Ancient Germanic Onomastics in Eastern Europe.

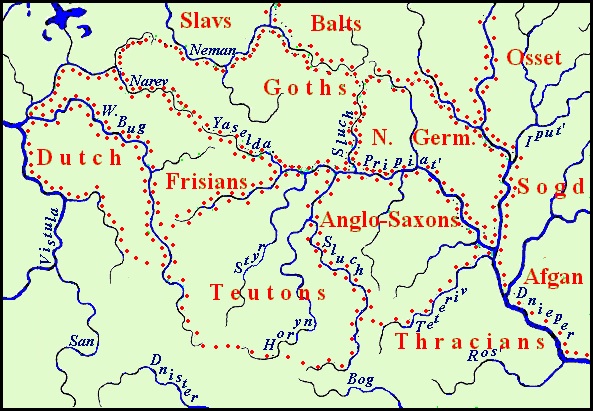

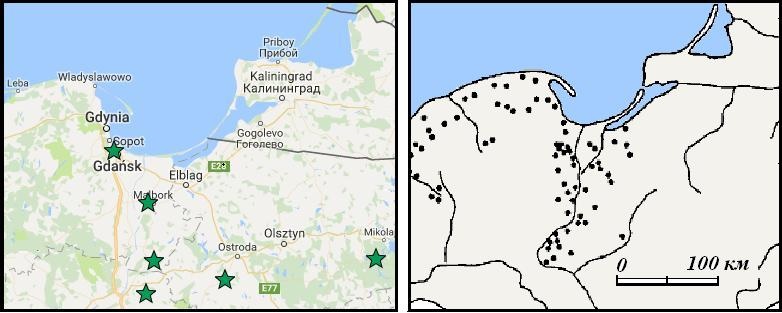

The Urheimat (ancestral home) of the Germanic peoples on the whole Indo-European space, which was determined using the graphic-analytical method, was located in the area between the Neman, Narev, Yaselda Rivers, and its eastern boundary was the Sluch River, the left tributary (lt) of the Pripyat River (see the map below)

The habitats of the ancient Indo-Europeans

At the turn of the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. The First "Great Migration of Peoples" began, in which most of the Indo-Europeans took part. The tribes that inhabited the areas along both banks, that is, Italics, Greeks, Armenians, and Phrygians, most likely began their migration by water. Later the Indo-Aryans and Tochars followed them. The Thracians (Proto-Albanians) involved in this movement crossed the Dnieper and, obviously, occupied the area between the Teterev and Ros rivers. The Celts and Illyrians moved to new habitats by land. The Slavs and Balts remained in their places for the time being, while the Iranians began to occupy the abandoned areas on the left bank of the Dnieper. The Germanic tribes also significantly expanded the territory of their settlements, occupying the areas of the Greeks, Italics, Illyrians, and Celts (see map below).

At left: Ancestral homes of Germanic peoples

In these the Ethno-producing areas, primary dialects began to form, from which the ancient English, German, Gothic, Dutch, Frisian, and North Germanic languages. The authenticity of the areas is confirmed by the place names left by the speakers of these languages. In each of the areas, there are enough toponyms that are deciphered by means of one of the Germanic languages, which manifests itself quite clearly despite their similarities.

The evidence of place-names can be quite plausible in those cases when they are composed of semantically related parts with good phonetic correspondence to Old English words. For example, in Russia, there are seven settlements having the name Bibirevo, which has no convincing decoding in either Slavic, Finno-Ugric, or Turkic languages. In Old English, you can find two words that are close in meaning, the addition of which is well suited for toponymy – OE. by: "group of houses" in names of settlements (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 39) and by:re "barn", "hut", "cabin" (ibid: 40). In other cases, the decoding of play names can well correspond to natural conditions and/or historical information. Both are well answered by decoding the name of the village Dydyldino, as part of the urban settlement Vidnoye in the Leninsky district of the Moscow Region using OE dead "dead", ielde "people". The meaning of the name "dead people" is in good agreement with the existence there of a place of burial of people from ancient times. Near the village, there are burial mounds of presumably Old Russian time. In the scribe books from 1627 in the village, there was a church in the name of Elijah the Prophet which decay was noted already at that time. According to legend, at the beginning of the XV century, a female monastery was founded here by the wife of Prince Dmitry Donskoy. At the church there is the Dydyldin cemetery currently known in Moscow, about which the following information was found:

These names were assigned to the settlements by the Anglo-Saxons after they left their ancestral home in the area between the rivers Pripyat, Sluch, and Teterev and settled in the territory of modern Russia. And in their ancestral home, examples of toponyms of Anglo-Saxon origin, among others, can be:

Fenevychi, a village in Ivankiv district of Kyiv Region – OE fenn "swamp", wīc “house, village”.

Khodory, Khodorkiv, and Khodurkiv, villages in Zhitomyr Region – OE. fōdor “food, feed”.

Korosten, a city in Zhytomyr Region – OE stān "stone, rock" and the word from Cornish English care “rock ash” represented in the toponym Care-brōk (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974: 43).

Kyrdany, a village in Ovruch district of Zhytomyr Region – OE cyrten "beautiful”.

Latovnia, a river, right tributary (rt.) of the Ten’ka, rt of the Tnia, rt of the Sluch – OE latteow "leader”.

Mozyr’, a city, Belarus – OE. Maser-feld to N.Gmc. mosurr "maple" (AEW).

Naroula, a town in the Gomel Region, Belarus – OE nearu “narrow” and wæl “pool, source”.

Ovruch, a city in the Zhytomyr Region – OE of “over", rocc "rock”.

Olmany, a village in Stolin district of Brest Region, Belarus – OE oll “to insult, abuse,”mann, manna “a man” man “fault, sin”.

Prypiat’, a river, rt of the Dnieper – OE frio "free", frea “lord, god”, pytt “a hole, pool, source”.

Zherev, a river, lt of the Už, and r Žereva, lt of the Teteriv, rt of the Dnieper – O.Eng. gierwan "to boil” or "to decorate” (both meanings suit the toponyms, depending on the character of the respective river).

Zhytomyr, a city, the administrative center of Zhytomyr Region – OE. scytta “protection”, meræ “border”.

Having left their ancestral home, the Anglo-Saxons settled firstr in the Desna river basins, where they became the creators of the Sosnitsa culture. Their stay in these places was well documented by the preserved names of the rivers:

Brech, a river, lt of the Snov River, rt of the Desna – OE brec “sound, noise”.

Irpin', rt of the Dnieper – OE. ear "lake", fenn "swamp":

Iwotka, lt of the Desna – OE ea "river", wōð "nois, sound".

Nerussa, a river, lt of the Desna – OE nearu "narrow", essian "to waste". Cf. Svessa.

Resseta, rt of the Zhizdra, lt of the Oka – OE rǽs "running" (from rǽsan "to race, hurry") or rīsan "to rise" and seađ "spring, source".

Sev, lt of the Nerussa, lt of the Desna – OE seaw “sap, moisture”.

Seym, lt of the Desna – OE seam "side, seam".

Smiach, rt of the Snov, rt of the Desna – OE smieć “smoke, steam”.

Sozh, lt of the Dnieper – OE socian “to boil”.

Sviga, a river, lt of the Desna – OE swigian “to be silent”.

Swessa, lt of the Ivotka, lt of the Desna, the town of Svessa in Sumy district – OE swǽs “peculiar, pleasant, beloved”, essian "to waste".

Ul, lt of the Sev River, lt of the Nerussa, lt of the Desna – OE ule “owl”.

Volfa, lt of the Seym – OE wulf “wolf”.

Vytebet', lt of the Zhizdra River, rt of the Oka – OE wid(e) "wide", bedd "bed, river-bed".

Here and in the nearest territory of Ukraine, the Anglo-Saxons founded many of their settlements. The names of a small part of them are given below:

Bryansk (chronicle Bryn' – according Tatishchev), a city – OE bryne "fire".

