Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Russia

After the accidental discovery of Ukrainian toponyms deciphered using Old English twenty years ago (STETSYUL VALENTYN. 2002), an attempt was made to search for new data, which turned out to have completely unpredictable consequences. As it turned out, the capital of Russia, Moscow, just like many other historical cities of this country was founded by the Anglo-Saxons. There were so many toponyms of supposed Anglo-Saxon origin that this forced a significant change in the understanding of known historical processes, which resulted in the need to consider new historical topics(see "Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe", "The Ethnic Composition of the Population of Great Scythia According to Toponymy.", "Anglo-Saxons at Sources of Russian Power", "Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Asia, "Alans – Angles – Saxons", "Khazars"). It is very unfortunate that academic science completely ignores my research. In private correspondence, recognized authorities told me that my evidence was inconclusive. I don’t know what facts indicating the presence of Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe could be more convincing than deciphering the names of seven villages Bibirevo in Russia with the help of Old English. by: “group of houses” in place names (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974, 39), and by:re “shed”, “hut”, "shack" (ibid., 40).

No less convincing is the name of the village Dydyldino, as part of the urban settlement of Vidnoye, Leninsky district, Moscow region, with the involvement of OE. dead “dead”, ielde “people”. The meaning of the name "dead people" fits well with the fact that there has been a burial place for people here since ancient times. Near the village, there are burial mounds presumably dating back to ancient Russian times. In the scribe books since 1627, a church in the name of Elijah the Prophet is listed in the village, the dilapidation of which was noted already at that time. According to legend, at the beginning of the 15th cent. a convent was founded here by Dmitry Donskoy’s wife Evdokia Dmitrievna. At the church, there is a currently operating Dydyldinskoye cemetery, well known in Moscow, about which the following information was found:

Even at the time of the founder of the monastery, the Cathedral Ascension Church became the last resting place for female persons from the reigning family. In the cathedral were the graves of the Grand Duchesses, the wives of Tsar Ivan the Terrible, beginning from Anastasia Romanovna and ending with Maria Fedorovna – the mother of Tsarevich Dmitry, who was killed in the town of Uglich. Here were the tombs of the queens, and the wives of the kings from the house of the Romanovs. The last burial is dated 1731. Then, niece of Peter the Great (daughter of the half-brother of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich) Praskovya Ivanovna was buried in it (Historical reference on the Official website of the administration of the urban settlement Vidnoye of the Leninsky municipal district)

For Russian linguists, the topic of Anglo-Saxon toponymy should have been the closest and most interesting, but it was in Russia that the most biased attitude towards my research was formed. However, the search for Anglo-Saxon toponymy continues to this day and gradually the search area was expanded to the entire continental Europe. There are currently almost 1,500 toponymic units of suspected Anglo-Saxon origin listed on GoogleMyMap. Of these, approximately one-third is located in Russia. As a side material, Anglo-Saxon toponymy is used in the articles mentioned above, but only a small part of it. Most of all it is discussed in connection with the establishment of Russian statehood on the basis of the Grand Duchy of Vladimir. However, in the area of Novgorod and Pskov, there are no less Anglo-Saxon place names. At the same time, it is striking that they form a chain from Novgorod to Kyiv, clearly expressed on the map. It can be associated with the path “from the Varangians to the Greeks.” Some of the place names in this chain, as well as in other places, can be deciphered using a dictionary of the Old Icelandic language, which is considered the “classical language of the Scandinavian race” (An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Preface). It is difficult even for Germanists to separate them, but preference is given to Old English for various reasons, including because North Germanic toponymyis considered separately and is not associated with the Varangians. The conclusion about Scandinavian colonization on the territory of Ancient Rus' is erroneous, because “none of the ancient Russian large urban centers bears a name that would be explained accordingly; none of them were founded by Scandinavian aliens» (RYDZEVSKAYA E.A.. 1978, 136). In addition, as the analysis showed, many Russian place names phonetically always correspond better to Old English words than to Old Icelandic ones in cases where there is a difference between them. For example, to decipher the name Churilov, OE ceorl is phonetically better suited than OIc karl, since the derivative from the latter would have to have the form Karlovo. There are also quite a few supposedly Germanic place names that cannot be deciphered using Old Icelandic at all. An analysis of historical documents shows that the Varangians had no reason to found their own settlements:

