External Influences on the Language and Culture of the Ancient Slavs

The Urheimat of the Slavs, determined using the graph-analytical method, was located on the banks of the Viliya River, the right tributary of the Neman River in the neighborhood of the ancestral homeland of the Balts. Slavic-Baltic linguistic connections persisted throughout history. Their relationship was so close that it gave reason to talk about a special Baltic-Slavic unity. In this regard, the stratigraphy of mutual borrowingі is very difficult and is the work of specialists.

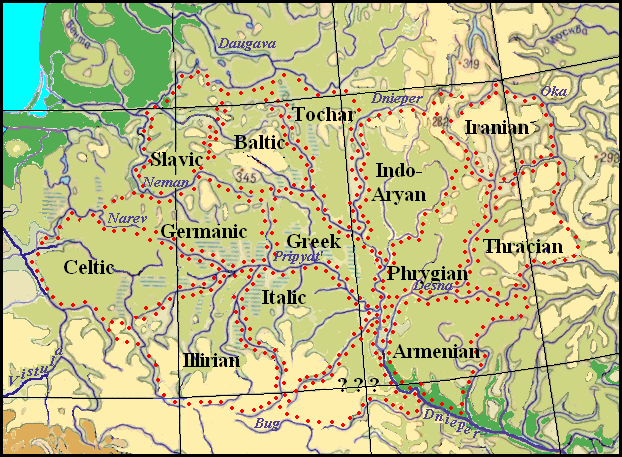

The map of the Indo-European space.

In addition to the Balts, the nearest neighbors of the Slavs were the ancient Germanic tribes of the Goths. The area of the ancestors of the modern Dutch and Frisians also was not far. It was located not far on the banks of the Western Bug River. This is supported by loan words from these languages into Proto-Slavic. Loan words from the Gothic language are numerous and well-known, but the Dutch language preserved signs of an old neighborhood with the Slavs too. Slavic word verba "a willow" has correspondences in the Baltic languages in a narrower meaning (Lith. vīrbas "rod, stem", Let. virbs "wand, stick") and exact match in Dutch werf "willow". In the etymological dictionary of the Dutch language, the last connection is noted, but related words from other Germanic languages are not given and at the same time far correspondences are given in Gr. ραμνοσ "thorn bush" and Lat. verber "whip" (VEEN van P.A.F., SIJS van der N. 1997: 970). A Dutch match is not mentioned in the Russian etymological dictionary, but other correspondences from Greek and Latin are given (Gr. ραβδοσ "staff, stick", Lat. verbena "leaves and shoots of laurel") (VASMER M. 1964: 292). The close connection between Dutch and Slavic words is obvious. Slavic words zvon "ringing", maly "small", olkha "alder" have good correspondences in the Dutch language: zwaan, maal, els, while similar words of other Germanic languages stay farther phonetically.

Occupying the locality around the Masurian marshes on the Kashubian upland and along the Baltic coast, away from the power centers of civilization, the Slavs carried out patriarchal life as hunters and fishers for a long time. They were undoubtedly aware of livestock, but arable farming, if existed, had very primitive forms. It is known that the folk exorcism keeps deep depths of popular culture and reveals that "the agrarian magic of the Slavs was deposited in known us magic idioms only in a minor extent", while "the fish is represented in a very archaic view of the world" (NOVIKOVA M.O., 1993: 219). Evidence that the Slavs did not know many cultivated plants are their names borrowed from the later neighbors. None of the names of the cultural cereal has satisfactory etymology on a Slavic basis, not to mention vegetables and fruits. Contrariwise, Slavic loan-words in German for the names of fish say about the great importance of fishery in the Slavic economy. Giving examples of such names as Ukelei, Plötze, Peissker, Sandart, Güster, Barsch etc, A. Popov points out that adoption of these words occurred during the process of the Germanization of the Slavs Slavs in Central and Eastern Germany, "when the Slavic fishermen longest resisted this process" (POPOV A.I., 1952: 72).

