Ancient Turkic Place Names in Eastern Europe

The Turkic people, who at the beginning of the 5th millennium BC. settled the area between the Dnieper and Don rivers, became the creators of the Corded Ware culture (CWC), which was widespread in Europe from the Volga to the Rhine and from Southern Scandinavia to the Carpathians (see sections "Ethnicity of the Neolithic and Eneolithic cultures of Eastern Europe. " and "Türks as Carriers of the Corded Ware Cultures "). The only descendant of those Turks who have survived to this day are the modern Chuvashes, and their language has preserved the features of the Proto-Turkic language more than other Turkic languages. Most of the Turks have assimilated among different peoples of Europe, but those who inhabited Western Ukraine retained their ethnicity and in the first millennium BC again settled in the vast expanse of Eastern and Central Europe. They became known in history as the Scythians and were the ancestors of the modern Chuvash, which is why the Chuvash language is used to interpret Turkic toponyms. They can be deciphered in other languages only in individual cases. The Turks who inhabited Western Ukraine will be called Proto-Chuvashes (see. the cycle "The Scytho-Sarmatian Problems").

The Turkic people left traces of their stay in many place names, which can be divided into two groups – the time of CWC and Scythian times. The place names in Scandinavia, Germany, and most parts of Poland belong to the first group. These include a strip of names, which stretches from Left-Bank Ukraine to the north in the area dissemination and Fatyanovo Balanovo cultures. It is also confident to say that the second group includes place names of Hungary, left-bank Ukraine, and two strips from Western Ukraine, one in the direction of the Dnieper River and the other to the Black Sea.

In general, if we consider each place name separately, then an element of random coincidence remains always in case of the absence of good correspondence to local conditions. Particularly isolated toponyms can be often doubtful, while we can confidently talk about the stay of the Turkic people where place names form clusters or chains marking the ways of their migrations. It should be noted that random coincidences have an unsystematic nature and therefore do not distort the picture of the placement of certain groups of toponyms when they are numerous, and even more when they can be associated with certain archaeological cultures.

Among the clusters of toponyms of Turkic origin are present those that directly indicate the Chuvash ethnicity of the inhabitants of some settlements:

Chaus, a village in Mezhev district of Dnepropetrovsk Region. Ukraine.

Chausove, a village in Pervomaysk district of Mykolayiv Region. Ukraine.

Chausove, a settlement in Zhukovskiy district of Kaluga Region. Russia.

Chausy, a village in Pogar district of Briansk Region. Russia.

Chausovo, a village in Novodugino district of Smolensk Region. Russia.

Chavusy, a town im Mogilev Region. Belarus.

All the given names contain a root that corresponds to Chuv. chăvash "Chuvash". The Proto-Chuvashes remained in the indicated settlements until the arrival of the Slavic population, who named them following the self-designation of the inhabitants. A table sort of grapes called "chaus/chaush" is known and the Russsian name Chausov is known, but the origin of these words has not yet been explained. There is a word of non-Romance origin ceauș "courier, messenger" in Romanian. It also comes from the self-name of the Chuvashes since Scythian times.

The most common Turkic place names in Eastern Europe are Mayak and Mayaki, which can be associated with Chuv. lighthouse "landmark" which comes from the Chuv. may "side", "direction", "method", "reason", or "case". In Russia alone, there are about fifty toponyms of Mayak, although some of them come from the name of a navigational landmark. However, in favor of the Turkic origin of others is the fact that one of the most common toponyms in Russia, numbering more than a hundred cases, is the name Markovo, which is associated with OE. mearc, mearca "boundary", "sign", "county", "marked space", i.e. in a meaning close to the Chuvash word. In this one can see a certain pattern in the naming of geographical objects by ancient peoples. It is almost impossible to separate the toponyms Mayak of Turkic and Russian origin; one can speak more confidently about those who are among the clusters of other Turkic ones. Those that are located in isolation should not be taken into consideration. In this case, in Russia, one can count at least twenty-five names of Turkic origin, and fifteen in Ukraine. There are fewer place names Mayaki, but it can be assumed that almost all of them are of Turkic origin.

At the second mill BC, the Proto-Chuvashes occupied the country on the left bank of the Dniester (STETSYUK V. 1999: 85-95; STETSYUK V. 2000: 28). The border between their habitat and the Teuton area lay across the watersheds of the Pripjat’ and Dniester. As this boundary was feebly marked, linguistic contacts of the Turkic people with Teutons and other Germanic tribes were rather close, as the numerous lexical matches between the modern German and Chuvash languages make clear. This fact has been noted by several researchers working independently of each other (KORNILOV G.E., 1973; YEGOROV GENNADIY., 1993; STETSYUK VALENTYN., 1998). The Proto-Chuvashes' stay on the mentioned territory is confirmed by local place names, which can not be explained using the Slavic languages but are understandable using Chuvash. The bulk of Turkic place names is concentrated in the Lviv region, but in large quantities, they are also found in the Volyn region, in the Carpathian Mountains, and adjacent localities of Hungary and Poland.

While deciphering place names the following phonetic correspondences between the Ukrainian and Chuvash languages were revealed:

The letters ă and ě reflect reduced sounds a and e. In Ukrainian pronunciation, the sound ă can correspond to the vowels o, a, and less often u

Chuvash letter u correspond historically most often to sound a, seldom to u.

Chuvash letter a can correspond to Ukrainian a and o.

Chuvash letters e and i correspond to Ukrainian e and i though mutual substitutions are possible.

Chuvash consonants differ little from Ukrainian ones, but Chuvash previous sound k has evolved into x (kh) and g into k, that is, words with g don't exist in the Chuvash language do not, except for loan-words. Other features are:

Chuvash letters reflecting voiceless consonants may sound more voiced at the beginning of words and before vowels (for example, p sounds closer to b).

The letter ç reflects a sound close to the Ukrainian z' or c'. Because the voiceless consonants often have a voiced pair, then ç may also correspond to Ukrainian dz. Chuvash sound reflected by the letter č can be derived from the ancient Turkic t.

The most common Turkic appellative for the names of settlements may be the ancient Türkic word jöke "linden", presented in similar forms in many modern Türkic languages. In Chuvash, they correspond to çăka. In Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland there are more than a hundred toponyms with the root zhuk "beetle", more than eighty names of Zhukovo alone were found, in addition, there are toponyms Zhukovka, Zhukovskaya, and others. However, it is highly doubtful that the Slavic name of the beetle insect was so often used for the names of human settlements. Deciphering the names of Zhukotin villages in Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk regions confirms the hypothesis made. The second part of these toponyms – tin is not a possessive suffix, but a wandering word with the meaning "village", "settlement", or "fence" (for more details, see the section "Ancient Anglo-Saxon Toponymy"). The existence of the ancient city of Zhukotin in Volga Bulgaria confirms the Turkic origin of the name. On the other hand, the predominant number of toponyms with the root "zhuk" is located among other toponyms of Turkic origin. Despite this, toponyms with the morpheme zhuk are not marked on the map, since it is impossible to separate the Turkic and Slavic names.