Buryn’, a town, Sumy Region – OE burna “spring, source”.

Byrliwka, a village, Drabiv district, Cherkassy Region – OE byrla "body".

Dykanka, a town, Poltava Region – OE đicce "thick", anga "thorn, edge".

Ichnia, a town, Chernihiv Region – OE eacnian "to add".

Kharkov, a city – OE hearg "temple, altar, sanctuary".

Romodan, a town, Myrhorod district, Poltava Region – OE rūma "space", OE dān "humid place".

Romny, a town, Sumy Region – OE romian “to seek, aim”.

Yagotyn, a town in Kiev Region – OE iegođ "a little island".

After a long stay in Ukraine, the Anglo-Saxons migrated northeast towards Moscow. The main part of the toponyms of Russia of Anglo-Saxon origin is concentrated in Moscow, Vladimir, Yaroslavl, Tver, Vologda, Kostroma, Ivanovo, Nizhny Novgorod Regions. Here are the most convincing examples of the Anglo-Saxon place names of these places:

Berkino, villages in Moscow and Ivanovo Regions, Berkovo, a village in Vladimir Region – OE berc "birch".

Firstovo, two villages ib Nizhniy Novgorod Region and one in Moscow Region – OE fyrst "firsy".

Fundrikovo, a village, Semyonov district, Nizhny Novgorod Region – OE fundian "strive for, wish", ric "domination, government, power".

Fursovo, seven villages in Kaluga, Ryazan, Tula, and Kirov Regions – OE fyrs "furze, gorse, bramble".

Kotlas, a town in Arkhangelsk Region – OE cot "hut, cabin", læs "pasture".

Linda, a village in town district Bor, Nizhny Novgorod Region, Lindy, a village, Kineshma district, Ivanovo Region OE lind "linden".

Moscow (Moskova in chronicle), the capital of Russia, Moskva, villages in Tver and Novgorod Regions – OE mos "bog, swamp", cofa "a hut, pigsty".

Murom, a city, Vladimir Region – OE mūr wall", ōm "rust".

Ryazan, a city – 1. OE rāsian "explore, investigate". 2. OE rācian "господствовать".

Suzdal, a town, the center of the district, Vladimir Region – OE swæs "peculiar, pleasant, beloved", dale "valley". Cf. Sösdala, a locality in Sweden.

Shenkursk, a town, Arkhangelsk Region – OE scencan "to pour, give to drink, present", ūr "richness, wealth".

Yurlovo, three villages in Moscow Region – OE eorl "noble man, warrior", "earl".

This topic is considered in more detail in the sections Ancient Anglo-Saxon Place Names in Continental Europe.

The ancestral home of the Norsemen was identified in the area between the Pripyat and Berezina rivers. According to toponymy, they migrated to Scandinavia not through Finland, as one might suppose, but on the ice of the Baltic Sea from the mouth of the Western Dvina (Daugava). Place names along the banks of this river may indicate their path. They moved to the Daugava in two ways. One of them went through Minsk, and the other along the Dnieper.

The path through the city of Minsk is marked by the following place names:

Hresk, a town in Slutsk district of Minsk Rrgion – Old Norse hress "hale, bearly", hressa "to refresh, cheer".

Minsk (originelly Mensk), the capital of Belorus – Old Norse mennska "humanity", mennskr "human".

Molodechno, a city in Minsk Region – Old Norse mold "mould", ögn "chaff, husks".

Smargon', a city in Grodno Region – Old Norse smar "small", göng "lobby".

Gerviaty, a town in Astrovets district of Grodno Region – Old Norse görva, gerva "gear, apparel", tá "a path, walk".

Varniany (Vorniany?), a town in Astrovets district of Grodno Region – Old Norse varnan "warning, caution", vörn "a defence".

Svir', a village and a lake in Miadel district of Minsk Region – Old Norse svíri "the neck".

Vialikaya and Malaya Shvakshty, lakes in Postavy district of Vitebsk Region – Old Norse skvakka "to give a sound".

Svirkos, a village located on the road Švenčionys-Adutiškis in Lithuania near the border with Belarus – Old Norse svíri "the neck".

Opsa, a village and a lake in Brasla district of Vitebsk Region – Old Norse wōps "furious".

Rumische, a village in Myory district Of Vitebsk Region – Old Norse rúm "room, space".

Myory, a town in Vitebsk Region – Old Norse mjór "slim".

This topic is considered in more detail in the article North Germanic Place Names in Belorus, Baltic States, and Russia.

German place names

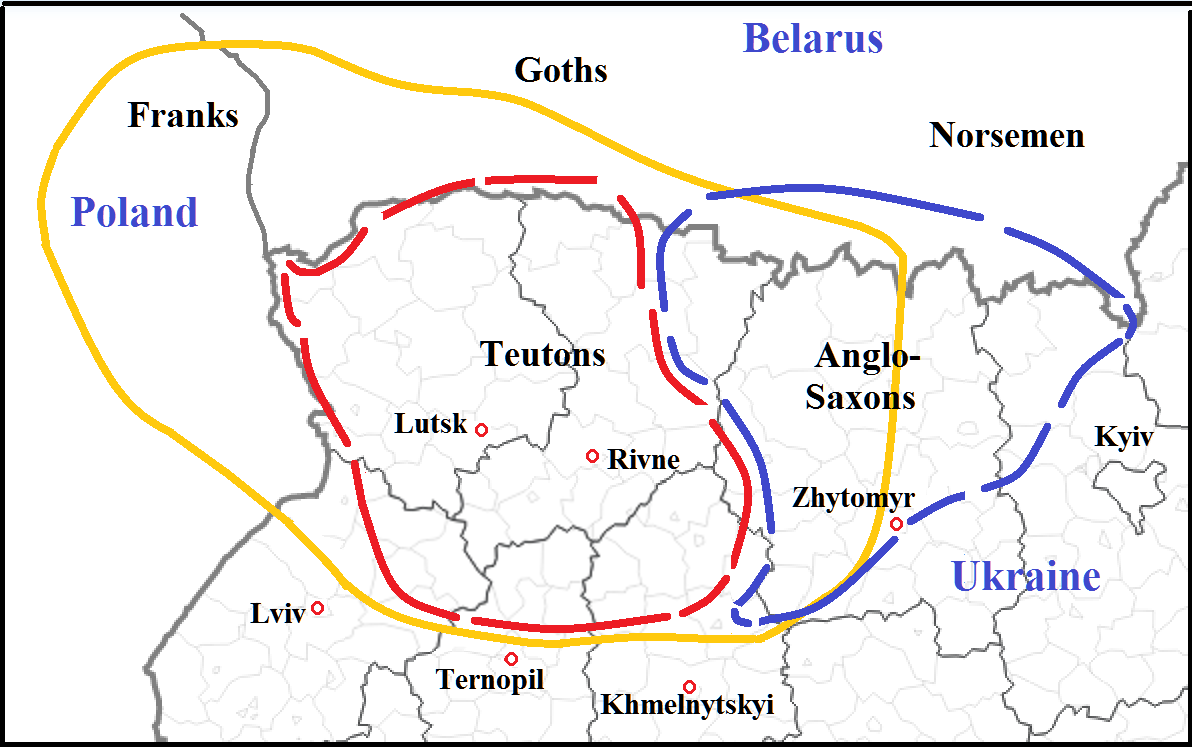

The ancestors of modern Germans, whom we conventionally call Teutons, settled in the second millennium BC. the area between the Western Bug and Sluch Rivers, south of the upper Pripyat, that is, the most part of historical Volhynia (see the map below).

Resettlement of Germanic tribes in the Pripyat basin

On the map, the approximate borders of historical Volhynia are shown with a yellow line. The ancestral home of the Teutons is marked in red, the Anglo-Saxons – in blue. Borders of regions of Ukraine are shown with black lines, regions – with gray.

