The Urheimat of the Nostratic Languages

The term of Nostratic languages is used for the set of six large language families of the Old World: Altaic, Uralic, Dravidian, Indo-European, Kartvelian, and Semitic-Hamitic (or Afrasian) but it may also include other language families:

The boundaries for the Nostratian world of languages cannot yet be determined, but the area is enormous and includes such widely divergent races that one becomes almost dizzy at the thought (BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2018: 4).

In particular, according to A. Dolgopolsky, Chukchi-Kamchatkan, and Eskimo-Aleut languages can be classified as Nostratic. Later this idea was supported by Joseph Greenberg, and Bomhard suggested a kinship with Nostratic also of the Sumerian language(ibid: 5-7). In addition to these languages, he also refers to the Nostratic languages as Tyrrhenian, Gilyak (Nivkh), and Yukaghir (BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2014/2015, 20).

An in-depth study of the world's languages without taking into account the stratigraphy of individual lexical strata at the same time with false initial positions leads linguistics to a standstill. The fundamental mistake of many modern theorists from linguistics is the inclusion of all the so-called Altaiс languages, together with Turkic, in the Nostratic macro-family. Studies of the relationship between the Turkic languages by the graphic-analytical method (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998, 46-48) taking into account other facts, including data from archeology and toponymy, allowed us to find and justify the location of the ancestral home of the Turks in the Northern Azov Sea region between the Dnieper and Don rivers. Undoubted common features of all Altaic languages speak not of their kinship, but only of the affinity that arose as a result of cohabitation in the same territory after the migration of Turks to Altai, which entailed mutual borrowings, but mainly from Turkic, due to the higher level of development of their speakers (see the section Discussion).

The formation of the rest of the Altaic languages, as their study showed by the same method, took place in the basins of the left and right tributaries of the Amur River (see Far East: The Relationship of the Altaic and Türkic Languages). Their geographical location predetermined the presence of common linguistic elements in the Altai and Chukchi-Kamchatka languages. One has only to remove Turkic elements from all of them, as soon as everything falls into place. But few can dare to break with traditional ideas, especially not those who went out from the school of Sergei Starostin.

Of course, all languages of the world are related to each other, originating from one common language (STETSYUK VALENTYN. 2019: 1-28). However, they are related to different levels and represent a tree-like structure, and the branching of the tree allows us to talk about a greater kinship of languages belonging to smaller branches. In practice, this picture is distorted by contact with the languages of other families at different times and at different time intervals, as well as by longer staying in close proximity to some related languages compared to others. In the latter case, a greater similarity of languages gives reason to talk about their imaginary unity at an early stage, as is the case with the Slavic and Baltic languages. On the contrary, as a result of contact between the languages of different families, a phenomenon occurs when one of the languages has less ancestral, most ancient words than borrowed at a later time, what we can observe in the example of the Albanian language. When studying such languages, it is overlooked that the primordial words in the language are most used and thereby determine its attribution to a genetically related language family. This is exactly what the supporters of the kinship of the Turkic and Mongolian languages forget. An intuitive idea of the possibility of genetic kinship between individual language families appeared at the dawn of comparative linguistics without a clear idea of their relationship. Despite the fact that many striking similarities were found between Indo-European and some other languages, no convincing evidence of such a possibility was presented in the first works devoted to this topic. In general, the attitude of linguists to the idea of a comprehensive kinship of languages was skeptical, nevertheless, the many surprising facts of similarity between distant languages did not escape the attention of particularly insightful researchers. A fairly detailed narrative of the history of research leading to the idea of Nostratic languages can be found in a recent publication by еру mentioned American linguist (BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2018: 1-8), here we will briefly dwell on the emergence of interest in Nostratic languages in the Soviet Union.

At first a Nostratic theory was actively developed by a Moscow linguist V.M. Illich-Svitych based on the hypothesis of Holger Pedersen and Alfredo Trombetti. His first works on this topic were taken critically. Illich-Svitych analyzed and systematized similarities in word structure, grammar, and vocabulary of the Nostratic languages and gave a large volume of such matches between them in his book [ILLICH-SVITYCH V.M., 1971]. The scholar assumed that these similarities can be interpreted only within the theory postulating the genetic relationship of these languages i.e. that they are monophyletic and belong to one macrofamily (phylum) called Nostratic languages. Türkologists Gerard Clauson, Gerhard Doerfer, and Aleksander Shcherbak were the first numerous critics. Here is one of the evaluations of the work of Illich-Switych:

From the very beginning, all his efforts were focused on proving the Nostratic hypothesis and concrete languages were perceived through the prism of previously formulated correspondences [SHCHERBAK A.M. 1984: 35].