There were on the territory occupied by the Slavs many lakes and small rivers therefore the population had no problems with nourishment. especially since fish products after simple processing lend themselves well to storage. The sufficient feed inevitably resulted in rapid population growth and the Slavs left their homeland for a long time because fisheries provided much greater opportunities for food than hunting. Information for North America evidences that the density of the population engaged in fishing is 3-4 times higher than that of hunters (BROMLEY Yu.V., 1986: 446). So when the Slavs had reached the level of "maximum economic function" their number was very large. This explains the fact that the Slavs settled eventually a vast space from the Vistula River to the headwaters of the Oka.

There is documentary evidence of fish abundance on Slavic territory, although in more recent times, there is no reason to think that the fish were less before:

The abundance of fish in the sea, rivers, lakes, and ponds is so great that it seems just incredible. You can buy for one denarius a whole cart of fresh herrings, which are so good that if I were to tell everything I know about their smell and thickness, it would risk being accused of gluttony (HERBORD, 1961, II, 41:315).

The preferential occupation of fishing in the terrain rich in different water basins shaped largely the distinctive psychological features of the Slavs. Fishing does not require the combined efforts of large groups, and abundant fish stocks of rivers and lakes precluded a brutal struggle for land, as it was, say, among the nomads. Accordingly, unlike their contemporary nomadic folks, Slavs were more peaceful, but at the same time independent and democratic, which was more disadvantage as an advantage at that time. These features of the Slavic were noted by Byzantine historians, describing the Slavs as follows:

These tribes, the Slavs and the Antes are not managed by one person, but from the beginning live in popular sovereignty, and because they have happiness and unhappiness in life is a common cause… Their lifeway is, like Massagetae, rude… but in fact, they are not bad and not evil (PROCOPIUS of CAESAREA. 1961: III, 14).

The nations of the Slavs and the life in the same way and have the same customs, in their love of freedom. They are both independent, absolutely refusing to be enslaved or governed, least of all in their land. They are populous and hardy, bearing readily heat, cold, rain, nakedness, and scarcity of provisions… Owing to their lack of government and their ill feelings toward one another, they are not acquainted with an order of battle. They are also not prepared to fight a battle standing in close order or to present themselves in the open and level ground (PSEUDO-MAURICE. 1961: XI,5).

.

Along with fishing, the Slavs were engaged in beekeeping, as was pointed out by M. Pokrovsky, paying attention to the common Slavic names of bees, honey, and beehives. These words were inherited by the Slavs from Indo-European roots, which may indicate old and long times of their beekeeping engagement. This kind of business made it possible in the forest zone to provide large amounts of nutritious products for the long winter. Wild bees made up the majority of the owner's property and special idioms were used to transfer them in legacy, examples of which are preserved in the Sorbian languages (POPOWSKA-TABORSKA HANNA. 1989: 168).

Bee-keeping is also a purely individual and especially peaceful occupation and also influenced the formation of the psychology of the Slavs, which certain features are been a little noting a now but two centuries ago one talked about them without hesitation:

They (the Slavs – V.S.) were kind-hearted, hospitable to the point of waste, lover of rural freedom, but submissive and obedient, of stealing and looting alien (SCHAFFARIK PAUL JOSEPH. 1826: 16).

However, the Slavs were not alien to the teamwork and mutual support in public life, as also evidenced by Slavic vocabulary. For example, the Russian word orava "crowd" in the Kashubian language means "mutual neighbor help when plowing". The same is also evidenced by the Ukrainian word toloka, which is in the same Kashubian means "mutual neighbor help during harvest" (POPOWSKA-TABORSKA HANNA. 1989: 168).

Populating the peripheral areas of common Indo-European space for a long time, the Slavs stayed almost without cultural influences of the civilized world, which was generally located further south from their settlements:

The geographical position that the Slavic peoples occupied for many centuries did not allow them to go hand by hand with the Romance and Germanic tribes (KOSTOMAROV N.I. 1890: 275.)