Another widespread toponym of Tukic origin from the name of a tree is containing the root almaz "diamond". They should be associated not with the name of the mineral, but with the Turkic. alma "apple", "apple tree". In modern Chuvash, it has the form ulma and together with the affix çă (pronounced approximately as zya), which serves to form nouns from nominal stems for designations of the person, tools and implements, products of activity indicated in the basis, may mean a gardener or seller of apples. There are at least five Almazovo villages in Russia, and there are Almaznaya and Almazny settlements in Ukraine. In addition, in some cities of Ukraine and Russia, Almaznaya streets have retained the names of former villages.

The most convincing place names in Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia decoding using the Chuvash language are submitted further.

|

UKRAINE

The most convincing examples of place names of Turkic origin are those that can be associated with the geographical terrain features. For example, the town of Khyriv in the Stary Sambir district of Lviv Region is located in an area rich in pine forests. Since the Chuvash xyr means "pine tree ", the origin of the name from this word is probable. When similar examples could be found enough, the presence of the Proto-Chuvashes in Western Ukraine should not be doubted. Sometimes the connection of a name with the peculiarities of settlements is compelling. The village Havarechchyna not far from the town of Zolochiv in the Lviv Region is known for black pottery, which is manufactured according to the old original technology of firing clay

The name of the village namely points out to the folk craft spread here – Chuv kăvar "embers" and ěççyni "a worker" united in kǎvarěççyni would mean "a worker with hot coals", that is "a potter".

At left: Black pottery from Havarechchyna . Photo: PARK-PODILLYA.COM.UA

A common surname Bakusevich in this village can also have Turkic origin since an old man's name Pakkuç was used by Chuvash. The name of the village Kobylechchina, located in the south-east of Zolochev also contains the same word as in Havarechchina. For the first part may be suitable Chuv. hăpala "to burn" which in meaning and even phonetically stands close to the Chuv. kăvar. Then, pottery existed in this village too.

The name of the rocky ridge Tovtry in western Ukraine could be etymologized by Chuvash tu "mountain" and tără "top". As the name of the mountain sounds tau in many other Turkic languages, the primary name of the ridge could be Tautără. The mountain range on the border of Slovakia and Poland Tatry had the same protoform too. Tovtry stretches from Zolochiv in the Lviv Region to northern Moldavia and appears as separate limestone ledges and ridges that protrude above the surrounding expressive, mostly fairly level terrain, ie explanation as "mountain peaks" fits very well (see the photo of Iryna Pustynnikova above).

On the contrary, the name for the village Voronyaki and special for the part of the ledge Holohory on the western outskirts of Podol Upland can be decoded as "smooth, flat place" following Chuv vyrăn "place" and yak "smooth" (see the photo left). Such an explanation of the name suited for this locality and is semantically close to the name Holohory (Ukr. "naked mountains").

L. Krushelnic’ka distinguishes the Cherepin-Lahodiv group in archaeological relics of the Hallstatt period in the north-eastern Carpathian region which corresponds to Early-Scythian time. Many relics of this group are concentrated in a strip of land extending from the village of Cherepin in the Peremishljany district of L’viv Region, through Zvenyhorod and Lahodiv eastward along Holohory to the village of Makropil’ in Brody district. Many place names on this territory can be decoded using the Chuvash language. Besides mentioned above Voronyaky we can find the village Yaktoriv here, which name is decoded as “level-mountain” (Chuv. yak "smooth". and tǎrǎ “top"). There's a mountain called Kamula southeast of the village of Zvenyhorod, which having 471 meters above sea level, is the highest point of Ukraine outside of the mountains of Carpathian and Crimea. Chuv. kamǎr čul “stone clump" (čul "stone") is a good match for the name of this mountain. Kamăr is also well suited because different languages have similar words with similar meanings (Lat cumulus, Lith. gumulus "heap", Alb. gamule "pile of earth," Bash. kömrö "hump").

There is a high stone rock with the mysterious name Tustan' not far from the city of Drohobych. Attempts to etymologize this name have not yet yielded satisfactory results. It can be explained with the help of the Chuvash language as a “stone hill”, which is fully consistent with reality, taking into account Old Chuv. *tus "stone" and těm “hill, hillock”. Chuv. chul "stone" goes back to the common Turkic protoform tāsh (SEVORTYAN E.V.. 1980: 167-168). The supposed intermediate form in the formation of the Chuvash word should have been exactly tus.

The name of the swift Poltva River flowing through the city of Lviv also has Proto-Chuvash origin (Chuv. paltla, “swift").

Since the toponyms that we have found in this small part of the Cherepin-Lahodiv group of monuments presumably originate from Scythian-Proto-Chuvash names inspired by nearby natural formations, we have a basis for trying to etymologize other toponyms with unclear origins in the area via Chuvash. A cluster of settlements with original names is located several kilometers south of Lahodiv. Some of them may be decrypted by way of Chuvash: Korosno – Chuv. karas, “poor;” Peremyshlany – Chuv. pěrěm, “skein, hank;” eşěl, “green;” Kimyr – Chuv. kěměr, “heap, great lot;” Chupernosiv – Chuv. çăpar, “motley,” masa, “appearance;” Ushkovychi – Chuv. vyşkal, “similar.” A few more examples of Scythian-Proto-Chuvash place names in the Lviv Region follow:

Chyshky, a village to the south-east of Lviv, the village of Chyzhky on the north of Staro-Sambir district – Chuv/ chyshkă “a fist”;

Kutkir, a village in Busk district – Chuv kut “a trunk”, khyr “pine-tree”.

Tetyl’kivci, a village near the town of Brody – Chuv. tetel “fishing network”;

Turady, a village west of the town of Žydačiv – Chuv. turat “branch, brushwood”;

Tsytula, a village west of the Town of Zhovkva – the name can have two explanations I. Chuv. çi 1. “to eat”, 2. "to rub", tulă, “wheat”; II. Chuv çută "light", "fire", "bright", "beauty"; -ula – Ukrainian tender suffix to previous name Tsyta;

Veryn, a village south of Mykolajiv, and the village of Veryny near the town of Zhovkva – Chuv. věrene “maple”.