It should be noted that the sharpness of the evaluations was restrained by the ethical side of the question, which Sir G. Clauson noted specifically:

“It is always unpleasant to criticize the work of a scientist who has spent years of intensive work on its implementation, and it is doubly unpleasant when he is no longer there to protect himself. The enormous diligence and enthusiasm of V. M. Illich-Svitych evoke the deepest respect for him. It is a tragedy that they were spent on proving the truth of the situation, which probably cannot be true” [Quoted after SHCHERBAK A.M. 1984: 30]

V.M. Illich-Svitych was an outstanding personality and boldly took up a job that few would have dared. For this, he had both knowledge and character:

V.M. Illich-Svitych possessed an outstanding talent of a researcher, the abilities of a polyglot, an extraordinary working capacity, and the ability to soberly evaluate the results of his work. I can say with confidence that he took up the solution of the most difficult task of modern linguistics not from frivolity. It was organically alien to its nature. Illich-Svitych knew what awaited him, but he "was not afraid of deep water." Illich-Svitych began to seek an answer to the Nostratic hypothesis lonely. Only later was he joined by several capable students. [BERNSTEYN.B. 1986: 39).

New ideas are always perceived with difficulty. And, as always happens, over time, the attitude towards the Nostratic theory changed towards its recognition through the efforts of V. A. Dybo, who from the very beginning defended the idea of Illich-Switych. The main obstacle to the final recognition of the Nostratic theory is the assignment of Turkic languages to the Altai language family. This mistake entails others, such as the Chukchi-Kamchatkan and Eskimo-Aleut languages being classified as Nostratic. In general, the binary connections of languages classified as Nostratic, still remain insufficiently studied. However, even a superficial comparison of the vocabulary of pairs of Nostratic languages belonging to different linguistic families gives reason to take the issue of the existence of Nostratic languages enough seriously. If we talk, for example, about Turkic-Indo-European lexical correspondences, then in many cases, they look very convincing. Indo-European-Finno-Ugric correspondences are no less convincing, but they are often interpreted as borrowings from Indo-European in Finno-Ugric. Sometimes this is done, for example, following other researchers, by Kaisa Häkkinen in the etymological dictionary of modern Finnish (HĀKKINEN KAISA. 2007). To such borrowings, he refers the Finno-Ugric words with the meaning "bark" (Fin. kuori "bark, peel", Veps. kor' "bark", Erzya, Moksha kar' "bast shoe", Khanty hŏr "bark", Mansi kor- "tear bast"), "many, much" (Fin. moni, Est. mõni, Udm. mynda) and some others which have matches in the Indo-European languages. In other cases, Häkkinen refers to similar Indo-European and Finno-Ugric words to some indefinite common language. (for example PIE *aĝ- and PFU. *aja- "drive") or explains by early contacts between the Indo-European and Uralic linguistic communities (for example PIE nomn- and PFU *nime – both "name"). Finnish linguist refers to Nostratic only one word *kala "fish" (Fin. kala, Saam. guolli, Mari kol, Hung. hal a.o.). It is strange that when recognizing the existence of Nostratic languages in general, only one word was assigned to them from all Finno-Hungarian languages while ignoring other examples, some of which are obvious. For example, the similarity of the O.I. uda, Goth. watō, Slav. woda "water" and Fin. vesi, Mari wüt, Mok. ved' "the same" cannot be accidental, but more complex evidence of ancient kinship relations are possible too. One such evidence may be an etymological complex with the meanings of "pine", "fir", "galipot, soft resin", "pitch" (Lat. picea, Alb. pishе, Mok. pichi, Erz. piche "pine-tree", Ger. Fichte "fir-tree", Lat. picis, Gr. πισσα Fin. pihka, Est., Veps. pihk "soft resin", Rus., Ukr. peklo "hell" a.o.). On occasion, the similarity of Mansi and Khanty words to Germanic is explained by borrowing. Such borrowings can be considered possible when there is no definite idea of the location of the dissemination areas of certain languages in prehistoric times.

