Correlation Between the CWC Sites and Ancient Turkic Place-Names.

Preface

The importance of toponymy in restoring historical truth has not yet been appreciated by science. It is of great significance for archeology, which has virtually no written documents that can suggest where exactly research should be conducted and to whom the findings may belong. I will give a specific example. In the north of Belarus, there are many placenames of ancient Turkic origin. I associate the Corded Ware culture (CWC) with the ancient Turks. It is logical to assume that ancient Turkic toponymy should correlate with ancient Turkic culture. However, I have not found reliable evidence of the location of CWC sites in Northern Belarus, although its artifacts are occasionally found there. In search of more accurate information, I assumed that the Upper-Neman variant of the CWC is assumed precisely where ancient Turkic toponymy is widespread. Not to rely on random finds, excavations can be carried out where clusters of Turkic place names exist.

It is generally accepted that the Corded Ware Cultures (CWC) was created by the Indo-Europeans, who began settling across the vast expanse of Europe at the end of the 4th millennium BC from the steppes of the Northern Black Sea region. The steppe roots of the Central European population of Corded Ware culture have been confirmed by the results of ADNA research [WŁODARCZAK PIOTR. 2021: 435], however, they cannot say anything about its ethnicity. According to the widespread belief behind an archaeological culture, there is a certain anthropological type, but the language of its speakers is not taken into account. The population ethnicity is inherited by belonging to a particular language, which is seen in the example of the Turkic peoples. Their commonality is determined not by anthropological characteristics, but by the genetic relatedness of the languages spoken. Spiritual culture, which is less susceptible to borrowing than material culture, is therefore more stable. It is formed based on language and it is this that characterizes the ethnic group. Anthropology only adds a component to the definition of ethnicity.

A study of the related relationships of Indo-European and Turkic languages using a graphic-analytical method showed that the collapse of the Proto-Indo-European language took place in the Middle and Upper Dnieper basin, and the Proto-Turkic language in the territory between the Dnieper and Don Rivers [STETSYUK VALENTYN. 1998]. In this regard, it was suggested that the creators of the CWC were part of the ancient Turks, who, unlike their relatives, moved not to the east, but to the west and partially to the northeast [ibid: 66-67]

Toponymic materials were presented in support of this hypothesis, and in many cases, they were very convincingly etymologized using the Chuvash language. This language stands apart from other Turkic languages and there is reason to believe that it has preserved some elements of the Proto-Turkic language. The Proto-Turkic dialect from which Chuvash developed, was formed in the area on the left bank of the Dnieper, at its very mouth. That is, the ancestors of the Proto-Chuvashes were among those Turks who migrated to the West. Some of them remained in Western Ukraine for a long time, but at the beginning of the first millennium BC, they moved to the Black Sea steppes and went down in history as the Scythians. They spoke a language close to their paternal language. Their descendants, the Chuvashes, now dwell on the Upper Volga. It is because of its development, only the Chuvash language is the nearest of all the Turkic languages to the ancient Turkic language [STETSYUK V.M. 1999].

The etymology of place names is always probabilistic in, therefore arrays of place names have the evidentiary force and not individual examples. Moreover, data sets will be even more convincing if they form dense clusters or chains that reflect the migration routes of language speakers. Assuming that a dense cluster of place names in a certain place indicates it as a habitat. On the other hand, the habitat can be determined by the accumulation of homogeneous objects of material culture. If such habitats coincide sufficiently, then it can be argued that the creators of material culture were native speakers of the language with the help of which the place names located in the area of distribution of this culture are explained. At the same time, it is not at all necessary that the time of the emergence of place names corresponds to the time of the existence of the culture. The ethnicity of the population could not change when the culture changed. In our case, it may be that the Turks remained in their old habitat and founded their settlements when the CWC ceased to exist long ago.

It is in this way that we are trying to prove the Turkic ethnicity of the creators of CWC. For this purpose, the entire place names of Europe etymologized using the Chuvash language and the CWC sites were plotted on the same map in the Google My Maps database (see screenshot in Fig.1). Far beyond the ethnic territory of the Chuvash throughout Europe, about 1,200 place names have been etymologized.

