The migration of the Indo-European Peoples in East Europe at the Beginning of the Iron Age

The sequel of the theme

The Archaeological Cultures in the Basins of the Dnieper, Don, and Dniester in the XX – XII Centuries. BC.

The Slavic, Baltic, Germanic, Iranian and Thracian tribes did not participate in The First Great Migration. They only expanded their territories to varying degrees. The largest range was occupied by the Iranians. They settled on the wide space between the Dnieper and the Don. Here on the known ethno-producing areas separate dialects were distinguished from the Proto-Iranian language, which gave rise to current Iranians (see the section Iranic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age ). Almost all Iranians remained in these places for several centuries, but in the XI – X cent. BC. Assyrian sources have already recorded their appearance in Western Iran [ARTAMONOV M.I. 1974: 10].

The reasons forcing the Irano-Aryans to leave their original habitats between the Dnieper and the Don may be different. Perhaps the transition of the Balts and the Anglo-Saxons to the left bank of the Dnieper set in motion the local Iranian population of the Zrubna culture. However, we can think about other reasons. Steppe areas could be abandoned due to climate change, which led to a decrease in the productive possibilities of the steppe. In any case, archaeological data indicate a temporary desolation of the Azov and Black Sea regions:

… in the 12th -10th centuries, BC compared with the previous period the steppes between the Don and the Danube reveal a tenfold decrease in the number of settlements and burials. The same trend of decline in population is manifested in the Pontic steppe also in the subsequent Cimmerian era, which is confirmed by the absence of settlements and stationary burial grounds in this area (MAKHORTYKH S.V., 1997: 6-7).

Thus, the Iranian tribes moved in search of dwelling places with more favorable conditions. Following the first Iranians, their main mass migrated to Asia. The Iranian tribes that inhabited the most northern ranges, the ancestors of the Ossetians, Baluchis, and Kurds, remained the longest in Europe.

The Iranians, like the Turks earlier, used wheeled vehicles to move. Thanks to the invention of the front turning device, the wagons became more maneuverable, which was a technical revolution for that time. Thanks to this improvement, it became possible, on the one hand, to overcome long distances by large groups of people off-road, and on the other, to create new effective chariot fighting tactics, thanks to which the Iranians gained a great advantage over many Asian nations. We defined the area of settlement of Iranians in the territory of the Zrubna culture, but there is reason to believe that part of the population of the Andronovo culture in Western Kazakhstan and Western Siberia were also Iranians, although originally the creators of the Andronovo culture was some Turkic tribe. A significant number of Iranian languages could not be formed only in the territory between the Dnieper and the Don (and even the Volga). Some of them were formed (or separately developed on the basis of European dialects) in Asia. According to the archeology data, the Zrubna and Andronovo cultures are united by the following common features:

• using of chariots;

• the cult of wheel and chariots;

• the cult of fire;

• manual pottery, wood-, stone-, and bone-working, spinning, weaving, bee-keeping, metalworking;

• type of housing – large half-earth-house (KUZ'MINA E.E. 1986: 188).

According to J. Harmatta, the expansion of "Indo-Iranian" peoples from the steppes of Eastern Europe and Asia up to the Indian subcontinent and China took place in two waves. The first wave took place from the beginning of the 2nd mill BC and the second one – from the beginning of the 1st mill BC. It should be noted that the problem of the migration of the ancient Indians and Iranians is confused by the notion of the Indo-Iranian (Aryan) language community. Some scientists believe that its separation occurred after one group of Aryans at the beginning of the 2nd mill BC from Central Asia through the Hindu Kush crossed into India, while some of them stayed in the old settlements, and hence in the 1st mill BC began its expansion in all four directions – in Afghanistan and Iran, to the Urals, Altai, and the Black Sea Steppe [SOKOLOV S.N. 1979-2: 235)].

The close proximity of the Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages can not raise doubts, however, certain dissociation of the Indo-Iranian languages from other Indo-European would not look so distinct, if we were sufficiently known about the Phrygian and Thracian languages, which should be close to ancient Indic and ancient Iranian. So, it should be noted that the first wave, which was mentioned by Harmatta, was Indo-Aryans and later Tocharians. The Iranians formed the second wave. The ways of these waves can be specified by using both linguistic and archaeological data. Here is the thought of the linguist about the first and the second waves:

If we pass toward the South-East, we can find very interesting linguistic data for the spread and migration of Proto-Iranians and perhaps Proto-Indians to the steppes stretching north of the Caucasus, as well as for their contacts with the North-Western and the South-Eastern groups of Caucasian tribes. The earliest trace of these contacts may be represented by the Udi language eќ ‘horse’, which could only be borrowed from Indo-Iranian eќwa before the first palatalization… If we pass over to Siberia, looking for the spread toward the North-East of Proto-Iranians and Proto-Indians, we have to state that no clear linguistic traces of their direct contact with the Samoyedic people can be recognized. The reason for this phenomenon may be that a belt of tribes speaking Ket, Kott, Arin, Assan, and other relative languages separated Indo-Iranians from them. Unfortunately, apart from the Kets, the overwhelming majority of these tribes together with their languages completely disappeared [HARMATTA J., 1981: 79-80].