For the same reason, some Caucasian scholars are also critical of the inclusion of the Kartvelian languages into the Nostratic macrofamily, considering, for example, such words as Georg. ანკესი (anķesi) "fish hook", დრო (dro) "time", მკერდი (mķerdi) "breast", ნახვრეტი (naxvreti "hole", ფართო (parto) "wide", ფრთა (prta) "wing", "feather", Mingr. ლეტა (leţa) "clay" etc. simply by ancient borrowings from Proto-Indo-European. In other cases, borrowing from the Ossetian is assumed: Mingr. ნოსა (nosa), Laz. ნისა (nisa) "daughter-in-law, sister-in-law" (Osset. nostæ, PIE. *snusós), what is unlikely due to geographic and doubtful for phonetic reasons. Kartvelian-Finno-Ugric matches, such as. Georg. ფიჭვი pičvi "сосна" – Mok. piche "the same", Fin. pihka "soft resin"; Georg. ვერძი verdzi "ram" – Mok. veroz "lamb" and others are not considered as a Nostratic inheritance due to skepticism towards the Nostratic theory itself (KLIMOV G.A., KHALILOV M.Sh. 1994, 15 and further).

Without going into scientific disputes, I tried to analyze the already collected, processed, although not completely, systematized results of research by V. Ilyich-Svitych (ILLICH-SVITYCH V.M. 1971) using the graphic-analytical method. Let me remind you that the essence of the method is creating a graphical model of the kinship of languages belonging to the same language family on the basis of lexical-statistical data. A description of this analysis and the results obtained have been published in work devoted to the research on prehistoric ethnogenetic processes in Eastern Europe [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998: 27-36]. Here I will briefly present the final conclusion about the localization of the Urheimat of the Nostratic languages.

After processing all the materials of Ilyich-Svitych, supplemented by an insignificant amount of Andreev’s materials [ANDREYEV N.D. 1986], it turned out that out of 433 of the total number of language units (features), 34 are common, and the rest corresponded to 255 units from the Ural, also 255 units from the Altai, 253 units from the Indo-European, 240 – from the Semitic-Hamitic, 189 from the Dravidian and 139 from the Kartvelian. Then the number of mutual features in pairs of languages was calculated and the calculations gave the results presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Quantity of mutual features between language families.

| Altaic – Uralic | 167 | Uralic – Kartvelian | 66 |

| Altaic – Indo-European | 153 | Indo-European – Semitic-Hamitic | 147 |

| Altaic – Semitic-Hamitic | 149 | Indo-European – Dravidian | 108 |

| Altaic – Dravidian | 109 | Indo-European – Kartvelian | 70 |

| Altaic – Kartvelian | 84 | Semitic-Hamitic – Dravidian | 110 |

| Uralic – Indo-European | 151 | Semitic-Hamitic – Kartvelian | 86 |

| Uralic – Semitic-Hamitic | 136 | Dravidian – Kartvelian | 54 |

| Uralic – Dravidian | 134 |

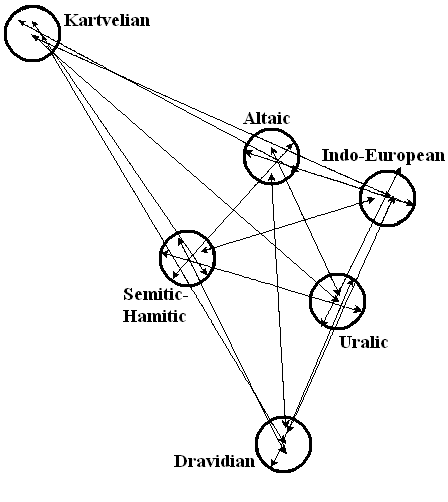

At first glance, there is no consistent pattern between these data, but it manifests itself if a graphical model of the relationship of the Nostratic languages is built on their basis. It is shown in Fig. 1. The description of the construction process is given in the section The Graphic-Analytical Method.. The very bringing of the initial data into a certain system, expressed in a fairly regular geometric figure, refutes the accusations of Illich-Svitych in a biased selection of material, because he, of course, did not expect such a result.

Fig. 1. The model of relationship of Nostratic languages.

As noted above, the Turkic language is not part of the Altaic language family, therefore the place of the Altaic languages in the scheme actually belongs to the Turkic ones. The presence of an insignificant number of features characteristic only of the Altai languages in the tables of Ilyich-Svitych could not significantly distort the kinship scheme.