This point of view was held by many other scientists who seriously studied the culture of the Slavs on the basis of historical, archaeological, ethnographic, and linguistic sources. Czech Slavist Lyubor Niederle concluded that "the Slavic culture has never reached the level of the adjacent ones, could not equalize with them on wealth and has always been poorer than eastern cultures, as well as the Roman, Byzantine, and even German cultures" (NIDERLE LUBOR. 1956). We will return to the problem of the backwardness of Slavic material culture further, but now only indicate that the spiritual culture of the ancient Slavs, respectively, was very low, as it is evidenced by custom to kill children and the elderly, by the remains of phallic worship, promiscuity, polygamy, polyandry. The remnants of such customs long preserved in Russia, Ukraine, and the Balkans (NIDERLE LUBORЪ. 1924: 31, 36, 75-76). According to some sources, cannibalism was also not uncommon, although this was denied by L. Niederle (Ibid. 75-76). Poor Slavic mythology confirms the lack of development of the spiritual culture of the Slavs:

… it should be said that the Slavs really did not develop their mythology; their ancient religious ideas are primitive demonology, in which one should rather see an ancient peculiarity better preserved by the Slavs. This allows us to more soberly assess the data of late classical mythology. It would be strange to try to rehabilitate such a state of Slavic mythology or to see something shameful in this “lag” of the ancient Slavs. (TRUBACHOV O.N. 2006: 11).

Ancient rituals and the daily life of the Slavs are of a magic tinge with the participation of various wizards, sorcerers, healers, as also indicated by the rich Slavic vocabulary, while the word bog "god" is quite a late borrowing from some Iranian which have the root of the word bag "gift", "give". There is a lot of controversy about the possibility of the existence of a Pan-Slavic god Perun, but there are few linguistic facts for such an assumption.

The low cultural level of the ancient Slavs is reflected by the lexical composition of their language. For example, the Proto-Slavic language has no words for expressing gratitude and the concept of duty. Ukrainian words diakuvaty "to thank" and musyty "to must", which have matches in all West Slavic languages and in Belarusian, are of Germanic origin. The eastern, left-bank branch of the Slavs does not have common words of similar sense. They appear in the South Slavic and in Russian languages already in historical times after the inhabiting of the Slavs of this branch over wide spaces, which indicates their absence during the time of their close proximity to the ancestral homeland. Polish linguist A. Bruckner, speaking of German origin Pol. musić, wrote: "the anarchic Slavs have no word for duty, permission; they loaned it (cf. Old Chech. dyrbjeti from Ger. dürfen "to be allowed")". Speaking about the borrowing time of the Pol. dziękować, he argued that it happened around XIV cen. (А. BRÜCKNER ALEKSANDER, 1927: 348, 112). That Ukrainian words diakuvaty and musyty have Germanic (German) origin, all Slavists agree, but it was believed that they got into the Ukrainian language through Polish (MELNYCHUK, A.S. 1985: 153). Thus, it is assumed that Ukrainian and similar Belarusian words originate from Polish dziękować and musić. However, the presence of these words in the Transcarpathian dialects refutes this explanation, and therefore, Ukrainian scientists delicately avoided this question by the side. For example, in solid work on the history of the Ukrainian language, there is not a word about them, despite the fact that the origin of many other less common words is considered (RUSANIVS’KIY V.M., Ed. 1983). Ukr. diakuvaty clearly differs phonetically from Pol. dziękować what could not be, if the latter was formed only in the XIV century, and then penetrated into the Ukrainian and Belarusian languages. Such late borrowings mainly preserve the semblance of Polish, for example, West Ukr. ciocia, gemba, piec a.o. In the paper, especially devoted to the mutual borrowing of Polish and Ukrainian languages, there is no mention of the words diakuvati and musyty, perhaps, the author did not consider them as Polish loan-words (LESIÓW MICHAŁ, 2000, 2000, 395 -406)