Further to the east of the Lviv Region, the amount of the place names of Turkic origin decreased gradually, but surprisingly, they form a clear chain of settlements at a distance of 10-20 km from each other (Sokal, Tetevchitsi, Radekhiv, Uvin, Corsiv, Tesluhiv, Basharivka, Tetylkivtsi near Pidkamin’, Kokorev, Tetylkivtsi near Kremenets, Tsetsenivka, Shumbar, Potutoriv, Keletentsi, Zhemelintsi, Sohuzhentsi, Savertsi, Sasanivka, Pedynka, Sulkivka, Ulaniv, Chepeli, Shepiyivka, Kordelivka, etc.) This chain extends from Sokal in the north of Lviv region above Radekhiv to Radivyliv, then turns east and runs south of Kremenets, Shumsk and Iziaslav to Lubar, then turns south-east, goes above Chmilnyk through Kalynivka, and there's not a chain already but a whole band of names going in the direction to the Dnieper River, they can be found in large numbers on both sides along.

West of Cherkasy, a bog separates the Irdyn’ and Irdyn’ka, rivers that flow into the Dnieper below and above the city respectively. Looking at a map, one may observe that these two rivers were once part of a channel that separated from the Dnieper, leaving behind the island on which the city of Cherkasy was built. The Chuvash verb irtěn, “to be separated," expresses that situation rather well. The name of the city can have Proto-Chuvash origin too as well as more than ten similar names in the whole of Eastern Europe. There are villages Cherkasy in Pustomyty district of Lviv Region, in Kovel district of Volyn Region, Czerkasy in the neighboring Lublin Voivodeship of Poland (Tomaszew County, Lashuv commune), and there are four villages of Charkasy in Belarus. In Russia there are even more settlements in the form of Cherkassy; some of them are located on the Chuvash ethnic lands, but they are present also in the Kursk, Lipetsk, Tula, and Tver Regions. In Chuvashia itself there are at least a dozen settlements with an end -kassy: Anchikassy, Oykassy, Kachakassy, Irkhkassy, Torkassy, Khirkassy, Chulkassy, Sharkassy, etc (EGOROV GENNADIY. 1993, 38). Such names are a typical attributive construction in Turkic languages when the defined name takes the possessive affix of the 3rd person singular (that is, in this case sy). Chuv kasă “village, street, new settlement” in such construction have to take the form kasăsy, which is reduced to kassy. Chuv. kĕr "autumn" is well suited as the definition for toponyms of this type, that is the settlement had a meaning of "autumn village". The accepted interpretation becomes more convincing if one takes into account the similarity of this meaning to the sense of the widespread Turkic kyshlaq, which is translated as "winter residence" (from qysh "winter" of the same origin as Chuv. kĕr). Turks pastured livestock in a nomadic way in the summer but in autumn stayed in one place where hay was stored in advance for the winter. Such sites were called cherkassy or kyshlaq. The name of the Lithuanian village of Kerkasiai of the same origin preserved the original sound k, while it moved to ch in the Slavic languages (known interchange of consonants).

Names of the village of Kandaurovo and the river Kandaurovs’ki Vody, lt of the Inhul derive from Chuv. kăn “potash” and tăvar, "salt". It has been assumed that the Proto-Chuches could obtain salt in this area from evaporation, selling it to their neighbors (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 57). But here we are not talking about common, table salt, because then there would be no need for a special attributive for the word tăvar. Therefore, potash (potassium carbonate) may be implied. The deposits of this salt are found in nature and it is known to people from ancient times. Potash tastes bitter, and just Herodotus mentioned the river with bitter water in Scythia. Describing the Hipanis River (Ὕπανις), he noted that the water is fresh in this river, and within four days of its journey from the sea the water becomes very bitter. Hypanis is usually associated with the Southern Bug, but it is possible that the sources of the Inhul were taken for its sources, the water of which became bitter just after the confluence of the Kandaurov’ki waters.

The third river is the Hypanis, which starts from Scythia and flows from a great lake round which feed white wild horses; and this lake is rightly called "Mother of Hypanis." From this then the river Hypanis takes its rise and for a distance of five days' sail it flows shallow and with sweet water still; but from this point on towards the sea for four days' sail it is very bitter, for there flows into it the water of a bitter spring, which is so exceedingly bitter that, small as it is, it changes the water of the Hypanis by mingling with it, though that is a river to which few are equal in greatness. This spring is on the border between the lands of the agricultural Scythians and of the Alazonians, and the name of the spring and of the place from which it flows is in Scythian Exampaios, and in the Hellenic tongue Hierai Hodoi "The Sacred Ways" (Herodotus, IV, 52, translated by G.C. Macaulay).

Herodotus’s Hypanis commonly corresponded to the Southern Buğ river. Since the Kandaurovs’ki Vody flowed into the Inhul, the Ancient Greek historian probably had another bitter river in mind. This may not be so important, however: deposits of potassium chloride (a source of potash) can be found in this locality, and so bitter water may flow through many of its rivers. In particular, B. Ribakov attributes a bitter taste to the water of the Black Tashlik, which flows into the Siniukha (RYBAKOV B.A. 1979: 36). More important for our purposes is the Turkic origin of the river name Kandaurovs’ki Vody, a real oddity for this locality.

Especially noteworthy is a band of names that goes running along the flow of the Vorskla River and then goes to the Psel River. This corresponds well to the spread of Chornolis culture. Let us review the place names from the mouth of the Vorskla and farther up its course.

Bulakhy, a village between the Vorskla and Psei Rivers – Chuv. pulăx "fertility";

Abazivka, two villages, the one next to Poltava and another in Kharkiv region in the southeast of the town of Krasnograd – Chuv. apăs "a priest", "a midwife", and Chuvash pagan names Apuç and Upaç is well suited/ However the name can have Greek origin (Gr. ἄππας "a priest").

Bishkin', a village on the Psel River near the town of Lebedin in Sumy Region – Chuv. pĕshkĕn "to incline, lean".

Gozhuly, a village next to the city of Poltava – Chuv. kăshăl "a ring".

Kalantayiv, a village in Svetlovodsk district of Kirovohrad Region, Kalantayivka, a village in Rozdilna district of Odesa Region, Kolontayev, a village in Krasnokut district of Kharkiv Region – Chuv. kălantay "slacker, lazy” (private message), kălin "slacker, lazy", -tay is an affix that forms adjectives from nominal stems with the meaning "possessing in excess the feature indicated in the stem" with a hint of contempt.

Kuyanivka, a village in the south suburb of the town of Belopilla in Sumy Region – Chuv. kuyan “a hare”.

Sahnovschina villages on the riverside of the Tagamlyk River, lt of the Vorskla River and in Kharkiv Region in the south-east of the town of Krasnograd – Chuv. săkhăn "to flow", "to soak", "to saturate".

Khukhra, a village at the mouth of the river of the same name falling into the Vorskla River– Chuv. khukhăr "empty", "not full".

However, there are on other territories of Ukraine many Turkic place names which can be often acknowledged by logical-semantic connection of parts of words and by the cases of almost complete phonetic identity. Compare:

Gelmiaziv, a village near the town of near Zolotonosha – Chuv. kělměç “a beggar”.

Katsmaziv, a village southwest of the town of Sharhorod in Vinnycja Region – Chuv. kuç “eye”, masa “appearance”.