As we can see, the evidence is rather scanty. The archaeological data are more detailed and, in particular, can be identified with a particular wave. According to E. Kuzmina, the migration to the south of the Volga and Ural region took place at a late stage of the Zrubna culture. The main flow of Proto-Iranians came from the left bank of the Ural River along the northern and eastern shores of the Caspian Sea, where the chain of stands stretches southward near the wells, and then along the southern edge of the Karakum sands and along the river Murghab. The second wave from the West-Andronovo areas passed along the Emba River to Mangghyshlaq Peninsula, where Andronovo wave merged with the Zrubna wave. And finally, the third wave from the Ural and Western Kazakhstan moved into the northern Aral Sea region and further in the Kyzyl Kum and to Khwarezm. [KUZ'MINA E.E. 1986.: 203-204].

The broad topic of the migration of Iranians is discussed separately in sections. Cimmerians, Cimbri, Iranic Place Names

|

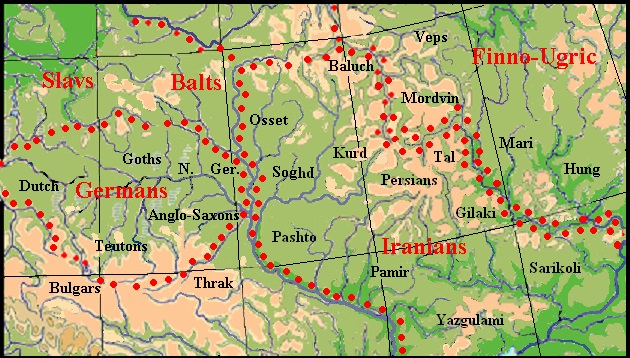

Indo-European tribes in Eastern Europe in the 2nd millennium BC..

The northern part of the right bank of the Dnieper was inhabited by the Balts and Slavs. A part of the Balts moved to the left bank of the Berezina River in the area left by the Tokharians, while the other part remained in its ancestral homeland. Thus, the initial division of the Proto-Baltic language into Western and Eastern dialects occurred. The fact that the Baltic population was concentrated here at some time is confirmed by toponymic data. Specialists emphasize that the largest proportion of Baltic hydronyms was recorded precisely in the Berezina basin [TOPOROV V.N., TRUBACHIOV O.N. 1962: 235; STRYZHAK O.S. 1981].

Slavs expanded their territory in a westerly direction. At the time of the division of the bulk of the Slavic languages from the Proto-Slavic, the Slavs already inhabited the territory between the Vistula River and the upper reaches of the Oka River south of Daugava River (see the section The Ethnogenesis of the Slavs). A part of the Slavs still lives on this territory, so it can be assumed that after settlement they never left it. However, there is evidence that before the Slavs, the Balts dwelled at least in some part of this space. They were the eastern neighbors of the Slavs for a long time.

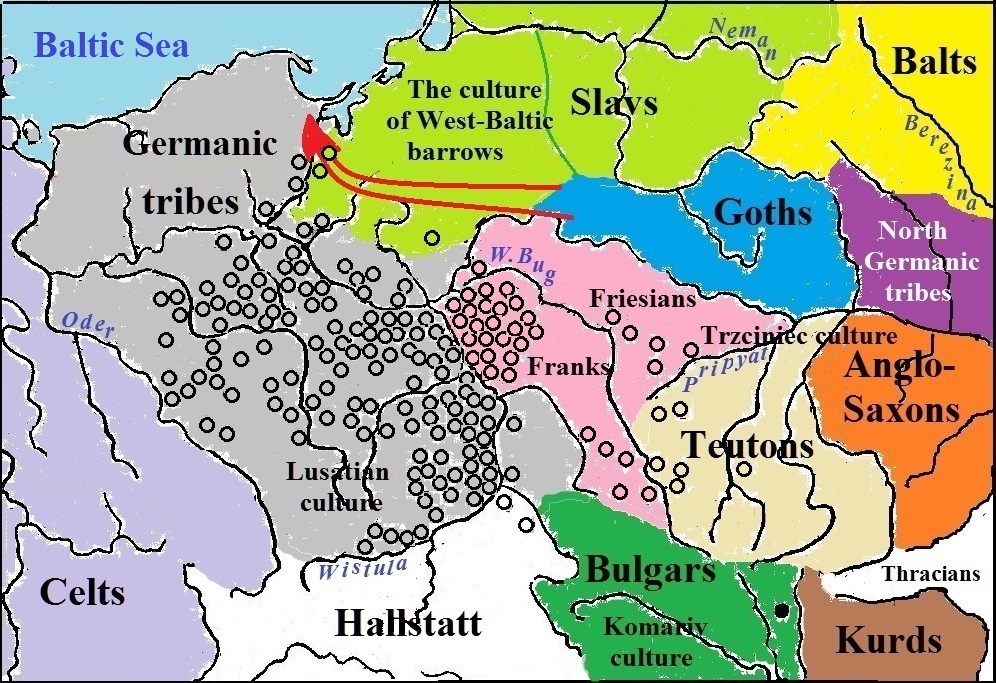

At left: The archaeological Cultures in the basins of the Dnieper, Don, and the Dniester in the XV – XII centuries. BC.

According to research made by the graphic-analytical method., Germanic tribes in the 2nd millennium BC. populated the basins of the Pripyat and Western Bug River (see Germanic Tribes in Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age and the map at left).