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian word diakuvaty is a perfect example of the historical development of Slavic vocalism well researched by scholars. Considering the laws of this development, we can easily ascertain that this word was derived not from Ger. dank-, but from Gmc. *þanka. A diphthong -an in the borrowed Germanic word, according to the law of an open syllable, based on the principle of increasing sonority, had turned in Slavic language in some nasal vowel reflected by the letter "jus small" in Church Slavonic. This sound exists in Polish till now being conveyed by the letter ę. The Gmc. þ was reflected in Slavic languages as palatalized d’ (in German, by the way, – in d, and in English – in θ). Accordingly, we have now such Polish form dziękować, and similar Old Ukrainian word had the form *d'ękowatь. It is known, that nasal vowels have disappeared in the Ukrainian language, as well as in many other Slavic languages, and the "jus small" has coincided with ya, and the form diakuvaty occurred. A. Brückner explained Pol. dziękować as a derivative from Cz. dik, dieka. To explain Polish nasal ę, he supposes existence for that time nasal vowels in the Czech language. However any pieces of evidence about the existence of the nasals in the Czech language at that time are not found, and they have disappeared in East-Slavic languages, e.g. in the middle of the 10th century. The processes, which passed in Slavic vocalism according to the tendency of growing sonority, have ended during the disintegration of Proto-Slavic language unity. Thus, the borrowing of Ukr. diakuvaty and other similar west Slavic words have taken place approximately in those days when the Slavs have inhabited former lands of Germanic peoples. However, before that, some Baltic tribes dwelled there and later completely disappeared among the Slavs. Obviously, the Germanic word came to the Slavs through these Balts. The establishment of the time of borrowing word musyty is impossible for the present, as it has no specific phonetic features. However, by analogy, we may assume, that its borrowing occurred at the same time.

The origin of the the Ukrainian words bešket "roistering", bešketnyk "a brawler" is interesting too as analogues to them are not present in any other Slavic languages. The more so that, they are been presented mainly in the East Ukraine. The origin of these words is considered not fully understood (MELNYCHUK O.S. 1982: 180). However, before looking for the origin of them we have to remember that typical for the Western Slavic languages the word škoda was borrowed from Germ *skaþуn which has match in modern German Schaden. This borrowing happened till the time when Gmc. sk began to be spelled as š. Ukr. skyba (Gmc. *skábó(n), German Scheibe) has been borrowed at that time too, while in contrary Ukr. words šyba, šybka having the same Germanic root which were borrowed through Polish from German at later time, after the transition sk in š. The transition sk in š in the German language has taken place in the 5th – 6th centuries AD (SCHMIDT WILHELM, Ed. 1976: 175). Thus, Ukrainian šk/sk in ancient Germanic loan-words corresponds sch of modern-day German. Let us return now to the word bešket. A. Potebnia believed, that this word is borrowed from Germ. Beschiss “cunning, lie”. M. Vasmer, doubting this, believed the word was borrowed from Middle Upper German where beschitten "to deceive" is present (VASMER M., 1964). Return transition š in sk in loan-words in the Ukrainian language is poorly probable, besides the senses of German and Ukrainian words are remote enough. Most likely Ukr. bešket is verbalized noun from the verb bešketuvaty "to roister" which has good phonetically and semantic match in Germ. beschädigen "to damage, spoil" and, thus was asrisen from the same German root as the word škoda.

Obviously, Slavic loanwords in Germanic languages had to exist. Known German borrowing such as Grenze "border", Kummet "clamp", Quark "cottage cheese", Petschaft "seal" as fish names mentioned above and borrowing in Norse torg "market" come from historically recent times. More ancient loanwords are unknown, perhaps this topic is not specifically studied. In the course of our studies, attention has drawn to the similarity of words. Slav děva "a girl" OE. đeowu, which has matches in other Germanic languages. Holthausen translated the Old English word as "Magd" (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974, 363), which means "a servant girl" in modern German. However, initially, it meant "being female from early childhood to marriage" (A. PAUL HERMANN, 1960, 387). The first vowel of this word in Old Church Slavonic language was reflected by the letter "yat", which was pronounced as a diphthong or as a long vowel, ie phonetically OE đeowu could well correspond to the Slavic word. Slavic, not the Germanic origin of the word is affirmed by that this word is absent in modern Germanic languages, sure it was rarely used. In addition, the meaning "servant girl" may indicate that the ancient Germans took Slavic girls in maid and also called them by the Slavic word. Accepting it by Germanic languages gives reason to believe that giving girls as servants were common, and the reason for this could be many children in Slavic families. In the end, such a situation has led to an overpopulation of the land and further mass expansion of the Slavs, which assimilated the previous population in many places. Such an assumption contradicts the existence OE đeo(w) "servant", of unclear origin. However, it can be assumed transferring the primary sense to male servants.