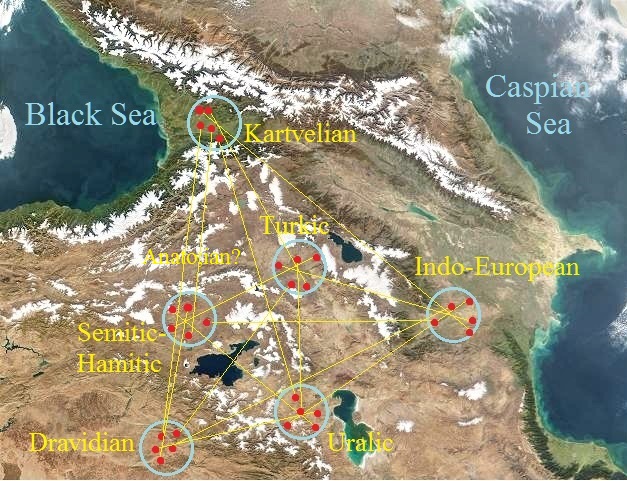

The next step was to search for the location of the resulting model on the map where there are areas limited by geographic boundaries. By the time the scheme was received, further habitats of Indo-Europeans, Finno-Ugrians, and Turks had already been localized in Eastern Europe. Having these data, and also taking into account the modern habitats of the speakers of the Afrasian languages (Africa, Western Asia), the Dravidian peoples (the south of the Indian subcontinent), and the speakers of the Kartvelian languages (the territory of Georgia and Lazistan in the northeast of Turkey) and the fact that the resulting scheme was quite compact, the search area could only be Western Asia. The idea of localizing the ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans in these places is not new, but it did not take into account one feature of the Indo-Europeans' glotto- and ethnogenesis.

Many researchers believed that the splitting of the Indo-European language took place in the ancestral home of its speakers and this made it difficult to find it since a comparison of various data led to mutually exclusive results. In this regard, the assumption arose that the formation of individual languages took place far from the ancestral home in a place that can be called the second ancestral home of the Indo-Europeans. According to Safronov, the hypothesis of the existence of two ancestral homelands, one of which was on the territory of the Armenian Highlands, and the other in the steppes of Eastern Europe, was put forward back in 1873 by a certain Miller, whose identity could not be established (SAFRONOV V.A., 1989: 23). According to T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov, the Indo-European community was "within the Middle East, most likely in the regions of the northern periphery of Western Asia, that is, south of Transcaucasia to Upper Mesopotamia" (GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V. .V., 1984: 890). However, they believed that the splitting of the Indo-European language took place in the same place.

During a detailed analysis of the geographical map of Western Asia, taking into account the obligatory presence of geographical limits, nothing suitable was found, except for the territory with the biblical Mount Ararat in the center around the three lakes Van, Sevan, and Urmia. The fact that the geographical boundaries are very well expressed here is evidenced by the presence of the state borders of six (h.e. very significant!) modern states on this territory. Three lakes form a regular triangle, on which the central part of our model is very well superimposed. But since the triangles are equilateral, the problem of choice arises. It was clear that the ancestors of the Dravidians would have to occupy an area somewhere in the south or east of the common territory

View Nostratic Urheimat in a larger map

Additional reasons for the choice were, firstly, the fact that modern Kartvelians, obviously, remained near their old habitat, and secondly, taking into account the possibility of movement of Indo-Europeans, Uralians, and Turks northward queues one after another without obstacles. If we had chosen the mirror version of the kinship scheme, then the Kartvelians had to populate the territory of the north of modern Azerbaijan in the spurs of the Greater Caucasus Range, which made it completely impossible for their contacts with the speakers of other Nostratic languages, because they would be separated by huge swamps in the lower reaches of the Araks and Kura rivers, which have largely remain to this day. True, these swamps would have made it difficult for the Indo-Europeans, Uralians, and Turks to move to Eastern Europe, but this was a one-time action that could be carried out by waterway along the Araks, and then through the Derbent passage to the Ciscaucasia. In addition, they could not move along the western coast of the Black Sea through swampy Colchis, because there is no convenient waterway there.

Thus, accepting our model, the Kartvelian predecessors populated the territory of what is nowadays Georgia, to the south from the Greater Caucasolists and partly Armenian highland in the Çoruh and the Upper Kura valley. The study of the ancient Kartvelian Indo-Europeanisms by Soviet Caucasian scholars well confirms the result obtained by the graphic-analytical method:

… I invariably defended the position on the autochthonousness of the Kartvels in Georgia, which was first consistently developed in Soviet science by G.A. Melikashvili (KLIMOV G.A. 1986: 159).

The cited author elsewhere argued that the area of the Indo-Europeans should be located near the Kartvelian one:

The material accumulated by the scientific tradition testifies that the Kartvelian language area was in contact with the area of dissemination of Indo-European speech from the earliest times (KLIMOV G.A. 1994: 206).