To the south of the East Germanic people, the Thracians dwelled on the right bank of the middle Dnieper and came here under the pressure of the Iranians from the left bank. In the Northern Black Sea region, Armenians and Phrygians could remain for some time, the bulk of whom found themselves in Asia Minor at one time. Some connections between the Sabatinovka culture in the North Pontic Region with the culture of Mycenaean Greece [CHERNIAKOV I.T. 2010: 118] confirm this hypothesis.

We associate the Germanic people with the Trzciniec culture, in which its eastern range, the so-called Sosnitska culture, dating from 1700 – 1000 BC is distinguished. [LYSENKO S.D. 2005: 60]. The Komariv culture also belongs to the Trzciniec range of cultures (TRC), the creators of which were the ancient Bulgars who lived in the upper reaches of the Dniester River south of those Germanic tribe whom we call the Teutons which inhabited Volyn. Polish scientists determine the upper limit of the Trzciniec culture on the territory of Poland by 19th st. BC. At some time, a part of the Germanic tribes (Teutons, Franks, Frisians) moved west, crossed the Vistula River, and ousted further beyond the Oder River the Celts who dwelled there. The fact that this territory was occupied by the Celts, is confirmed by Celtic place names in Poland. Having settled the territory between the Vistula and the Oder, and staying here for a long time, the Germanic people developed a Lusatian culture on the basis of the Trzciniec one. Some scientists consider this culture to be Slavic, but on the whole, their arguments in support of such a hypothesis are not convincing. Detailed criticism of the Slavic identity of the Lusatian culture referring to reputable archaeologists can be found at W. Mańczak [MAŃCZAK WITOLD. 1981], although the Polish scientist is not right about everything. Nevertheless, the main motive of his critics is supported by other scientists:

The hypothesis about the Slavic origin of the Lusatian culture is improbable already because doubtless Slavic archaeological records prove the level of a culture essentially more archaic, primitive and poor [HORÁLEK KAREL. 1983: 171].

Thus, it turns out that apart from the Germans, there is no one to recognize its creators. The boundary of the Lusatian cultures at this time was precisely defined by K.Jażdżevsky:

In the 3rd period of the Bronze Age (1300-1100 BC) the Lusatian culture manifests itself in the area which can be described as follows: its northern boundary line runs along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea from Greifswald to the mouth of the Vistula, its western border extends from Greifswald towards the Middle Elbe which is crossed somewhat north of the outlet of the Havel into the Elbe, and farther keeps to the western bank of the Elbe and advanced towards the upper course of the river capturing small parts of Old March (Altmark), Anhalt, and Saxony. The southern border can rough drown as the upper course of the Elbe (the boundary of Lusatian culture somewhat overstepped this limit to the south); it further delineates the enclave of the Lusatian area, which has advanced southward and reached as far as the basin of the Upper Morave, the Middle Vah and the Upper Nitra. Further, the border turns in the direction of the headwaters of the Oder and the Vistula until finally along the course of the Vistula does not reach the Lower Sana. Findings of the Luga culture of this period stretch east of the Vistula to Kholmshchina and Mazovia (JAŻDŻEWSKI KONRAD. 1948: 31).

|

Sites of Lusatian culture and neighboring tribes.

The map used data of Sayt ob arkheologii

Thus we can conclude that at the end of the 2nd millennium BC the majority of Germanic tribes have left the basin of the Pripyat and the territory to the east of the Vistula river was already settled by the Slavs. The settlements of the Balts were onward, they gradually expanded their territory in all directions, starting from the basin of the Berezina River. We can say quite confidently about the settlement of the Balts on the territory of Belarus during the Pre-Slavic period even till the middle of the 1st mill AD [ZVERUGO Y.G., 1990: 32]. This opinion has been formed by such competent experts as L. Niderle, V. Sedov, and others long before. We can argue about the upper chronological limit specified by Ya. Zverugo, but many of the facts, indeed, may confirm this opinion.

However, before the Balts settled the entire territory of modern-day Belorussia, the Goths and North Germanic tribes had to stay at least on a part of it for some time. As place names show, a way of the North Germanic people from the ancestral homeland in the lower Pripyat to Scandinavia passed along the Ptich River to Minsk and further towards the Western Dvina. They could not move to the west, otherwise, they would have to cut off the Goths, and the east direction was blocked by the Iranians. The Goths, moving westward obviously dissecting the Slavs, passed through East Prussia and reached the mouth of the Vistula River. This way of the Goths is fixed in the chain of place names, but no other traces of their movement or long stay in Prussia were found. They can be found only in the Welbar culture of a later time in the region of Gdansk. For details, seeAncient Teutonic, Gothic, and Frankish Place Names in Eastern Europe.