There is not the slightest indication of the occupation of uninhabited territories by overseas newcomers, the clearing and cultivation of lands untouched by culture, the development of their natural resources, etc. As for the inhabited areas, here too they were interested in something else: at first, robbery and tribute, and later those trade relations that connected them with local shopping centers. The goal, no less important and tempting for their hired service in Rus', was not the acquisition of land holdings, but salary and booty (vassalage without fief relations K. Marx). There is no doubt that they not only often visited our country in the 9th-11th centuries, but also settled there in some cases; this, for example, was the case in Ladoga, Novgorod, Kyiv, and Smolensk Gnezdovo (ibid: 135).

Thus, there are good reasons to believe that the chain of place names from Novgorod to Kyiv was left by the Anglo-Saxons. Here are the most convincing examples from it in the direction from north to south:

Farafonovo, a village in Novgorod district of Novgorod Region – OE. faru “trip”, fōn “to take, begin, undertake”, which is a good name for the beginning of a journey.

Shimsk, the administrative center of the Shimsky municipal district of the Novgorod region – OE scima “ray, light, radiance.”

Марково, a village in Stara Rusa municipal district of Novgorod Region – OE. mearc, mearca “border”, “sign”, “district”, “designated space”. In total, there are more than a hundred settlements with this and similar names in Russia. It is very doubtful that all of them came from the less common name Mark.

Markovo, a village in Belebelkiv rural settelment of Poddorskiy district of Novgorod Region – see above.

Frinevo, a village in Poddorskiy district of Novgorod Region – OE. grien "sand, gravel".

Seleyevo, a village in Poddorskiy district of Novgorod Region – OE. sele"house, dwelling".

Fenevo, a village in Andreapolsky district of Tver Region – OE. fenn "swamp, bog".

Moskva, a village in Penovsky district of Tver Region – OE mos "bog, swamp", cofa "a hut, pigsty".

Fishovo, a village in Andreapolsky district of Tver Region – OE fisc "fish".

Fofanovo, a village in Zapadnodvinsky district of Tver Region – OE. fā "motley", fana "fabric, scarf".

Berkovo, a village in Zharkovsky district of Tver Region, a village in Vladimir Region – OE. beorc "birch".

Boldino, a village in Dukhovshchinsky district of Smolensk Region – OE bold "house, dwelling".

Markovo, a village in Dukhovshchinsky district of Smolensk Region – see above.

Boldino, a villave in Kardymovsky district of Smolensk Region – см. выше.

Sinkovo, a villave in Smolonsky district of Smolensk Region – OE. sink "treasure, wealth".

Ryazanovo, a village in Smolenski district of Smolensk Region – OE. rāsian "to study, experience".

Levkovo, a village in Monastyrshchinsky district of Smolensk Region – OE. lēf "weak", cofa "hut, shack, stable".

Further, the chain of Anglo-Saxon place names continues on the territory of Belarus and Ukraine. In Russia, it is necessary to note the accumulation of Anglo-Saxon place names in the area of the ancient town of Borovichi, Novgorod Region. It is famous for the fact that a treasure of Kufic dirhams was found there. The Anglo-Saxons took part in trade with the East along the Volga route and could stock up on goods in these places, buying furs, honey, and wax from the local population and paying for all this in dirhams. In the city itself, there is a street Pucita, the name of which can be associated with OE. pucian "to crawl". A small tributary of the Dniester has the same name approximately in the place where the city of Trifulum is located on Ptolemy’s map. It is assumed that here at the beginning of the new era, there was a certain pseudo-state formation of the Anglo-Saxons (see The Ethnic Composition of the Population of Great Scythia According to Toponymy). Near Borovichi, on an area of twelve thousand hectares, the following settlements of Anglo-Saxon origin are closely located:

Velgia – OE. welig "willow".