Klimov speaks of "contact", but in fact, between the Kartvelian and Indian-European areas, there was a Turkic one around Lake Sevan on the southern slopes of the Lesser Caucasus and, obviously, on the opposite bank of the Kura to the Agrydag ridge and to Mount Ararat. The Indo-European ancestral home was to the east, beyond the Zangezur ridge, possibly on the territory of modern Karabakh and on the right bank of the Araks to the swampy areas in the east and north. With such an arrangement of linguistic areas in the Kartvelian, Turkic, and Indo-European languages, there should be common lexical matches for them. For the Georgian words discussed above, they can be as follows:

ანკესი (anķesi) "hook" – PIE *ank- "to bend" – O.T. eŋ "to bend".

დრო (dro) "time" – Gr. ἁμαρτή "at the same time, simultaneously", O.Ind r̥tú-ḥ "certain time" (out of PIE. *ar- "to pass") – O.T. ertä "early, in the morning".

მკერდი (mķerdi) "breast" – Av. mǝrǝzāna "belly" (outof PIE *mak- "to swell") – O.T. baγīr "liver, heart".

ნახვრეტი (naxvreti) "hole" – PIE. *antro-m "cave, hole" – O.T. oŋuraj "to gape".

ფართო (prta) "wide" – O.Ind. práthati "to expand", (out of PIE. *plat "wide, flat") – O.T. bol "vast, wide", bulut "cloud".

ფრთა (prta) "wing" – O.Ind. páttra "wing, feather" (out of PIE *ptē – Chuv. părt "to flutter".

The ancestor of the Uralian peoples inhabited the area around Lake Urmia, and to the west of them behind the Kurdistan ridge around Lake Van lived Semitic-Khamites. To the south of both, on the slopes of the Khakyari mountains and the Kurdistan ridge in the basin of the Tigris, Big, and Small Zab rivers, the ancestors of the Dravids should have sat. Judging by this arrangement of the scheme and its very configuration (the Kartvelian area lies somewhat apart from the rest), some Nostratic language, except for the six considered, should have been formed near, in present-day Kars province of eastern Turkey. The further fate of the hypothetical speakers of this language remains unknown, but it can be assumed that the Anatolian languages developed from it, the speakers of which did not migrate to Europe, but populated in Asia Minor (See fig. 2)

Fig. 2. NASA space image of the cradle of humanity with the designated areas of formation of the Nostratic languages.

Obviously, the Nostratic parent language was dismembered not on six languages. We have to take into account also the Caucasian languages whose relationship with any language family has not yet been defined (or rather, they have not "fit into the common system"). After the publication of my work, where the Urheimat of the Indo-Europeans in the area of the three lakes was first reported (STETSYUK VALENTYN, 1998), I carried a study of Caucasian languages by the graphic-analytical method on materials of the project The Tower of Babel . The resulting models of these languages suggest that they were formed in the valleys of the Main Caucasus Range, ie ancestors of modern speakers of the Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestani language groups were aboriginal settlers of their present places. Their common language would be one of the oldest dialects of the Nostratic parent language whose speakers before all alienated from the common Paleolithic Nostratic tribe and settled in the southern and northern slopes of the Greater Caucasus, while the speakers of other six Nostratic languages still leave on three lakes area for a long time. With this assumption, we can think that by the time of the resettlement Nostratic groups in Europe, the slopes of the North Caucasus and steppes of the Caucasian plain were already inhabited by a native of Caucasian languages. Therefore, while their migration to East Europe the Indo-European, Uralic, and Türkic tribes had to move further northward.

The proposed localization of the Urheimat of the Nostratic languages could not go unnoticed in the scientific world, however, it did not find support, but also a critical assessment too. I tried to acquaint Russian scientists Sergey Starostin and Anna Dybo with my work but did find no understanding. Allan Bomhard believes that the attitude of some Russian scholars “tends to stifle progress in the study of distant-linguistic relationships among the languages/language families involved” [BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2021: 6]. I will say more: Russian linguistics is reactionary in its essence and serves the great power idea of Russian politics. My article describing the graph-analytical method on the material of the Slavic languages was ridiculed in an insulting tone, and I was presented as an amateur in linguistics [ZHURAVLEV A.F. 1991]. This reputation of mine is still maintained by Russian academic linguistics, having great influence in the scientific world.