Except for the Baltic substratum, language influences on Proto-Slavic were made by the languages of the adjacent to the Slavs population. Now we know that the steppes of Right-side Ukraine were being occupied by the Scythians-Proto-Chuvashes before the Slavs here. The Cimmerian-Kurds stayed in the adjacency with the Proto-Chuvashess for a certain time too. The language influences of the Proto-Chuvashes and ancient Kurds can be seen in not explained loanwords in the West Slavic languages. Slavic-Kurdish language connections are considered in the subsection Cimmerians. Here we will consider some Slavic-Proto-Chuvash language connections. The Slavic-Turkic connection was noted for the first time by Czech researcher J. Peisker who created the original theory of Slavic-Turkic relation which has been described in his paper "Die ältesten Beziehungen der Slawen zu Turkotataren und Germanen" (PEISKER J. 1905). His sights have been criticized, in particular by L.Niederle, as they supposed that Slavic-Turkic contacts could not exist if to be saying about some "Turan approach". Now we know that the contacts of the Western Slavs with Turkic Scythians have a real basis and explanation. Certainly, Turkic language influences on the Slavs cover a very wide period and it is difficult to separate old and latest loan words which are widely present both in South-Slavic and in East-Slavic languages. However, the presence of Turkic words in West Slavic languages is very indicative. Turkic words could infiltrate into the Polish language through Ukrainian, and into Slovak and Czech through Hungarian. For example, Slvk. čakan "a mattock" of obviously Turkic origin (Chagat. čakan "a fighting axe"), but as Hung. сsakany exist, this word cannot be taken in attention. The same is to say about Slvk., Cz. salaš, Rus. šalaš "a hut" which has matches both in the Turkic and Hungarian languages. Such words are numerous, however, Machek’s etymological dictionary encloses examples of Turkisms whose ways of infiltration into the Czech and Slovak languages remain enigmatical (MACHEK V. 1957). In this situation, special attention should be paid to the linguistic (mainly lexical) matching between the Chuvash and the West Slavic languages. Just Slavic matches to Chivash words will be considered in this study. Borrowing could be mutual.

Let's consider some Slavic-Chuvash matches which can be very interesting. Lonely among Slavic languages Slvk. sanka "the bottom jaw" can have Proto-Chuvash origin as the word sanka "a frontal bone" is present in Chuvash stemming from Old. Turk. čana "a sled", "a jaw" but ending -k is characteristically only for Chuvash and Slovak. Slovak loša "a horse", Ukr. loša “a foal” are considered to be borrowed from Turkic languages as alaša "a horse" is present in Turkmen and Tatar, but the falling initial a is not clear there. Borrowing this word from Proto-Chuvash (Chuv. laša "horse") explains this falling. Another name of a horse kobyla which matches only in Latin (caballus), in Machek’s opinion, also has a Turkic origin. A source of loan both in Italic and in Slavic languages can be Proto-Chuvash.

As Turkic people have been engaged in horse breeding long since, Slavic khomut and Germ. Kummet “horse-collar”, whose origin is unclear, can also stem from Proto-Chuvash (cf. Chuv. khomyt). Some researchers consider, that Slvk., Cz. kolmaha, Pol. kolimaga, Ukr. kolimaha, Rus. kolymaga (all – “a cart”) are ancient loan words from the Mongolian language (Mong. xalimag "high carts – tents") through Turkic intermediary (MELNYCHUK O.S., Ed.,1982-2004). At such an assumption, the Mongolian word should pass through the whole chain of Turkic languages. It is improbable, that it has disappeared in all of them without any track. Most likely, Slavic kolimaga can be explained as “harnessed horse”, having taken into account Chuv. kül "to harness" and widespread in many Turkic languages jabak “a horse, foal”. The same origin can have also unclear Ukr. kulbaka "a saddle" and similar words in other Slavic languages. As we already know, ancient Turkic people had advanced vocabulary in hydraulic engineering constructions and floating means. Therefore the Slavic word gat’ “a dam” is borrowed from Proto-Chuvash, as Chuv. kat has the same sense.