Khalayidove, a village southwest of the town of Monastyryshche in Cherkasy Region – Chuv. xăla, “red” jyt, “a dog”.

Kretivci (from Kretel), a village southeast of the town of Zbarazh in Ternopil Region – Chuv. kěret “open”, těl “place” (the village is located on a level, open place).

Kudashevo, a village south of the town of Chyhyryn in Cherkasy Region – Chuv. kut, “buttocks,” aş “meat”.

Odaiv, a village in Tlumach district in Ivano-Frankivs'k Region, the village of Odai in Kryzhoplil district of Vinnytsa Region, and the hamlet of Odaya near the village Chun'kiv in Zastavna district of Chernivtsi Region – Chuv. ută 1. “hay”, 2. “island, valley”; ay “foot of, low, lower”, uy “field”; yal, yav “a village, settlement”; yăva 1. “home”, 2. “nest”; ya, yav “to twine”. At left: the village of Odaiv.

Ozdiv (from Oztel), a village southwest of the city of Luc’k – Chuv. uçă “open”, těl, “place” (the village is located on a level place).

Potutory, a village in Berezhany district and the village of Potutoriv, east of the town of Kremenec’ in Ternopil’ Region – Chuv. păv, “to press, squeeze,” tutăr, “shawl”.

Shuparka, a village in Borshchiv district in Ternopil’ Region – Chuv. çăpărka “a whip”.

Temyrivci, a village west of the city of Halych – Chuv. timěr, “iron”.

Tseptsevychi, a village west of the town of Sarny in Rivno Region – Chuv. çip, “thread”, çěvě “seam”;

Tymar, a village south of the town of Haysin in Vinnytsia Region – Chuv. tymar, “a root”;

Uman’, a city in Cherkassy Region – Chuv. yuman “oak”. It is characteristic that there was in Uman natural oak grove from which remained only one 300-year-old oak tree (see the photo at right).

Urman’, a village in Berezhany district, Ternopil’ Region – Chuv. vărman “forest" (the village is surrounded by forests);

Zhurzynci, a village north of the town of Zvenyhorodka in Cherkasy Region, and the village Zhurzhevychi, north of the town of Olevs’k in Zhytomyr Region – Chuv. şarşa “smell”.

Carpathians

When searching for traces of the Turkic people in the toponymy of lowland areas of western Ukraine, where their stay of has other evidence, it was pointed out that some of the place names in the Carpathians may also have Turkic origin (STETSYUK VALENTYN, 2002: 16-17).

Names of mountain summits

The highest mountain in Ukraine is named Hoverla (2061m above sea level). The decoding of the name using the Slavic and Romanian languages gives no acceptable results. Given Chuv kǎvar “hot coal, embers” with the suffix -la which is used for the formation of adjectives, the name of the mountain could be explained as “puffing with heat”. Such a name would suit well a mountain of eruptive origin, but geographers deny such formation of Hoverla. (Volcanic Carpathians are located at the border of the Transcarpathian lowland). However, the very heated stone scattering of Hoverla in summer could be the reason for the name of the mountain.

Mt Breskul or Bretskul (1911 м). There is a lake on the South-West slope of the mountain. Chuv păras"icy" and kўlě "a lake" are present in the name. Cf. Turkul.

Mt Dancyr (1848 м). Taking into consideration Chuv tun “to break off” and çyr ”steep, gully”, one can assume that a part of the mountain broke away once, forming a precipice. Both the reason for the mountain name and the phonetic correspondence are good. It is necessary to mean, that Chuv u corresponds often. Ukr a.

Mt. Dzembronia (1877 м) see the Dzembronya River.

Mountain range Kakaraza (highest point 1558 м). Chuv. kukār "crooked, sinuous" and aça "belt" agree with range form.

Part of landscape Kalatura – “yellow mountain” (Chuv khălă “yellow” and tără “a mountain, top”). Though Romanian tură "a rock" can be taken into consideration for this and two next names too.

Mt. Karatura near the village of Nyzhni Bereziv – “black mountain” (Chuv khura “dark” and tără “a mountain, top”).

Mountain range Karmatura – given the latter names Chuv tără "mountain, top" is present here too. Chuv karmash "to stretch" can be suggested for the first part of the name.

Mt. Kukul (1539 м). Chuv kukǎl “pie, tart” befits phonetically perfectly to the name. The naming reason for it is not quite clear, as it unknown is what form of pies was baked by ancient Proto-Chuvashes. However, the Baltic-Finnish languages have similar words with the meaning "hill, summit, height" (Fin. kukkula, Est. kukal a.o.). They were also borrowed from the Proto-Chuvashes, who were the creators of the Fatyanovo culture in the upper reaches of the Volga River when the ancestors of the Baltic Finns still dwelled there.

There are a few mountains and peaks with similar names Manchul, Menchul, Menchil in the Carpathians. Undoubtedly they have to be decoded as "a great stone" (Chuv. măn "great", chul "stone"). There are in the Carpathians tops which have in their Ukrainian names the word "stone" – Great Stone, Sharp Stone, Painted Stone, etc.

Mt. Mingol (1085 м). Chuv. phonetic correspondences min “roses, ruddiness” and kul “to laugh” are unacceptable for the name of the mountain. Most likely, this is a modification of the name Manchul (see).

The tops of mountains having name Magura are present in the Carpathians in great numbers. As the word became also denominative meaning, their quantity cannot be counted. Certainly, it can be accepted to consider the Slavic word gora “a mountain”, but the prefix ma- remains incomprehensible as also phonetic transformation. Cuv mǎkǎr “hill, bump” suits the name of the mountain. The ending –а was accepted under the influence of Slavic gora.

Mt. Parashka (1268 m). It is unlikely that the mountain's name comes from a female name. Chuv. purăsh "badger" with performative adjective suffix -kă suits well. That is "Badger Mountain".

Mt. Sikitura near the village of Sheshory – Chuv sikĕ "descent, fall", tără "a mountain, top".

The name of a small mountain Tempa (1089 meters) has for the first part in the Chuvash language good correspondence: tĕm "hill, mound". The second part can be something like Chuv. pÿ "body, figure, growth."

A certain lake is situated at the foot of the mountain Turkul which gives grounds to consider for the explanation of the name Chuv tără "mountain, top" and kўlě "a lake".

Mountain Pass Shurdyn. Chuv shărt which among others has the meaning “ridge (crest) of the mountain” and en “side, land” suit well for the name.

Rivers

The names of Carpathian rivers could also be decoded using Chuvash but phonetic correspondences wish to be better sometimes. However, in principle, the names of rivers must be more submitted to modifications than the names of mountains, because they are more frequently used as settlements are located mainly on river banks, not nearby mountains.

The Dzembronya, lt of the Black Cheremosh, and the village of the same name – чув. çĕnĕ "new", părănu "turn".