While the majority of Germanic tribes crossed the Vistula, some of them still stayed on their Urheimat. Among the remaining Germanic population was mainly the eastern tribes of the Anglo-Saxons. At some time, the Kurds appeared in their area, getting down the Desna River from their ancestral homeland to the Dnieper and crossing to its right bank. The presence of Kurds in the Anglo-Saxon area is confirmed by place names in the Kyiv and Zhytomyr Regions, decoded using the Kurdish language: Berdychev, Byshev, Devoshin, Kichkiri, Narayevka, and others. Not finding sufficient space for settlement, the Kurds moved further west and stopped in the basin of the left tributaries of the Dniester. Traces of their long presence in these places next to the Bulgars remained in numerous toponymy on the territory of the modern Khmelnytsky and Ternopil Regions. Some of its examples include the following:

v. Baznikivka, to the southwest of Kozeva in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. baz, “a falcon,” nikul, “a beak”;

v.Hermakivka (Germakivka), southeast of Borščev in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. germik, “warm place”;

v.v. Velyki and Mali Dederkaly on the outskirts of Kremenec’ in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. dederi, “a tramp,” kal, “old”;

v. Dzhulynka, to the north-east of Bershad’ in Vinnytsia Region – Kurd. colan “cradle”;

v. Kalaharivka (Kalagarivka), to the southeast of Hrymajliv in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. qal, "to kindle,” agir, “a flame”;

v. Kylkiyiv, to the north-east of Slavuty in Khmel’nyc’kyj Region – Kurd. kēlak “side”, “bank”;

v. Mikhyrinci to north-east of Volochys’k – Kurd. mexer “ruins”;

v. Mukhariv to the east of the town of Novohrad-Volynski – Kurd. mû “wool, hair”, xarû “clean, pure”;

v. Tauriv to the west of Ternopil’ – Kurd. tawer, “rock;”

v. Chepeli near Brody in the L’viv Region and northeast of Khmel’nyk in the Vinnytsia Region, and the village of Čepelivka in Khmel’nyc’kyj Region in the suburbs of Krasilov – Kurd. çepel, “dirty”;

We consider the Anglo-Saxons to be the creators of the Sosnitsa culture, and we will be consistent if we also recognize them as the creators of Lebediv culture since it was formed on the basis of the Sosnitsa. Its center was "on the area between the Pripyat and Ros" [Arkheologiya Ukrainskoy SSR. Tom 2., 1985: 445]. Obviously, its formation was influenced by that part of the Thracians who still remained between the Teterev and Ros' Rivers, when their bulk under pressure from the Anglo-Saxons already moved in search of new places. However, most of the sites of this culture are found in the triangle between the Dnieper and the Desna Rivers, although similar to them sporadically occur even till the Goryn' River [ibid, 445].

Place names witness the stay of the Anglo-Saxons on both banks of the Dnieper. On the right bank, Old English toponyms are found in the former area of the Thracians and then stretch, as well as sites of the Sosnitsa culture, to the Tiasmin River. The name of the Irpen’ River is explained on the basis of the Old English language most convincingly. This river has broad swampy flood-lands, therefore earfenn, composed of OE ear "lake" or "land" and OE fenn "marsh, mud" and translated for the name of the Irpen’ as "muddy lake" or "wetlands", suitable especially good as in ancient times the flood-plain should have been more swamped than now. OE fenn "marsh mud" could be present also in the name of the village Fenevichi near the town of Dymer in the Kyiv Region. The village is surrounded by wetlands, so the motivation for the name is well-founded. The city's name Fastov obviously comes from OE. fǽst “strong, sturdy”. OE swiera “neck”, “ravine, gorge" helps to decipher the names of the town of Skvira on the Skvirka River, rt of the Ros’, if k after s is epenthesis, ie inserted sound to give greater expression to the word. In favor of the proposed etymology says the name of the village of Krivosheino is formed from Ukrainian words meaning “curved neck” which can be a loan transcription of an older name. The village is located on this river bend.

Other examples of place names of Anglo-Saxon origin may be these:

v. Dirdyn not far from the town of Horodyshche in Cherkasy Region. – OE đirda «third»;

v. Hodorkov in Zhytomyr region – OE. fōdor "food, feed" (the Slavs had no sound f and pronounced it like hw);

t. Korsun of Shevchenko – OE cors “reed”;

v. Mircha west of the town of Dymer in Kyiv Region and v. south of the town of Malin in the Zhytomyr Region. – OE mearce “borders";

t. of Smela, the district center of Cherkassy Region. – The name of the town can have both Slavic and Anglo-Saxon origin (OE smiellan “to weave");

r. Tal, the right tribute of the Teteriv – OE *tǽl “fast” (in ge-tǽl "cheerful, lively") ;

t. Tetiev, the district center in the Kiev region – OE tǽtan “to reprove, rebuke";

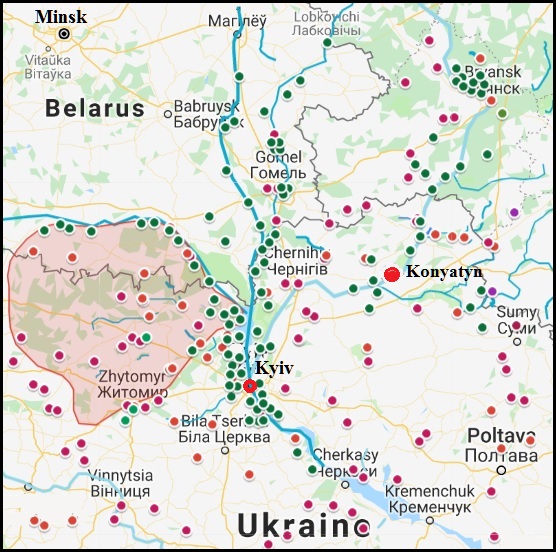

The spread of sites of Sosnitska culture

The fragment of the map onArchaeology site

The map also shows several sites of the Bondarikha culture and the village of Konyatin as the residence of the tribal elite of the Anglo-Saxons.

