The Expansion of the Finno-Ugric Peoples

The ancestors of the Finno-Ugric peoples, coming from the Caucasus, were settled over a wide area of Eastern Europe, where in ethno-producing areas between the Volga and Don Rivers where were arisen primary dialects from which later developed the modern Finno-Ugric languages (see the section The Finno-Ugric and Samoyed Tribes).

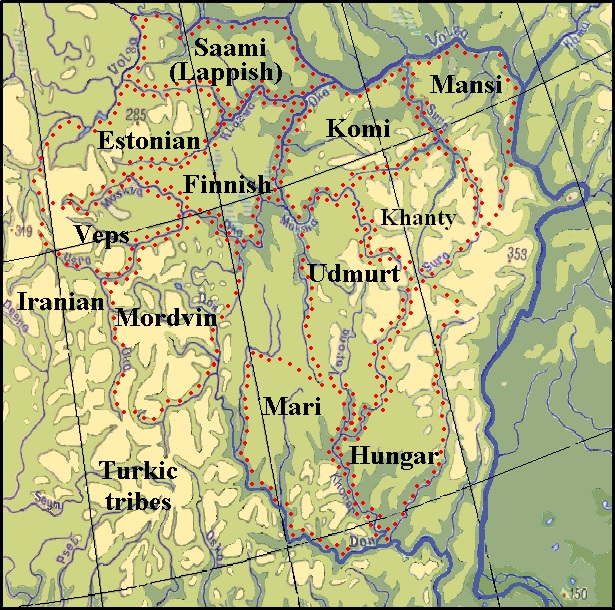

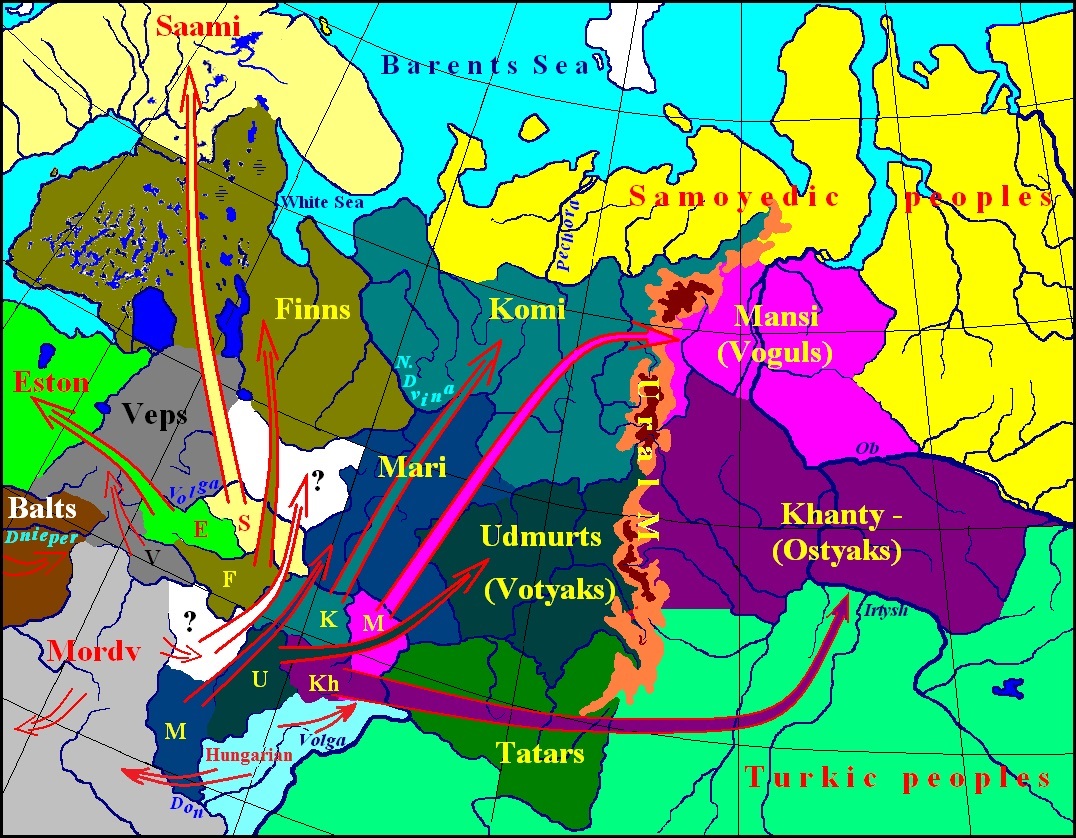

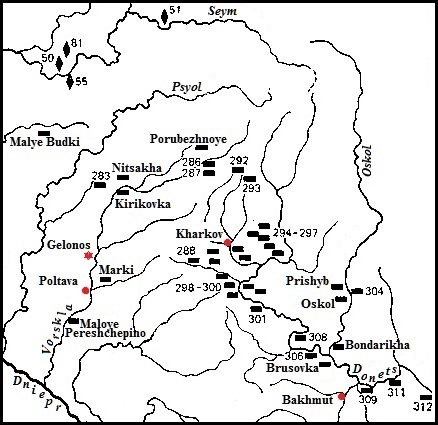

At left: The map of Finno-Ugric habitats in Central Russia

When comparing the location of the primordial areas of individual Proto-Finnish ethnic groups with the places of settlement of their descendants, it is clearly seen that the expansion of the Finno-Ugric peoples was directed mainly to the north and north-east and covered a very wide area. In general, the Finno-Ugrians migrated to the territory of those speakers of the Uralic languages, who began to settle beyond the Volga since the Neolithic times. Here a group of Samoyedic languages was formed on the space in which boundaries cannot be determined because of insufficient data.

Harsh natural conditions prevented the rapid population growth of this large area, so for a long time large uninhabited tracts remained here and attracted new settlers. At the same time, the remoteness of the Finno-Ugric settlements from the centers of agrarian civilization and the natural conditions didn’t conduce to borrowing useful crops and technologies, and to developing agriculture in general. Fishing and hunting dominated by an economy and such a way of economic development require large territories.