On the other hand, a critical attitude to the dictionary of the Nostratic language compiled by Illich-Svitych gave rise to the belief that its analysis using the graphic-analytical method cannot provide reliable data. However, despite the critical attitude towards it, there was no fundamental analysis of it for 50 years. And finally, this task was undertaken by Bomgard who processed all three volumes of Illich-Svitycha's dictionary, while I only had access to the first one. In a recently published work (BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2021), he carefully considers 376 etymologies of the Illich-Svitych dictionary, of which, in his opinion, 167 have an erroneous etymology and are therefore rejected from consideration. In addition, from the list of remaining etymologies, he removes approximately eight dozen words included in it by mistake. Using his estimate, I reduced the list to 209 units, deleting as whole etymologists and individual erroneous words, and presented the resulting lexical material in the form of a dictionary table in the Excel editor. The table contains 122 Indo-European words, 116 Altaic, 111 Uralic, 108 Semitic-Hamitic, 103 Dravidian, and 63 Kartvelian words. The table format made it easy to calculate the number of common words in pairs of languages to use this data in graphical analysis. The calculation results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Quantity of mutual features between language families according to the corrected dictionary of the Nostratic language.

| Altaic – Uralic | 63 | Uralic – Kartvelian | 32 |

| Altaic – Indo-European | 63 | Indo-European – Semitic-Hamitic | 61 |

| Altaic – Semitic-Hamitic | 53 | Indo-European – Dravidian | 51 |

| Altaic – Dravidian | 58 | Indo-European – Kartvelian | 25 |

| Altaic – Kartvelian | 31 | Semitic-Hamitic – Dravidian | 56 |

| Uralic – Indo-European | 64 | Semitic-Hamitic – Kartvelian | 37 |

| Uralic – Semitic-Hamitic | 45 | Dravidian – Kartvelian | 28 |

| Uralic – Dravidian | 55 |

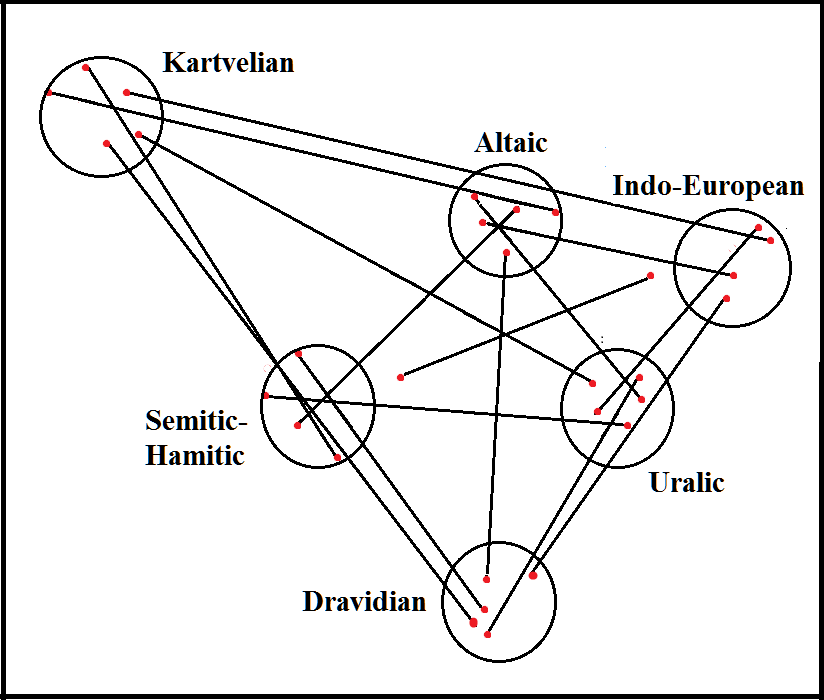

The new graphical model of the relationship of the Nostratic languages, built on the basis of these data, is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Fig. 4. The model of the relationship of the Nostratic languages according to the corrected dictionary of the Nostratic language.

As you can see, the new model retains the same configuration as the model built earlier on the uncorrected data. The following conclusions follow from this:

1. The configuration of the models graphically reflects the true relationship of Nostratic languages. This empirical generalization, according to Vernadsky, "does not differ from the scientifically established fact" (VERNADSKY V.I. 2004, § 15).

2. The graphic-analytical method allows for restoring the relationship of related languages on lexical material containing a significant number of non-systematic erroneous etymologies.

3. Bomhard's correction of the Illich-Svitych Nostratic dictionary contains a systematic error expressed in the unjustified excessive use of erroneous correspondences between Indo-European and Semitic-Hamitic languages. The dictionary contains words from the Indo-European languages more than others, which should correspond to the central position of the Proto-Indo-European language among all Nostratic ones. However, the connections of the Indo-European languages with other Nostratic contradict this assumption. Thus, Bomрard's lexical material cannot be considered a representative sample from the general set of lexical data from Nostratic languages. Accordingly, his idea of the composition of the Nostratic languages may be questioned.