The ancestral home of the Teutons is scattered across the Volyn region, most of the Rivne Region, the northern third of the Lviv and Ternopil Regions, the northern half of the Khmelnytsky Region of Ukraine, as well as part of the Pinsk and Stolin districts of the Brest region of Belarus. It was here that the deep foundations of the modern German language were laid. Like the rest of the Germanic peoples, the Teutons left traces on their ancestral homeland in onomastics that have survived to our time.

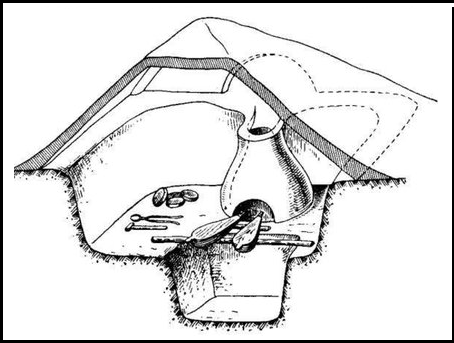

The most persuasive evidence of a Teutonic settlement in Volhynia is given by the mysterious name of the village of Velbovne in the Rivne Region. It is located on the right bank of the Horyn’ River adjacent to the historic city of Ostroh. The name consists of two ancient Germanic words: O.H.G. welb-en “to build an arch” and ovan "oven, furnace”.

At right: The scheme of bloomery.

[ZVORYKIN А.А. a.o. 1962: 69, Fig. 30].

The furnace in the form of a vault, made of stone, could be a bloomery. In this place along the right bank of the Goryn' River, the marshes stretched out for many kilometers even at present. Swamp ore is a good raw material for the iron industry. The town of Neteshin is located near to Velbovne. Its name may also have Germanic origins. For the area with metallurgical furnaces, the second part of the name can be connected with O.H.G. asca "ashes" (Ger. Asche). Accordingly, for the first part of the word, you should look for something logically related to the second one. Old Icelandic hnjođa "to forge" suits well. In the German language is present a derivative from the disappeared relative word Niete "a rivet" [KLUGE FRIEDRICH, SEEBOLD ELMAR. 1989: 504]. The bloomery produced not pure iron, but a porous mass with impurities of sulfur, phosphorus, and other metals and slag. To produce iron, this bloom must be re-forged, when the impurities were separated as ash [ZVORYKIN А.А. a.o. 1962: 68]. Thus, there was a specialization – the bloom was produced in Velbovne, and it was converted to more or less pure iron in Neteshin.

In the ancestral home of the Teutons, there are more than ten toponyms containing the word "Huta". This word is present in the Ukrainian language and it means "smeltery". It is present also both in the Russian and Belarusian languages. There are about eight dozen such place names in Eastern Europe. It is very doubtful whether they are all of the Slavic origins. Since they are in the overwhelming majority located on the common German territory or along the migration routes of Germanic tribes among other place names of Germanic origin, it should be admitted that they mainly descend from OHG of Old Saxon hutta "hut, cabin". Only a small part of such toponyms may have Slavic origin since the craft of glass or metal smelters was not so widespread among the Slavs. However, it is practically impossible to distinguish them, therefore all toponyms of this type are highlighted in a paler color.

We now look at several other examples of place names that have no compelling definition by means of the Slavic languages, but which can be etymologized on the basis of German:

The village of Farinky, east of the town of Kamin' Kashirsky, Volyn Region – O.H.G. faran "to drive, go” -ing is a noun suffix.

The village of Fusiv in Sokal district, Lviv Region – Ger Fuß, O.H.G. fuoz “foot”.

The town of Kiwertsi, Volyn Region – Ger. Kiefer, M.H.G. kiver, "jaw, chin".

The city of Kowel, Volyn Region – Ger. Kabel “fat, lot”, M.H.G. kavel-en – "to draw lots".

The village of Newel, southwest of the city of Pinsk (Belarus) – Ger. Nebel, M.H.G nebel, OE neowol "fog".

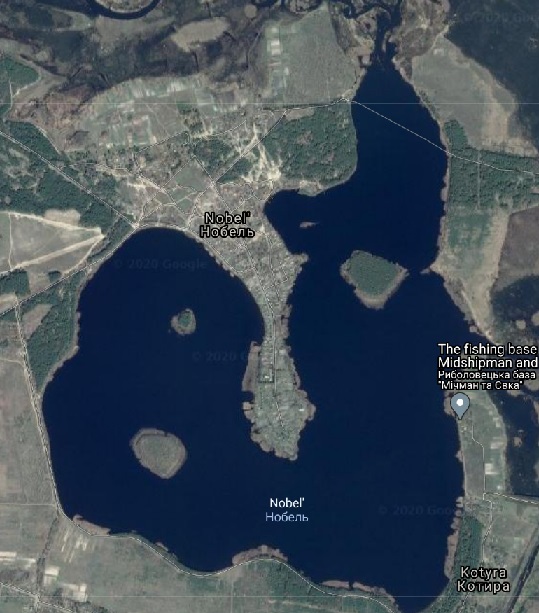

Lake Nobel and the village of Nobel, located west of the urban-type settlement of Zarične in Rivno Region on a peninsula of the lake – Ger. Nabel, O.H.G. nabalo, “navel”.

At left: Lake Nobel. Satellite photo.

The town of Radekhiv, Lviv Region – Ger Rad, O.H.G. (h)rad “wheel”, Ger. Achse, O.H.G. ahsa “axle”.

The town of Radywiliv, Rivne Region – Ger Rad, O.H.G. (h)rad “wheel”, Ger. übel, O.H.G. ubil – “evil”.

The village of Rastow, west of the town of Turiys’k, Volyn Region – O.H.G. rasta, "stay".

The village of Reklynets in Sokal district, Lviv Region – Ger. rekel “a big he-dog”.

The Styr River, the tributary of the Pripjat’ – Ger. Stör, O.H.G. stür(e), "sturgeon”.

The Strypa River, the tributary of the Dnister, which spring lies on the border of the Teuton area – M.N.G. strīpe “a stripe”. However, the name can have an Anglo-Saxon origin.

The village of Tsehiw in Horokhiv district, Volyn Region – M.H.G. zæh(e) "viscous, tough".

The village of Tsuman', to east of the town of Kivertsi – Ger. zu Mann “to a man”.

The Tsyr River and the village of Tsyr – Ger. Zier, "decoration”, OHG zieri "good”.

These examples list of names of Teutonic origin in Volhynia may not be exhaustive, but some place names in the northern part of the area could also have an Old Dutch origin. For convenience, we will call the ancient Dutch people here Franks. Together with the Frisians, they occupied the most western area of the entire Germanic territory. This territory is bounded by the San and Vistula Rivers in the west, the Neman River in the north, the Yaselda River in the northeast, and the upper reaches of the Pripyat River in the southeast. It borders with the Teutonic area near Lakes Shatski. There is an accumulation of names here, which can have both Teutonic or Frankish origin. The very name of the lakes is best deciphered by the German languages (OHG scaz, "money, cattle", Ger. Schatz "treasure", Dt. schat "the same"). We can also speak about the Teutonic origin of the names of the village of Pulemets and Lake Pulemetske. They can be deciphered as "the full measure of grain" (Ger. volle Metze, OHG fulle mezza – EWDS). A fancy name of another lake Lyutsemer can be understood as the "little sea" (Ger. lütt, lütz, OHG luzzil "little", mer, Ger. Meer "sea"). Words similar to the mentioned exist sometimes in other Germanic languages, but the transition of Germanic t in z, being present here, is characteristic only of the High German language. At the same time, the name of Lake Svityaz belongs better to the Dutch language, as Gmc *hweits "white" corresponds better Dt. wit and just its pre-form *hwit could naturally transform to Svityaz in the Slavic languages (Gmc. -ing, -ung corresponds always Slav -iaz'). For OHG. (h)wīz "white", it seems unreal.