Studying ethnic processes in antiquity, V.Gening, referring to V.O. Dolgih's data asserted that 36 thousand Tungus hunters migrated throughout huge spaces of Eastern Siberia in the 18th century but at the same time the horse breeder and cattlemen Yakuts in a number of 28 thousand occupied the 20-30 times smaller territory in the relic Forest-steppe zone (GENING V.F., 1982: 103). The number of the inhabitants of some area is limited by the volume of subsistence can be delivered by it. Hunting and fishing are the basis of production even for small clans that required large spaces. Therefore, if favorable conditions promoted the growth of the population in some habitats, the relative overpopulation was arising, and the way out of this situation was the transition of a part of this excess population to new places (BRIUSOV A.Ya., 1952: 10). Having studied the life of the Northern-American Indians, L.Morgan describes the process of their settling insomuch:

The method was simple. In the first place, there would occur a gradual outflow of people from some overstocked geographical center, which possessed superior advantages in the means of subsistence. Continued from year to year, a considerable population would thus be developed at a distance from the original seat of the tribe. In course of time, the emigrants would become distinct in interests, strangers in feeling, and last of all, divergent in speech. Separation and independence would follow, although their territories were contiguous. A new tribe was thus created (MORGAN LEWIS H., 2000: 104).

Such a process of settling is named segmentation. And, as Bryusov believed, quite often it covered a large space, and migrants kept away often at a significant distance from the primary place of their settlements. Waterways that defined directions of population shifts were usually used (BRIUSOV A.Ya. 1952, 10).