The origin of Slvk., Cz. kahan, Ukr. "kahanets" (a primitive lamp with a handle) is not clear too. This word can be compared with Chuv. kăкan "a handle". The Slavic word kniga “a book” is usually compared with Hung. könyv, but on the warrant of a phonetic discrepancy this word could not be borrowed by Slavs. The Hungarian word can be derived, as M. Vasmer and V.Machek specified, from Old Chuv. *koniv ← *konig. Slavic words can originate from the last form. Czech klobouk, Old Slvk. klobúk, koblúk, Rus. Kolpak, and other similar Slavic words meaning "a hat, a cap“ have certainly Turkic origin, but ways and time of borrowing are different. Czech and Slovak words can stem from Proto-Chuvash. It is interesting to compare Old. Cz. maňas “a dandy, a fool” with Chuv. mănaç "proud". V. Machek asserted that the ancient Slovaks borrowed the word osoh "benefit" from the Proto-Chuvashes, but when? M. Vasmer, both V. Machek and A. Brückner consider Slavic “proso” millet of a "dark" origin, probably, even "the Pre-European". Most likely, this word may be connected with Chuv. părça "peas"? Considering Chuv. yasmăkh "lentil", the Slavic name of barley (PSl. jačmy) can also have the Chuvash origin, as well as Sl pyrey “wheatgrass” can (Chuv. pări "spelt"). M. Vasmer supposed that Slav. pšeno “millet meal” and pšenica “wheat”are derived from pkahti “to push”, what is not convincing. Most likely, Psl. pьšeno has the same origin as Chuv. piçen "sow-thistle". Seeds of this plant could be used as food before the spreading of cultural grain crops and its name borrowed from Proto-Chuvashes could be extended by the Slavs on the millet and wheat. Slavic names of cottage cheese (Cz., Slvk. tvaroh, etc.) are also considered to be of dark origin. Hungarian túró stay phonetically far, therefore Hungarian cannot be a source of borrowing, but Chuv. turăkh (fermented baked milk) meets all requirements.

M. Vasmer assumed that Slav iriy (the southern country where birds fly away in the autumn, warm countries) has Iranian origin but its Proto=Chuvash root is more probable. The words ir "morning" and uy "a field, steppe" are present Chuvash language, and words εαρ, ηρ "spring" existed in the Greek language. M. Vasmer thought the initial form of the Ukrainian word was *vyroy. Hence, Proto-Chuvash *eroy could mean "morning (eastern, southern) steppe". When the Slavs still occupied a wood zone saw birds flying somewhere southward, in the steppe in the autumn, they spoke then they flew in "iriy".

V. Machek referred Slvk., Cz. čiperný “alive, mobile” to South Slavic languages without further explanations. Really, čeperan 1) “brisk, mobile”, 2) "swagger" is present in Serbian. But all these words together with Ukr. čepurnyj „beautiful, smartened up ” have a Turkic origin (cf. Chuv. čiper "good", Tat. čiber "good"). A. Rona Tas said that mentioned Turkic words were borrowed from Middle-Mongolian which has čeber "clean, neat" but the Slavic words are phonetically closer just to the Chuvash word. The Slovak and Czech languages have more words which also can have a Turkic origin, but scholars have contradictory opinions about their origin: tabor, taliga, topor, šator, šuvar, šupa.

Karl Menges gives three possible variants of Turkic origin for the word Slav kovyl "feather grass". All three variants are far phonetically and semantically from this word (cf 1. Old. Uigur. qomy “to be in movement”, 2. Alt. gomyrgaj “a plant with an empty stalk”, 3. Tur. qavla “to shed bark, leaves”). The Proto-Chuvash language as a source of borrowing suits more because Chuv. khămăl “a stalk, eddish” is more like to the word kovyl according to the form and sense. For the present, a similar word is revealed only in one another Turkic language (Tat. kamly). It is significant that, according K. Menges, C. Uhlenbek, K Brugmann, W. Lehmann, S. Berneker connected this "dark" word with Gr.καυλοσ, Lat. caulis "a stalk" and within other Indoeuropean words. If we remember that the Proto-Chuvashes had their habitat near ancient Italics, Greeks, and Germanic peoples for a long time, the Proto-Chuvash pre-form can be restored as *kavul which has been reflected in Old Russian as kavyl already at prehistoric times. Another Ukrainian name for a feather grass tyrsa has a Proto-Chuvash origin too. A similar word of the same sense is present in the Chuvash language.