The migration routes of the Teutons and Franks to Central Europe passed through the territory of Poland and on it, they had to leave their traces in toponymy. Many place names can be interpreted in both German and Dutch. When plotting on the map, their relative positions were considered; those located south of the Dutch were classified as German. In general, there are a lot of geographical names of German origin in Poland, but it is difficult to single out the most ancient ones, because many place names may date back to later times.

Germanic Onomastics in Eastern Europe

On the map, settlements are indicated by asterisks.

Different colors on the map correspond to the different ethnicity of the symbols.

The red corresponds to Teutons, the brown to Norsemen, the orange to Anglo-Saxons,

the blue to Franks, the Green to Goths.

Place names are marked with asterisks, ancestral homelands – filled.

The dots mark the settlements in which the surnames of Germanic origin are recorded.

Place names of Huta are colored in lighter colors.

Frankish place names

Obviously, the Western Bug River divided the Franks and Frisians in the indicated above area. A Frisian dictionary of a large amount was absent for services, so we will restrict the search only by names that can have a Frankish origin. Using the Dutch language, we can talk about such possible Frankish place names:

Brok, a town in Ostrów Mazowiecka County, Masovian Voivodeship and a village in the administrative district of Gmina Wysokie Mazowieckie, within Wysokie Mazowieckie County, Podlaskie Voivodeship – Dt. broek, M.Dt. brōk “humid lowland”;

Western Bug, rt of the Vistula River – M. Vasmer considers the possibility of the Germanic origin of the name of the Western Bug, but does not give Dutch words [VASMER M. 1964: 227]. Meanwhile, M.Dt. bugen (Dt. buigen) "to bend" fits well (the Western Bug River is very winding);

Garwolin, a village in Masovian Voivodeship – Dt. garwe, garf “sheaf”, lijn “flax”;

Kobryn, a town in Belarus – Dt. kobber “he-pigeon”;

Kodeń, a village on the banks of the Western Bug River in Poland – Dt. kodde “sack, bag”;

Kujawy, a village in Masovian Voivodeship – Dt. kuif “a crest”;

Malorita (Malaryta), a town in the Brest region – the town could have been called Malaya (Small) Rita, since it is located on the small river Rita, the name of which can be associated with ODt. rith "flood, spill" (OE riđ) "stream").

Wagan, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Tłuszcz, within Wołomin County, Masovian Voivodeship – Dt. wagen “a car”;

Worsy, a village in Lublin Voivodeship – Dt. vors “frog”;

On the territory of Poland there are several toponyms containing the word rus in the first part of the name: Rusinowo, Rusiec, Rusia, Rusek, Rusocin, Rusinow, Rusocice. They have nothing to do with Russians and Russia. They can come from the floor. rusy "light brown". A similar word is found in all Slavic languages, but in none of the Slavic countries is there such a cluster of toponyms derived from this word, as is the case in Poland. True, the two villages of Rusinów in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship should be named after the Ukrainians who settled there, who were called Ruthenians in Poland. More than a dozen place names of Rusinovo are located among the Anglo-Saxon ones, but the word rus has not been found in Old English. It makes no sense to name villages among Russians by their Russian population. Perhaps they come from the word blond. Some of the above Polish place names are located west of the ancestral home of the Franks. The second part is located among Gothic place names and is woven into the chain that leads from the ancestral home of the Goths to Danzig. It can be assumed that the first part of these toponyms comes from ODt. rus having a complex origin (VEEN P.A.F. van, SIJS NICOLINE van der, 1997: 761). In Flanders there are many place names with the word rus or ros. Luke Vanbrabant associates the chronicle Rus with the same word. Explaining its origin and meaning, Luke Vanbrabant writes

The meaning always comes down to reed or rush. That is why I call the rus (ros, rose, ruis, reus, etc.) as people of the reeds, and ruskere as a reed dweller. (Reus [røs] has a homonym which means giant.) By extension, that name may also have been used for the activities those people performed from the reeds and even for some physical characteristics. In the tenth century, according to Dave De Ruysscher (see below), the name rus was a common name for a skipper and seafarer. (VANBRABANT LUC. 2024: 4).

The etymological dictionary of the Gothic language also considers the word *rus, but it is assumed that it comes from the root rust (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1934: 83). The ancestral home of the Gotos, as well as the Dutch, was in a swampy area overgrown with reeds, therefore in the Gothic language the word rus meant “reeds” too.

Vanbrabant repeats the idea of Omelyan Pritsak about the Western European origin of the Rus people (PRITSAK OMELJANn. 1977) and clarifies that his language was one of the dialects of Flemish. He cites many place names like rus/ros in Belgium and several in neighboring areas of France and the Netherlands. However, the movement of the Franks from their ancestral home to their places of permanent residence should have left its traces in toponymy in Poland and Germany. These traces are still preserved in these and neighboring countries. These have been mapped onto Google My Maps (see below).

Place names like rus/ros

Gothic place names

The area of the formation of the Gothic language because of the scarcity of available lexicon was localized only conceived. A suitable place was found on both sides of the Schara River, left tributary of the Niemen River, i.e. where was the common Urheimat of all Germanic people. The name of this river should be considered as the Paleo-European substrate, which traces can be found in some Germanic languages, cf. Eng. shore, Ger. Schaar "area of the sea, where you can wade". Confirmation that the Gothic language began to form precisely here, is given by local toponymy. When their deciphering F. Holthausen's Gothic Dictionary and partly Dictionary of the Icelandic Language as the closest to the Gothic were used. The following are examples of possible place names in Belarus:

Abrova, a village in Ivatsevich districk of Brest Region – Got. *abr-s "strong, stormy".

Alba, a village in Brest Region, Belarus – Got.*alb-s "a demon".

Bastyn', a village in Lunenets district of Brest Region – the all modern Germanic languages have the word bast "bast, the inner bark of the lime-tree" (Old Norse, Dt. bast, OE. bæst, Ger. Bast). Undoubtedly, this word was present in the Gothic language, but not preserved in written sources referring to specific meaning.

Indura, a village in the Grodno district of the Grodno Region – Got. in daurō "at the gate".

Odelsk (Adel'sk), an agro town located in Grodno district in Grodno Region – Got. ōþal "inheritance".

Rumliovo, a forest park in the city of Grodno – Got.rūm "room, space", lēw "a case".

Trabovychy, a village in Lakhovychy districkt of Brest Region – Got *draibjan "to drive".

Vangi, a village в Grodno Region, Belarus – Old Norse vang-r "a garden, green home-field".

Velikie Eysmonty, a village in the Byerastavitsa district of Grodno Region – Got. eis "ice", munþ "mouth".

Zelva, the center of district in Grodno Region – Got. silba, Old Fr. selva "self".

There are on the Urheimat of the Goths a few place names, which could be deciphered by other Germanic languages (Gresk, Narev, Rekliovtsy), the Gothic language has or maybe had similar words, therefore it is difficult to judge about their origin. The most frequently is mentioned place name Huta (five or six cases). However, the Gothic language did not record the word hutta in the meaning of "hut". One can only assume that such a word existed in it, therefore the place names Huta are nevertheless marked in the ancestral home of the Goths .

Gothic place names in Eastern Pomerania

If traces of the Goths remain in the place toponymy on their ancestral home, then all the more Gothic place names must be preserved in places of their later residence. Clearly, the search began in neighboring areas, that is, in eastern Poland, and quickly has succeeded. Gothic place-names formed a chain which led to the city of Danzig:

Kundzin, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Sokółka, within Sokółka County, Podlaskie Voivodeship – Goth. kunþi "relationship, home".

Chilmony, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Nowy Dwór, within Sokółka County, Podlaskie Voivodeship – Goth. hilm "helmet".

Fasty, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Dobrzyniewo Duże, within Białystok County, Podlaskie Voivodeship – Goth. fastan "hold, guard".