The resettlement of the Finno-Ugric peoples began when their languages had already developed distinctive features due to staying for a long time each in its ethno-producing area. It started under the pressure of the Turkic tribes which migrated from their ancestral home in different directions since the beginning of the III mill. BC. (see the map at right). The migration of Turkic and Finno-Ugric peoples is well connected chronologically:

Tribes of typical the Pit–Comb Ware which appear in Eastern Baltic during the second half of the III mill. BC are regarded in modern archaeological literature as the earliest ancestors of the Baltic Finns (DENISOVA R.Ya. 1974: 29)

Sure enough, it can be assumed that the Turkic people as Carriers of the Corded Ware Cultures laid the foundations of their Fatyanovo variant and forced the Finnish tribes to migrate from the extreme western and northwestern areas. The places of settlements and migration routes of the ancient Turks are reflected in the toponymy, deciphered with the help of the Chuvash language, which has preserved individual features of the Turkic proto-language more than other Turkic languages. Having advanced along the Desna River to the Upper Volga basin, they occupied the land of Vepsians and Estonians. Ascertainment of the migration paths of individual Finno-Ugric peoples is helped by studying left by them place names of oldest times.

As the place names show, the Vepsians, the most western Finnish ethnos not immediately moved to their present places of residence, but settled in the neighboring lands close to their ancestral homeland. Moving westward was prevented for the Vepsians by Baltic tribes, which have expanded their territory to the east, and the Estonians, who immediately began to move to the Baltic Sea, prevented them to move north. Eventually, Vepsians moved after Finns and now inhabit the area east and south of the Estonians and Finns.

Further movement of the Turkic peoples along the Volga and Klyazma Rivers forced to migration also the Lapps (Sami), which occupied the northernmost area on the primary Finno-Ugric territory. They moved ahead of all in a northerly direction and eventually occupied the northernmost region of Europe in Scandinavia and on the Kola Peninsula. It must have happened about 700 BC, which follows from the arguments of Hans Fromm (FROMM HANS, 1990, 16). Overcoming this lasted at least several centuries.

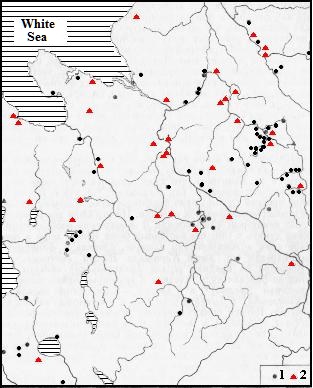

At left: The Baltic-Finnish and Sami toponymy of North Russia on the map of A.K. Matveev (MATVEYEV A.K. 1969: 46.)

1 – the Baltic-Finnic names; 2 – Sami names.

In accordance with the location of their historical ancestral home, the Finns had to move behind the Lapps and thus had to be east of the Estonians, which is just why their way lay towards the White Sea. Mapping showed that the Baltic Finns and Lapps occupied the north-western half of the Russian North (see the map above). The Baltic-Finns are considered to be the Finnish-Suomi and the northern Karelians. In the future, the Finns followed the Lapps along the western shores of the White Sea to the places of their present habitat.

The Proto-Khanty (Ostyaks) and Proto-Mansi (Voguls) occupied the extreme east of Finno-Ugric territory. Therefore they have begun movement eastward as the first. Proto-Mansi having been their habitat north of the area of Proto-Khantys, moved to their modern residence in a northern way. There are data about 1096 in the Old Russian Chronicle that some Ugric clan was being settled in the region of the river Pechora. This clan or tribe may be considered as the Mansi. Max Vasmer writes the traces of the ancient Mansi are available at the Upper Pechora and the Izhma river still 1396 (VASMER MAX., 1964-1974, V.1: 330). In addition, there are in Udmurtia villages of Igra, Upper Igra, Old Igra. The word igra is like the chronicle name of Mansi yugra, which has matches in Udmurt and Komi. Another indication of Mansi stay in the north of the European part of Russia may be Mans. vaps "son-in-law". If the Mansi and Veps were neighbors sometimes, a Veps could be a son-in-law of Mansi. Therefore, we can assume that the Voguls (Mansi) came to the upper Ob river recently bypassing the Ural Mountains in the most accessible place. The Komi tribes moved after the Voguls, the Votyaks followed them. Without a doubt, the migration of the eastern group of the Finno-Ugric peoples should be associated with the spread of the Abashevo culture across the Volga from the basin of the Sura and Sviyaga rivers. Because this culture existed in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, the beginning of the expansion of the Finno-Ugric peoples to the north-east and east should be referred at this time.