The Tisza. This name can stem from the plant yew (Ukrainian tys) which was widespread in the Carpathians in great numbers many years ago, but we could take into consideration Chuv tase “clean” which good suits to river name. If the contamination of two meanings took place, the explanation of the name can be very plausible.

The names of some Carpathians rivers have endings -shava, -shva, -zhava. Chuv šăv “water, river” suits the names as an appellative very well. The ending –а could have corresponded to the special Turkic grammar form (the ezafe – šăva). Thus, the name of the Borzhava River is transformed out of Chuv pǎr šăva “ice river” (pǎr out of OTrc buz “ice”).

The name of the Irshava, rt of the Borzhava, rt of the Tisza, lt of the Danube – “morning water” (Chuv ir “morning”).

The Latorica, lt of the Bodrog, rt to the Tisza – Chuv lutra "low", although it can originate from Rom. lotru "fast".

The Kevele, lt of the Tisza – Chuv. xĕvel "sun", xĕvellĕ "sunny".

The Salatruk, lt of the Bistritsa-Nadvirnyanska, rt of the Dniester. The name looks Turkic. The first part may have Chuv salat "to scatter, sprinkle," but decoding the second part is difficult.

The Tevshak River, lt of the Apshitsa, rt of the Tisza. The name should be decoded as "winding" (Chuv tĕv "loop", -shak – adjective suffix).

The Teresva, rt of the Tisza – Chuv. tǎrǎ “clean”, shyvĕ “water, river”.

Names of settlements

Akreshory, a village in the Yabluniv settlement community of Kosiv district, Ivano-Frankivsk Region. One can see Romanian acru “sour” in the first part of the name Romanian, but nothing better as Rom şură for the second part was not found. The conjunction of these words is doubtful, therefore we can consider Chuv ukăr “tanning matter” which, has the same origin as Romanian acru and Chuv shury "swamp". Thus the name can be explained as "a tanning swamp". There are swamps near Akreshory.

Bolekhiv, a town in Ivano-Frankivsk Region – Chuv. pulǎx ”fertility”.

Dashava, a rural settlement in Stryi district, Lviv Region – Chuv tu “mountain”, shyvĕ “river”).

Two villages have the same name Zhukotyn (in the Lviv and Ivano-Francovsk Regions). The name can have a Slavic origin, although in this case the suffix of –otyn looks strange. But the matter is that one of the historical Chuvashian cities had exactly such a name. Then we have a reason to consider Chuv çăka “a linden” as an appellative for the name of settlements having linden trees. There are many linden trees in Zhukotyn of Lviv district.

Kalush, a city in the Ivano-Frankivsk – the name has a good correspondence in Chuv хulaš „a hillfort, city” out of xula "a town". Many of the Turkic languages have qala/kala "fortress, a city", which is considered to be Arabic borrowing qalha "fortress, citadel". However, all these words can be based on an ancient Nostratic root kal-/kel-, which had sensed "to hide, protect", received in different languages meaning "dwelling, building, fortress, town" (Hebrew kele "prison", Lat. cella "camera, cell," O-Ind. çālā "a house", Eng hall, etc.). See also Kolomyia, Kolochava.

Keveliv, a street in the rural settlement of Yasinia in Rakhiv district, Zakarpattia Region – Chuv xĕvel "sun", xĕvellĕ "sunny".

Kelechyn, a community in Khust district of Zakarpattia Region – two Chuvash words are well suited to each other – kĕlĕ "prayer" and chun "soul" and together could be the name of the village, but there is reason to doubt it because there is in the Transcarpathia a village having a similar name Perechyn which is difficult to decode using Chuvash, so Slavic word chin may be present in both names. Although the word kele is not like Slavic. Complicated case.

Kolomyia, a city in the Ivano-Frankivsk Region, Kolochava, a village in Khust district of Zakarpattia Region – the names of these settlements can stem from Ukr kolo “round” but the question is not clear -chava. In this connection, Chuv xula "city" and myiǎ can be considered for the name of Kolomyia. Chuv shyvĕ "river" would suit the second part of the name Kolochava.

Kosmach, a village in Kosiv district of Ivano-Frankivsk REgion – the Ukrainian kosmač means “a shaggy man” but we can consider as appellative also Chuv kasmač “a mattock, hook”.

Lumshory, a village in the rural community Turi Remety of Uzhhorod district, Zakarpattia Region – taking into consideration Chuv lǎm “moisture, humidity” and shur “a swamp” the explanation of the name could be “a moist swamp”.

Sykhiv, some settlements in the Carpathians and Fore-Carpathians – the name is strange for Ukrainians. Ukrainian ending -iv could be added to Chuv root sykh “watchful”.

Sheparivtsi, a village near the city of Kolomyiya – Chuv shǎpǎr “a besom”.

Sheshory, a village near the of Kosiv i Ivano-Frabjivs Region – the name could be decoded as “a wet swamp” {Chuv shü “to be watered” and shur “a swamp”). Something like to Lumshory (see).

Tseniava, two villages in Ivano-Francovsk Region – Chuv çěně “new”.

Turka, a city on Lviv Region – it is believed that the name origins from the word tur "a bull". Indeed, there are in the Carpathian Mountains the names of settlements, having in its composition the adjective turiy , but in this case, remains unknown suffix – k -. Moreover, there is in Poland near Lublin the village of Turka (see) which was noted in annals already in 1409. Such a coincidence compels us to look for another explanation. Turka has long been a trading center on the way from Hungary to Galicia, so we can consider the origin of the name from Proto-Chuvash. *turku "site, market place" (Chuv. turkhi "bidding").

Voronenka, a village in the rural community of Nadvirna district, Ivano-Frankivsk Region located among mountains on unusual for mountains and enough large space – the name could have Slavic origin, but we could consider Chuv vyrǎn “place, space” and yak “level, smooth, even”. Obviously, at first, the village was named Voroniaka or Voroniaky and later adopted the Slavic suffix – enka.

Vorokhta, a rural settlement located in Nadvirna district, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast located in a mountain canyon – Chuv varak “ravine” and tu “mountain” suit perfectly.