Sajno, lakes in Augustów County of Podlaskie Voivodeship and in Pisz County of Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, – Goth. sainjan "to tarry, hesitate".

Ełk (previous Łek), a town in Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship – Goth. leik "bode".

Ukta, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Ruciane-Nida, within Pisz County, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship – Goth. ūhtwō "dawn".

Wałdyki, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Lubawa, within Iława County, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship – Goth. waldan "prevail, govern".

Markowo, villages in Gmina Dubeninki, within Gołdap County and Gmina Morąg, within Ostróda County Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship; – Goth. marka "sigh", "border'.

Gruta, a village in Grudziądz County, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship – Goth. grūts "grain".

Wandowo, a village in Kwidzyn County in Pomeranian Voivodeship – Goth. wandjan "tp turn".

Kaldowo, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Malbork, within Malbork County, Pomeranian Voivodeship – Goth. kald-s "cold".

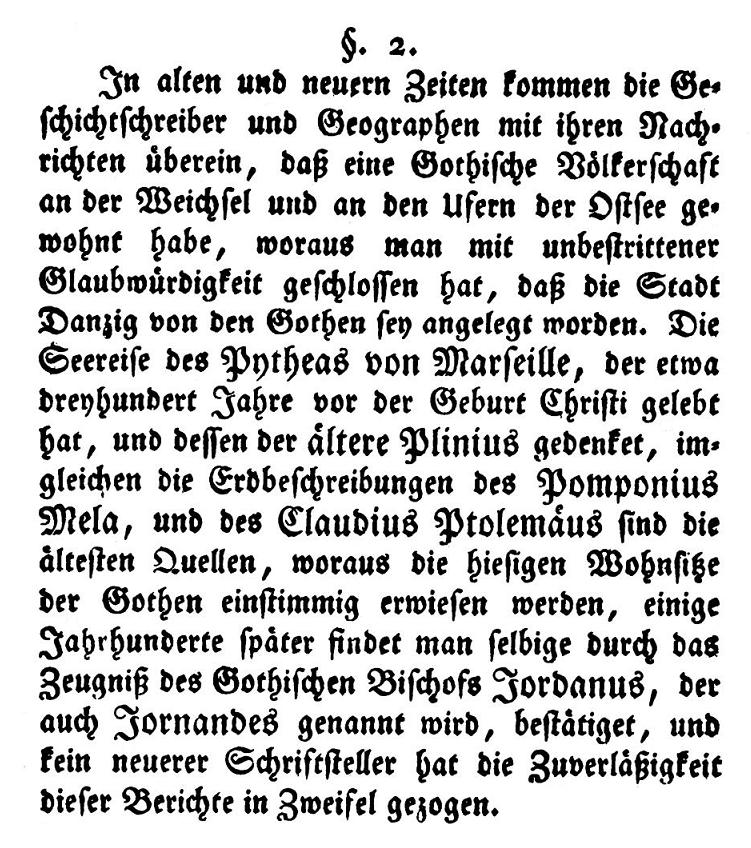

To decode the name of the city of Danzig failed, but it was found evidence that the city was founded by the Goths (see the image below)

The image is a copy of the page from the book of Daniel Gralath "The try of a story of Danzig on reliable sources and manuscripts" (GRALATH DANIEL, 1789: 4). The copy is made out of a book of the Library of Chicago University, posted on the Internet. Translation of the text from German:

As in old and in new times, historians and geographers are unanimous in their reports, concluded that the Gothic nation dwelled along the Vistula River and on the banks of the Baltic Sea, which from one can conclude with unquestionable certainty that the city of Danzig was founded by the Goths. Voyage of Pytheas from Marseilles, who lived three centuries before the birth of Christ, and who is mentioned by Pliny the Elder, and also geographies of Pomponius Mela and Claudius Ptolemy being the most ancient sources, clearly indicate the settlements of the Goths here, and some later several we find the same evidence from the Gothic Bishop Jordanes, also called Jornandes, who this confirms, and no historian has questioned all these messages.

Further Gralath Daniel as so long-winded interprets the evidence of Jordanes, that Danzig (ie Gdansk) was founded by Gothic king Berich and disputes other versions. The fact, that the message of Jordanes is something contradictory, he argued that the Gothic king came on three ships at the mouth of the Vistula from Skancia (Scandinavia), and the founded city named Gothenschanz (or Gothiscanzia), i.e. "Gothic trenches". And supposedly the name was gradually transformed into Danzig, apparently through an intermediate form of Gdańsk, preserved in the Polish language. The arrival of Goths from Scandinavia is contradicted by place names data, according to which the Goths came to Pomerania from the banks of the Neman and Pripyat Rivers.

Supporters of the Norman theory argue that the Rus should be understood as the Swedes, but this was not their self-name. Therefore, they believe the word rus comes from Finn ruotsi because that’s what the Finns call the Swedes. This word supposedly comes from Old Sw. rōþs, etymologically related to the verb meaning “to row” (HÄKKINEN KAISA. 2007, 1073). However, this name for the Swedes could only arise if the Finns themselves did not engage in rowing and had no own word for such an activity, which is very doubtful. Realizing this, Häkkinen explains the Finnish name for the Swedes through the name of a small region in Sweden, which does not seem convincing.

This enigma is resolved if we agree that the Rus were the Flemings, who collaborated in their trade operations with the Swedes, as Pritsak writes in detail in the mentioned work. In the chronicles, the Swedes appear under the names of Rus' and Varangians, but only the last word applies to the Swedes, and by Rus' only the Flemings should be understood. Based on the above, ruotsi is not of Swedish origin but comes from Goth. rauþs “red”, as the Goths could call red-bearded people.

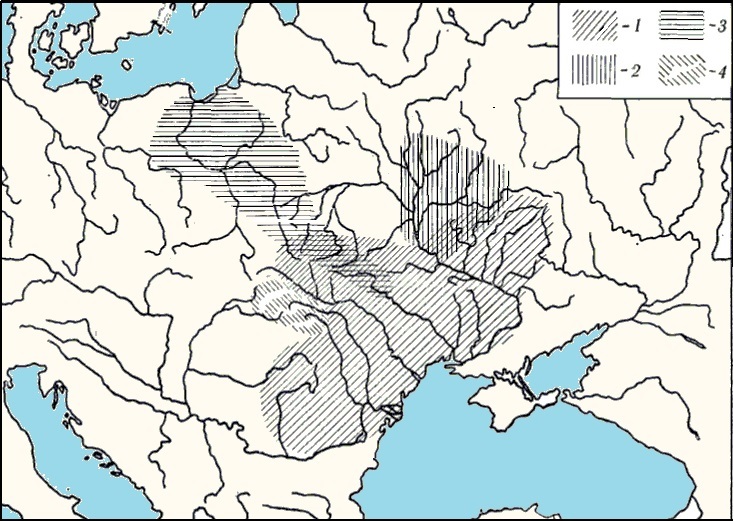

Most likely, the Goths called the red-bearded Swedes red, and this word came to the Finns from them at a time when the Goths could be both neighbors of the Finns and the Swedes. The Finns, and after them the Slavs, used the same word to call Flemish Rus'. They could not clearly distinguish between Swedes and Flemings without distinguishing between Germanic languages. The Gothic influence is explained by the fact that there was communication between Pomerania and Scandinavia, some of the Goths could remain there for a permanent or temporary settlement, and then return. The name of the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea speaks about this. However, archaeological sources also do not agree with written information, which caused lengthy discussions (BIRBRAUER F. 1995, 32). The Wielbar culture is associated with the Goths, on whose territory Gothic place names were found (see maps below).

Left: Gothic place names in the Gdansk area. Right: Sites of Wielbark culture in the B1 phase (BIRBRAUER F. 1995, 34. Fig. 4, according: WOŁĄGIEWICZ R. 1986. Stan badań nad okresem rzymskim na Pomorzu).

