The Ethnic Composition of the Population of Great Scythia According to Toponymy.

The study of the ethnic composition of the population living along the banks of the Danube, the shores of the Black and Azov Seas, in the Caucasus, on the shores of the Caspian Sea and further north, according to the works of Byzantine historians, began in the 18th century by the Russian historian of German origin I. G. Stritter (BUREGA V .V. 2019, 52). However, this material was not enough to achieve the goals. The rich history of this vast area and its ethnic composition arouse understandable interest among scientists and naturally, they have assumptions that are sought for scientific confirmation. The epigraphic data of Great Scythia or Scytho-Sarmatia, as ancient historians called this large area, are added to the available data of historical documents.

The study and systematization of various substratum onomastics recorded in historical documents and monuments are practically impossible without reliable knowledge about the peoples who inhabited one or another area at different times. This is especially important when historical information is scarce and contradictory. We have this case for the Scythian-Sarmatian time and space. The rich history of this country and its ethnic composition are of great interest to scientists and naturally, they have assumptions that seek scientific confirmation. For several reasons, the most popular was the idea of the exclusively Iranian origin of the peoples of Scythia as a result of a vicious circle in the studies of venerable scientists of the past. Having chosen Iranian languages for phonological-morphological analysis of substrate onomastics, they found confirmation of their assumptions. At present, this approach is assessed quite critically as having a touch of "romanticism" and "voluntarism" in the presence of a clear pre-installation. Being Iranloges, they professed the principle: "What cannot be explained from the Iranian languages, it is impossible to explain at all" (SHAPOSHNIKOV ALEKSANDR KONSTANTINOVICH. 2007: 11-15).

However, the cited author himself did not avoid "voluntarism". Quite rightly, trying to expand the range of languages of the population of Scythia-Sarmatia, he refers to the so-called relics of the Illyro-Celtic, Hittite, and Indo-Aryan appearance, collected by various scientists with an arbitrary interpretation of the available historical information and the results of narrow thematic studies. Meanwhile, studies of the ethnogenetic processes in Eastern Europe using the graphic-analytical method made it possible to establish its ethnic composition for the period from the Bronze Age to the Scythian time (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998, 2000). According to the data received, neither Illyrians, Celts, nor Indo-Aryans, not to mention the Hittites, should have been in Great Scythia. On the contrary, onomastic studies should not only confirm the authenticity of the presence in Eastern Europe in Scythian times of such peoples as the Anglo-Saxons, the ancestors of the Chuvash and Kurds but also establish the ethnic composition of Great Scythia in general.

To establish the ethnic composition of Great Scythia, the Sarmatian onomasticon was compiled using the epigraphy of the Northern Black Sea region and historical documents. For a representative sample of the onomasticon, 315 glosses were selected. The analysis carried out showed that the deciphering of the names contained in it is possible with the involvement of a much larger number of languages than was previously done by other researchers. During the analysis, it turned out that many of the glosses of the list can be deciphered using several languages or are well deciphered in Greek or Latin. Some of the names referred to the Alanian rulers in Gaul and had nothing to do with the Sarmatians. All of them were not included in the representative sample, which included glosses deciphered more or less reliably only with the help of one or several Iranian languages in the amount of 249 units. The calculation showed that the number of glosses of Iranian and Anglo-Saxon origin is more or less the same, and together they make up about half of the sample. The share of Turkic glosses, among which the vast majority are Proto-Chuvashes, accounts for 20%, and the share of Adyghe, transcribed using the Kabardian language – is 13%. The same number is attested for Hungarian and Chechen glosses, and their total share is also 13%. Thirteen glosses were explained in the Baltic languages, two in Armenian, and one in the languages of the Mordovian group. Such a result convincingly testifies to the multinationality of Great Scythia in Sarmatian times and the Iranians did not prevail in it, which is also confirmed by toponymy, although the correlation between toponymy and anthroponymy is not clearly expressed. All the "dark" place names of Great Scythia were deciphered using the same languages and the data obtained was mapped in the Google My Maps system.

Unfortunately, modern toponymy remains without the due attention of researchers, apparently out of the prejudice that it could not be preserved from the Scythian-Sarmatian times. Toponymy differs from epigraphy in that the latter provides information about real people and realities while deciphering place names has a certain degree of probability. The deciphered modern toponymy can provide relevant information only when done not blindly or according to established dubious views, but based on trustworthy research results obtained using extralinguistic methods. The reliability of deciphering increases if place names of the same origin form regular forms – clusters and chains. When they are scattered over a vast space, then their reliability is doubted. In this regard, the recently published work of a specialist in onomastics of the Northern Black Sea region is characteristic. In this respect, the recently published work on the onomastics of the Northern Black Sea region is characteristic (YAYLENKO V.P. 2018). Without taking on the complex work of establishing the entire diversity of the ethnic composition of Scythia-Sarmatia, the author is looking only for Thraco-Dacian traces in a vast area from the mouth of the Danube to the foothills of the North Caucasus. For a certain time, the Thracians dwelled in the area of Fastov and Bila Tserkva, but being driven out by the Anglo-Saxons, they migrated to the Balkans. More clearly, their traces appear exactly where they should have been. In the same places, where neither Dacians nor Thracians have ever been, the interpretation of isolated place names seems far-fetched. This is mainly due to the author's ignorance of the presence in Scythia-Sarmatia of the Anglo-Saxons, Proto=Chuvashes, Kurds, and peoples of the North Caucasus. Below, some of Yaylenko's interpretations will be considered, but for now, we give two examples of his reinterpreted interpretations:

From VI-V centuries. BC Hecataeus, Herodotus, and Strabo mentioned the Thracian tribe of Krobuz (Κρόβυζοι), which populated an area to the south of the Istros delta. Considering the tribe's name "a tough nut to crack", V. Yaylenko believes it is based on Thrak. βυζο- "goat", and he sees the definition for it in the alleged Thrak. *ko/uru, related to ORus. čŭrvenŭ "red" (ibid 48-49). The ethnonym "red goats" is already in doubt, but there is a more convincing interpretation of it when Chuv. kăra "savage, brutal" and puç "head". The ethnonym "savage heads" is in good agreement with the decoding of the name of the tribe of Thyssagetae (Θυσσαγεται) as a "violent people" with the involvement of OE. đyssa "brawler, bully" and Chuv. kĕtü "herd, flock, drove". The Chuvash word reflects the common Scythian word getai/ketai meaning "people", which is present in several ethnonyms (Μασσαγεται, Ματυκεται, Μυργεται a.o.) Almost identical decoding of two different names in different languages testifies to its undoubted plausibility.

The names of the tribes of the Melanchlainoi (Μελαγχλαινοι) and the Harpians (Ἄρπιοι) also have some similar meanings. Herodotus placed the Melanchlainoi north of the royal Scythians and explained their name as "dressed in black" (gr. μελασ "black", χλαι̃να "outer clothing"). The name of the Harpians can also be understood as "men in black", taking into account the OE. earp/eorp "dyed dark". By the time they were mentioned by Ptolemy (2nd century AD), the Melanchlainoi had already crossed over to the right bank of the Dnieper and received a new name, but close in meaning. V. Yaylenko believes that the Harpians were an Illyrian tribe under the assumption that *arb (en) means “Illyrian” (ibid 54 – 55).