In the basin of the Desna River, Old English toponyms are also concentrated within the Sosnitka culture. Their especially dense group is located in the Bryansk region and they mostly belong to a later stage of its development, which may indicate that their creators came from the right bank of the Dnieper, where most of the sites belong to the early stage. The very name of Bryansk (in the chronicle Bryn') has a clear Old English origin – cf. OE bryne "fire". Such a name could be given during the time of slash-and-burn agriculture. If the Anglo-Saxons, like the Kurds earlier, used the Desna to move, but in the opposite direction, then their path to Bryansk can be marked, among others, with such toponyms:

Chernigov – OE. ciern „butter kernels”, cū "cow" (out of IE guou);

Rybotyn, a village in Korop district of Chernihiv Region – OE. rūwa "cover", tūn "town";

Fursovo, a village in Novgorod-Siverski district of Chernigov Region – OE. fyrs "furze, gorse, bramble";

Grinevo, a village in Pogar district of Bryansk Region – OE grien "sand, gravel";

Ivaytenki, Old and New, villages ib Unech district of Bruansk Region – OE. iw "wilow", wæġ (Eng. wey) "wall" (wickerwork), đennan "stretch";

Sin'kovo,a village in Zhiryatin district of Bryansk Region – OE. sinc "treasure, riches";

Malfa, a village in Vygonychi district of Bryansk Region – OE. mal "spot", fā/fāh "motley";

Many other toponyms of Anglo-Saxon origin are scattered throughout the Left-Bank Ukraine and in the adjacent regions of Russia. Most of them are located in the area of dissemination of Lebediv culture. Obviously, they were left by the second, later wave of Anglo-Saxon immigrants. Below are examples of the most transparent interpretation of some toponyms:

v. Byrlovka in Drabiv district of Cherkassy Region. – OE byrla „body”;

t. Dykanka in Poltava Region – OE đicce “tick”, anga „thorn, edge”;

the city of Homel in Belorussia – OE humele „bryonia”, hymele "hop, hops";

t. Ichnia in Chernihiv Region – OE eacnian „to add”;

vv. Ivot to the east of the town Novhorod-Siverski and in the north of Bryansk Region in Russia, rivers Ivotka, Ivotok – OE ea "river", wœt "fury";

r. Kleven', pt. of the Seym – OE cliewen “a clew”;

v. Konyatyn in Sosnytsia district of Chernihiv Region – Gmc. *kunja "kin", "noble origin" and OE tūn "town".

r. Nerussa, lt. of the Desna – OE neru “nourishment”, usse „our”;

r. Resseta rt of the Zhizdra, lt of the Oka – OE rǽs "running" (from rǽsan "to race, hurry") or rīsan "to rise" and seađ "spring, source";

t. Romodan in Myrhorod district of Poltava Region – OE rūma „space”, OE dān „humid, humid place”;

t. Romny in Sumy Region – OE romian “to seek, aim”.

t. Senkiv in Poltava district – OE sencan “to dip, sink”.

r. Svessa, lt. of the Ivotka, lt. of the Desna, the town of Svessa in Sumy district – OE swǽs “peculiar, pleasant, beloved”.

r. Seym, lt. of the Desna – OE seam "side, seam".

r. Smiach, rt. of the Snov, rt. of the Desna – OE smieć “smoke, steam”.

t. Sugia on r. Sugia, lt Psel – OE sugga „sparrow”;

r. Ul, lt. of the Sev, lt. of Nerussa, lt. of the Desna – OE ule “owl”.

r. Volfa, lt. of the Seym – OE wulf “wolf”.

r. Vytebet', lt of the Zhyzdra, rt of the Oka – OE wid(e) "wide", bedd "bed, river-bed".

It is significant that place nanes of English origin waere recorded not only in the territory of the Lebediv culture, which was separated from the Bondarikha by the Sula River, but also further to the Vorskla. Obviously, the Anglo-Saxons supplanted the creators of the latter, which were obviously Mordovian tribes, with whom they, however, remained in certain contacts (for more details, see the section"The Expansion of the Finno-Ugric Peoples"). The Sula River has many different explanations [VASMER M., 1971: 799-800; MENGES K.H. 1979: 131], incuding Mok s'ula, Erz s'ulo "a gut" but OE solu "a pool, puddle, slop" suits best of all. The Anglo-Saxons, or perhaps only a part of them, remained on the left Bank of Ukraine until the Migration Period. This is evidenced by some Scythian realities, the epigraphic of the Northern Black Sea region and historical events (see the Alans-Angles-Saxons

For some reason, the Anglo-Saxons passed on the left bank of the Dnieper is difficult to say. One of the reasons could be the relative overpopulation caused by the depletion of the natural resources of the area, but the Anglo-Saxons could leave their ancestral homeland forcing invasions of tribes speaking in other languages. The emergence of the Kurds might have played some role, but the pressure of the Balts who moved to the right bank of the Pripyat River was more likely. The presence of the Balts to the south of the Pripyat is indicated by the interpretation of hydronymic data, made by V.Toporov and O.Trubachev, who considered the appearance of Balts there as natural events:

The presence of Baltic elements on both sides of the Pripyat looks doubtful only under the condition that the Pripyat was an insurmountable border, as it is usually considered in the literature [TOPOROV V.N., TRUBACHEV O.N., 1962: 233].