Yegla – OE. egle "annoying, painful".

Коремера – OE. coren "selected", mera "incubus".

Kruppa – OE. cropp(a) "fart, bunch".

Марково – OE mearc "border, end, section".

Putlino – OE pyttel "falcon".

Shibotovo – OE scippan "create".

Toponyms of supposed Anglo-Saxon origin are densely located in the Pskov region. Their number exceeds four dozen units, of which 11 are called Markovo. Other names include Boldino, Velye, Grinevo, Levkovo, Fenevo, the origin of which was discussed above. Here are some more examples:

Gavrovo, villages in Dnovsky and Opochetski district – OE gearwe "good, sufficient, complete".

Goldino, a village in Pskov district – OE gold "gold".

Fatyanovo, a village in Novorzhevsky district – OE fatian "to receive, get, achieve".

Fofonkovo, a village in Krasnopurdski volost of Pskov district – see Fofanovo.

Chertovo, a village in Sebezhsky вistrict – OE. ceart "wasteland, uncultivated public land".

Churilovo, villages in Pustoshkinski and Ysvyatski district – OE. ceorl churl "peasant, husband, man".

On the territory of European Russia, the most common toponyms are the already mentioned Markovo (95 cases), Churilovo (27), Levkovo (24), Ryazanovo (22), Fatyanovo (18), Boldino (13), Sinkovo (11) and Shadrino ( 16), it is very difficult to find an interpretation of the name of the latter. In total, there are 25 villages with this name in Russia. Some of them may come from the dial. shadra “smallpox”, but the prevalence of this toponym raises doubts about such an interpretation for the predominant number of cases. Usually, names with negative connotations are very rare. M. Vasmer does not consider the origin of this word, so we can assume its origin from Old English. *sceader from scead “shadow, protection, guard.” This assumption is due to the existence of the Russian word shater, which is considered to be a borrowing from Turkic, the primary source of which is supposedly Persian čadr with Hungarian mediation (VASMER M. 1973, volume IV, 413). The Hungarians were never present in Asia, so it must be assumed that the Turks borrowed the supposed Old English word from the Anglo-Saxons after they arrived in Asia. It is impossible to explain the origin of the toponym Shadrino otherwise.

Among other toponyms of Russia of Anglo-Saxon origin, the following can be noted:

Bryansk (chronicle Bryn' – according to Tatishchev) – OE bryne "fire"; the name may have been given during the times of slash-and-burn agriculture.

Valday, a town in Novgorod Region, two villages in Karelia – OE. weald "forest", ā "eternal".

Velye, seven lakes in different regions of Russia – OE. wel "well", ea "water".

Volfa, a river, lt of the Seym, lt of the Desna – OE wulf, "wolf".

Volkhov, a town, a settlement, and a river in Leningrad Region – др.-англ. "wulf".

Vytebet', a river, lt of the Zhizdrs, lt of the Oka – OE wid(e) "wide", bedd "bed, channel".

Kitay-gorod, a historical district in Moscow – OE ciete "hut, little house".

Kotlas, a town, Arkhangelsk Region – OE. cot "hut, cabin", læs "pasture".

Lukovets, an ancient settlement in the Novgorod Land, flooded by the Rybinsk reservoir, a town and village in the Oryol region, a village in the Pskov region. – OE. loca "locking", "blockade", wīċ "dwelling, house".

Onega, a town and a river in Arkhangelsk Region, Lake Onega – OE. on-œgan "to fear".

Romodan, a village in Alexeyevsky district, Republic of Tatarstan – Oe. rūma "place", dān "damp, humid place".

Romodanovo, village and hamlet in the Ryazan Region, a village in the Smolensk Region, part of the city of Kaluga, a village in Mordovia – like Romodan.

Ryazan, a city and five villages in Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Moscow and Smolensk Regions – OE. rāsian "to study, experience".

Seliger, ф lake in Tver and Novgorod Кegions– ЩУ. sælig "blessed", ār "messenger".