Looking through Vasmer’s Etymological dictionary of Russian one can find out that plenty of Russian and Ukrainian words have matches in the Chuvash language. They can have Proto-Chuvash origin (for example, Ukr. braha, Rus. braga “home-made beer”, vataga” “band, group”, pirog “pie”, khmel “hop”)(VASMER M., 1964-1974). M. Vasmer connects the word braga/braha with Chuvash word peraga "residue, marc" (prior „half-beer, liquid beer”) which has matches Turkic names of weak alcoholic drinks boz/buz. One can also pay attention to certain consonance of Turkic words not only with the Slavic but also with the German names of beverages (cf. N.Gmc bjorr, Ger. Bier, Eng. beer) of unclear origin. Taking into account the phenomenon of the rhotacism in Turkic languages, the proto-form of the name of such beverages should sound something like *borz-, and this explains the form of North German words (correspondence rz – rr is known in Indo-European languages). Consonant words meaning hops ( Rus, Bolg khmel, Ukr. khmіl, Cz, Slvk chmel, etc.) are widespread in many Indo-European and Finno-Ugric languages. Scientists believe that the ways of their spread are very complicated, but agree that one common source of borrowing should exist. Some see it in the language of the Proto-Chuvashes (cf Chuv. xămla “hops"), while others doubt the possibility of penetration of the Proto-Chuvash word far in Europe (Latin humulus, OE hymele, N.Gmc humli). Of course, the reason for doubt gives a notion about the late appearance of the Proto-Chuvashes in Europe. However, discovered proximity to Indo-European and Proto-Chuvash habitats can explain the origin of the names of both hops and beer in many modern European languages. You can also pay attention to the Ukrainian word korchma “inn” which has matches in some modern Slavic languages and is considered to be of dark origin. If we take into account O.C.S krъchьma "strong drink" (MELNYCHUK O.S., Ed., 1982-2004), this word can also occur from Proto-Chuvash (Chuv. kărchama "home-brewed beer," Tat. kärchemä "sour katyk" (the national drink).

Russian word sigat’ "to jump" has an obscure origin. A.M. Räsänen supposed the possibility of its borrowing from Chuv. sik "to jump", but Vasmer objected to it, referring to Belarus sihac’. However, this word is present as well in the Mazovian dialect of the Polish language (BRÜCKNER ALEKSANDER. 1957) and Ukr dial. sihaty widespread in Eastern Ukraine is not necessarily borrowed from Russian. Hence, this word can be also borrowed from Proto-Chuvashes. Vasmer brings together dialect Rus., Ukr., puga/puha "a whip" with a word pugat’ “to frighten”, which originally had the form pužat’. In such a case, the word can be borrowed from Proto-Chuvash (Chuv. puša "a whip"). Such an assumption is especially verisimilar as the Ukrainian has a word pužalno “handle a whip”.

The number of such discoveries is increasing and they are all placed in the list of ancient Turkic-Slavic Language Connections.