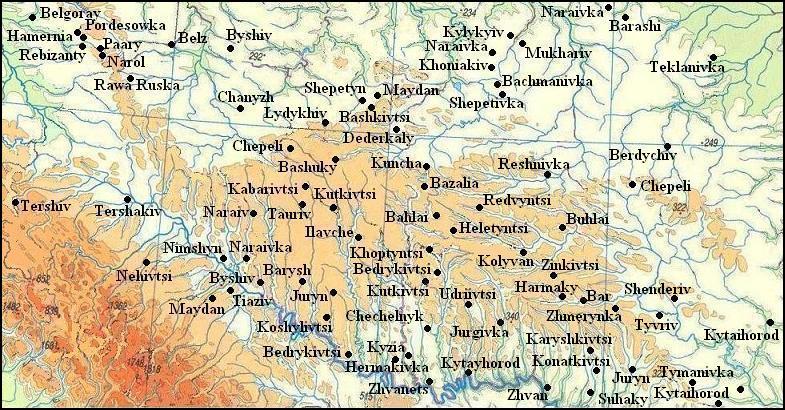

We already know that most of this territory, namely the Steppe zone, Forest-steppe of Right-Bank Ukraine, Carpathian Mountains, and the small spaces in Hungary and Poland were inhabited mainly by Proto-Chuvashes, and then place names should confirm this. As we also know, the ancestors of the modern Kurds, who are associated with Cimmerians, dwelled compactly in Podolia. Anglo-Saxons, that is, Neuroi and Melanchlainoi, cover a large territory on both sides of the Dnieper (see the section "Anglo-Saxons on Ukraine". They also left their traces in the toponymy. Budinoi which are confidently identified with Mordvins by historians left few traces in the toponymy, but the places of their settlements can be localized along the banks of the Sula and Psyol Rivers. Ancestors of the Ossetians (they were obviously Herodotus' Irycai, according to the similarity of this ethnic name to the self-name of Ossetians Iron) dwelled on the upper reaches of the Vorskla and Oskol Rivers. To the east, up to the Volga River was the territory of the Magyars, as we have agreed to call the ancestors of the Hungarians. Quite a lot of names on the territory of Left-Bank Ukraine are decrypted using the Greek language. More or less compact, they are located around the city of Poltava and found scattered in neighboring areas. The distribution of place names of Great Scythia of different ethnicities is shown on the screen of the Google My Maps map, presented below.

The population of Great Scythia in Scytho-Sarmatian times according to toponymy.

The place names of Proto-Chuvash origin are marked in red, burgundy – Anglo-Saxon, dark burgundy – Chechen, blue – Kurdish, dark blue – Baltic, lilac – Mordovian, green – Ossetian, purple – Hungarian, yellow – Greek.

The yellow rhombus marks the Bilsko hillfort near the village of Kuzemin, which some scholars associate with the ancient city of Gelon.

The Scythian hillfort near the village of Khotynets in Poland is marked with a red rhombus.

The red line marks the border of Herodotus' Scythia.

The highest density of Proto-Chuvash place names is observed in western Ukraine. The Proto-Chuvashes dwelled here since the the Corded Ware culture (CWC) time and became successively creators of Komariv and Vysotska cultures. The Proto-Chuvashes dwelled in Poland since the time of the CWC, but there are few Scythian settlements here. They are concentrated mainly in Eastern Poland, where a Scythian hillfort was discovered near the village of Khotyniec in 2016, dating by radiocarbon analysis of the 8th century BC. The archaeological finds of the Scythian type in the rest of the territory can be left by the Scythians during single robbery raids. A large concentration of finds of the Scythian type is observed in Transylvania, but place names do not indicate the mass Scythian penetration here. Scattered place names on the Romanian territory, decrypted using the Chuvash language may refer to the middle of the first millennium AD.

The most massive was the movement of the Proto-Chuvashes from western Ukraine to the east, it is marked by a chain of toponyms of Proyo-Chuvash origin from Chervonograd, Lviv region, to Kirovograd and Cherkasy. It starts above Radekhov and then goes at a distance of 10-20 km from one another through Radivilov to the east and stretches south of Kremenets, Shumsk, and Izyaslav to Lyubar, then turns to the southeast, passes above Khmilnik, through Kalinovka, and there is no longer a chain and a whole strip of place names go in the direction of the Dnieper. The territory of distribution of the Chernolis culture and toponymy testify that its carriers, having crossed the Dnieper, first settled in the Vorskla basin, and then began to develop the steppe part of Left-bank Ukraine. According to ancient historians, most of the Scythian settlements were located here. It can be assumed that some of them have retained their names to this day, despite the "Great Migration of Nations" and subsequent migration waves, which continued until the middle of the second millennium. However, the new migrants were predominantly nomads and not in such significant numbers as to form their own permanent settlements. Historically, people settled in convenient natural conditions and it made no sense for the newcomers to look for new places, therefore, they settled where people had already lived before them. At the same time, very often the name of the settlement remained the same, despite the change in the linguistic affiliation of its inhabitants. This phenomenon is general:

It is known that when some people capture territories formerly inhabited by other nationalities, the names of the localities (toponyms) used by the original settlers are most often preserved by new settlers. A striking example of this throughout history is the fact that many of the place names in North America are of Indian origin, including the names of such large cities as Chicago and Ottawa, both of Algonquian origin (COMRIE B. 2000: 5).

The same applies to other geographic features. In addition, there were always such remote places, where nomads did not get and the indigenous population remained there until the mass invasion of new migrants. The difficulty lies in the fact that when searching Scythian settlements, we use the Chuvash language, which belongs to the Turkic group, but the Turks among the newcomers were quite a few. Tribes of Pechenegs, Cumans, and Tatars inhabited the steppes of Ukraine in turn, and Turkic-speaking Greeks, the so-called Urums inhabit the coast of the Black Sea till now. All they could leave their traces in the toponymy. To distinguish them from place names of Proto-Chuvash origin can be difficult. For example, the names of settlements Temyrivka, Kardash, or rivers Ingul and Sura can be deciphered using the Chuvash and other Turkic languages. However, the Chuvash language is sufficiently different from other Turkic ones phonologically and its vocabulary has many original words, which are absent in other Turkic languages. Conversely, some Turkic names have no good Chuvash matches (Saksagan', Tashlyk). This fact facilitates the search, however, some of the place names, which can be decrypted only using the Chuvash language, can occur since the time of the Khazar Khaganate, when the Proto-Chuvashess populated the same place as their ancestors. Additional research should and can separate all place names such which refer to Scythian times. We can add that during the colonization of the steppe immigrants from other places could bring names of their previous settlements. For example, the name Chuhuiv has its correspondence with Chuhuivka in the steppes. This is an additional complication, but there are few such cases.

With these considerations, work has been begun for searching "dark" place names, incomprehensible for Ukrainians, in the steppes of Ukraine, using the Chuvash and later Old English and other languages. Such geographical objects were found in more than five hundred. We may speak more confidently about the origin of their names when settlements are located in clusters or form chains. Several such chains are seen on the map. No doubt they mark the path of migrants and give an idea of its course. We can assume that the relocation had a long-term nature by small groups, and there was no movement of large numbers of people simultaneously. Settlements in turn were based in convenient locations at a distance of 15-20 kilometers from each other, and sometimes even less. Thus settlers tried not to lose contact with each other. None led this process, and the direction of movement was determined by geographical conditions – mainly by watersheds. Clusters of settlements often consist of three or four units. The only case of a large agglomeration is a group of settlements in the Donbas, whose center lies near the city of Stakhanov (Kadiivka). Here, 15-20 settlements and four rivers with Not-Slavic names are located in an area of approximately 1000 square kilometers. First, the Chuvash language was used for description, but all of a sudden, it was found that the name of the village of Vergulevka in the Perevalsk district of Luhansk Region corresponds well to the OE. wergulu "nettle". Origin of the word F. Holthausen notes as "vague" (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 391), but we can assume that it is related to Latin. *vĭrgĕlla "a little twig", which W. Meyer-Lübke restores according to several Romance languages (MEYER-LÜBKE W. 1992: 782). Since traces of Romance languages in the toponymy of Donbas were not found, one may assume that the name of the settlement once existed on the site Vergulivka was given by Anglo-Saxons. Their presence nearby, namely in the Kharkiv Region is confirmed by toponymy. As for the origin of the Old English word, it should be considered as an Italic substrate on the common ancestral home of Italics and Anglo-Saxons.