Sinkovo, two villages and two hamlets in the Moscow Region, two villages each in the Smolensk and Tver Regions, a village in the Bryansk Region, and a village in the Yaroslavl Region. – OE. sinc "treasure, wealth".

Anglo-Saxon place names in Eastern Europe

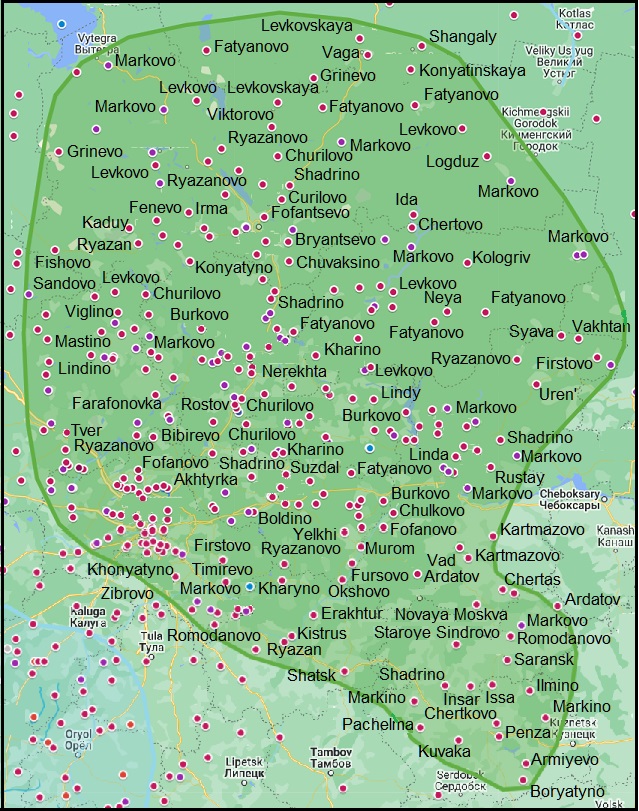

On the map, settlements of Anglo-Saxon origin are indicated by burgundy dots. Hydronyms are indicated in blue. Separately, settlements such as Markovo/Markino are indicated in purple.

The ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons is colored red, blue is the territory of the Sosnitsa culture, and green is the territory of the Rostov-Suzdal principality. The territory of the Vladimir-Suzdal Principality is highlighted in dark green, the boundaries of which are determined according to historical data, taking into account the density of Anglo-Saxon toponyms

The undoubted presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe and especially their connection with the route from the “Varangians to the Greeks” raises the question of their relationship with the Varangians with all severity. Toponymy cannot answer this question; other sources must be used. First of all, we should start with the fact that the Varangians did not call themselves by this name, and there is no suitable word in the North Germanic languages:

The Scandinavian origin of this word is also refuted by the famous Soviet linguist P.Ya. Chernykh. He convincingly, strictly scientifically proved that the etymology of “Varangian < vaeringiar” does not stand up to criticism either from a semantic or chronological point of view. Since, according to the Norman theory, Sweden (more precisely, the eastern coast of this country) is considered the homeland of the Varangians, it is important to note that in the written monuments of the ancient Swedish language, there is no nominative case, either singular or plural, or any other equivalent Swedish form with the same basis. This means that in this language the word we are interested in cannot be the original (AKASHEV A.Yu. 2013).

Other peoples could call foreign tribesmen Varangians. There is no convincing interpretation of the word using Slavic languages, despite numerous attempts to do this, so it can be assumed that the Varangians got their name from the Anglo-Saxons. The Old Saxon word was war(a)g "criminal", which in Old English corresponds to wearg "outcast" ", "damned", "criminal". By the time the Varangians arrived in Kyiv, the city was ruled by the Princes Dir and Askold, who, judging by their names, were Anglo-Saxons: Dir – OE. diere “dear, valuable, noble”, Askold – OE. āscian “to ask, demand”, “to call, to choose” and ealdor “prince, lord”, that is, “elected prince”. Considering the tense relations between the Anglo-Saxons and the Varangians that developed after the treacherous murder of the Kyiv princes by Varangian Prince Oleg, the proposed interpretation of the word “Varangian” is quite plausible (for more details, see "Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe").