The configuration of the relationship model of the Nostratic languages makes it possible to compose a representative sample of their vocabulary more accurately. If we have lexical correspondences between two languages whose areas do not have a common border, then there is a high probability that these languages had an intermediary in contacts whose language area lay between the areas of these two languages. As an example, let us give separate correspondences between the Indo-European and Dravidian languages, between the areas of which lies the area of the Uralic language.

Nostr. *Ḳarʌ ‘cliff, steep elevation’ has matches in IE *ker- ‘cliff, stone’ and Drav. *kar(a)- ‘bank, edge’. Fin kari 'underwater stone, rebble, sandbar' can also be included here.

Nostr. *Ḳurʌ ‘blood’ has matches in IE Indo-European *kreuH- ‘coagulated blood, bloody meat’ and Drav. *kuruti ‘blood’. Fin kura 'dirt, grime, or what's in a wound' can also be included here.

The Uralic and Turkic languages have much more common features in phonetics, morphology, and syntax than between them and the Indo-European languages. In phonetics primarily, the Turkic and Uralic languages bind vowel harmony, not clearly expressed in Indo-European. In the morphology, the distinguishing features of these are the lack of grammatical gender and the article, the declination using standard single-valued affixes, possessive declension by persons using the possessive suffixes, the availability of postpositions, and the absence of prepositions, no plural and dual number after numerals, and some other features. The syntax of these languages is different from the Indo-European in that the definition stands just before defining words, the possessive function is expressed in the forms of the verb "to be" rather than "to have" in Indo-European languages, the interrogative form of the sentence is reflected by a special particle and others.

Such abundance of common features between the Turkic and Uralic languages suggests that the Indo-Europeans left their ancestral home as the first when the ancestors of the Turks and Uralians remained in the Caucasus for a long time being neighbors and therefore kept together close language contact.

Another difference of the new model is the location of the Dravidian area closer to the center than it was in the first model, which reflects the increasingly close linguistic ties of the Dravidians with the parent Türkic and Uralic languages than the connection of these languages with parent Afrasian. Obviously speakers of this language first left their ancestral home, moving through the valley of the river Murat the Euphrates and further to the Arabian Peninsula, and, perhaps to Anatolia.

Recently, there has been a tendency to distinguish Afrasian languages as a separate macro-family and to exclude the Semitic-Hamitic from the Nostratic languages, which seems especially strange. The previously recorded ties of the Semitic-Hamitic languages with other Nostratic languages did not disappear anywhere, and those that caught the eye as the first should be the closest and related to the formation period. The fact that many African languages have many common elements with Semitic resembles the situation with Altai languages - the later numerous borrowings make us speak of close genetic kinship, while in fact there is an affinity.

If one tries to determine the time when the speakers of the six Nostratic languages began to leave their ancestral places for new habitats, one should remember that T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov include the first dialectal division of Indo-European languages, when the first dialects of the Anatolian languages arose, not later than IV mill. [GAMKRELIDZE T.V., IVANOV V.V. 1984: 861]. And then in their opinion, the Indo-Europeans moved to Europe around the Caspian Sea, and somewhere during this way, the Indo-Iranian group was separated from them.

T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov are considered authoritative experts on Indo-Europeistics, despite a thorough critique of their main work. Criticism has been rather pungent in some cases [MAŃCZAK WITOLD. 1991: 38], which is obviously talking about apparent contradictions in their theory. But the main objections are as follows:

1. No archaeological evidence exists to support this movement through Central Asia or along the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea [SAFRONOV V.A. 1989: 26].

2. Separation of the Indo-Iranian community from the majority of Indo-Europeans already in Asia Minor is contradicted by close contacts of the Indo-Iranian and Finno-Ugric languages in the IV mill. BC as Finno-Ugrians could not settle in the area south of the Caspian Sea. This contradiction of the hypothesis of T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov catches the eye immediately. According to E.E. Kuzmina:

T. Barrow, V.I. Abaev, J. Harmatta showed the antiquity of not only Iranian but also Indo-Aryan connections of Finno-Ugric languages. The attempt of T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov to give another interpretation of these facts was not supported by linguists [KUZMINA E.E. 1990: 33].

With the proven presence of the Indo-Iranian people in Eastern Europe Gamkrelidze and Ivanov's statement cannot be embedded in the chronological framework. Roamed from the Caucasus to Eastern Europe, they no doubt had to live here for quite some time, and then the speakers, at least, of the Indo-Aryan language had to come to Hindustan, which would be impossible if the Indo-Europeans began to settle in Europe in the IV millennium BC. For those times this would be really crazy pace, as it is generally believed that the migration rate was equal to one kilometer per year (ZBENOVICH V.G. 1989: 183).