The Archaeological Cultures in the Basins of the Dnieper, Don, and Dniester in the XV – VIII Centuries. BC. and paths of the migration of their creatirs

As it was noted, Berezina divided the Balts into two groups – the eastern and western dialects. It is logical to assume that Lithuanian, Latvian (Latgalian), Selon, Zemgale, and Kuronian developed from the eastern dialect as they are less conservative than the languages developed from the Western dialect (Prussian and Yatviazh). At the same time, of all the Baltic languages, Latvian is less archaic. Obviously, the speakers of a more archaic Lithuanian language all the time remained near the ancestral home of the Balts, as was pointed out by a well-known Bulgarian linguist [GEORGIEV Vl., 1958: 247]. An external factor of such features of the Baltic languages may be the different intensities of the Baltic-Finnish contacts [MAŽIULIS V., 1973: 28-29].

The northern-east and eastern boundaries of Baltic settlement to the moment of the early Iron Age (8-7 ages B.C.) were defined by V.V.Sedov. In his opinion, the boundary ran along the course of the West Dvina (Daugava River) eastward to the upper Lovat’ River and to the sources of the Dnepr, then to the south-east, crossed the river Oka near the mouth of its tributary the Ugra River and further lay along the watershed between the Oka and the Don rivers [SEDOV V.V., 1990-2: 90]. Sedov believes that Balts occupied areas from the south-eastern coast of the Baltic Sea up to the upper Oka and the middle Dnepr, producing here three tribe groups – western (the tribe of West-Baltic barrows), median (the tribe of the shaded claywares), and the Dnepr group (the tribes of the Dnepr-Dvina, the upper Oka and the Yukhnov cultures) [ibid: 90]. However the culture of the West-Baltic kurgans, in spite of V. Sedov, was created not by Balts, but by Slavs, who passed from their Urheimat to the left bank of the Neman River and settled the shore of the Baltic Sea from the Vistula till the Neman and Venta River. In course of time, the Baltes crossed the Neman and were mixed with the local Slavic population what was resulted in some ethnic groups of the Yotvingians. Some scientists believe that once the tribes of the Yotvingians and Galindians formed a part of the Proto-Slavic dialect area [BIRNBAUM H.,1993: 14]. In this regard, it can be assumed that the ancestors of the Prussians and Yotvingians moved closer to the shores of the Baltic, where they become known already in historical times and where they are least affected by Finnish languages. Archaeological data are confirmed by the toponymy:

As a whole, the northern and eastern boundaries of the Baltic tribes of the early Iron Age in the main coincide with the boundary separating the Baltic and Finno-Ugric toponymies and hydronyms. This boundary ran from the Gulf of Riga to the upper reaches of the Western Dvina and the Volga. Turning further to the south, it is cut off Riverlands of the Moskva-river from the basin of the Volga river and the upper reaches of the Oka river, then along the watershed of the Oka and the upper reaches of the Don came to the steppe [TRET'YAKOV P.N., 1982: 54-55].

Taking into account the archaeological and toponymic data, it can be assumed that part of the eastern Balts, moving from the Dnieper and Berezina rivers to the north, moved to the right bank of the Western Dvina, where they created the Dnieper-Dvina culture, and later, moving along the Western Dvina to the North West, reached the sea and became, over time, the core of the Latvian ethnic group. Another group of eastern Balts moved eastward, crossing the Dnieper and displacing the Iranians from the Desna basin. This could be the reason for the movement of the Kurds to the Anglo-Saxon area.

