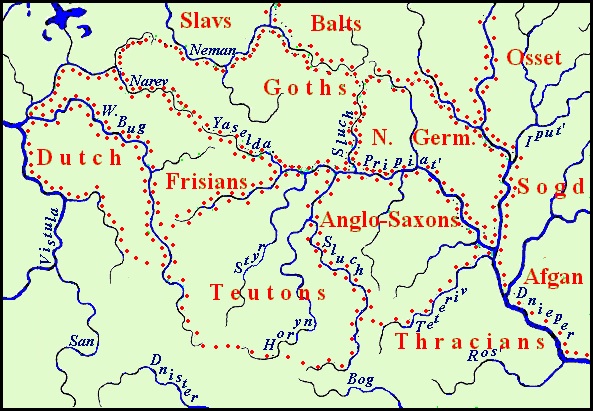

The forefathers of Germanic People in Eastern Europe according to toponymy data

The homeland of the Germanic peoples, that is, the territory which on the Proto-Germanic language was formed, was defined by the graphic-analytical Method on an ethno-producing area west of the Sluch River (the left tributary of the Pripyat) between the Neman, Narev, and Yaselda Rivers. Later, the Germanic peoples settled on both sides of the Pripyat (see the section "Germanic Tribes in the Eastern Europe at the Bronze Age )". The disposition of the areas of individual primary Germanic tribes (see the map below) is confirmed by the toponymy remaining there by them, deciphered by the ancient languages of their modern descendants.

The topic of Germanic toponymy is discussed in more detail in the following sections:

Ancient Teutonic, Gothic, and Frankish Place Names in Eastern Europe.

North Germanic Place Names in Belorus, Baltic States, and Russia.

In this section this topic is limited to the German toponymy on the ancestral homeland of the individual primary Germanic tribes.

The disposition of the areas of individual primary Germanic tribes in II mill BC.

The ethno-producing area, located between the Western Bug and Sluch Rivers, south from the Upper Pripyat, that is, the historical region Volyn (at present Volins’ka oblast’, or Volin Region) was inhabited by the ancient Germans (Teutons) in the 2nd mill BC. It was here that the deep basis of the modern German language was laid. After the departure of the bulk of the Germans to the west, a Slavs tribe settled in the area, the dialect of which later developed into Czech, and when they largely left this area, it was occupied by new Slavic settlers who, in historical times, became known as the Dulebes or Dudlebes. The name of this tribe has been preserved in several place names of Western Ukraine and the Czech Republic, and according to some scholars this ethnonym derives from W.G. Deudo and laifs (EDU and EDR).

The first part of the group’s name means “Teutons”, from which the eponymous designation for modern Germans (Deutsch) derives; the second part means “the rest” (Got. laiba, O.Eng. làf). Thus the word Dulebs may be explained as “the remnants of the Teutons”, what gives grounds to say that not all Germans left Volyn when they moved to Central Europe, and the name of the inhabitants of this region remained the there for a long time. It can also be recalled that there are regions of Wollin/Volin on the new settlements both the Teutons and the Czechs.

Teutonic place names

The most persuasive evidence of a Teutonic settlement in Volhynia comes from the mysterious name of the village Velbovno in Rivno Region, located adjacent to Ostroh on the right bank of the Horyn’ River. The name consists of two ancient Germanic words: O.U.G. welb-en, “to erect the arch,” and ovan, "furnace.” An arching furnace made of stone is a rather commonplace item but nevertheless may have served a special purpose. In this place along the right bank of the Horyn’, impassable bogs span many kilometers. As such, the furnace may have been used to smelt iron from marsh ore. The town of Neteshin is located near to Velbovne. Its name may also have Germanic origins. For the area with metallurgical furnaces, the second part of the name can be connected with O.H.G. asca "ashes" (Ger. Asche). Accordingly, for the first part of the word, you should look for something logically related to the second one. Old Icelandic hnjođa "to forge" suits well. In the German language is present a derivative from the disappeared relative word Niete "a rivet" [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 504]. The bloomery produced not pure iron, but a porous mass with impurities of sulfur, phosphorus, and other metals and slag. To produce iron, this bloom must be re-forged, when the impurities were separated as ash [ZVORYKIN А.А. a.o. 1962: 68]. Thus, there was a specialization – the bloom was produced in Velbovne, and it was converted to more or less pure iron in Neteshin.