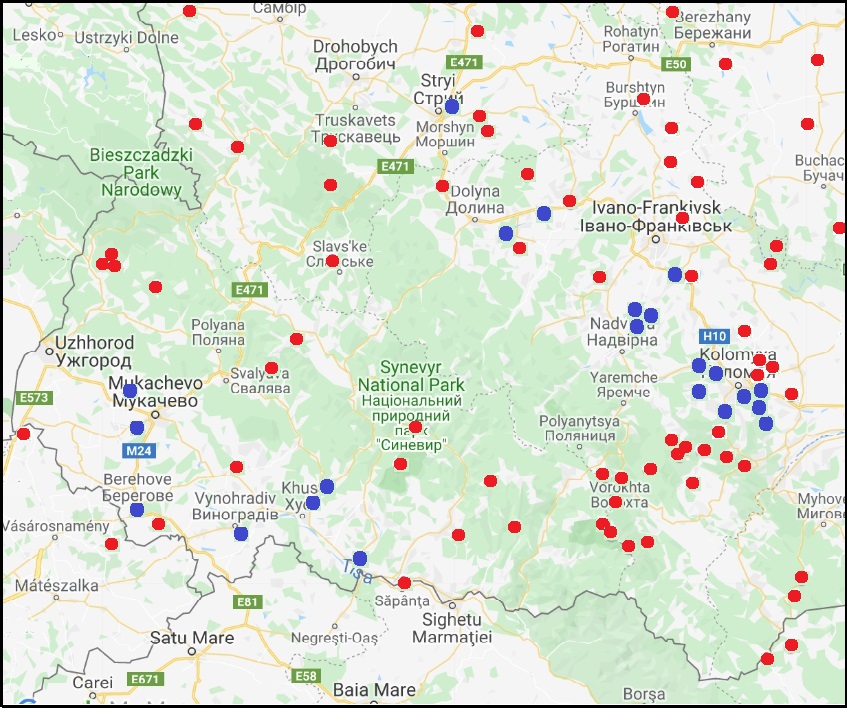

The largest cluster of Proto-Chuvash place names survived in a remote part of the Carpathians in the locality of Chornahora, while in the low Beskid land, practically the only Proto-Chuvash place name is the name of the village of Zhukotin in Turka district, Lviv Region. This is due there are low passes, which across lay the migration routes of nomadic peoples – Huns, Avars, and Magyars. Naturally, the autochthonous population here was not retained and the area was eventually empty:

The city of Turka, along with the rest of the outskirts from Old Sambora to Beskid was totally uninhabited forest wilderness to the half of the 14th century (PULNAROWICZ WŁADYSŁAW. 1929, 1).

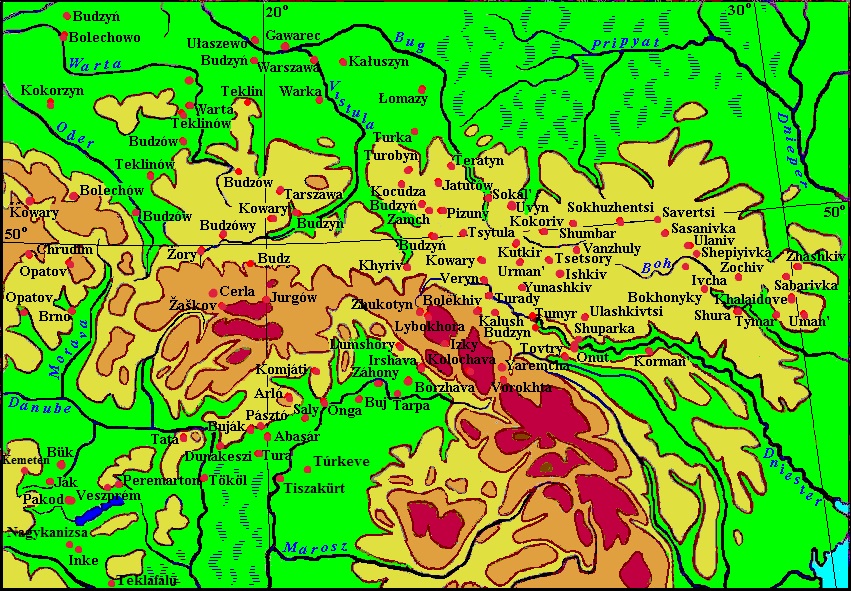

Multitudes of Turkic place names in Western Ukraine,

Poland, and Hungary.

This and similar map scales don't show all place names in their greatest concentrations. Furthermore, Turkic place names are found in large quantities in the Czech Republic, Germany, Baltic States, Finland, and Sweden. While continuing the search, displaying their extension on conventional maps becomes impossible. In such circumstances, there is no choice but to apply the new data to the map in the system of Google My Maps (see further).

|

POLAND

Bolechowo, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Czerwonak, within Poznań County, Greater Poland Voivodeship, Bolechów, a village in the administrative district of Gmina Oława, within Oława County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship – Chuv. pulǎch ”fertility”.

Bosutów, a village in Gmina Zielonki, within Kraków County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship – Chuv. păs "steam", ută "island", "grove".

Budzów, four villages in Lower Silesian, Łódź, Lesser Poland, and Opole Voivodeships- Chuv. puç buź "head", "spike", "chief".

Budzyń, about thirty place names of different types in Łódź, Lublin, Lesser Poland, Świętokrzyskie, Subcarpathian, Greater Poland Voivodeships – Chuv. puçăn "start".

Cerla, several places in the Silesian Voivodeship, Cerle, a village in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, Kielce County – Chuv. çĕrlĕ "having land".

Chabówka, a village near the town of Rabka, in the Nowy Targ County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship – Chuv. khapăl "hospitably".

Czuszów, a village a in t Gmina Pałecznica, within Proszowice County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship – Chuv. chukhă "poor, scanty".

Jatutów, a village in the Lublin Voivodeship, Zamość County – Chuv. yat "name", "reputation", "honor"ut "horse".

Jurgów, a village in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, in the Tatra County, Jurgi, a village in the Masovian Voivodeship, Ostrołęka County – Chuv. çărcha (Turkic jorğa/jurğa) "pacer" (Cf. Ger. Zorge).

Kaczawa (od Katszawa), a river in southwestern Poland, in Lower Silesia, lt of the Oder. – Chuv. khǎt "coziness", "usefulness", shyvĕ "river".

Kocudza Pierwsza, Kocudza Druga, Kocudza Trzecia, Kocudza Górna, villages in the Lublin Voivodeship, in the Janów County – Chuv. kaçă "pedestrian bridge, bridge" çu "wash".

Kokorzyn, a village in the Wielkopolska Voivodeship, Kościan County – Chuv. 1. kăkăr "breast", 2. kăkar "join".

Kowary, a city in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in the Jelenia Góra County – Chuv. kǎvar “embers, hot coals”.

Kujan, a village in the Wielkopolska Voivodeship, in the Złotów County, in the Zakrzewo gmina – Chuv. kujan "hare"

Leńcze, a village in Gmina Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, within Wadowice County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship – Chuv. lĕnche "weak, free".

Łomazy, a village in the Lublin Voivodeship, in the Biała Podlaska County – Chuv. lăm uççi "open damp place".

Łomża, a city in the Podlaskie Voivodeship – Chuv. lăm "moisture", shav "complete, total, everywhere".

Opatkowice, four villages in Lesser Poland, Lublin, Masovian, and Świętokrzyskie Voivodeships – Chuv. apat "food, nourishment, feed.