Traces of the Balts are found in the dialects and place names of Central Russia [GORDIEYEV F.I. 1990: 62, TOPOROV V.N., 1973-2]. They can be found also in the Permian and Finno-Volga languages (cf. Komi Zyr. yuavny, Udm. yuany "to ask" – Let. jautät “to ask”, Mari kaim "a resident of the nearby" – Let. kaiminš “neighbor”). The Balto-Finnic language communication was studied by B. Serebrennikov, G. Knabe, F. Gordieyev, A. Joki. A lot of the Baltic-Mordvinic and Baltic-Mari lexical correspondences gave in one of his works Khalikov [KHALIKOV A.Kh., 1990: 57]. In addition, contacts between some Baltic ethnic groups and the Mordvins are confirmed by Mordvinic mythology. For example, the name and image of the Mordvinic Thunder-god Purgine-paz, the son-in-low of god-demiurge Nishke arose under the influence of Baltic mythology (Lith. Perkúnas, Let. Pérkóns, Pr. *Perkunas). The image of the god of thunder, lightning, and rain with a similar name has an origin in Indo-European mythology, but the importance for our research is the existence of such a mythological figure by the Thracians, whose name we know in Greek transcription Περκων. The names of the gods in other Indo-European peoples of the same origin (Slav. Perun, OInd. Parjanya, Hit. Pirva) are somewhat far [IVANOV V.V., TOPOROV V.N., 1991. MFW. Volume 2, 303-304] Hence, the area of worship of god Perkonu/Perginu covered the Baltic, Thracian (Dacian-Thracian), and Mordvinic ethnic areas which had to be located somewhere in adjacency. Consequently, the area of worship of the god Perkon/Pergin encompassed the Baltic, Thracian (Daco-Thracian), and Mordovian ethnic areas, which should have been somewhere in the neighborhood. It should also be added that the ancient Germans, the area of settlements which have been near the Bulgars, could borrow the image of one of their gods from the Bulgars, as the Chuvashes have still now a whole pantheon of gods with the word tură "god" in the second part of their name reminiscent of the name of the Scandinavian god Thor. The explanation of the Chuvash word for the name of God is a derivative of Turk. teŋgri is doubtful for phonological reasons. The Chuvash god-demiurge Sulti tură or the goblin Hurt-Surt could be reflected in the Scandinavian fire giant Surt, who came from somewhere in the south, after a battle with local gods burn the whole world. A. Khalikov also compares the Chuvash family spirit named ierekh/irikh with the family spirit of the Latvians (gars/geris). He also cites several Baltic-Chuvash lexical correspondences (KHALIKOV J. 1990, 57). Thus, the Balts would have to have some contact also with the ancient Bulgars at a time when they inhabited the right bank of the Dnieper.

The Balts, which remained in their historic homeland, correspond to the range of culture of the Hatched-Ware Culture (HWC). The Dnieper-Dvinsk culture and HWC are very close to each other. The only difference is in the shapes and proportions of the dishes. (ZVERUGO Ya.G. 1990, 32). The Hatched-Ware Culture existed until the middle of the 1st millennium BC. It was disseminated in Eastern Lithuania and Central Belarus, it belonged to the ancestors of modern Lithuanians. [VOLKAITE-KULIKAUSKIENE R R, 1990: 15]. Its carriers, moving from the right bank of the Berezina along the Daugava River, also reached the coast of the Baltic Sea. Here, the Baltic tribes of the Curonians left their group burial grounds, and on the lower Neman, the Skalvs did. Between the right tributaries of the Neman, the Dubisa, and the Yura rivers, there were settlements of the Samogitians and the Zemgals inhabited the north of Lithuania in the headwaters of the Musha River. [ibid: 14].

At the beginning of the 1st mill. BC tribes of the Dnieper-Dvinsk culture from Smolensk Dnieper began to move to the western regions of the Volga-Oka watershed [SEDOV V.V., 1990-2: 92]. This can be confirmed by many facts. B.A.Serebrennikov pays attention to the data of the Kyiv Chronicle, according to it, one of the ancient Lithuanian tribes, the Galindians, occupied the basin of the river Protva, lt of the Oka. He writes that M.Vasmer drowned the northern-east boundary of the Baltic place-names to the Tsna River[SEREBRENNIKOV B.A., 1965]. V. Toporov places the most eastern wave of the Baltic-speaking population along with the Oka [TOPOROV V.N., 1983: 49]. On the other hand, there is evidence in favor of the presence of the Balts in more southern areas. Toporov and Trubachev, examining the hydronymy of the Upper Dnieper, came to the conclusion:

The undoubted presence of Balts on the Seym River has been proved to be true… by the whole congestion Baltic hydronymic in quantities not less than two tens in this area [TOPOROV V.N., TRUBACHIOV O.N. 1962: 231].

As examples, these scholars bring such names of rivers: Obesta (Abesta, Obsta) Kubr (Kubar, Kubera) Vopka, Morocha, Molch, Vabla, Terepsha, Lepta, Lokot’, Raten, Rat’, Tureyka, Zhelen’, Uspert, Rekhta, Zhadinka, etc. However, as we have seen, there are many place names of Anglo-Saxon origin in the Seym basin. The Balts brought with them the Milograd culture, which also occupied some part of the region of the Sosnitsa culture, but according to L. D. Pobol, these cultures do not have genetic connections between themselves [POBOL L.D. 1983: 16]. Obviously, certain differences between them are explained by the different ethnicity of their creators, and the common elements are due to cultural influences and borrowings. Everything suggests that the Balts came to the Seym River later than the Anglo-Saxons, pushing them further south. Obviously, this happened already in the Scythian time.

Apparently, it was established among specialists that hydronyms belong to more ancient times compared to oikonyms and therefore limited their research to hydronymy, without attaching great importance to the names of settlements in the study areas. If we study the oikonyms of Eastern Europe more closely, then we can find traces of the Balts all over Ukraine and even in the Balkans and in the Pre-Caucasus. The results of the search for Baltic toponymy outside the modern ethnic territories of the Balts were put on a Google Map (see below).

Baltic place names outside ethnic territories

The map shows that the Baltic toponymy is widely disseminated over a wide area, which is confirmed by various areas of knowledge. In particular, the presence of Balts beyond the Danube is indicated by the Baltimism in the languages of the local population. Special Balto-Thracian contacts were noted by V.N. Toporov, J. Nalepa, and other linguists. Applying the method of quantitative evaluation of common lexical correspondences, I. Duridanov investigated the connections of the Thracian and related Dacian languages with the Baltic and Slavic languages. Comparing the results, he came to the following conclusion:

…in prehistoric times – about the 3rd millennium BC – the Baltic, Dacian, and Thracian tribes inhabited neighboring regions, and the first dwelled next to the Dacians and Thracians. Whether the Balts bordered on the other side with the Illyrians is left, in my opinion, in question [DURIDANOV IVAN., 1969: 100].