We now look at several other examples of place names which have no compelling definition by means of the Slavic languages, but which can be etymologized on the basis of German:

The village of Farinky, east of Kamin' Kashirsky – Ger Fähre from *fahreja "to transfer”.

The village of Fusiv in Sokal district, Lviv Region – Ger Fuß, MHG vouz “foot”.

The town of Kiverci – Ger. Kiefer, M.U.G. kiver, "jaw, chin".

The city of Kovel- Ger. Kabel “fatr, lot”, MHG. kavel-en – "to draw lots".

The village of Nevel, southwest of the Belarusian city Pinsk – Ger. Nebel, "fog".

Lake Nobel and the village of Nobel, located west of Zarične in Rivno Region on a peninsula of the lake – Ger. Nabel, O.U.G. nabalo, “navel”.

The village of Pare on the Prastyr Strait – Ger. Fähre “ferry”.

The town of Radekhiv, Lviv Region – Ger Rad “wheel”, Echse “axle”.

The town of Radyviliv, Rivne Region – Ger Rad “wheel”, Eibe, Ger īw- “willow”.

The village of Rastov, west of Turijs’k – O.U.G. rasta, "stay".

The village of Reklynets in Sokal district, Lviv Region – Ger. Rekel “a big he-dog”.

The Styr River, the tributary of the Pripjat’ – Ger. Stör, O.U.G. stür(e), "sturgeon”.

The Strypa River, the tributary of the Dnister, which spring lies on the border of the Teuton area – M.N.G. strīpe “a stripe”. However the name can have Anglo-Saxon origin.

The village of Tsehiv in Horokhiv district, Volyn Region – MHG zæh(e) "viscous, tough".

The village of Tsuman, to east of Kivertsi – Ger. zu Mann “to a man”.

The Tsyr River and the village of Tsyr – Ger. Zier, "ornament,” and O.U.G. zieri, "good.”

These examples list of names of Teutonic origin in Volyn may not be exhaustive, but there are in the northern part of the area, some place names could also have a Frankish origin. We have agreed to call the ancestors of the Dutch as the Franks, who, together with the Frisians occupied the westernmost area of the entire German territory bounded by San and the Vistula River in the west, in the north of the Niemen, Yaselda in the northeast and the upper Pripyat River in the southeast. There is on the border of this area with the Teutonic one near Lakes Shatski an accumulation of names, which can have both Teutonic or Frankish origin. The very name of the lakes is best deciphered with the help of the German languages (OHG scaz, "money, cattle", Ger. Schatz "treasure", Dt. schat "the same"). We can also speak of the Teutonic origin of the names of the village of Pulemets and Lake Pulemetske. They can be deciphered as "the full measure of grain" (Ger. volle Metze, OHG fulle mezza – EWDS). A fancy name of another lake Lyutsemer can be understood as the "little sea" (Ger. lütt, lütz, OHG. luzzil "little", mer, Ger. Meer "sea"). Words similar to the mentioned exist sometimes in other Germanic languages, but here is present transition of Germanic t in z), characteristic only for the High German language. At the same time the name of Lake Svityaz stands better to the Dutch language, as GMC *hweits "white" corresponds better Dt. wit and jyst its pre-form *hwit could naturally transfotm to Svityaz in the Slavic languages (GMC. -ing, -ung corresponds always Slav -iaz'). For OHG. (h)wīz "white", it seems unreal.

Frankish place names

In indicated above habitat obviously the Western Bug River shared the Franks and Frisians. A Frisian dictionary of a large amount was avsent for services, so we will restrict the search of names that can have a Frankish origin using the Dutch language. While we can talk about such possible Frankish place names:

Brok, a town in Ostrów Mazowiecka County, Masovian Voivodeship and a village in the administrative district of Gmina Wysokie Mazowieckie, within Wysokie Mazowieckie County, Podlaskie Voivodeship – Dt. broek, M.Dt. brōk “humid lowland”;

Western Bug, rt of the Vstula River – М. Фасмер рассматривает возможность германского происхождения названия Западного Буга, но нидерландских слов не приводит. Между тем, ср.-нид. bugen (нид. buigen) «гнуть, сгинать» подходит лучше всего (река Западный Буг очень извилиста);

Garwolin, a village in Masovian Voivodeship – Dt. garwe, garf “sheaf”, lijn “flax”;

Kobryn, a town in Belarus – Dt. kobber “he-pigeon”;

Kodeń, a village on the banks of the Western Bug River in Poland – Dt. kodde “sack, knot”;

Kujawy, a village in Masovian Voivodeship – Dt. kuif “a crest”;

Malaryta, a town in Brest Reion – the town could be named Mala Rita (Small Rita) as it is located on a small river Rita, whose name can be connected with ODt rith "flood" (OE riđ "stream").