The hypothetical picture of the migration of Finno-Ugric tribes

Sketched here outline can be added by other logical considerations. The movement of Mordvinic tribes can be restored according to the separation of the first single language into two dialects, currently considered to be separate languages. Obviously, the ancestors of the Moksha- Mirdvins stayed in place for some time and only later moved west and south-west into the Seim and Donets Donets river basins, which presumably can be attributed no later than the beginning of the first millennium BC. On the contrary, the ancestors of the Mordvian-Erzya moved east and northeast, following the Cheremis and Votyaks. Having stopped at the turn of the Volga, they occupied the territory of the present Nizhny Novgorod Region and Chuvashia, as evidenced by local place names. The Erzia’s traces are particularly clearly expressed in the Nizhny Novgorod region, not to mention the Mordovia. The layer of Mordovian toponymy here is so dense that the coverage of this issue is a special topic. Here are just a few examples. The name of the town of Arzamas, obviously, comes from the ethnonym Erzya, but that means the second part of the word – it is not clear. The town of Kstovo was certainly evolved in the old settlement of Strawberry Fields, receiving the name of Erzya kstyi and Moksha ksty "strawberry" (the suffix -vo, obviously, has Slavic origin). Erzya ley "river" is present in the name of the Shemley River, lt of the Ozerka, rt of the Kudma, rt of the Volga. This element is found in many place names as in hydronyms and oikonyms on the right bank of the Nizhny Novgorod Region (Kavley, Kudley, Motyzley, Seley, Tartaley, Shemley, Chuvakhley, etc.). The name of the village of Kuzhadon in Dalnekonstantinov district can be explained by Erzya kužo, Mok. kuža "glade". The names having the root vele, vile descended from Erzya vele "village". The river Modan, rt of the Seryozha, rt of the Tesha, rt of the Oka – from Erzya, Moksha – moda "land".

Shown above picture of the migration of Finno-Ugric peoples to contemporary habitats is well confirmed also by the location of the Finno-Ugric toponyms decrypted using only one of all the Finno-Ugric languages (see Google Map below).

Finno-Ugric place names on the ethno-producing areas and migration routes of the Finno-Ugric peoples.

On the map, the place names left by certain Finno-Ugrian peoples during the formation of their primary languages are denoted by points of different colors in accordance with the languages in which they are interpreted. For the individual languages, the following colors are adopted: Finnish – dark blue, Sami – yellow, Estonian – burgundy, Veps – red, Hungarian – green, Komi – khaki, Moksha – pale violet, Mari – blue, Khanty – brown. The boundaries of the common Finno-Ugric territory are marked in blue, and the boundaries of individual areas are represented by river lines. The color of the lines is black or corresponds to the color of the language in which the river name can be explained.

Placing place names confirms the picture of the settlement of primitive people, painted by Morgan. The Finno-Ugric toponymy, as well as the Bulgarish, Anglo-Saxon ones are characterized not only by clusters in a certain place but also by well-shown chains that mark the paths of people's settlement. In chains, settlements are separated from each other, indeed, at a short distance, which ensures close contact between the departed and the remaining population, which contributes to the preservation of a single language. The paths laid by the pioneers in some cases, thanks to continuous improvement over the course of technical progress, have survived to our times. A good example is an M9 way, which runs from Moscow to the Baltic states, along which there is a clear chain of toponyms of Estonian origin. The road goes over rough terrain, and this suggests that not only physical-geographical but also socio-geographical factors determined the migration routes already in ancient times.

Another addition to the picture of Morgan. Not only relative overpopulation of certain areas but also the invasion of foreign-language tribes drive the aboriginal population if it is culturally inferior to the newcomers. In our case, an example would be the displacement of Veps by new arrivals Bulgars, who stood at a higher level of development. Initially, the way of resettlement of the Bulgars was determined by natural conditions. The map shows that they moved along the banks of the Desna and the Oka Rivers, but having come thus to the territory of the Veps and finding it convenient for settlement, the Bulgars remained here for a long time. They did not penetrate into the Finnish area despite the possibility. This is evidenced by the almost complete absence of Bulgarian place names there and quite numerous Finnish names.