Convincing evidence for ancient Slavic-Proto-Chuvash contacts is phonetic and semantic coincidences of lonely among Turkic languages Chuv. salat "to scatter, throw about" with Slvk. sálat’ "to radiate, flare" and Cz. sálat "to flare". Machek submits these words with ancient value házeti, metati "to throw". We shall try to count up the probability of such coincidences for this concrete case. For this purpose, we need to know the certain laws of word formation in the Chuvash language. 2100 Chuvash words have been taken for the analysis of such laws. From them, approximately 210 words begin with the letter s, i.e. the probability of that any Chuvash word will begin from the letter s is equaled 210 : 2100 = 1/10. Having analyzed all words with the initial s it is possible to find the probability of that the second letter of a word with the initial s will be the letter a. This probability is equal 1/6. As it is possible to find probability of that the third letter will be l, and the fourth again a. Accordingly, these probabilities are equal 1/12 and 1/8. Having analysed all words of type kalax, salax, palax, valax where the second a is any vowel, and х is any consonant, it is possible to find probability of that the similar word will end on t. This probability too is equaled 1/10. Having multiplied all these values of separate probabilities, we can find out the approximate value of the probability of appearing the word salat in Chuvash l: 1/10x1/6x1/12x1/8x1/10 = 1/57600. Now it is necessary to count up the probability that the word salat will have meaning close to sense "throw". 2100 Chuvash words available in our list can be shared into groups of words that can answer certain general semantic units. Such division is subjective as the borders between semantic fields are always very dim in a certain measure. However, probably, nobody will object to that the division of all 2100 words into 100 conditional semantic units is sufficient that the semantic field of each of these units in extremely small degree could block another semantic field. Then the probability of that the Chuvash word salat can make sense, close to value "to throw, scatter, quickly to move, or to take off outside, etc." will be equaled, at least it is no more 1/100. Accordingly, the probability of that in the Chuvash language arises a word phonetically and on value similar to Slvk. sálat ’ and Cz. sálat ‘to throw” will be equaled 1/5760000. If we have some similar "coincidences", the probability of their casual occurrence in different languages can be determined by unity with several tens zeroes after a point in the denominator. Practically it means that at good phonetic and semantic coincidences of two words of unrelated languages with five or more phonemes, one of them is borrowed by any way provided that both words have no onomatopoetic character that does the probable occurrence of similar words independently in different languages. For example, the widespread Slavic word duda, dudka “a pipe” is well coincided with Chagat. and Turc. düdük "a pipe". Miklosich and Berneker counted this Slavic word borrowed from Turkic, but Vasmer and Brückner accord of these onomatopoetic words counts as "mere chance". Doubts concerning the loan of a Slavic word from Turkic languages have the basics here, therefore Slav. duda cannot be included in the set of doubtless loans.

If talking about the existence of ancient Proto-Chuvash-Slavic lexical correspondences, we should pay attention to that they were found in both East- and West Slavic languages. This fact not only automatically precludes their explanation as borrowed from Chuvash but also determines the time and place of the Proto-Chuvash-Slavic contacts reflected lexical parallels. The Slavs settled in the basin of the Pripyat in the early 2nd century BC and from that moment they could live near the Proto-Chuvashes. This suggests that only a certain part of the Proto-Chuvashes moved from their old settlements in Western Ukraine to the steppe, while a significant number of them had to remain and not take part in the later migrations of the Proto-Chuvashes in the Sea of Azov and the Caucasus, and then to the Middle Volga. In this connection, we can assume that ancient Slavic influences on today's Chuvash language should not be, and the Proto-Chuvash-Slavic lexical correspondences should be explained only by borrowings from the Proto-Chuvashes. This conclusion is contradicted by Cuv. mixě "a bag" which corresponds to OSl. mѣxĭ “a fur bag”. The presence of the reduced sound at the end of the word suggests borrowing before the fall of the reduced sounds, ie till the 10th-11th century. On the other hand, the word should have been borrowed from the Ukrainian language, where the sound of "yat" (ѣ) was reflected by i, but not from Russian, where it was reflected by e (Ukr. mіkh, Rus. mekh "a bag"). The same example of borrowing from the Ukrainian may be Chuv nimeç "a German" (Ukr nіmets, Rus niemiets). We should admit that the linguistic connections between the Slavs and the Proto-Chuvashes which went to the steppe continued during the first millennium though being weaker. Later, the Slavs expanded their territory and assimilated the remaining Proto-Chuvashes at some time, as is evidenced also place names.

One can also assume that the Proto-Chuvashes and Slavs were also cultural interactions, as was the case between the Proto-Chuvashes and Germans. Chuvash idiom çăkăr tăvar "bread and salt" because of its rhyming should be considered as primary concerning the similar Slavic one. Since such an idiom is many in many Slavic languages, the borrowing occurred from the Proto-Chuvashes. The Slavic cultural influence on the Proto-Chuvashes, who also had to be is not easy to detect because they hide among the later Chuvash borrowings from Russian.

Cultural connections of the ancestors of the Chuvash and Ukrainians are treated separately on a personal website in the section Cultural substratum.