Further research gives us reason to believe that the Indo-Europeans appear in Eastern Europe at the beginning of the 5th millennium BC, and the Urals and Turks several centuries later. Thus, we can conclude that the speakers of Nostratic languages should have stayed in Western Asia at most until the end of the 6th millennium BC, after which they began to settle in different directions.

The contradiction in the views of Gamkrelidze and Ivanov does not mean that the Urheimat of the Indo-Europeans was somewhere outside of Asia Minor, as it is understood by some scholars. Right, though not in all, have those who speak about two Indo-European Urheimat. One is defined in the Near East, and the second in Eastern Europe:

The territory of the Northern Black Sea region and the Volga region, including the Ural region, is regarded as the second ancestral home of the Indo-European community, namely: tribal carriers of ancient European dialects that came to this region with the Aryan tribes as a result of long-wave migrations from the region at the junction of Asia Minor and the Armenian Highlands (DOVZHENKO N.D., RYCHKOV N.A. 1988: 37).

Ambiguity is superfluous – the Indo-Europeans, as well as other ethnic groups, have the one Urheimat – and it's an area where the Indo-European parent language began to take shape. The later speakers of this parent language could move to other places, but there was the ancestral home of their descendants. H.Birnbaum expressed this most accurately:

And probably, if the main spreading space of the Nostratic language – as intended – should be really identified with the South Caucasus, the eastern (and southern) Anatolia, and the upper course of the Tigris and Euphrates, it is natural to assume that the later areas of the spread of the Proto-Indo-European language were closer to the Black Sea – the Pontic steppe areas in northern and western Anatolia…(BIRNBAUM H. 1993: 16).

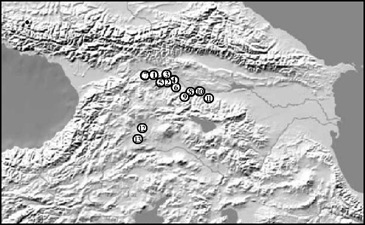

Future archaeological research can clarify the places of settlements of the Nostratic peoples on their Urheimat. For the present, the materials of Neolithic settlements in the South Caucasus were collected by an international team of archaeologists (see. Map below)

At left: Distribution of sites

attributed to the Šulaveri-Šomutepe

Group of the VI mil. BC in Southern Caucasus

According Svend Hansen, Guram Mirtschulava, Katrin Bastert-Lamprichs

1 Aruchlo I; 2 Šulaveri-Gora; 3 Imiris-Gora; 4 Gadachrilis-Gora; 5 Dangreuli-Gora; 6 Chramis Didi-Gora; 7 Mashaveras-Gora; 8 Šomutepe; 9 Toire Tepe; 10 Gargalar Tepesi; 11 Göytepe; 12 Artashen; 13 Aknashen- Khatunarkh (map: Vl. Ioseliani).

The map contains sites of the VI mill. BC. on the territory much smaller than that occupied by the Nostratic people, so it is impossible to say exactly to what time you need to refer their resettlement from the Urheimat. Clarification of this time can be made after the binding of archaeological cultures of Transcaucasia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe, that is, territories of their later habitats.

A general acquaintance with the works devoted to Nostratic languages allows us to say that the proof of the existence of such a macrofamily is carried out by inductive methods at the sophistic level. For example, Allan Bomhard does this when he cites general vocabulary, sound matches, and similarities of grammatical forms as proof (BOMHARD ALLAN R. 2018: 26-27). A great variety of examples from different languages are difficult to link together unless they are brought into a specific system, such as the use of the graphic-analytical method gives.

The best evidence of the existence of the Nostratic linguistic macrofamily is the location of the place of formation of the primary dialects of this family. As a result of this placement, we get a whole chain of mutually related deductive inferences that allow us to solve the fundamental problems of historical linguistics, such as, for example, the belonging of the Turkic languages to the Altaic family, ethnicity of the Corded Ware culture carriers, Cimmerians and Scythians, the mystery of the emergence of some states in Eastern Europe and others less significant.

It should be noted that not all speakers of the Nostratic languages had left their ancestral home. Further results of the research, as well as historical facts, suggest that while migration of peoples always some of them remains in the old place had no serious reason to go on a long journey.

The stay of Nostratic peoples on their Urheimat is considered more detailed in the section Southwest Asia as a Neolithic Cultural Center