After the discovery of one reliable Anglo-Saxon place name, an attempt was made to find others nearby. They have been found, although not in large numbers. Most confidently we can talk about the Anglo-Saxon origin of the name of the river Mius River.

At left: The Mius River

Photo of Оlga GOK. Rostov-on-Don.

Anglo-Saxon offers us the word mēos "moss, swamp" which may be suitable for the name of the river with the marshy floodplain. The name of the river is in common with the Greek name of the Azov Sea Meotian lake or swamp (Μαιῶτις λίμνη). The same root is present in the name of the Kalmiгs River, but it could be named by analogy later as Anglo-Saxon place names were not found on its banks and nearby.

Other place names of possible Anglo-Saxon origin will be discussed in the course of further presentation. It should be recalled that our goal is to establish the ethnic composition of the population of the steppes, and not the desire to find an explanation for all incomprehensible names that can have the most diverse origin, which is of great interest to local history. Accordingly, it is assumed that some toponyms, especially isolated ones, may have different interpretations. Only clusters of place names that can be deciphered using one language can be taken into account, but even among them, there may be random coincidences. Thus, most interpretations are probabilistic, if there are no obvious connections between the name and local natural conditions.

To explain the methods of search and decoding of names let us consider a specific example. There is in Sinelnikovo district of Dnepropetrovsk Region a village of Katrazhka. Chuv. katrashka "a clot", "uneven, lumpy" is suitable for decryption. However Ukrainian words of uncertain origin katraga "a hut" and a diminutive of it katrazhka are known. Perhaps the word was borrowed from the ancient Proto-Chuvashes, but the settlement could be called both Ukrainians and Scythians. Searching logical explanation of which of the names is more suitable for the village, makes no sense because we will never know about the motivation of the people who gave the name. This case was considered doubtful until it turned out that it is part of the chain of Proto-Chuvash place names, and therefore its Proto-Chuvash origin was considered more likely. The mentioned chain begins with the village of Bulahovka in the Pavlograd district of the Dnepropetrovsk region. There are in Ukraine, Poland, and Russia settlements with or similar many: Bulakh, Bulakhiv, Bolekhiv, Bolekhivtsi, Bolokhovo, Bolechów, Bolehówice, Bolkhov. All of them can be decrypted by Chuv. pulăkh "fertility". Further down in the chain, which stretches to the south, such villages are:

Ozhenkivka –Chuv. ăshshăn "warm, affably".

Katrazhka – Chuv. katrashka "a clot", "uneven, lumpy".

Mazhary – Chuv. mushar "firm, strong".

Begma – Chuv. pĕk "to incline", măy "neck".

Garasivka (Harasivka) – Chuv. karas "honeycomb", kărăs "scanty, poor".

Basan' – Chuv. pusă "to suffer".

As already mentioned, the overwhelming majority of Türkic toponyms are Proto-Chuvashsh. Only a few glosses from a representative sample were not explained using the Chuvash language:

Αραβατης (arabate:s), an Alanian mercenary who served under Emperor Isaac I Comnenus – com. Turkic arabačy "coachman".

Ιαφαγος (iaphagos), Olbia, Vasmer – Gag. jafak „horse”.

Ιρβις (irbis), Tanais – com. Turkic irbiz “lynx, leopard”.

Τουμβαγος (toumbagos), Olbia, Knipovich – OT. tom “cold”, baqa “frog”.

Meanwhile, the Turks dwelled in the Sea of Azov Sea area since the Neolithic and gradually populated the North Caucasus. Their descendants are now Kumyks, Balkars, and Karachays. At the same time, the last two peoples inhabit the valleys of the mountainous part of the Caucasus, and in both cases, the Circassians and Kabardians are their northern neighbors. The ancestral home of the Adyghe people was on the territory of modern Abkhazia. With the growth of their numbers, they began settling in neighboring territories, which could not but cause conflicts with the local population. In search of a place to settle, the ancestors of modern Circassians and Kabardians moved to Transcaucasia. This is evidenced by the historically attested names of the Cimmerian leaders, well deciphered using the Kabardian language Teushpa (Kabard. teushcheben “to crush”) and Ligdamis (Kabard. lygye “courage” and dame “wing”). An unsuccessful attempt forced the Cimmerians to seek their fortune in the North Caucasus. In the struggle for a place, the Turks had to give way to the Adyghe tribes and retreated to the mountains. The existence of such a breed of horses as the Kabardian testifies to the settlement of the steppe part of Ciscaucasia by the Adygs for a long time. Breeding this fighting horse from ordinary household horses requires centuries-old selection work, but its result was already evident in Sarmatian times. Among the population of Great Scythia, the Circassians made up a significant part, as evidenced by a representative sample from the Sarmatian onomasticon. Here are some typical examples:

Αβροαγος (abroagos), the son of Susulon, the strategos in Olbia; Αβραγοσ , the son of Sambut, the father of Kharaksen; the son of Khuarsaz (see Χοαροσαζος), Latyshev – Kabard. abragъue „big, high”. Rus. abrek "a man of boundless courage and sacrifice has the same origin."

Bevka, a Sarmatian king – Kabard. bevygъe "wealth, abundance".

Zacatae, a tribe in Asiatic Sarmatia, the territories between the Don and the Volga rivers, Pliny – Kabard. zakъuet "standing side by side".

Zuardani, a tibe i Asiatic Sarmatia, Pliny – Kabar. zauerey "warlike", den "agree".

Ιναρμαζος (inarmadzos), the son of Kukodon (see Κουκοδων), Olbia, Knipovich, Levi – Kabard. in "great", armuzh' "laggard".

Κασκηνος (kaske:nos), the son of Kasag (see Κασακοσ) – Kabard. keskIen "shudder".

Καφαναγος (kaphanagos), the father of Mourdag) (see Μουρδαγοσ), Olbia, Latyshev – Kabard. kъafenyge “dance”.

Κουκοδων (koukodo:n), the father of Inarmaz (see Ιναρμαζοσ), Olbia, Knipovich, Levi – Kabard. kъeukIa "killed", udyn "strike".

Κουκοναγος (koukonagos), the son of Rekhovnag (see Ρηχουναγοσ), a market administrator in Olbia – Kabard. kъeukIa "killed", negu "face".

Μαισης (maise:s), Gorgippia – Kabard. maise “sharp saber, sharp knife”.

Ναυαγος (navagos), the father of Kadanak (see Καδανακοσ), Tanais, Latyshev – Kabard. ne "yey", vagъue "star" .

Ουαχωζακος (ouakho:dzakos), Olbia; Οχωδιακοσ, the son of Dula (see Dula), the father of Azas and Stormais (see Στορμαισ), Tanais, Latyshev – Kabard. egъedzhakIue „teacher”. Liya Akhedzhakova, the actress, Adyghe by nationality.

Ουμβηουαρος (ombe:ouaros), the son of Urgbaz (see Ουργβαζοσ), Olbia – Kabard. IumpIey "naughty, inanimate", uer „boisterous”.