Sure, the certain psychological barrier was the passing of the Volga River to be considered as a border of the known populated world. But under the pressure of neighbors, the ancient Finno-Ugric tribes, first of all, Mansi, Khanty, Sami, searching for new places for hunting and fishing, passed this water barrier. Finding auspicious conditions, they continued the gradual movement on open spaces of Northern-East Europe. The ethnic groups of Finno-Ugers moved, exact as other people during migration, in the order determined by the places of their former habitats, not out-distancing one another and especially not remaining behind. Staying more a long time in the places with favorable conditions, some clans were separated from the language relatives, and certain changes in their languages arose and this led to the formation of new dialects. In such a way, the languages of the Karelians, Izhors, Livs, and Vods could have been formed in the territory between the Northern Dvina River and Baltic Sea. Small groups that lagged behind the main tribe were assimilated by more numerous newcomers. Apparently, the migration of the Finno-Ugric people was so slow that people did not even realize their movement in certain directions, staying for a long time in new places of the settlements.

Finno-Ugric place names give us a wealth of material for thought. By carefully examining the most commonly used words for place names, one can get certain ideas about the culture, economy, and even the psychology of migrants. The most common among the Finno-Ugric place names is Kashino, similar to Rus. kasha “porridge”. In the European part of Russia, 31 settlements have been recorded having this name. It is unbelievable that at the base of the most common toponym lay such a very prosaic word as “porridge” what is possible only in some cases. Most likely this name originated out of Old Fin. *kaski, what is also confirmed by the numerous place names of Kaskovo (Koskovo), which retain the original combination of consonants sk, reflected in most cases in sh what is a common occurrence. Finnish kaski and Veps kas'k have the meaning of "a forest plot, cut down and cleared for arable land". The resettlement of the Finno-Ugrians began even when they did not know slash-and-burn agriculture, so the original meaning of this was was different. Est. kas'k means "birch", as if semantically quite distant. However, the Finnish kaski in some cases is used to name the young birch. A birch forest could develop on clearings, not necessarily intended for agriculture. If you take into account Mordvin kuzha and kuzho "a glade", then we can assume that the original meaning of these words was just that, and later it developed into a cut-down place in the forest, and then onto young birch trees during the cutting site and eventually birch trees in general. Then the Russian kasha, which does not have a reliable etymology, should be borrowed from the Baltic-Finnish kaska. No wonder a common Russian expression "birch porridge" exists.

Spread of sites of Bondarikha culture

Fragment of the map inArchaeology site

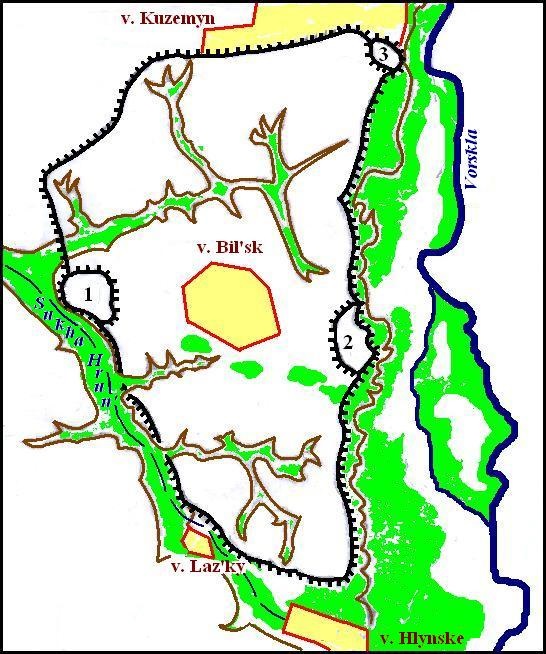

Judging from the scant place names, Mordvinic tribes occupied the left bank of the Sula and the basin of the Psyol and Vorskla rivers, i.e. north-western part of the Bondarikha culture. Such localization of Mordvinic settlements gives the warrant to bind confidently known the Bilske settlement with the city of Gelonos described by Herodotus. This hypothesis has been long advanced by B. Shramko (SHRAMKO B. P. 1987), but V. Il’inski has proved its failure (IL'INSKAYA V.A., 1977: 91-92).