Wagan, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Tłuszcz, within Wołomin County, Masovian Voivodeship – Dt. wagen “a car”;

Worsy, a village in Lublin Voivodeship – Dt. vors “frog”;

Germanic place names in Eastern Europe

Germanic place names in Eastern Europe

On the map, settlements are indicated by asterisks.

Teutonic place names – red. The Urheimat of the Teutons tinted by red

Frankish place names – blue. The ancestral home of the Franks and Frisians tinted by blue

Gothic place names – green. The ancestral home of the Goths tinted by green

North Germanic place names – brown. The ancestral home of the North Germanic people tited by brown

Anglo-Saxon place names – orange. The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons tited by yellow

Hydronyms are indicated by blue circles and lines.

North Germanic and Anglo-Saxon place names are shown only partially, only to indicate the directions of migrations.

Gothic place names

The area of the formation of the Gothic language because of the scarcity of available lexicon was localized only tentatively Shchara on both sides of the Shchara River, left tributary of the Niemen River, ie where there was the common Urheimat of all Germanic people. The name of this river should be considered Paleo-European substrate, traces of which can be found in some Germanic languages such as Eng. shore, Ger. Schaar "area of the sea, where you can wade." Nevertheless, local place names gives grounds to assert that the Gothic language began to form here. When their deciphering F. Holthausen's (Gothic Dictionary Holthausen, 1934) was used and partly Dictionary of the Icelandic Language as the closest to the Gothic. The following are examples of possible urban place names in Belarus:

Abrova, a village in Ivatsevich districk of Brest Region – Got. *abr-s "strong, stormy".

Alba, a village in Brest Region, Belarus – Got.*alb-s "a demon".

Bastyn', a village ib Lunenets district of Brest Region – the all modern Germanic languages have thw word bast "bast, the inner bark of the lime-tree" (Old Norse, Dt. bast, OE. bæst, Ger. Bast). Undoubtedly, this word was present in the Gothic language, but not preserved in written sources referring to the specific of values.

Lida, a town in Grodno Region, Belarus – Got. liudan "to grow", lita "transposition".

Rumliovo, a forest park in the city of Grodno – Got.rūm "room, space", lēw "a case".

Trabovychy, a village in Lakhovychy districkt of Brest Region – Got *draibjan "to drive".

Vangi, a village в Grodno Region, Belarus – Old Norse vang-r "a garden, green home-field".

Zelva, the center of district in Grodno Region – Got. silba, Old Fr. selva "self".

There are on the Urheimat of the Goths a few place names, which could be deciphered by other Germanic languages (Fasty, Gresk, Narev, Rekliovtsy), the Gothic language has or had silmilar word, therefore it is difficult to judge about their origin.

Nirth Germanic place names

The ancestral home (Urheimat) of the Northern Germans defined by graphical-analytical method, was located in ethno-producing area limited by the Dnieper, Pripyat, Berezina, and Sluch (lt of the Pripyat) Rivers. It is here and near, a small cluster of names that can have North German origin has been found. Explanation of clearly not Slavic names was made mainly by means of the dictionary of Icelandic language, which is considered as "the Classical Language of Scandinavian race" (An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Preface. The etymological dictionaries of the English and German languages (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974, KLUGE F. 1989) were used to clarify the meanings of words and of phonological patterns of the Germanic languages as also Online Ethymologic Dictionary.

To date, we found about a hundred of names of possible North Germanic origin. Full list is constantly updated with new data, made decryption are clarified, detected errors are removed, but in general such a large set could not be random. Following are some examples of decipherments of names by means of the Old Norse language:

Berkav, a village in Homel Region – Old Norse björk "birch".

Bonda, a hamlet in Vishnev comunity of Smorgon' district Of Grodno Region – Old Norse bóndi "a tiller of the ground" bónda-fólk "tillers".