Ουργβαζος (ourgbadzos), the father of Umbevar (see Ουμβηουαροσ), Olbia – Kabard. uerkъ "nobleman", badze "fly".

Ουργοι (ourgoi), according to Strabo one of the Sarmatian tribes – Kabard. uerkъ "nobleman". Cf. Ουργβαζοσ.

Ρηχουναγος (re:khounagos), the father of Kukunag (see Κουκοναγοσ), Latyshev – Kabard. erekhъu "well", negu "face".

Χοζανια (khodzania), female name, Panticapaeum, Latyshev – Kabard. khuedzhyn "spin".

Χοαροσαζος (khoarsadzos), the father of Abrag (see Αβροαγος), Tanais, Χουαρσαζος, Olbia – Kabard. khъuer "parable" sedze "blade of knife".

Very few toponyms of Adyghe origin have been found and they probably belong to later times, that is, the places of settlements of the Adyghes in the Scythian-=Sarmatian time remain uncertain.

Now back to the Kadiivka agglomeration around for considering not Slavic place names having also no explanation in the Turkic languages other than in Chuvash, but can be interpreted by means of the Chuvash, Old English, or Ossetian languages. Noteworthy is that some dark names relate to the railway station:

Borzhykivka, a railway station near the town of Debaltsevo – OE. borg «debt, fualt», ēce «eternal, endless».

Sentyanivka, a railway station on line Luhans'k – Lysychans'k – Os. synt "raven", syntæ "net, snare". This appellative is often found in the toponymy of Ossetia, but it can have a different meaning for place names (TSAGAEVA A. Dz. 2010: 460).

When the railway was laid, the stations were called according to the local names of villages, farms, and tracts. Large settlements did not develop here for a long time because the coal deposits in the Donbas began to be developed only in the 19th century. However, the nearby copper ore deposits have allowed people to mine copper since the Bronze Age. There was a powerful mining and metallurgical center in Eastern Europe, composed of about thirty copper pits. Now smelting copper from the local ore is uneconomical, but in Scythian times the deposit could be not exhausted so people settled in the immediate area. One major place is Kartamishy Mine near the train station Kartamishy. This name can be understood using Old English as "devastated wasteland" (OE. ceart "wild common land" and myscan "to break, ruin"). In this case, the name fits well, because the terrain here could be subjected to human impacts in the extraction of copper ore. There are nearby the Kartamish River and two villages in Ukraine, which have similar names but are far from the copper mines.

Copper Mine Kartamysh

There are three more settlements nearby with mysterious names, explained by folk etymology. There is no point in considering these explanations since similar names exist in other places where they lose their argumentation. Since these settlements are located close to others, the names of which are deciphered using either the Old English or Chuvash languages, there are reasons to use the same languages for their deciphering. Let's consider them in order:

Almazna, a small city in Kadiivka Municipality, Almaznyi, a settlement in the city of Rovenky, Luhansk Region – Chuv. ulma (in the other Turkic languages alma) and çă (pronounced like z'a) the Chuvash affix serving to form nouns from the nominal stems with the meaning of personality, tools, and product of activity indicated in the stem meaning, that is, the word almaz'a could mean a gardener or seller of apples.

Irmino, a small city in Kadiivka Municipality, Luhansk Region – еhe river Irmen', the left tributary of the Ob River, and the village of Irma in the Sheksninsky district of the Vologda region have a similar name, both place names are among the accumulation of other Anglo-Saxon ones. These names come from OE. iermen "big, strong".

Kadiyivka, a city in Luhansk Region – almost the same name Kadyevka has a village in the Yarmolinetsky district of the Khmelnitsky Region, there are two villages of Kadyevo in Russia. All these names must be associated with Chuv. khăt "comfort, convenience", evĕk "kindness" .

Other names of Proto-Chuvash origin may be the following:

Muratovo, a village on the left bank of the Siverskyi Donets River – Old Chuv. bura (Chuv. pura “frame, log house”, tu “do, biuld”.

Pakhalivka, a illage opposite Muratovo – Chuv. pakhal «to appraise, evaluate».

Among this agglomeration, one can see a chain of place names that begins with the village of Karpaty. The locals could not call the settlement by the name the Carpathian Mountains, moreover, the village of the same name exists in the Ulyanovsk Region, close to the Chuvash Republic, and Chuvash dwells in the village. Decoding the name can be considered Chuv. car "to fence off, block" and pat "at all, absolutely". The name of the station Brazol near the town of Lutugino can be understood as "full well" (Chuv. pĕr "full", çăl "well"). This place name for the nomadic peoples is very believable and has a similar name Brazolove village in the Dnipropetrovsk region.

There are a few cryptic names on the opposite side of the mine Kartamishev. Names Bakhmut, Kurdyumivka, and Kodema, obviously have Proto-Chuvash origin, and to the Anglo-Saxon could be considered the following:

Kramatorsk– OE crammian "to press something into something else". The previous name Kram was added by the name of the Torets River.

Holmivs'kyi, a town in Donetsk Region – OE. holm «wave, sea, water»

Hladosove (Gladosove), a town in Donetsk Region – OE glæd «shining, gracious, kind», ōs «pagan divinity».

Korsun', a village and a river in Donetsk Region – OE cors "reed".

The path of the Anglo-Saxons from the area of Kharkiv (the name is from the OE hearg “temple, altar”) to the Donbas is marked by the city of Kramatorsk and the villages of Kartamysh and Volvenkovo. The name of the latter can be explained by OE. fūl “dirty, spoiled”, weng “field, meadow”, which is similar in meaning to the name of the neighboring Kartamysh. Toponyms of Anglo-Saxon origin can also be the names of other settlements in Dobass and in the neighboring Rostov Region of Russia, such as:

Gundorovskaya (Hundorovskaya), a former urban-type settlement within the city of Donetsk, Rostov Region. – OE. hund "dog", ōra"bank, edge".

Kumshatske, a village in the Shakhtersky district of the Donetsk Region – OE. cumb 1. “valley”, 2. "bowl"; sceatt “money, treasure”.

Kumshatskiy, a hamlet in the Millerovsky district of the Rostov Region – like Kumshatske.

Manych, a village in Amvrosievsky district, Donetsk Region – OE manig “many”, ӯce “frog”.

Markino, a village of Novoazovskiy district, Donetsk Region – OE mearc “sign”, “border”.

Rostov–on-Don, a city in Russia – OE. rūst “rusty”.

In the lower Dnieper region, place names of Anglo-Saxon origin have not been found. Only further to the Dniester River, there are quite a few settlements that could have been founded by the Anglo-Saxons. First of all, these are Byrlovka, Holma, Rakovets, Rashkov (three villages), Strutinka (two villages). The name of the country Moldova can also be of Anlo-Saxon origin with OE molde "earth, sand" and wā "trouble, poverty, care". O. Trubachev believed that this name was of Germanic origin, interpreting it somewhat differently using the Gothic language (SHAPOSHNIKOV ALEKSANDR KONSTANTINIVICH. 2007: 515). Probably, the name of the five villages of Viktorovka can also be added to the number of Anglo-Saxon place names. At first glance, this toponym comes from the name Victor. However, in Poland, Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus there are more than six dozen toponyms Viktorov, Viktorovo, and Viktorivka. Such many such names are incredible, given the low prevalence of this name among the Slavs, although some names of settlements may still come from it. However, most of them had to be left by the Anglo-Saxons. OE wīċ "dwelling, settlement" and Đūr/Đōr "thunder god" are well suited for deciphering them. Given the stay of the Goths in the Black Sea region from the 3rd century. AD, it can be assumed that some of the toponyms in these places may be of Gothic origin. A. Shaposhnikov refers to them Belbek, Velibok, Mangup, Murakhva, Piskava, Stil, Stynava, Taniskava, Tyrykhva, and Shivarin, but he does not find a match for all of them in the Gothic language and uses English words for interpretation (ibid: 15-16). The Germanic languages of that period were still quite close, so it is difficult to determine the ethnicity of Germanic toponyms. This problem should have been solved by the Germanists.