Goths appear in the Northern Black Sea region in the 2nd century. AD and they play a major role in creating the Chernyakhov culture, whose early monuments are in the regions of Western Ukraine (BARAN V.D. 1985: 47). A strip of Wielbark sites also goes there (see the map below), which suggests the development of Chernyakhiv culture on its basis. However, despite the fact that the Wielbark sites or elements of this culture stand out among Chernyakhiv ones in all regions, the complete transformation of the Wielbark culture into Chernyakhiv is questioned (ibid 1985, 74). Archaeologists cannot agree on whether the features of pottery, common to the Wielbark, and Chernyakhov cultures, are the main ethnic trait (VAKULENKO L.V. 2002: 18).

The area of archaeological cultures of the second quarter of the 1st mill. AD.

Legend: 1 – Chernyakhiv, 2 – Kyiv, 3 – Wielbark, 4 – Carpathian Tumuli culture (BARAN V.L. 1985: 46, Fig. 8).

One can agree that the formation of Chernyakhiv culture was influenced by various factors, but it should be noted that the role of the Slavs in this process is overestimated from the false assumption that they lived in the Lower Dnieper before the Goths. One can speak more confidently about the Alanian influence since the Alans were also one of the Germanic tribes. Nevertheless, it seems obvious that the carriers of both the Chernyakhiv and Wielbark cultures were mainly the Goths, even without much attention to the similarity of the pottery of these cultures.

Germanic anthroponymy

During the research, some traces of the stay of the ancient Germans in Eastern Europe were also found in anthroponymy. This gave impetus to systematic searches, which so far are being maid only in Ukraine and Poland using the " Map of the dissemination of surnames in Ukraine" and the database of Polish surnames, available on the Internet. First of all, searches were carried out in the ancestral home of the Teutons. The correspondence of the surnames of the alleged Teutonic origin to the Old German words was checked using the etymological dictionary of the German language (KLUGE FRIEDRICH. 1989).

The most convincing evidence of the stay of the ancient Germans in Eastern Europe is a cluster of surnames on th basis of the root shym (shem): Shymko (3818 carriers in Ukraine), Shemchuk (1590), Shymkiv (1099), Shymchuk (1068), Shymchenko (435), Shymanovych (250), Shymchyshyn (157), Shymkovich (146), Shymka (108), Shymchyk (97), Shymchak (77) and others, less common. The origin of the surname from the Slavic root is excluded, it should be deduced from Gmc. skeim-a and the primary basis of the entire cluster was the name Shyma (now there are 41 carriers of this surname in Ukraine). The surname Shymko is fairly evenly disseminated in the western and northern regions. In Volhynia, it can come from OHG. scīmo "ray, shine", and in the more eastern regions from OE. scīma "ray, light, shine". The surname Shymchuk is found everywhere in Volyn Region (in the Kovel district there are 31 carriers, in Vladimir-Volynsky – 29, in Kivertsevsky – 28, in Lyubomlsky – 17, etc). Nearby, in the Krasilovsky district of the Khmelnytsky Region, 55 carriers have this surname, but in most districts of the Region, it took the form Shemchuk (in Krasilovsky district- 60 carriers, Shepetovsky – 58, Izyaslavsky – 56, Teofipolsky – 39). In the Ovruch district of the Zhytomyr Region, in the ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons, 40 residents have the name Shymchuk. In Poland, the surname Szyma is recorded for 560 people, with 473 carriers living in the southern Malopolskie and Silesian Voivodeships (in Katowice – 70 carriers, Czestochowa 55, etc.). It is difficult to say whether the surnames Shyman, Shymansky, Shemansky belong to this cluster.

It is significant that the surnames Schima and Schime are absent in the alphabetical list of German surnames, and the surnames Schimke and Schmko (1580 carriers) are considered to be Slavic, derived from the name Simon.

No less convincing is the Pro-Germanic origin of the surname Smal (3315 carriers in Ukraine and about 200 in Poland), although at first glance it may also have a Slavic origin. In fact, it is the reflex of Gmc *smala- "small". Currently, more than two thousand carriers of this surname live mainly in Volhynia and in the adjacent districts of the Lviv Region, and phonetically this anthroponym corresponds very well to OHG smal "narrow, small". True, most of the carriers of this surname lives in Kyiv (140), but this is a consequence not only of later migrations of Ukrainians, but also the location of the Anglo-Saxon ancestral home nearby, and in Old English, there was also the word smal "small". There are also many carriers of this surname in Kharkiv (133) and in the Kulykivsky district of the Chernihiv Region (81). This fact testifies to the resettlement of the Anglo-Saxons to the left bank of the Dnieper. In the ancestral home of the Teutons, large numbers of carriers of this surname were recorded in Kovel (112), in Radekhiv (149), Sokal (74), Brody (42) districts of the Lviv Region, and in such districts of the Volyn Region: Ivanychi (106), Horokhiv (99), Kovel (77 without the city of Kovel), Lyubeshiv (76), Kamen-Kashirsky (64), Rozhische (28), Starovizhevsky (23) and others but in smaller quantities. In Poland, most of the carriers of the surname Smal are in the town of Skarżysko-Kamienna of Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (27) and in the city of Zielona Góra in Lubusz Voivodeship (27).

The opinion is erroneous that the Ukrainian surnames Stetsenko (12911 carriers), Stetsyuk (8789), Stets (3798), Stetsyk (1569), Stetsyura (1374), Stetsko (1325), Stetsiv (806), Stetsishin (743), Stetskiv (484), etc descended from the name Stepan. In fact, they are based on Gmc root *stek-a, derived from which, a semantic field was formed in the meanings "to stab, pierce, stick, stake, rod, etc.". In the Ukrainian language, during word-formation, this root took the form stets and from it more than fifty different Ukrainian surnames were formed. In Polish, the Germanic root took the form stec and from it, more than three dozen different surnames were formed. Stec is the most common of these, 9617 Polish citizens have it . Now it is widespread throughout the country, but most of all in the southern voivodeships on the path of movement of Germanic tribes to the west (Kraków – 285 carriers, Stalowa Wola – 276, Rzeszów – 195, Lublin -169, etc.) The surname Steć is often found in Poland too (1512 carriers). Although the surname is widespread throughout the country, a third of its carriers live in the Lublin Voivodeship, which borders Western Ukraine. Without a doubt, most of the carriers of this surname are ethnic Ukrainians or their ancestors. The same can be said about the surname Steciuk (516 carriers). Such surnames can be typically Polish: Stecki (922 carriers), Steckiewycz (785), Stecyk (441), Stecura (92), Stecewycz (77), Steckowski (27) and many others with less carriers.

The surname Stetsyuk is most common in the Rivne Region, namely in Kostopolsky (203), Zdolbunovsky (115) districts, in the regional center (188), as well as in the neighboring Kremenetsky district of the Ternopil Region. (254 carriers), that is, in the ancestral home of the Teutons. One might think that the surname comes from OHG stecko "stake, club". The presence of carriers of this surname in slightly smaller numbers in the neighboring districts of the Khmelnytsky Region and in Khmelnytsky itself (236 carriers) is explained by migrations of historical times, while the surname Stetsyuk (520 carriers) common in Kyiv may come from OE. steсca "stick". The surnames Stets, Stetsyk, Stetsiv, Stetsishin are also more common in Western Ukraine.

The concentration of the surname Burko is characteristic in Volhynia out of the total number of its carriers in Ukraine (1558). It has a correspondence in OHG burg "settlement, burg". In Sokalsky, Zhovkivsky districts of the Lviv region, and in the Ratnovsky district of the Volyn Region, there were 110, 73, 88 carriers of this name, respectively. Also, this surname is present in Vinnytsia, Kyiv, Kharkiv as evidence of the presence of the Anglo-Saxons in those places (OE burg). However, this surname may also have a Slavic origin, although in Volyn the surname Bury is found only in isolated cases. In etymological dictionaries, the word buryi "brown" does not refer to the Proto-Slavic and is considered a possible borrowing from the Turkic of later times. In Poland, there are many carriers of surnames containing the root burg, but only a small part of them can exist for a long time. These are mainly German surnames of modern times.