Bryniow, a village in Gomel Region, Belarus – Old Norse brynja "a coat of mail".

Dowsk, a village in Gomel Region, Belarus – Old Norse döv, Nor. døve "deaf".

Drybin, a village in Mogilev Region, Belarus – Old Norse drīfa, "to drive".

Gawli, a village in Gomel Region, Belarus – Old Norse gafl "gable-end', Sw gavel, "end", Norw gavl "gable".

Gerviaty, a settlement, Astravets district, Grodno Region – Old Norse görva, gerva "gear, apparel", tá "a path, walk".

Gomel (Homyel), a city in Belarus – OLd Norse humli, Sw humle, OE hymele ”hop plant”.

Minsk (originelly Mensk), the capital of Belorus – Old Norse mennska "humanity", mennskr "human".

Nevel, (obviously initially difficult to pronounce Nebl), a lake on the border between Belarus and Russia – Old Norse nifl, Ger Nebel "mist, fog".

Ordovo, a lake near the lake Nevel– Sw ort "ide" (a kind of fish). Similar name of the fish is yet not found in Icelandic.

Randowka, a village in Gomel Region, Belarus – Old Norse rønd «rim, border», Sw rand «border, side».

Rekta, a village in Mogilev Region, Belarus – Old Norse rækta "to take care of, cultivate".

Skepnia, a village in Gomel Region, Belarus – Old Norse skepna "a shape, form".

Smargon', a city in Grodno Region – Old Norse smar "small", göng "lobby".

Svedskae, a village in Gomel Region, Belarus – Old Norse svæđi "an open place".

Svir', a village and a lake in Miadel district of Minsk Region – Old Norse svíri "the neck".

Shvakshty, a village and a lake in Miadel district of Minsk Region – Old Norse skvakka "o give a sound".

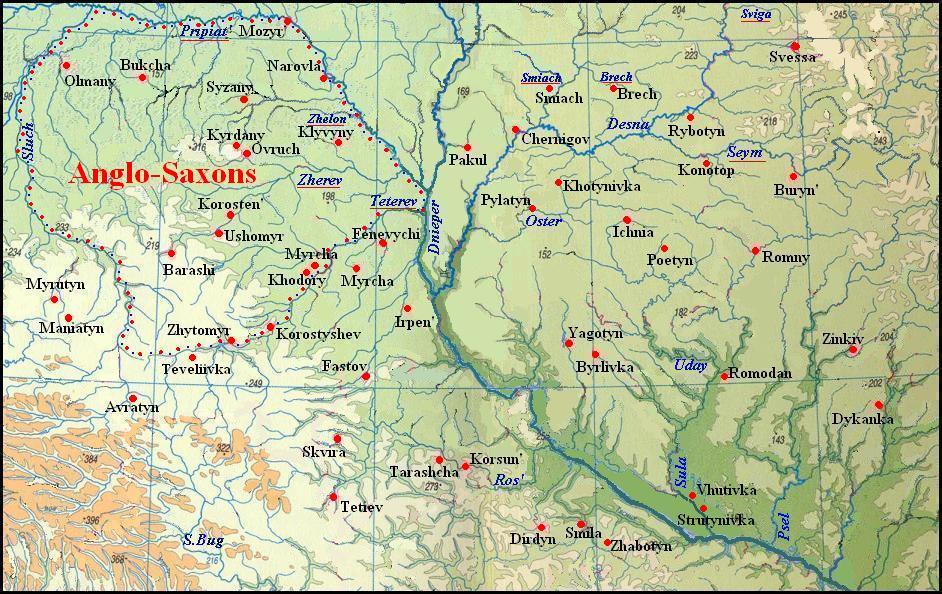

Anglo-Saxon place names

The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons was localized in the ethno-producing area between the Sluch, Pripyat, and Teteriv Rivers. This area was at first populated by the ancient Italics (forebears of the Latinians, Oscans, and Umbrians), then by the Anglo-Saxons, and subsequently by the ancestors of the Slovaks. In more recent history, this space was inhabited by the Slavic tribe of Drevljan, whose capital was the fabled town of Iskorosten. Scribes have clearly tried "to slavicize" the name of this town, now called to simply as Korosten, which no doubt comes close to the name used at ancient times.