Herodotus asserted that the wooden city of Gelonos was located in the country of Budinoi and hillfort Bilske lies at the old channel of the Vorskla River opposite the town of Kotelva in Poltava Region.

Left: Map of Bils'k hillfort according B. Shramko (SHRAMKO B.P. 1987: 24, Fig. 2.)

Number mark

1. Western fortification.

2. Eastern fortification.

3. Kuzemyn fortification.

Oriental ramparts run along steep banks of the Vorskla River, and Western ones- along the dry bed of the Sukha Hrunl River.

The Budinoi are considered to be the forefathers of Mordvins. Therefore Mordvinic epic about the building of a large city (MASKAYEV A.I., 1965: 298) confirms the made hypotheses.

The Bondarikha culture, which existed in the interval 1200 – 800 years BC, is associated with its predecessor Maryanovka one, which relics are found on the Desna, Seym, Sula, Vorskla, Sev. Donets and Oskol (BEREZANSKAYA S.S., 1982: 41).

There the Bondarikha culture goes out beyond the border of Maryanovka one between the Sula and Desna. It was here that the Lebedivka culture was located later, which bearers were defined as the Anglo-Saxon. Coming on the left bank of the Dnieper the Anglo-Saxon pushed the Mordvinic people beyond the Sula, but maybe also assimilated its remnants, as reflected in the lexical correspondences between the English and the Mordvinic languages which can not be explained otherwise. Later, apparently, Mordvins had to return to their ancestral lands and further to the territory of the present-day Mordovia

The stay of the Anglo-Saxons in the vicinity of the Finno-Ugres was to have a consequence of lexical correspondences between the Old English and Finno-Ugric languages. For example Mari pundo "money" can be correlated with OE. pund "a pound, a measure of weight and a monetary unit." This word could reach the Mari through the Mordva, whose languages have pandoms "to pay", pandoma "fee", borrowed from the Anglo-Saxons. Other Germanic languages have similar words. It is believed that this is an early borrowing from Latin, which have pondō "pound" and pondus 'weight" (KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989, 542). However, there are other facts that require explanation. For example, Mar. archa "chest" corresponds to Lat. arca "box, chest", but it can be borrowed from other languages (Chuv. arca "chest", OE earc (e) "ark, box"). Mar pod, Fin. pata and the like in other Finno-Ugric languages in the meaning of "cauldron" also have a correspondence in Lat. pottus "pot". The Latin fundus “bottom, base” corresponds well to Mar. pundash "bottom, sole". From the Mari this word got into the Komi and Udmur languages - Komi pydös, Udm. pydes "bottom". The assumption that these words were borrowed from Iranian dialects (UKHOV S.V. 2014: 13-14) is erroneous. Separate Mari-Latin correspondences can be as follows: Mar. vurgo "stem" – Lat. virga "rod", Mar. rat "sense" – Lat. ratio "mind, thinking", Mar. tuto "full" – Lat. totus "whole".