In the same way, out of 1176 carriers of the surname Shakh in Ukraine, most of them live in Volyn or in their immediate surroundings (in Dubrovitsky district of Rivne Region -74 carriers, Yavorivsky district of Lviv Region -68, the city of Rivne – 57); in Poland, there are 216 carriers of the surname Szach, mainly in the southern and western provinces – OHG. scāh "robbery".

The surnames Shur and Shura are prevalent in Volyn (about two hundred speakers out of a total of 478 in Ukraine); there are significantly more carriers of such surnames in Poland (1785 people have the surname Szura, of which 1130 live in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, and about 150 carriers of the surname Szur) – OHG skūr, "storm, downpour", OE. scūr, scūra "the same".

The presence of the Anglo-Saxons in the Dnieper region was mentioned above, and Vinnytsia marks their way to Western Europe. The name of this city can be associated with OE. winn "work, effort, victory". Like this word, OHG winnan and Ger. gewinnan "achieve success through efforts" originated out of the Germanic root wenn-a "to work, to strain". The surname Vinnik, which is found in Volyn (there are 40 carriers in the Rozhischensky district and 29 in the Rivne district), should come from these German words. A very similar surname Vinnyk, common in the East of Ukraine, which in Russian is also transliterated as Vinnik, may be of the Anglo-Saxon origin or be a reflex of a Slavic root (compare wino "wine", wina "guilt"). The same can be said about Poland, where most of the carriers of the surname Winnik, excluding Warsaw (134 carriers), live in the south of the country along the path of the Anglo-Saxons to the west (Lower Silesian Voivodeship – 230 carriers, Silesian Voivodeship – 162).

In Poland, the surname Szych is quite common (1048 carriers). It, together with its corresponding Ukrainian Shykh (285 carriers), can be compared with the MHG schiuhen "be afraid". In Poland, the surname is found evenly throughout the country, and in Ukraine – mainly in the Lviv region (227 carriers).

Obviously, in Volyn there are other surnames of Teutonic origin, but in small numbers. These can be, for example, Khvishchuk (121 carriers) and Khvits (60), which can be associated with OHG. fisc "fish", Hihera (41) – OHG hehara "jay, magpie, jackdaw", Humel'a (12) – MHG homele "hop".

There are more convincing traces of the stay of the Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe in anthroponymy to our time than the Teutonic ones because the Anglo-Saxons inhabited a much larger territory for and much longer than the Teutons. At the same time, a significant part of Anglo-Saxon anthroponyms stretched out in a chain along with the same places along which a strip of place names of alleged Anglo-Saxon origin stretches, which marks the path of migration of the Anglo-Saxons to the west. Germanic roots are found in both Old High German and Old English and Old Saxon, and the Anglo-Saxons followed the same path that the Teutons laid before them. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the exact ethnicity of Germanic anthroponyms, but it is significant that the concentration of their part corresponds well to the accumulation of Gothic and, to a lesser extent, Frankish place names. Germanic anthroponyms in Eastern Ukraine can only belong to the Anglo-Saxons, but they are also present in settlements along the path of the Anglo-Saxons to the west. Here are some of them:

Stetsenko, 12911 carriers in Ukraine, exclusively Ukrainian surname by origin, disseminated mainly in Central and Eastern Ukraine. Most of all carriers live in Kiev (1461 carriers), Kharkiv (568), Sumy (293), Kryvyi Rih (273), Zaporizhzhia (237), Dnipro (215), Khorol district of Poltava Region (149), Radomyshl district of Zhytomyr Region, in the city of Chernihiv (103) – OE. steсca "stick".

In Poland, there are 5436 carriers of the surname Szot, most of all in the south of the country (together in the Małopolskie and Silesian Voivodeships 2660); in Ukraine, 575 the surname Shot has 575 carriers, most of all in Yavorivsky (153), Mostysky (80), and Zhovkivsky (37) districts of Lviv Region – OE scot "shot, fast movement".

Statsenko, also a Ukrainian surname, 2148 carriers, most of all in Zaporizhzhia (95), Kyiv (89), Dnipro (60), Donetsk (50), Karkiv (46) – OE. staca "post, stake".

Stetsyura, 1374 carriers in Ukraine, most of all in the Nemirovsky district of the Vinnytsia Region (125), Kyiv (77), Vinnytsia (53), Krasnokutsk district of Kharkov Region (44), Sumy (40), Kharkiv (34), Belopolsky district Sumy Region (32), Artemovskiy district of Donetsk Region (25) – OE steсca "stick".

Brytan, 859 carriers in Ukraine, most of all in the Petropavlovsk district of the Dnepropetrovsk Region (75), in the town of Yavoruv in Lvuv Region (60), Cherinihiv district (45); in Poland there are 265 carriers of the surname Brytan, most of all in the town of Myślenice of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship in the south of the country (43) – OE. brytan "destroy, break".

Grama, 551 carriers in Ukraine, most of all in the Sokiryansky district of the Chernivetsky Region (54), Kyiv (52), Polonsky district of Khmelnitsky Region (43), Obukhiv district of Kyiv Region (34), Ruzhinsky district of Zhytomyr Region (33), Belopolsky district of Sumy Region (18), Alexandria district of Kirovograd Region (15), Shpolyansky (12) and Khristinovsky districts of Cherkasy Region; in Poland there are carriers of the surname Gram in small numbers – OE. grama "enemy".

Tusk, 526 carriers in Poland, most of all in Pomeranian Voivodeship (464); there are surnames Tuskevych (14 carriers) and Туско (6) in Ukraine, all in east – OE. tūsc "canine, tusc".

Smal', of the total number of carriers of this surname (3315), about 500 may have a surname of Anglo-Saxon origin, most of all in Kiev (140), Kharkov (133), Kulikovsky district of Chernihiv region. (81) – OE smæll "narrow, small".

In the north and south of Poland, 398 carriers of the surname Salik were recorded; in the south, this surname may originate from – OE. sælig "happy" and north of similar Gothic; in Ukraine, the surname Salyk can belong 282 people, most of all in Tulchinsky district (42) of Vinnytsia Region, Yavorivsky district of Lviv Region (35), Gusyatinsky district, Ternopil region (28)

Lempa, in Poland 372 carriers, most of all in the Silesian Voivodeship (301), in Ukraine 44 carriers – this surname can be associated with OE lempihealt "lame" (English limp, OE healt "lame").

Shokh, 337 carriers in Ukraine, most of all in Kyiv (66 carriers), Chernihiv (30), Tetiyiv district of Kyiv Region (29), in the city of Smila in Cherkasy Region (23), in Poland 86 carriers of the surname Szoch – OE sceoh "cowardly".

Shal'ko, 270 carriers in Ukraine, most of all in Chigirinsky district of Cherkasy Region (14), Zhovkva district of Lviv Region (13); in Poland, the surname Szalka is most widespread in the Podkarpackie Voivodeship (43 carriers) out of a total of 51, the surname Szalko – mainly in the east (38 speakers) – OE. scealg "servant, squire"; 82 people have the surname Szalk, of which 80 live in the Pomeranian Voivodeship – Goth. skalk-s "same".

Pritsak, 149 carriers, most of all in Drohobych district of Lviv Region (80) – OE. prica "point, prick, spot".

Birko, 134 carriers in Ukraine, most of all in Dnipropetrovsk and Kirovograd Regions (more than 100) – OE. bierce "birch".