Paszkówka, a village in Gmina Brzeźnica, within Wadowice County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship – Chuv. păshka "pestle, mortar".

Poronin, wieś w woj. małopolskim, w pow. tatrzańskim, – Chuv. părăn "obrócić się, uginać".

Tarszawa, part of the town of Lasków in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, Jędrzejów County – Chuv. tără "clean" and szyvĕ "river".

Tenczyn, a village in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship, in the Myślenice County – Chuv. tĕncze "world".

Teresin, a rural gmina in Sochaczew County, Masovian Voivodeship – Chuv. tĕrĕs "right, proper".

Warszawa – Chuv. văra "mouth", szyvĕ "river".

Werynia, a village in the Podkarpackie Voivodeship, in the Kolbuszowa district – Chuv. věrene "maple".

Zamch, a village in the Lublin Voivodeship, in the Biłgoraj County – Chuv. çămkha "ball, tangle, skein".

Zaszków, a village in the Masovian Voivodeship, Ostrów County – Chuv. szaszkā "mink"

|

RUSSIA

Initially, Turkic place names in Russia were searched for only in the territories adjacent to Ukraine. When a sufficiently large number of them were discovered, it became clear that they could be linked to the advancement of the Turks, who were the creators of the Fatyanovo variant of CWC. Further searches were conducted in the area of its distribution. Since the Chuvash language was used in the searches, the more eastern toponyms can be attributed to later times, when the ancestors of the Chuvashes advanced to the Volga region and could then settle in the adjacent area. As a result of the search, it turned out that the toponyms of Turkic origin stretched in a strip between the Indo-European and Finno-Ugric territories. As it turned out later, the strip extends to a whole cluster of Turkic place names in the Bryansk, Moscow, Tver, and Yaroslavl regions.

In Russia there are more place names of Bulagarish origin than in Ukraine, but some of them are repeated many times. It is in the mentioned areas several tens of villages were discovered, bearing the name Akulovo or Okulovo. In general, there are more than sixty settlements of this type mainly in the northern regions northwest of the Tula-Nizhny Novgorod line. Chuv. aka "arable land, plowing" suits well for decoding the name. Decorated with an affix – la, the root forms an adjective with an equivalent meaning. There is also a verb akala "to plow" in Chuvash. Such a name is suitable very well for new settlements given by agricultural populations from the forest-steppe zone searching for vacant land. Also, some other place names of Russia testify to the agricultural character of the economy of the Turkic people who migrated to the Russian outback. Among them, numerous names of the villages Sharapovo which corresponds to Chuv. sărap "stack".

In total, over two hundred place names of supposed Turkic origin were discovered in Russia. The most convincing examples are given below:

Akatovo, fifteen villages in several regions– Chuv. akatuy is a mass celebration to mark the end of spring sowing.

Amon', a village north of the town of Rilsk, Kursk Region – Chuv. ăman "worm".

Amon'ka, a river, rt of the Pod', rt of the Seym, lt of the Desna River – as Amon'.

Apazha, a village in Komarichi district of Briansk Region – cf. Apash, a village in Cheboksary district of Chuvashia, Abashevo, and villages in other places of Volga regions. Perhaps from the pagan Chuvash name Apash of unknown origin.

Artakovo, railway station, the village of Artakovo in Odoyev district of Tula Region, the village of Artakovo-Vandarets in Konyshyovsky district of Kursk Region – Chuv. artak "friendly, warm, happy".

Babayevo, seventeen villages in several regions – Chuv. Papay Sxythian god.

Boldyrevo, four villages in Vesiegonsk, Vyshnevolotsk, Kesovogorsk and Staritsa districts of Tver Region and a village in Yaroslavl district of Yaroslavl Region – Chuv. păltăr "entrance-hall, closet".

Bolkhov, a town and the administrative center of Bolkhovsky district in Oryol Region – Chuv. pulǎkh "fertility".

Bolshevo, an area of the city of Korolyov in Moscow Region, villages in Novoduginsky district Of Smolensk Region and Pereslavsky district of Yaroslavl Region – Chuv. pălkhav "mutiny, revolt".

Khirovo, villages in Lyubytinsky and Moshenskoy district of Novgorod Region – Chuv. khyr "pine tree".

Kokorevka, a town in Suzemka disrtict of Briansk Region – Chuv. kakăr "hooked pole".

Kokshenga, a river, lt of the Ustya, rt of the Vaga, lt of the Northern Dvina, a railway station in the Velsky district of the Arkhangelsk Region – Chuv. kaksha "to dry up", enkkě "willow".

Kolontaevka, a town in Lgov district of Kursk Region, Kolontaevo, a town in Bolkhov district of Orel Region, the villages of Kolontaevo in Suvorov district of Tula Region and Noginsk district of Moscow Region – see Kalantayiv

Konyshyovka, a town in Kursk Region, villages Konyshevo in Kolchugin district of Vladimir Region, in Antropov district of Kosntoma Region, in Pskov district of Pskov Region – Chuv. kănăsh "rubbish, garbage, trash".

Kostroma, region center – Chuv. kăstărma "whirligig, peg-top".

Kozelsk, a town and the administrative center of Kozelsky district in Kaluga Region – Chuv. kĕçĕllĕ "psoric".

Kurakino, seventeen villages in several regions – Chuv. kurăk "green", "grass".

Kutuzovo, eight villages in several regions – Chuv. khutaç “sack, bag”.

Nerl, rivers – rt of the Volga and lt of the Kliazma, a town in Ivanovo Region, a village in Kalazin district of Tver Region – Chuv. nĕrlĕ "nice".

Odoyev, a town of Tula Region – see Odaiv

Orsha, towns in Vitebsk and Kalinin Regions, villages in Novorzhev district of Pskov Region and Kalinin district of Kalinin Region – чув ăsha "darkness, mirage".

Perkino, villages in Spassky and Ryazansky districts of Ryazan Region and Sosnovsky district of Tambov Region – Chuv pĕrke "envelop, wrap up".

Shablykino, a town in Oryol Region, villages in Aleksandrov district of Vladimir Region, Krasnoselsky district of Kostroma Region, Istra and Pushkino districts of Moscow Region, Krasnokholmsky district of Tver Region – Chuv. shăplăkh "stillness, lull". There are in Poland two villages of this root. Lull is a good name for a village.

Sharapovo, about thirty villages in several regions – Chuv. shar "very, at all", apav is a word expressing surprise, joy.

Shatovo, a village in Serpukhov district of Moscow Region – Chuv. shat "tight, close, next".

Serpukhov, the city of Moscow Region – Chuv. sĕr "to rub" pakhav "a plane, knife plane".

Tarusa, a town in Tarussky district of Kaluga Region – Chuv. tărăs "birch bark basket".

Tarutino, four villages in several regions – Chuv. tără "tot, roof", tyn – the wandering word from OE tūn meaning "village, town".

