern ones, the milk diet contributed to an increase in the number of children in Turkic families. In addition, they improved the technology of grain growing, which also contributed to population growth. As a result, it turned out that, the Y chromosome brought by the Turkic people dominates in Europe [KRAUSE JOHANNES mit TRAPPE THOMAS. 2020: 131]. [Ibid: 132-136].

Most of the Turkic people who migrated from the steppes were men who married local women and had many children. The children were raised by their mothers in their language, so they learned their mothers' language better than their fathers. The same story happened in Bulgaria in the first millennium AD. The mothers' language became the native language of the children, although the name of the people is of Turkic origin.

Future comprehensive studies of material culture from a gender point of view can respond to the characteristics of social processes if they more accurately determine the sex and age structure of the population of the European continent in the Bronze Age, similar made by Daniala Hofman for the Neolithicum and draw such a conclusion:

In spite of these obvious differences in material, size and location, it is argued that anthropomorphs act as ambiguous forces in Neolithic societies while they can sometimes be read as reinforcing existing power relationships, the ways they are used and treated in practice also challenge existing structures (HOFMANN DANIELA. 2020: 150).

Acknowledgments: My thanks to Stephan Niemeier (Frankfurt am Main) for consultation and material support for the research.