The epigraphy of the Northern Black Sea region and other data give grounds to assert that there were no Ossetians among the Scythians, however, in the Sarmatian time, the Iranian ethnic element in the steppes of the Black Sea region began to prevail. Mostly it could be Ossetians and partly Kurds. Obviously, in the Scythian time, the Ossetians remained in the upper reaches of the Vorskla and Oskol, but over time they began to penetrate the steppes in two ways. One went along the Vorskla, and the other along Oskol and Kalitva and further to the mouth of the Don.

Migration Path of the Ossetians from their ancestral homeland to the Caucasus is marked by the Ossetian toponymy. They left such place names in the eastern part of the Great Scythia:

Azov, Sea of Azov and a town – Os. as "the size, number", "adult" (previously "big, large"). The Ossetian word was borrowed from some Finno-Ugric languages where similar words (iso/izo/ots'/udts') have meant either "large" or "small". All of them go back to Gr. ἴσος “equal” of unclear origin (FRISK H. 1960-1972. B. I: 737), that is, they were originally supposed to characterize size. The second part of the word transformed from *av/ov "water", presented in different forms in all Iranian languages. In the modern Ossetian it is contained in æfsurh euphemism for "water".

Bataysk, a town in the mouth of the Don River – Os. bataiyn "to thaw, melt", "to be useful".

Kalitva, some villages and two rivers have this word in their names – the root of Os kælyn "to flow" is added by the attributive suffix -t and *af/ov "water". See Azov.

Khalan', a river, rt of the Oskol River and two villages with similar names on it – Os khalon "crow".

Kotelva, a town in Poltava Region – Os. k'utu "barn", læuuyn "to stay, remain".

Oskol, a river, lt of the Siv. Donets River and two towns with similar names on it – Os. as "size, quantity" (obviously former "large"), kælyn "to flow". Cf. Vorskla.

Tomarovka, a town in Belgorod Region of Russia – Os. tomar "to rush".

Tsimlansk, a town in Rostov Region, Russia – Os. tsym "cornel", lænk "valley, lowland".

Udy (Uda), a river, lt of the Siv. Donets River – Os. ud (udy) "soul, spirit".

Vorskla, a river, lt of the Dnieper River – Os. urs "white", kælyn "to flow".

As can be seen from the distribution of toponymy, the Ossetians migrated to the places of their present habitat along the shores of the Azov and Black Seas. They could not move directly because most of Ciscaucasia had been previously inhabited by Anglo-Saxons (compare the distribution of Anglo-Saxon toponyms on the map above). The area of the Anglo-Saxon settlement here is determined most convincing by such place names:

Right: Anglo-Saxon place names in the Sea of Azov and the North Caucasus.

Yeya, a river flowing to the Sea of Azov and originated names from this – OE. ea "water, river".

Sandata, a river, lt of the Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don River – OE. sand "sand", ate "weeds".

Bolshoy and Malyi Gok (Hok in local pronunciation), rives, rt of Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don – OE. hōk "hook".

Guzeripl' (Huzeripl' in local pronunciation), a settlement in the Maikop municipal district of the Republic of Adygea – OE. hūs "house", "place for home", rippel "undergrowth".

Baksan? a river and a town in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE. bæc "stream", sæne "slow".

Mount Elbrus, mountain peak in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE äl "awl", brecan "to break", bryce "fracture, crack", OS. bruki "the same", , k alternates with s. Elbrus has two peaks separated by a saddle.

Elbrus

Photo by the author of the essay "My trip to Elbrus"

The presence of items of the Scythian type in Central Europe allowed archaeologists to conclude that a large space was influenced by the Scythian culture. The greatest concentration of finds of the Scythian type outside of Herodotus Scythia is observed in Transylvania and Hungary (POPOVICH I. 1993, 250-251). However, it turned out that in the same places, quite a lot of toponyms can have a Proto-Chuvashsh origin. Taking into account the data of archeology, it can be assumed that the Scythians-Proto-Chuvashes crossed the Carpathians simultaneously with the settlement of the Black Sea steppes. Interestingly, the Proto-Chuvash place names stretched out in a chain along the right bank of the Tisza River. Beyond the Danube, the Proto-Chuvashsh place names are concentrated north of Lake Balaton. Migrating, the Scythians-Proto-Chuvashes bypassed the swampy area between the Danube and Tisza rivers. Presently, the swamps are preserved as a large massif at the lower reaches of the Tisza, but in ancient times they could occupy a much larger area. Here are some examples of Proto-Chuvash place names in Hungary:

Arló , a villagein Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County – Chuv urlav “cross-piece”;

Buj, a village in Szabolcz-Szatmár-Bereg County to the north of Nyíregyháza – Chuv puy “rich”;

Bük, a village in Vas County – Chuv pükh “to swell”;

Dunakeszi, a city in Pest County – the first part of the word ші the Hungarian name of the Danube, the second part corresponds to the Сhuv kasă "street, village", a very common formative of Chuvash place names;

Inke, a village in Somogy County – Chuv inke “daughter–in-law”;

Onga, a village in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County to the east of Miskolc – Chuv unkă “a ring”;

Pásztó, a town in Nógrá County next to Buják – Chuv pustav “cloth”;

Sály, a village in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County to the south of Miskolc – Chuv sulă “a raft”;

Tarpa, a village in Szabolcz-Szatmár-Bereg County – Chuv tărpa “a chimney”;

Tura, a town in Pest County – the origin of the name can be out of Chuv tără 1. “a mountain”, 2. “clear” or tura 1. "comb", 2. "divine".

Veszprém , a city – Chuv veç “finish”, pĕrĕm “a skein”;

Zahony, a town in Szabolcz-Szatmár-Bereg County – Chuv çăkhan’ “a raven”;

Zala, the river, flows in Lake Balaton – Chuv çula “to lick”.

From the middle of the 1st millennium AD, the resettlement of the Proto-Chuvashes to the Balkans begins. The traces of Proto-Chuvash toponymy found among others in Romania may be associated with the settlement of the Proto-Chuvashsh horde, which came here under the leadership of Khan Asparuh at the end of the 7th millennium. The most commonplace name in Romania is Măgura. There are 97 of them in Transylvania alone (HALICZER JÓZEF. 1935). If we talk about their origin, we can take into consideration the Slavic gora "mountain", but the prefix ma – is not clear. Most likely, the original form of this type of place-name is a word related to Chuv. măkăr „hillock, hill” while the ending a, was adopted under the influence of Slav. gora. The peoples of Dagestan, where the Khazar Kaganate once ruled, have a similar word magIar "mountain", which must also have a Proto-Chuvash origin. Since this toponym received a general meaning (Rom. măgura "hillock"), it is almost impossible to distinguish the left by the Proto-Chuvashes out of all of their multitudes. However, many of them are plotted on Google Maps in places of accumulation of other Proto-Chuvash place names. These include the following:

Odaia, Odăile, There are place names of this type in Romania about ten – Chuv ută 1. «hay». 2. «island». 3. «valley». ay «low, lowland», uy «field».