The town is located above the Usha River, which meanders along granite banks. Here the English language affords us an opportunity to etymologize the name of the town, using O.E. stān, “stone, rock” and the Cornish care, “rocky ash” presented in the place name Care-brōk (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 43). The root care can also be found in the name of the town of Korostishev, located on the Teteriv’s rocky left bank. If the second part of this toponym derives from O.Eng. sticca, “stick, staff”, the place name can be taken as a whole to mean “ashen stick”. This, at first glance, a convincing explanation of names Korosten and Korostishev is doubtful. The fact, that the mountain ash (Fraxinus ornus) does not grow in this locality, does not mean much, because the common ash tree is very spread here and the transfer of names of plant species from one to another is a known phenomenon. Much more objection has the explanation by using the word care, which can have a Celtic origin (Ibid).

The name of another town is connected to rocks as well: this is Ovruch, located in the Slovečan-Ovruč Hills on the upper left bank of the Norin’ River. Eng. of rock may be explained as “on rocks” as well as “near rocks,” or "rocky”.

At left: Anglo-Saxon place names on the ancestral homeland of the Anglo-Saxons (its borders are marked with red dots) and out of it on new places of settlements.

As a whole, we can etymologize nearly forty local place names by means of the English language. Some of them are listed below:

Barashi, a village in Yemelchine district of Zhitomyr Region – OE bǽr “abandoned, bare”, ǽsс “ash-tree”.

Fenevychi, a village at the bank of the upper Teteriv River – OE fenn "swamp", wīc “house, village”.

Khodory, Khodorkiv, and Khodurkiv, villages in Zhitomyr Region – OE. hador “vigorous, brisk".

Kyrdany, a village near Ovruch – OE cyrten "beautiful”.

Latovnia, a river, right tributary (rt.) of the Ten’ka, rt of the Tnia, rt of the Sluch – OE latteow "leader”.

Mozyr’, a city, Belarus – OE. Maser-feld to N.Gmc. mosurr "maple" (AEW).

Narovlia/ the town on the right bank of the Pripjat’ River – OE nearu “narrow” and wæl “pool, source”.

Olmany, a village in Belarus, southeast of the town of Stolin – OE oll “to insult, abuse,”mann, manna “a man” man “fault, sin”.

Prypiat’, a river, rt of the Dnieper – OE frio "free", frea “lord, god”, pytt “a hole, pool, source”.

Rikhta, a river, lt of the Trostianycia, rt of the Irsha – OE riht, ryht “right, direct”.

Syzany, a village south of the Homel’ Region in Belarus – OE. sessian “to grow quiet”.

Zhelon’, a river, rt of the Low Prypiat’ – OE scielian “to part”.

Zherev, a river, lt of the Už, and r Žereva, lt of the Teteriv, rt of the Dnieper – O.Eng. gierwan "to boil” or "to decorate” (both meanings suit the toponyms, depending on the character of the respective river).

The Anglo-Saxons migrated from their Urheimat in different directions, what is clearly demonstrated by place names. English roots in the name of the Irpin’ River (Old Ukrainian Irpen’) are especially ly transparent.

At right: The Irpen' River.

Photo from the site Foto.ua

This river has a wide boggy valley that should have to be boggier in ancient times. Therefore OE *earfenn, compiled by OE ear, meaning 1. "lake" or 2. “ground”, and OE. fenn “bog, silt”, could have a sense “sludgy lake” or “boggy ground”. The name the city Fastiw (Fastov) is obviously arisen from OE fǽst “strong, fast" and īw, eow “yew-tree”. OE swiera “neck”, “ravine, valley” suits for decoding the name of the village of Skwyra on the Skwyrka River, if k after s is epenthesis, ie inserted sound to give greater expression to the word. In favor of the proposed etymology says the name of the village of Krivosheino formed from Ukrainian words meaning “curved neck” which can be linguistic calque of an older name. The village is located on the river bend.

A latge portion of the Anglo-Saxons remained in Eastern Europe for a long time after their tribesmen moved westward and eventually ended up on the British Isles. In the Sarmatian times the Anglo-Saxons headed the Alan tribal alliance, and after the Hun invasion they moved in search of a free land for settling in the northeast direction and reached the upper Volga. This part of their history is hypothetically restored according to toponyms and is described in the sections:

Anglo-Saxons at Sources of Russian Power.