The ancestral home of the Mari was identified in the area bounded by the Don, Voronezh, and Khoper rivers. At some time, they began to migrate to the places of their present habitat. On this path, toponyms were found that have no interpretation either in the Finno-Ugric, or in Russian, or in the Turkic language, but are deciphered using Latin. Among them: Alamasovo, Ardatov, Virga, Volonter, Kandievka, Kondol, Penza, Ruzaevka, Satis. This strange phenomenon made it possible to assume that some part of the ancient Italics from their ancestral home crossed the Dnieper and moved northeast towards the Volga. It can be assumed that they migrated with the Cheremis or followed them (for more details about the presence of the ancient Italians on the territory of Russia, see section Ancient Greeks and Italics in Ukraine and Russia). Some place names of alleged Italic origin form a cluster around the sity of Penza. They were not found on the territory of the Republic of Mari El. Obviously, the Italics, having passed part of the way together with the Mari, stopped further movement, finding convenient places for settlement in the Penza region. One way or another, the ancient Italics left enough evidence of their stay in the neighborhood with the Mari. To the above words, you can add the words of the Finno-Ugric languages consonant with Latin rūmigāre "to ruminate", which comes from rūmen "throat, esophagus". Both Latin words correspond to the Old Ind. romanthah "rumination" (WALDE ALOIS, HOFMANN J.B., BERGER ELSBETH, 1965). In the Finno-Ugric languages, the same meaning have Veps. märehttä, Est. mäletseda, Karel. märehtie, Fin. märehtiä, Komi römidztyny, Udm. žomystyny. Experts believe that they all have a common origin, but the diversity of their forms does not find historical argumentation and therefore there is no confidence in the reconstruction of the original Finno-Ugric root: *märз or *rämз (HÄKKINEN KAISA, 2007: 759). Kaisa Häkkinen, the author of the etymological dictionary of the modern Finnish language for some reason did not introduce in this cluster Erzya and Moksha words r'amigams "ruminate". The similarity of the Mordovian words and the Ukrainian "remigaty" makes it possible to assume that the Finno-Ugrians borrowed the Ukrainian word through Mordovian, but it was borrowed from Romanian in historical times and therefore could not be widely spoken in the now very remote Finno-Ugric languages. The fact that the Romanian word comes from the Latin no doubt (MELNYCHUK O.S. (Ed). 2006, 140). Finno-Ugric words could not be borrowed from Indo-Aryan due to a large phonetic difference. Under such circumstances, the words with the meaning "ruminate" could get into the Finno-Ugric languages only from Italics".

At right: Habitats of the Greeks and Italics in Ukraine and Russia

On the map, the ancestral home of the Greeks and their later settlements are marked in blue, the Anglo-Saxons – in red. The ancestral home of the Mari is marked in yellow, and the territory of the Republic of Mari El is orange.

The English word fang could evidence in favor of the contacts of the Anglo-Saxon with the Mordvins, because similar words meaning "tooth" are present also in the Finno-Ugric languages (Mansi puŋk, Khanty pöŋk, Hung fog, Lap pānnj, Udmurt, Komi pin'). In Mordvinic this word has the form pey but earlier it could sound different, because the Talish language has word pingə "fang" which could be borrowed only from Mordvinic (other Iranian languages have no similar word). However, it is believed that the meaning "fang" of the English word had evolved from OE fang "hunting, spil" which stayed semantically enough far. It is interestingly that Old English had another word for "fang" of unknown origin. It may indicate the presence of the Anglo-Saxon in eastern Europe, because there is a group of words of different meaning but deriving from the Turkic čočqa "pig" – Os tusk'a "a boar", Hung tuskó "stump" Moksha shochka, Erzya chochka "a log" which correspond to the OE tūsc "fang" (yet Ung tüske "thorn", Veps t'ähk, Fin tähkä "a spike").

A good argument in favor of Anglo-Mordvinic contacts is the correspondence of archaic Eng leman "a lover" and Mordvinic (Moksha and Erzya) loman’ "a man". At first sight, this is a distant relation, but it is not so. Ossetic also has the word meaning "a friend, lover" similar to the English word - lymän. This word has no matches in other Iranian, but V.I. Abayev asserted that it originates from Ir. *fri “to love” (Av. fri-, frinati “to give joy, love”, Pam. fri “good, dear”, Sak brria- “dear” a.o.). He has construсted from the Proto-Iranian form a non-existent participle *frīymana, which supposedly turned into Os. lymän. He also assumes the borrowing of the Ossetian word in the Mordovian language already in the sense of “man” [ABAYEV V.I. 1973: 54-55]. All this looks too far-fetched. In fact, the origins of words can be found in OE el "alien" and mann "a man." The Morodvin word has correspondences in several Finno-Ugric languages having meaning "a man" or "a stranger" (Vep łaman, Lap olmenč, Mari ulmo, Moksha lomanen’, Mansi elm). Thus it seems surely that the Mordvinic word was borrowed from Old English *elmann, and then spread among other Finno-Ugric peoples and came to the Ossetians too. It may be noted that the semantic relationship of words "a friend" and "a stranger (man)" is understandable, because in ancient times friendly relations always existed between members of different ethnic groups (kunaks). Subsequently the Anglo-Saxons borrowed from the Ossetians the word lymän and understood it only as “lover”.