Suceava, a city – чув. sět (Old Turc süt) «milk», shyvě «river».

Șipot, Șipote, Șipotu, eight villages have such names – – Chuv shep "beautiful, wonderful", ută "valley".

Tâmpa, a mountain in the city of Brașov – Chuv. tĕm "hill", pü "figure, body", "height, length."

Kurdish place names form three clusters in Eastern Europe. The largest of them is located in Podolia. Here are typical examples of:

Velyki and Mali Dederkaly, villages on the outskirts of the city of Kremenec’ in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. dediri, “a tramp,” kal, “old”;

Hermakivka (Germakivka), a village southeast of Borščiv in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. germik, “warm place”;

Kalaharivka (Kalagarivka), a village to the southeast of Hrymajliv in Ternopil’ Region – Kurd. qal, "to kindle,” agir, “a flame”;

Kokutkivci, a village northwest of Ternopil’ – Kurd. ko, “curve,”kutek “cudgel;”

Mikhyrinci, a village northeast of Volochys’k – Kurd. mexer “ruins”;

Tauriv, a village west of Ternopil’ – Kurd. tawer, “rock”.

Kurdish place names in the Right-Bank Ukraine and Poland

The ancestors of the Kurds dwelled in Podolia in pre-Scythian times. Later they migrated in different directions. Some of them moved westward and became known in history as the Cimbri. The second part, through the Carpathians, migrated to the Balkans and then moved to Asia Minor, where they were taken for the Cimmerians. Their way there is marked by such place names of Hungary, Serbia, and Bulgaria: Ibrány, Gelej, Szelevény, Felgyö, Senta, Temerin, Pancevo, Čačak, Niš, Mezdra, Hisarya, Haskovo, Vize (for more details see the section "Iranic Place Names"). A large concentration of finds of the Scythian type in Transylvania may also indicate the penetration of not Scythians, but Cimmerian Kurds.

In Podolia, some parts of the Kurds remained until the arrival of the Slavs here, as evidenced by separate Kurdish-Ukrainian lexical correspondences. This is also confirmed by the epigraphic data of the Northern Black Sea region, therefore one of the peoples mentioned by ancient historians, in particular, by Herodotus, can be associated with the Kurds. Such a people could be Alazons (Allisons), whom Herodotus placed a little south of the Scythian plowmen in the area where the Dniester (Tiras) and the Southern Bug (Gipanius) are not very far from each other (HERODOTUS, IV, 52). It is in this place that Zhmerinka is located, the name of which is associated with the Cimmerians, that is, the Kurds. Nearby are also settlements of the Vinnytsia region, the names of which are deciphered in Kurdish:

Huncha, a village in Haysyn district of Vinnytsia Region – Kurd. gunc "clay pot".

Chechelivka, a village in Haysyn district of Vinnytsia Region – Kurd. çê "good, best", çêlî "kin, clan, offspring".

Chechelnyk, a town in Vinnytsia Region – see. Chechelivka.

Julynka, a village in Bershad district of Vinnytsia Region – Kurd col (jol) "herd", an – the index of indirect plural.

Juryn, a village in Sharhorod district – Kurd. çoran “flow”.

Maydan, villages in Vinnytsia and Tyvric districts, Maygan Holovchynsky and Maydan Chepelsky, villages in Zhmerynka district – OIr. *maithana "place of residence, dwelling".

Murfa, a river, lt o the Dniester and the village on it of the same name – Kurd. mar (Other Iranian mor, můr) “snake”, av “water, river”. There are similar names of the Morava rivers in Central Europe

Teklivka, villages in Zhmerynka and Kryzhopil districts – Kurd. teklav “mixed”.

Over time, the Alazon Kurds advanced to the shores of the Black Sea. The most convincing evidence of this is the name of the city of Genichesk on the banks of the Sivash, which is also called the "Rotten Sea" because of the unpleasant smell of water. It is this peculiarity that is reflected in the name of the city – Kurd. genî "stinky", "rotten" and çês "taste" in the stem of çêştin "to taste". Perhaps the name Sivash is of Kurdish origin from the names of various salts contained in its water – Kurdish sîwax "lime", "white". Other Kurdish place names might be:

Oleshky, a town in Kherson Region – Kurd. ol “religion”, eşk “appearance, image”.

Tylihul Estuary – Kurd. tilî “finger”, gol “lake”. The last word is borrowed from the Proto-Chuvash language (Chuv. kÿlĕ “lake”). The motivation for the name is explained by the shape of the estuary, stretched out like a finger.

Khorly, a village in Skadovsky district, Kherson region – Kurd. xorol “religion”, possible xorly is the izafet

The name of the Greek colony of Olbia may be also of Kurdish origin, because Gr. ὄλβιος "happy", from which it seems to come, has no etymology. Kurds could be present among the inhabitants of Olbia, as well as Adygs, as evidenced by the epigraphy. The Greeks could call by one name the entire non-Greek population, not only near Olbia but also the entire Northern Black Sea region. And this name was a Cimmerians. A similar name for the Cimbri was that part of the Kurds who went west (see the section "Cimbri"). The ethnonym Cimmerians (gr. Κιμμέριοι, accad. gimirrai) could come from the Kurd. gimîn, gimi-gim "thunder" and mêr "man". The name Cimbri is derived from it.

A small part of those Cimmerian Kurds who reached Asia Minor through the Balkans, moving along the eastern coast of the Black Sea, came to the lower reaches of the Kuban River and settled there. It was here that the ancient historians placed the people of Dandarian (Δανδαριοι). Given that the lower part of the Kuban lies between the Azov and Black Seas, Kurd. darya „sea” and dan „inside”, i.e. „surrounded by the sea” are well suited to explain the ethnonym. The Kurds left traces of their stay on the Taman Peninsula and in the surrounding area also in toponymy:

Gostagayevskaya (Hostahayevskaya in local spelling), a stanitsa (a kind of village) in the municipality of the city of Anapa of Krasnodar Krai – Kurd. hosta "nap, slumber", heyîn "to be, being".

Jemete, a settlement in Anapa district of Krasnodar Krai – Kurd. jêmêtin "to suck off".

Jiginka, a rural locality (a stanitsa) in the municipality of the city of Anapa of Krasnodar Krai on the bank of the Jiga Stream – Kurd. cihê "separate".

Taman', a stanitsa in Temryuksky District of Krasnodar Krai – Kurd. tam "house", anî "forehead".

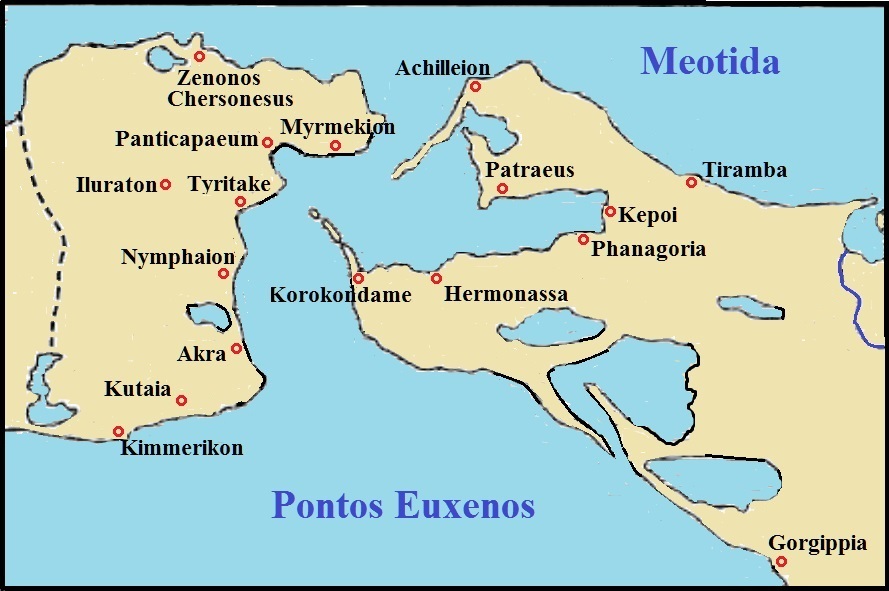

On the Taman and Kerch Peninsulas in the 5th century BC – 6th AD there was the Bosporus kingdom, which included the Azov coast as well as the Don delta. The state was based on the colonial settlements of the Greeks and the prevailing place names on its territory were Greek. However, the name of his Asian capital of the kingdom Phanagoria (Φαναγoρεια) does not have a reliable decipherment in Greek, but can be explained using the Kurdish language – Kurd. fena “disappeared, missing”, gor “grave, tomb”, gorî “sacrifice”. Also, other cities of Bosporus may be of Kurdish origin:

Hermonassa (Ἑρμώνασσα), the second big city on the Taman Peninsula – Kurd. hermê “respect, honor”, nasî “knowledge”).

Tiritake (Τυριτάκη), a city on the Kerch Peninsula – Kurd. ture “angry” take “goat leader”

Cities of the Bosporus (According KRYZHITSKY A.S. 1986: 369).

The presence of Kurds among the population of the Bosporus is also indicated by the name of the city of Kimmerikon in the south of the Kerch Peninsula, and in general, the state was multinational. In addition to the Greeks and, as we see, the Kurds, local tribes of Sinds, Meots, Zikhs, and others dwelled here. Basically, these should have been the ancient Adyghes and Turks of the North Caucasus, but the Kurds can be associated with the Zikhs, if we take into account the Kurds. zîx “brave”, “kind”, “strong”. Under one of the names, some tribe of the Balts may be hiding, which founded their settlements here (cf. Anapa – Lith. anapus “on the other side”; Panticapaeum – Lith. pentis “heel (foot)”, kāpas “hill, grave”, Patraeus – Lith. patraukyti “grab”, etc.). The presence of the Balts in the Northern Black Sea and Azov regions is considered in the article Ancient Balts Outside the Ancestral Home. There, among other evidence, the proper names of people are given, deciphered with the help of the Baltic languages, which can be found in the dark places of the works of ancient historians and epigraphs left by participants or witnesses of real events. Here are some examples:

Βαλωδις (balo:dis), the son of Demetrios, the father of Loiagas (see) – Let. baluodis „dove”.

Βραδακος (bradakos), Panticapaeum – Lith. bradyty, Let. bradît “wade, ford”).

Λοιαγασ (loiagas), the son of Baluod (see Βαλωδις) – Lith. lojà – swearword, lojūgas "Gewohnheitsflucher" (FRAENKEL E. 1962. Band 1: 406).

Μαζαια (madzaia), the daugter of Masteira (see Μαστειρα), Lician, Μαζισ (madzis), Μαζασ (madzas) – Lith. mažas, Let. mazs „small”.

Ουσταναος (oustanaos), Tanais – Lith. austinis "woven".

Παταικος (pataikos), Gorgippia – Lith. pataikus "obsequious".

Σαρον (saron), name of the area on the Borysthenes River according to Ptolemy – Let. sārņi "tailings, slag".

Already in historical times, the Tmutarakan principality existed on the Taman Peninsula and in the lower reaches of the Kuban, the name of which is deciphered using the Kurdish language: Kurd. tarî "dark" (corresponds to the meaning of the first part of the name in Slavonic), kanî "source, spring". The Kurds, like the Adyghes (Circassians), remained in their former habitats, that is, they were part of the population of this principality. From the annals, the leader of the local Circassians Rededya, who was killed by Prince Mstislav the Great in 1022, is known, who in fact could be a Kurd, if we take into account the Kurd red "disappear, disappear", eda "payment, settlement".

The Chechens and Hungarians should have been present in the multinational population of Great Scythia. Their relationship already in the Middle Ages is discussed in the article “Pechenegs and Hungarians”, and here we give an interpretation of several names that are directly related to them:

Αβνωζοσ (abno:zos), Olvia, according to M. Vasmer (ABAYEV V.I. 1979: 284)– Hung. ab „dog” and nyuz “to rip off, flay” (together there may be a “flayer”).

Βαγδοχος (baγdokhos), the son of Simfor (see Σιμφωροσ), the brother of Godigas (see Γωδιγασος) and Dalosak (see Δαλοσακος), Tanais, Latyshev – Hung badogos "tinsmith".

Γιλγοσ (gilgos), the son of Mandas (see Μανδασοσ), Tanais (JUSTI FERDINAND. 1895: 115) – Hung. gyilkos "a murderer".

Σογος (sogos), Gorgippia, Tanais, Panticapaeum, Latyshev – Hung. szagos "odorous".

Αρδαρισκος (ardariskos), Tamais, Latyshev – Chech. ardan “to act”, ritsq “sustenance”.

Θιαγαρος (thiagaros), the father of Midakh (see Μιδαχοσ), Tanais, Latyshev – Chech. tІaьkhьara "last".

Μαχαρης (makhare:s), the son of Mithridates VI Eupator, Kingdom of Pontus (Justi Ferdinand, 1895: 188) – Chech. maьkharan ”noisy, clamorous”.

Οχοαρζανης (okhoardzane:s), the son of Patey (see Πατεισ), Tanais – Chech. oьkhu "flying"aьrzu "eagle", aьrzun "aquiline".

The first results of onomastic research were published almost twenty years ago (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2002) in the hope that other researchers would join the work, but this did not happen. The reason is that no one believes in the existence of a large number of settlements since the Scythian-Sarmatian times. The stay of the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe and the Turkic ethnicity of the Scythians cause skepticism all the more. Specialists dealing with the toponymy of Scytho-Sarmatia are certainly aware of the map of the ancient Greek scientist Claudius Ptolemy published around 150 AD. It does not contain a single toponym from those that were considered above. If any of the mentioned settlements existed, then their absence on Ptolemy's map should have an explanation. It consists of the fact that he might have known cities on the trade routes, which at that time were rivers. Now their names have no reliable interpretation when using the languages of those peoples who, according to the generally accepted, but erroneous opinion, lived in the Northern Black Sea region and migrated to new places of residence long ago. The population along the lines of communication could change throughout history and at the same time, the names of cities could change. Deaf villages away from the highways, in which a permanent population of the same ethnicity dwelled, were unknown to ancient historians. The constancy of the population ensured the preservation of the original names acquired by newcomers. Nevertheless, large cities could have retained their name to our times, albeit in a slightly different form, and the disappeared names should at least be deciphered using Old English or Chuvash languages. Let's check this assumption by analyzing Ptolemy's map (see below).

A fragment of Ptolemy's map

Let's start with Borysthenes (Βορυσθένης), whose name is not considered to be Greek but, in Shaposhnikov's opinion, has nothing to do with the Iranian languages, and attempts to interpret it based on Indo-Iranian or Slavic languages "look too artificial" (SHAPOSHNIKOV A.K. 2005, 39). The interpretation of the name of the river using the Old English language may be more plausible – cf. OE bearu, g. bearwes "forest", đion "to grow, develop". The Germanic root of the last word is restored as đenh [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 250], that is, the ancient name of the Dnieper can be explained as "overgrown with forest". Ptolemy's map shows such settlements downstream of Borisfen, the motivation for the names of which is still being considered: :

Anagarium – OE. ān "one", "single', eagor "flood, sea".