The highest density of Anglo-Saxon place names is observed in the territory of the former Vladimir-Suzdal principality and especially around Moscow (see Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe). From time immemorial, Finno-Ugric tribes inhabited these places, and the Slavs moved here only at the end of the first millennium AD, but even before their arrival the cities of Rostov, Suzdal, Murom, and Ryazan already existed here. The names of these cities cannot be deciphered by either the Finno-Ugric or Slavic languages, and the question of their founders remains open. However, their explanation suggests that they were founded by the Anglo-Saxons:

Rostov, – OE rūst "red", "rust". Cf. Murom.

Suzdal, a city in Vladimir Region – OE. swæs "nice, pleasant, loved", dale "valley".

Tver (in the chronicles of Tkhver, Tfer, and others similar) – OE. đwǣre “obedient, pleasant, happy.”

Murom, a town in Vladimir Region – OE mūr "wall", ōm "rust".

Ryazan – OE. rāsian "explore, investigate".

Anglo-Saxon place names on the territory of the Vladimir-Suzdal Principality

Berkino, villages in Moscow and Ivanovo Regions – OE.- berc "birch".

Linda, a village in the urban district of the Nizhny Novgorod Region, Lindy, a village in the Ivanovo Region, the village of Lindino in the Tver Region. – OE. lind "linden".

Moscow (in the chronicle Moskovĭ or Moscowǔ), the capital of Russia, villages Moskvain the Tver and Novgorod Regions – OE. mos "bog, swamp", cofa "hut, shack."

Nero, a lake in the Yaroslavl region, on the banks of which Rostov is located – OE neru "salvation, provisions."

Penza – originally the name of the city was similar to Lat. penso, -āre “to weigh”, “to evaluate”, “to pay” was given by the Italics who migrated to the east (see Ancient Greeks and Italics in Ukraine and Russia), The Anglo-Saxons slightly changed its sound following OE pæneg “coin, money”. Cf. Hungarian pénz "money".

Firstovo, two villages in Nizhny Novgorod and one in the Moscow RegionS – OE. fyrst "frst".

Fundrikovo, village in Nizhny Novgorod region – OE. fundian "to strive, to desire", ric "power, wealth."

Fursovo, seven villages in Kaluga, Ryazan, Tula, and Kirov Regions – OE. fyrs, a plant "Genísta".

Yurlovo, three villages in Moscow and one in Pskov Regions – OE. eorl "noble man, warrior", "earl" in the Middle Ages.

There are especially many supposed Anglo-Saxon settlements on the territory of Moscow and in the immediate vicinity. Their density is such that it makes sense to show their location on a separate map (see below)

Some names on the map were given above, but for the rest the following are offered:

Akhtyrka – OE. eaht "advice, discussion", rice "power, government."

Belyi Rast – OE. ræst "rest, peace."

Darna – OS. darno, OE. darnunga "secret, hidden".

Chertanovo – OE ceart "wasteland, uncultivated public land".

Dedenevo – OE. dead "dead", eanian "to lamb".

Fofanovo – OE. fā "motley", fana "cloth, scarf."

Kartino – OE. ceart "wasteland, uncultivated public land."

Kartmazovo – OE ceart "wasteland, uncultivated public land", māg "bad".

Kitaygorod – OE. ciete "hut, shack, booth."

Kuntsevo – OE. cynca "bundle, bunch."

Ladoga – OE lāđ "dangerous, hostile", OS -gā, OE. -gē "gau, area".

Lytkarino – OE. lyt "little", carr "stone, кщслЭ.

Mamyri – OE. mamor(a) "deep dream".

Miusy, historical district of Moscow – OE. mēos "moss, swamp."

Oboldino – like Boldino.

Penyagino – OE. pæneg "coin", "money".