Undoubtedly, there are other surnames of Anglo-Saxon origin in Eastern Europe, but in smaller numbers. Such can be, for example, Ronik (45 carriers) – OE reonig "sad", Mitsel'a (24), Mitsel' (19) – OE. micel "strong"; Vitol' (19) witoll "wise"; Rempa (11) – OE. rempan "hurry".

Conclusion

The obtained onomastic data of Germanic origin, testifying to the presence of the ancient Germans in Eastern Europe, raises the question of the time and duration of their stay in the places of their original settlement.

We know that the ancient Germans occupied the territory from the Vistula to the Dnieper on both sides of the Pripyat. Here they became the creators of the most ancient version of the Trzciniec culture, which later spread in different versions to the Oder in the west and to the Desna in the east. The eastern massif of the Trzciniec Cultural Circle can be dated back to the period 1700 – 1000. BC. (LYSENKO S.D. 2005: 60). Thus, one can think that the Germans began to migrate westward in the middle of the second millennium BC. It is difficult to say how massive this movement was, but, as always happens with the resettlement of peoples, some part of the Germans remained for some time in the old places of the settlement.

The reasons that forced the Germans to leave their ancestral home may be different, but one of them should have been the pressure of the Balts, who began to migrate in different directions, including to the south, to the Germanic lands (see the section Ancient Balts Outside Ethnic Territories). The newcomers established their settlements in suitable places or settled in existing ones, if the indigenous people allowed them, which was possible with their small number. This is how the process of assimilation of the Germans among the Balts began. At the same time, on the basis of the Trzciniec culture, a new one developed here, known as Milograd, which supposedly existed in the 7th – 1st centuries. BC, although its earlier origin is possible (LYSENKO S.D. 2012: 271). Obviously, a three-hundred-year period from the end of the XI cen. BC was filled with clarifications of the relationship of the Balts with the remnants of the Teutons.

At the beginning of the III century BC. in the upper reaches of the Pripyat, the Slavs appear and eventually populate the Middle Dnieper basin, becoming the creators of the Zarubinets culture (III / II century BC – II century AD). A Slavic tribe of Dulebs (Dudlebs) was formed in Volyn. The name of this tribe has been preserved in several toponyms of Western Ukraine and the Czech Republic, and according to some scholars, this ethnonym comes from West Germanic Deudo– and laifs [MELNYCHUK O.S. (Ed.) 1982-2004. Vol. 2.: 144; VASMER M. 1964-1973. Vol.: 551]. The first part of the word means “Teutons” and from it comes the self-name of modern Germans Deutsch (OHG diot "people"), and the second – “remnant” (OHG laiba). Thus, the word Dulebs can be translated as “remnants of the Teutons”, which gives grounds to say that some part of the Teutons remained in Volyn before the arrival of the Slavs there. In the process of the disintegration of the Proto-Slavic language, a dialect was formed here, which gave rise to the Czech language (see the section The Ethnogenesis of the Slavs. Evidence of the presence of the ancestors of the Czechs in Volyn is the correspondence of many toponyms of Volyn and the Czech Republic (see section Czech and Slovak Place Names in Ukraine). It follows from this that if the Teutonic traces have survived in the anthroponymy of the Ukrainians, then they should all the more be present among the Czechs. If they are not found, then the correspondence of the Ukrainian toponyms to the German language will need to be recognized as accidental and their interpretation should be different.

Searches for Teutonic anthroponymy among Czechs were carried out according to the alphabetical catalog of Czech surnames presented on the website Kde jsme. First of all, the presence of surnames similar to the Ukrainian ones, which were discussed above, was checked. However, it is not at all necessary that they all have Czech counterparts, and some Czech surnames may come from completely different Teutonic roots. As a result, it turned out that the following Czech surnames may have Teutonic origin:

Šimek, 6790 carriers, most of all in Prague (745), České Budějovice (214), Brno (177), Olomouc (147), Jihlava (143), Šumperk (128), Plzeň (125), Náchod (115), Hradec Králové (113), Ostrava (109); Šíma, 2809 carriers, most of all in Prague (326), Kladno (176), České Budějovice (174); Šimeček, 1445 carriers, most of all in Prague (146), Opava (82), Kyjov (81); Šimák , 856 carriers, most of all in Prague (125) and Tábor (90); Šimko 373 носителя, Šimka, 116 carriers, as well as many surnames Šimčak, Šimček, Šimeček, Šimčo, Šimer, Šimera, Šimiak, Šimić, Šimik and others with less than a hundred carriers – OHG. scīmo "ray, shine".

Šach, 343 carriers – OHG. scāh "robbery".

Šich, 254 carriers – OHG. schiuhen "to be afraid".

Burk, 147 carriers – OHG. burg "town, burg";

Šoch, 106 carriers see Šich;

Šůra, 63 carriers, Šurá – 40, Šura – 23 – OHG. skūr, "storm, downpour".

Lempera, 52 carriers, Lempach (10), Lempel (7) – OHG. limpfen "limp";

Stec, 63 Carriers, Stets (53), Stecko, Steckí – OHG. stecko "stake, club";

Price, 27 carriers, Pric (4) – OHG pricke 1. "engraver", 2 "harpoon".

However, in the Czech language, there are surnames of possible Teutonic origin with a fairly large number of carriers, which are not found in Ukraine and Germany or are found in isolated cases. For example, Šída, 231 carriers in the Czech Republic – OHG. scidōn "split"; Belda (106) – OHG beldan "get bold". There may be many such surnames, but they can refer to the time when the ancestors of the Czechs settled the country of the Teutons in Central Europe in the middle of the 6th century.

A Slavic tribe of Slovaks was formed in the ancestral home of the Anglo-Saxons. Accordingly, some Slovak surnames may have been of Anglo-Saxon origin, but the list of Slovak surnames available on the Internet is rather short. Nevertheless, in 1995, 1065 carriers of the surname Šimek (OE scīma "ray, light, shine") were recorded in the following areas: Kuty (Senica district) 79 carriers, Bratislava -56 , Trnava -44, Kuklov (Senica district) -31, Jakubov (Malacky district) 30, Senica -29.

However, there is historical evidence that we can talk about the presence of the Aglo-Saxons in their historical ancestral home even during the time of Kievan Rus. In 970, the Byzantine emperor John I Tzimisces (969 -976) conveyed a message to the Kiev prince Svyatoslav (964 – 972) through ambassadors, which contained the following words:

For I think you are well aware of the mistake of your father Igor who, making light of the sworn treaties, sailed against the imperial city with a large force and thousands of light boats but returned to the Cimmerian Bosporos with scarcely ten boats, himself the messenger of the disaster that had befallen him. I will pass over the wretched fate that befell him later, on his campaign against the Germans, when he was captured by them, tied to tree trunks, and torn into two (LEO the DEACON, 1988, VI: 10).

Here we are talking about Prince Igor, who died a martyr's death at the hands of the Drevlyans, who inhabited the area of the Anglo-Saxons, and the origin of the ethnonym "Drevlyans" can be deduced from the name of the well-known Germanic tribe Turvin (YAYLENKO V.P., 1990: 116). For a long time, the Drevlyan tribe was not part of the ancient Russian state. At least in the 10th cent. Drevlyans were not included in it, which was repeatedly emphasized in his work by A.N. Nasonov (NASONOV A.N.., 1951, 29, 41, 55-56). The fact that the Varangians, who stood at the origins of Kievan Rus, could not include the nearest land of the Drevlyans into this state, may indicate the existence of enmity between the Varangian newcomers and the tribal elite of the Slavs of Anglo-Saxon origin. It began after the murder of princes Askold and Dir in Kyiv by the Varangian leader Oleg in 882. (For more information about the Anglo-Saxon origin of Askold and Dir, see the section Anglo-Saxons in Eastern Europe ).

Summing up, we can say that since the publication of the first work about the ancestral home of the Germanic people in Eastern Europe (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998), more than enough evidence has been obtained to confirm this position.