Tolpinka, a river, rt of the Seym River, lt of the Desna and the village Tolpino at this river – Chuv. talpăn "to gush, fast flow".

Vandarets, a river, rt Svapa, rt of the Seym, lt of the Desna – Chuv. vantǎ "fish-trap", vantǎ yar "to put a fish-trap";

Voronezh, a city – Chuv. var "ravine", anăsh "width";

Yakhnovo, ten villages in several regions – Chuv. yam "manufacturing of tar"r".

Yam, thirteen villages in several regions – Chuv. yakhăn "close, near".

Yutsy, a village in Ostrovsky District, Pskov Oblast – Chuv. yüçĕ "swamp, bog"

|

BELARUS

In Belarus, one of the most widespread place names is Boyary, which is recorded for 37 settlements. It may come from the word boyare (singular boyaryn), which, according to some scholars, penetrated Old Church Slavonic from the language of the Danube Bulgars in the form bolarin (VASMER MAX. 1964: 203). However, the origin of this toponym and others like it can also be associated with the Chuv. payăr "proper, own". From the Proto-Turkic proto-form of this word come the German Bayern (the land of Bavaria), Bayreuth (the name of the city) and several Polish place names Bojary). There are no words with a similar root in either Polish or German. Polish words borrowed from Bulgars have the form bojarzy, bojarzyn. Thus, the name Boyarka, which is widespread in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus, may also be an ancient Turkic borrowing, and not come from the word boyar. In Belarus, the toponym Boyary is widespread in places where CWC sites and other place names of Turkic origin are absent. In such a place, it should not be such either, therefore it is not taken into account, and given the widespread use of later times, its origin is considered dubious.

The Turks as carriers of the CWC bypassed the territory of Belarus from the east and west since the road to the north was blocked by the marshy terrain of the Pripyat River basin. Nevertheless, there are many toponyms of ancient Yurkic origin in Northern Belarus. The Turks penetrated the country as carriers of the Estonian CWC and Fatyanovo culture. A separate variant of the CWC should have been formed here, the sites of which should be found near the following toponyms:

Basharovo, a village in Tolochin district of Vitebsk Region – Chuv. păchăr "grouse".

Bovshevo, a village in Dashkovka village council of Mogilev Region – Chuv pălkhav "mutiny, revolt".

Bulakhy, a village in Hlybokaye District of Vitebsk Region – Chuv. pulǎkh "fertility".

Buy, two villages in Vitebsk Region – Chuv.puy “to rich”.

Charkasy, three villages in Vitebsk Region, and villages in Minsk and Grodno Regions – Chuv. kĕr "autumn", kassă “settlement”.

Dashkovka, an agrotown in Mogilev District, Mogilev Region – Chuv tăshka "to mix".

Kalantayova, a village in Senno district of Vitebsk Region, Kolontai, a village in Volkovysk district of Grodno Region – See Kalantayiv.

Madora, a village in Kisteti village council of Rohachev district, of Gomel Region – Chuvash pagan names Mattur, Matur.

Orsha, a river and a town in Vitebsk Region – Chuv. ărsha "darkness, mirage".

Perki, a village in Kobrin District ofBrest Region – Chuv. pĕrke "envelop, wrap up".

Shalayouka, a village in Borovitsa village council of Kirovsk district, of Mogilev Region – Chuvash pagan name Shalay.

Sharshuny an agrotown in Minsk District, Minsk Region – Chuv. shărshă “smell”.

Shepelevka, a village in Maslaki village council of Horki district in Mogilev Region – Chuv. sheplĕ "strong, hard".

Soltanovo, an agrotown in Rechitsa district, of Gomel Region – Chuv saltăn "to unfold, untie, unwrap".

Tolpino, a village in Chashnyki district of Vitebsk Region – Chush. talpăn "to gush, spurt, flow rapidly".

Ula, a village and river in Beshenkovichi district of Vitebsk Region – Chuv. ula “motley”.

Voron'ky, a village in Miory district of Vitebsk Region Chuv. var "ravine", unkă "ring, round, encircling"

Yutski, a village in the Demidovichi village council of Dzyarzhynsk district in Minsk Region – Chuv. yüçĕ "swamp, bog".

The overview map of the Turkic placenames of ancient times.

On the map, purple dots mark localities with the Turkic origin of the name, which may correspond to the times of CWC or close to them. Maroon – the latter, of the Scythian period.

|

MOLDOVA

There are few place names of Turkic origin in Moldova. Almost all of them have correspondences in Ukraine (Bahmut, Odaia, Palanka, Şipoteni). Several toponyms of Măgura are typical for the Carpathian region (see below), and such decoding is accepted for others mentioned here :

Bahmut, a village, Călărași district – Chuv pakhmat – 1. «bold, reckless», 2. «intelligence, common sense».

Odaia, villages in Șoldănești and Niaporeni districs – Chuv ută 1. «hay». 2. «island». 3. «valley». ay «low, lowland», uy «field».

Palanca, a village, Drochia district – Chuv palan "guelder rosse", pălan "deer", adjective sufix -ka.

Şipoteni, a village, Hîncești district – Chuv shep "beautiful, wonderful", ută "valley", en "side".

|

ROMANIA

In Romania, all place names of alleged Turkic origin were left by the Bulgars that is Proto-Chuvashes in the middle of the 1st millennium when they moved to the Balkans. The most common here is Măgura. Only in Transylvania there are 97 (Haliczer Józef. 1935). If we talk about their origin, we can take into consideration the Slavic gora "mountain", but the prefix ма- is incomprehensible. Most likely, the form of toponyms of this type is a word related to Chuv. măkăr „hillock, cone” with ending –a taken under the influence of Slav. gora. The peoples of Dagestan, where the Khazar Khaganate once reigned, have a common word maghar "mountain", which has to but also of Bulgarish origin. Since this toponym has acquired a nominal sense (Rom. măgura "hillock"), out of all their many, it is almost impossible to single out the left by the Bulgars. Nevertheless, many of them are plotted on Google MY Maps in places where other Bulgarish toponyms are clustered. These can be considered the following:

Odaia, Odăile, There are place names of this type in Romania about ten – Chuv ută 1. «hay». 2. «island». 3. «valley». ay «low, lowland», uy «field».

Palanca, Pakanga, six place names of this type were found – Chuv palan "guelder rosse", pălan "deer", adjective sufix -ka.

Suceava, a city – чув. sět (Old Turc süt) «milk», shyvě «river».

Șipot, Șipote, Șipotu, eight villages have such names – – Chuv shep "beautiful, wonderful", ută "valley".

Tâmpa, a mountain in the city of Brașov – Сргм. tĕm "hill", pü "figure, body", "height, length."

Ţuţora, a village, Iași County – Chuv çiç «shine», «blossom», ăru «family, tribe».

|