Reutov – OE. reotan "cry, complain."

Sinkovo – OE. sinc "treasure, wealth."

We can add to these oekonyms also the names of the Moscow rivers Neglinnaya and Yauza. OE nægl “nail, peg” is phonetically well suited for the first. A derivative from it nægling (the name of the sword) is also recorded, but the motivation for this name of the river remains unclear. The name Yauza can be found in chronicles in the form Auza, so OE eage “eye, hole” (Old Norse auga) is also well suited for decoding, although in this case, the motivation remains not entirely clear too. However, the right tributaries of the rivers Lama and Gzhat' have the same name.

The considered toponymy was mainly left by the Anglo-Saxons after they migrated from the Northern Black Sea region, from where they began to leave at the beginning of the Hunnic invasion at the end of the 4th century AD. A small part of the place names dates back to the existence of the Sosnitsa culture, the creators of which were the Anglo-Saxons, who came from the banks of the Dnieper to the territory of the Kursk and Bryansk Regions one and a half thousand years earlier. In the Scythian-Sarmatian period, the long ascent of the Anglo-Saxons in world history began in the Donbas.

As the cluster of place names around the Kartamysh copper mine north of Debaltsevo shows, the Anglo-Saxons settled here near the Scythians. Having taken control of the copper mining industry and metalworking, they achieved economic superiority over the foreign-speaking population of the Northern Black Sea region and, as a result, political dominance:

New archaeological materials allow us to say with confidence that in the Donbas, at least in the Late Bronze Age, there was a large mining and metallurgical center, where they not only mined ores and smelted copper but also supplied neighboring territories with manufactured tools, metal and ore. As E.N. Chernukh rightly noted, the localization of copper deposits allowed the tribes, that developed them, to obtain a new powerful source of enrichment, and thanks to their metal, the mining and metallurgical centers subjugated vast territories to their influence (TATARINOV S.I. 1977: 206).

Fleeing from the Huns, the Anglo-Saxon-Alans of Donbas en masse went to Western Europe, but a small group of them found refuge in the North Caucasus and there is evidence of this in local toponymy (see map below).

Right:Anglo-Saxon toponymy in the Azov region and the North Caucasus.

The place names mark the route of movement of the Anglo-Saxons from the Donbas to the foothills of the Caucasus and their settlements in Caucasian Alania. The most convincing examples are:

Yeya, the river flowing into the Sea of Azov and derivatives from this name – OE. ea "water, river".

Sandata, a river, lt of the Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don, and the village on the bank of this river – OE. sand "sand", ate "weeds".

Big and Little Gok, rivers, rt of the Yegorlyk, lt of the Manych, lt of the Don – OE. hōk "hook".

Sengeleyevskoye, a village in Shpakovsky District of Stavropol Krai – OE. sengan "burn", leah "field".

Guzeripl, a rural locality in Dakhovskoye Rural Settlement of Maykopsky District in Adygea – OE. hūs "home", "place for home", rippel "undergrowth".

Baksan, a river and a city in Kabardino-Balkaria – OE. bæc "stream", sæne "slow".

Mount Эльбрус, the highest mountain in Russia and Europe – OE äl "awl", brecan "to break", bryce "break, crack". Here there is an alternation of posterior palatal k and s. Elbrus has two peaks separated by a saddle.

Elbrus

The photo by the author of the essay "My trip to Elbrus (in Russian)"

Continuing to play a leading role in the political life of the Black Sea region, the Anglo-Saxons united in one state formation the entire population of the North Caucasus, which gave rise to the Khazar Kaganate (см. Khazars). The name of one of the rulers of the emerging state, Sarosiya (512? -596), can be deciphered using Old English. searo "skill, mastery".

The final phase of the history of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in Russia is also reflected in toponymy (see "The Development of Siberia and the Far East"). The secret state archives of Russia should preserve documents from the Crimean War (1853-56), which can confirm the assumptions made about the events that took place in the Far East in the mid-19th century. Their publication could be a serious impetus for the study of Anglo-Saxon place names at a higher level.