Amadoca – V. Yaylenko tries to prove that the name is Thracian (YAYLENKO V.P. 2018. 50-52), and this may be, but other possibilities are not excluded– 1. OE. hām “(native) home”, “dwelling, village”, hāma "a little village"; dōc "bastard" (the Anglo-Saxons could pejoratively call other tribes by bastards); 2.Chuv. mătăk 1. "short, scanty", 2. "quarrelsome, quarrelsome", –a is a prosthetic vowel.

Sarum – OE. sear "dry".

Serimum – OE. searian "to dry up".

Ordessus – OE. ord "spearhead", æsc "ash, spear".

Niconium – OE. niccan "to deny".

On the right tributary of the Dnieper without a name on the map (Pripyat?), Ptolemy designated the following objects:

Amadoca Palus – the generally accepted understanding of the name – "Lake Amadoc", obviously due to the location of the object on the shore of the lake. It was supposed to be palus – "lake", but in what language? Nothing better than OE. pōl, "big puddle, small body of water" has not yet been found. In such a case, the name Amadoca should be interpreted using Old English.

Leinum – OE lean "reward, gift".

Sarbacum – OE sear "dry", bæc „stream“.

Niossum – OE. neosian "to look, view", sum „something“.

Metropolis – "main city" (Gr. μήτηρ "mother", πόλις "city"). Obviously, this meant Kiev.

Ptolemy's map shows the Carcinites River flowing into Karkinit Bay, but there is currently no large enough river in this place. Perhaps it existed in ancient times, and a small part of it remained in the form of the Kalanchak River. Etymon carcinit can be associated with OE. carcian "take care" and nieten "small livestock". Downstream of the river, the following settlements are indicated:

Tracana – OE. đræc “pressure, force, violence”.

Ercabum – OE. Erce – the name of the goddess (Mother Earth), beam, OE. bōm "tree".

Torocca – OE. toroc "caterpillar", cahh,cio "jackdaw, jay".

None of the toponyms listed above could be associated with modern ones, just as modern toponyms in these places could not be deciphered using either Old English or Chuvash (see Google My Maps map above). Obviously, this territory did not retain a permanent population in the process of repeated invasions of the nomads from Asia.

The name Tiras can be associated with the Chuv. tür/türĕ. The word has several meanings, among them – "straight", "honest", "frank", "peaceful", and "calm". A similar definition had Tanais (the Don River) – Chuv. tănăç "calm, quiet". Downstream of the Tiras, that is, the Dniester, on the map of Ptolemy, are indicated:

Carrodunum – OE. carr “stone”, dūn “hill”. Approximately in this place, the modern city of Gorodenka is located and on the outskirts of it there is Chevonaya Mountain.

Maelonium – OE. meolo “flour”, at this place, the city of Melnytsia Podilska (Podolian Mill). Obviously, the flour-grinding craft has existed for a long time here.

Arcobadara – Lat. arca "cash box, treasury", OE earc(e) "box", bādere "tax collector". Obviously, the Old English word was borrowed precisely in the Scythian time.

Clepidara – OE. clipian "speak, shout", deor "beast".

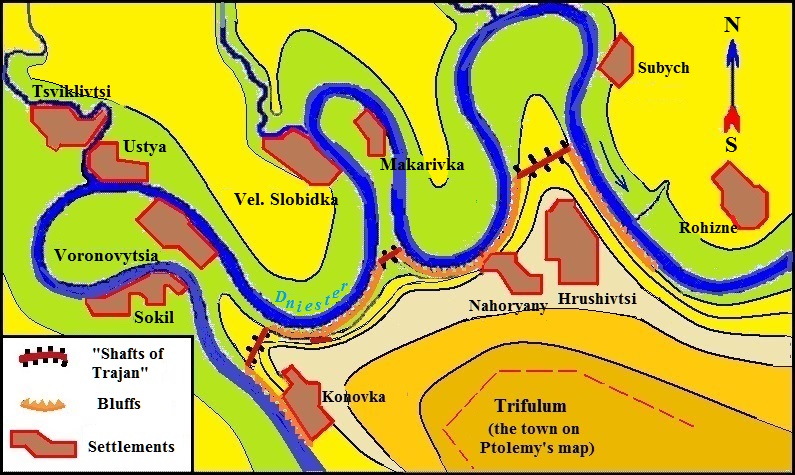

Trifulum – OE. đri “three” fulla "height". At this point, the Dniester makes three loops. The three hills formed in this way are separated from the gently sloping banks by moats and ramparts that have survived to this day. They stretch across the loops from one river to the other. Together with the steep banks, they form a continuous line of defense (see diagram below).

Fragments of "The Ramparts of Trajan" on the right bank of the Dniester in the Kelmenets district of the Chernivtsi region.

The maroon lines indicate artificial defensive structures (ditch and rampart)

The red lines are the steep banks of the Dniester.

The black contour lines indicate the height of 200 m above sea level.

Such combined defensive lines can be found elsewhere. In particular, a closed line of defense is formed by the Dniester, its left tributaries Zbruch and Nichlava, together with man-made ramparts in those places where the banks of these rivers are flat. It can be assumed that they form the boundaries of some pseudo-state formations of bygone times. Without reliable archaeological evidence, it is impossible to talk about their belonging. In the case of Trifulum, such evidence is already emerging. There have been reports on the Internet that archaeologists have found one of the largest settlements of late antiquity on the territory of Ukraine near the village of Buzovitsa, Dniester district, Chernivtsi Region. There are several place names in the immediate vicinity that can be deciphered using Old English:

Kelmentsi, an urban-type settlement in Chernivtsi Region – OE. gielm "a handful, a bundle, a sheaf."

Lenkivtsi, a village in Dniester district of Chernivtsi Region – OE. leng "length, height".

Vartykivtsi, a village in Dniester district of Chernivtsi Region – OE. weard "watchman, shepherd, protector."

Putsyta, a river, the rt of the Dniester in the Chernivtsi region. – OE pucian "to crawl", "stringent", "whippy". This combination of meanings already indicates the correctness of the interpretation, but one of the streets in the city of Borovichi, Novgorod region in Russia, bears the same strange name. It could be equally suitable for the name of both a river and a street, and this casts aside any possible doubts. The treasure of Kufic dirhams found in Borovichi and the nearby toponymy also indicate the presence of Anglo-Saxons in those places.

Restev-Ataki, the former name of the village of Dnistrivka in the Dnister district of the Chernivtsi region. – OE. rest "rest", eow "yew".

Thus, there is reason to believe that the city of Three Heights was the capital of some pseudo-state formation of the Anglo-Saxons on the right bank of the Dniester. To protect their territory from possible attacks by nomads, they built a defensive line using the area's natural conditions in the middle of the first millennium wave after wave swept from Asia to Central Europe.

To the east of the mouth of the Dniester, Ptolemy's map shows the seaside town of Physca (Fusca). Abaev assumed that now a small village "Sukhoi Liman" is located in this place and explained the name of the city from Os. xusk' „dry, barren land”, but V. Yaylenko considers such an interpretation unreasonable for phonetic reasons and suggests the origin of the name from the Greek verb φύειν “to grow, arise” with the iterative suffix -σκ- (YAYLENKO V.P. 2018, 44-45). You can also think that the city was named after the Roman commander Cornelius Fuscus, who died in the battle with the Dacians. In the ancient world, there are several similar toponyms,, like the name Fusca, which can come from lat. fuscuc "dark".