Of course, there is no reason to speak about the neighborhood of the Balts and the Daco-Thracians in the 3rd mill BC, but the fact of the neighborhood is important in itself. No special connection between the Slavic languages with Thracian and Dacian the Bulgarian linguist didn't find, except for small amounts of possible common Dacian-Baltic-Slavic and Thracian-Baltic-Slavic lexical correspondences, as he noted in his conclusions, so there is no reason to believe that settlements of the Slavs were located somewhere near the Daco-Thracian area. A. Desnitsky reaffirms the conclusion of I. Duridanov. Finding the common features of Albanian and Baltic (including the disappearance of the category neuter), she argues that most of these features are absent in the Germanic and Slavic languages [DESNITSKAJA A.V., 1984: 224].

Thus, some parts of the Balts should have moved far to the south, but at the same time, they lost contact with their relatives in the north and dissolved among the local population. Being in the steppes of Ukraine, they should have had contacts with the Scythians-Bulgars, however, the most ancient Turkic (namely, Bulgarian) influences on the Slavic languages have no correspondences in the modern Baltic languages [MENGES KARL H., 1990].

There are very little data to search for traces of the Thracians after they went in search of new places, being driven out by the Anglo-Saxons. It can be assumed that a part of the Thracians stopped in the basin of the Southern Bug and remained there until approximately the 8th c. BC. The basis for this assumption is the accumulation of settlements around the city of Uman ethnically unidentified Biloğrudiv culture that existed in the XI-IX cen. BC. According to Terenozhkin, the main and most studied cluster of the sites of Biloğrudiv culture is located in an almost solid array within a radius of 40 km around Uman [TERENOZHKIN A.I., 1961: 6]. Some of these sites are located on the banks of the Yatran River, which name may be of Thracian origin. The total area of the Biloğrudiv tribes is outlined by A.Terenozhkinas follows:

…their settlements can be met before the steppe zone in the south, to the Dnieper River in the east, to the area of the forest and the right-bank tributaries of the Pripyat in the north and to the Dniester in the west [ibid: 213-214].

A.Terenozhkin, which studied the Bilogrud and the Chornolis cultures in detail, believes that the Bilogrudov clans led a quiet, peaceful life. This is evidenced by the absence of hillforts and by the topographic peculiarity of the settlements. In his opinion, toward the beginning of the Scythian period, the Bilogrudiv tribes abandoned the Uman’ area for unknown reasons and probably moved to the basin of the Dniester [ibid: 12]. One might conjecture the Bilogrudiv people have left further to the Balkans. Such assumptions can be confirmed by certain cultural influences of the Bilogrudiv culture on the Thracian Halstatt culture in Moldova:

… the burnished earthenware with carved and impressed decoration appears for the first time in the Bilogrudiv and the Chornolis cultures whence it only could to penetrate beyond the Dniester to Moldova, in the Thracian Halstatt culture at the end of the 8th or at the beginning of the 7th centuries BC. Together with eastern ornament, scoops with ledges on the handle, bowls with cylindrical necks and spherical bodies, and even simple vessels of tulip shapes with punctures on the rim and split by a roller, the all typical for the culture of the Ukrainian forest-steppes, were extended in Moldova where can-form vessels were prevalent [ibid: 216].

However, the assumption made contradicts the opinion about the time of the formation of the Thracian ethnocultural community, supported by the majority of researchers. In general, it is believed that this process should be attributed to the beginning of the early Iron Age:

The formation of the Thracian ethnocultural community is referred by most researchers to the beginning of the Early Iron Age. The peoples of the previous period, in particular the creators of the native Noa and Koslodzheni cultures closely associated with the tribes of the northern Black Sea Region, are considered by Romanian scientists to be included in the Thracian community, but being not the Thracians. The sharp change of cultures in 11-12th centuries. BC, which the researchers observed in the Carpathian-Danube region, is a convincing argument in favor of this conclusion, indicating the emergence of a new population here. Just this alien population is considered to be the nucleus of the northern Thracians, assimilating local tribes [MELUKOVA A.I. 1979: 14].

In this regard, it cannot be excepted out that the Balts were the creators of Bilogrudiv culture. Just the name of the Yatran River and other toponyms near Uman, such as Apolyanka, Gorezhenivka, Grodzeve, Lehedzine, Shelpakhivka may have a Baltic origin. Then the change of cultures in the Carpatho-Danube region of the 11th and 12th cen. can be associated with the arrival there of Thracians or Phrygians and Armenians who migrated from the Northern Black Sea region, where at about the same time there was a change of cultures – Belozerska culture (12-10 centuries BC) appeared at the place of Sabatinovka one.

Whatever it was, the Balts could coexist with the Thracians and have language contacts with them.

The migration of Balts of a later time in the section Ancient Balts Outside Ethnic Territories

Later migrations of the Anglo-Saxons are covered in the section Anglo-Saxons in East Europe