Here are yet a few possible Anglo-Mordvinic matches:

OE ampre “sorrel” – Mok, Erz umbrav “sorrel”;

OE glæs "glass" – Mok klants’ "glass",

OE lætt "a lath" – Mok lata, Erz lato "roof, fore-roof";

OE maser "maple" – Mok maraz’ "Tatar maple",

OE pǽl, pal“a post, pole”- Mok p’al "a stake";

OE sot "soot" – Mok, Erz sod "soot",

OE tōl "a tool" – Mok tula, Erz tulo "a wedge".

The above examples of Finno-Germanic language connections are only a small part of their entire block. Experts also find matches in the biological nomenclature, in particular, in the names of trees and fish, and are forced to give hypothetical explanations for this phenomenon:

… some of the groups of bearers of Proto-Finnic and bearers of disintegrating Proto-Germanic, respectively Proto-East-Germanic and Proto-North-Germanic could have lived in the last century BC a half-nomadic life in close proximity on the vast space-continuum between the rivers Dnieper and Volga in the South-East up to the Vistula and Baltic Sea in the North-West (ROT SANDOR. 1990: 25).

Archaeological sites of the Magyars have been found in the Lower Kama land and the Bashkirian Urals. We are that "Old-Hungarian tribes appeared in the Western Urals area no earlier than the turn of the 6-7th centuries and remained there until the thirties of the 9th century AD" (KHALIKOV A.Kh., 1985: 28). However, this does not imply that the Magyar Urheimat was somewhere in the Urals, as many believe, including the Hungarian scientists (VERES P. 1985).

Maybe, the opinion about the Ural Urheimat of Magyars has been formed on the warrant of the obvious and far-reaching influence of Turkic languages on Hungarian at the conventional assumption, that the native land of Turks was somewhere on Altai. This assumption resulted in a notion about the Volga-Ural region of cultural and linguistic interaction of the Uralic and Altaic ethnoi (GARIPOV T.M., KUZYEV R.G., 1985). But, as we have seen, the Urheimat of Magyars was in Eastern Europe, their first contacts to Turkic speakers occurred just here, instead of nearly of the Urals. The existence of certain linguistic contacts between the Magyars and the Indo-Iranians going in the more distant past allows the possibility that the Hungarians could cross the Volga already at the historical time. Specialists have long known the special Hungarian-Ossetian language connections, but more important for the determination of the Magyar settlements are the connections of the Hungarian language with Kurdish, Talyshi, and Gilaki. The most convincing examples of possible Hungarian-Iranian lexical correspondences are shown in the table below.

Table 9. Hungarian-Iranian lexical correspondences.

| Hungarian | Kurdish |

| bitorol – to usurp | Kurd bîtir – to get |

| csipö – thigh | Kurd çîp – calf (a parf of leg) |

| csiriz – shoe glue | Kurd çirîsk – glue |

| csirke – chicken | Kurd çêlîk – nestling |

| dúc – slanting supporting pole | Kurd doş – slope |

| épit – to build | Kurd ebinî – construction |

| hó – month | Kurd hov – month |

| lomb – leaves | Kurd lam – leave |

| méreg – poison | Kurd merk – poison, Osset. märg – poison |

| száraz – dry | Kurd şorax – dry |

| teher – load | Kurd tex’ar – weight |

| mezö – field | Tal. məzə – field |

| nиz – to look | Tal. nəzə – to see |

| terel – to drive | Tal. təranən – to drive, Osset. täryn – to drive |

| vad – wild | Tal. vaz – wild |

| rem – horror | Gil. rəm – horror |

| rés – chink | Gil. rəxnə – hole |

| veszte – death | Gil. vəsta – to end |

| vasal – to palm | Gil. vasen – to smear |