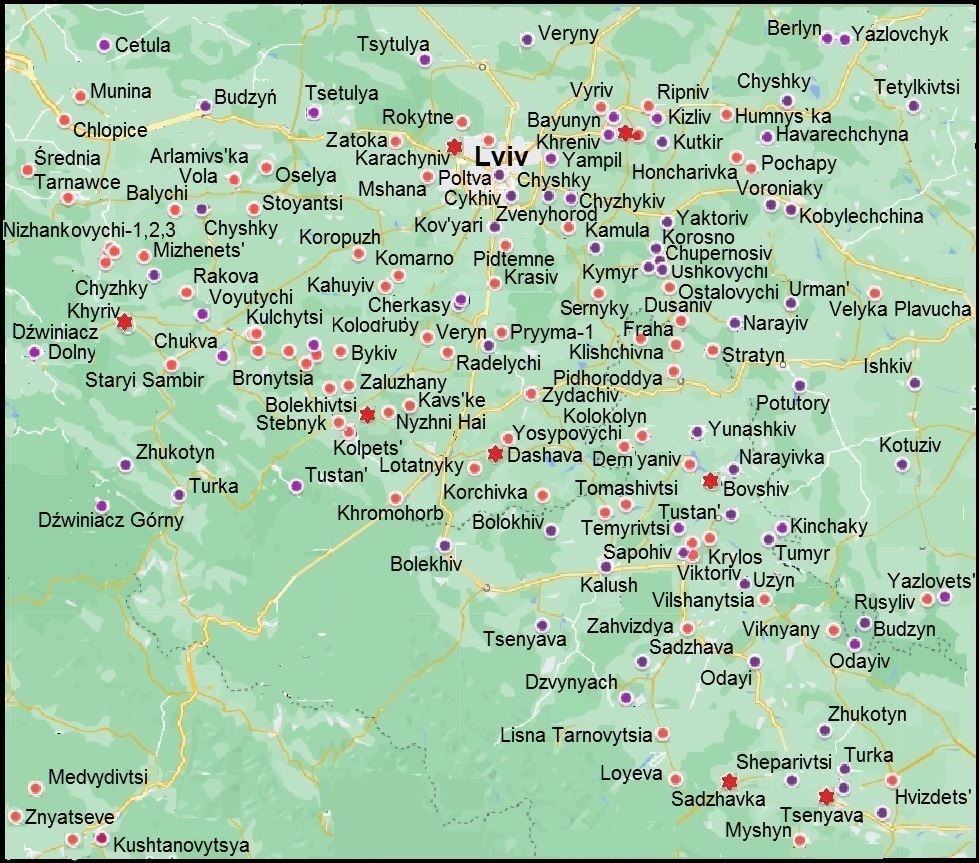

Fig. 1. The sites of CWC and Ancient Turkic place names

On the map, the icons in purple dots indicate the settlements with names of Turkic origin, which may correspond to the times of CWC or close to them. Asterisks mark known single or group sites of CWC.

The comparison of the distribution of Ancient Turkic place names and CWC sites showed that approximately one-fourth of them are located where CWC sites have not been found. Accordingly, they must be attributed to later times, mostly to the Scythian ones, since we identify the Scythians with the Proto-Chuvashes. However, 900 place names of supposed Turkic origin are a lot, even if some are erroneous. In total, we have the following premises:

1) The Corded Ware culture has roots in the Yamnaya culture, widespread in the steppes north of the Sea of Azov in the fourth – third millennium BC.

2) The ancient Turkic language broke up into dialects, from which individual Turkic languages eventually developed in the territory of the Sredny Stog culture, which preceded the Yamnaya culture in the fifth millennium BC.

3) Toponymy indicates that most of the Turks did not migrate to Asia, but remained in Europe, spreading over a vast territory. From these premises, the logical conclusion follows that the Corded Ware culture was created by the ancient Turks and spread by them throughout most of Europe. Let’s try to prove this once again.

Examining the map in Fig. 1, one can see that both CWC sites and Turkic place names form clusters of different sizes, and at the same time, these clusters partially coincide in some places. First, consider the region of Upper Dnieser, for which we have the most data [VOYTOVYCH MARIA. 2022]. Mrs. Maria compiled a list of 74 sites, of which 24 are settlements, the rest are barrows and ground burials. All of them were put on the map together with place names, which I deciphered with the help of the Chuvash language. Three or four sites from other sources were added to them (see the map in Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. The sites of CWC and Turkic place names in the Upper Dniester Region

On the map, the icons in purple dots indicate the settlements with names of Turkic origin, which may correspond to the times of CWC or close to them. Asterisks mark known single or group sites of CWC.

While etymologizing place names the following phonetic correspondences between the Ukrainian and Chuvash languages were revealed:

The letters ă and ě reflect reduced sounds a and e. In Ukrainian pronunciation, the sound ă can correspond to the vowels o, a, and less often u

Chuvash letter u correspond historically most often to sound a, seldom to u.

Chuvash letter a can correspond to Ukrainian a and o.

Chuvash letters e and i correspond to Ukrainian e and i though mutual substitutions are possible.

Chuvash consonants differ little from Ukrainian ones, but Chuvash previous sound k has evolved into x (kh) and g into k, that is, words with g don't exist in the Chuvash language do not, except for loan-words. Other features are:

Chuvash sound l in certain cases was reflected in Ukrainian as w.

Chuvash letters reflecting voiceless consonants may sound more voiced at the beginning of words and before vowels (for example, p sounds closer to b).

The letter ç reflects a sound close to the Ukrainian z' or c'. Because the voiceless consonants often have a voiced pair, then ç may also correspond to Ukrainian dz. Chuvash sound reflected by the letter č can be derived from the ancient Turkic t.

Banyunyn – Chuv. pan "apple tree" ("apple"?), yüně "cheap".

Bolekhiv – Chuv. pulǎx ”fertility”.

Bovshiv – Chuv. pălkhav "mutiny, revolt" . The CWC site.

Budzyn – Chuv. puçăn "to begin" or puç "start" + ăn "go well".

Cherkasy – Chuv. kĕr "autumn" (winter), kassă is the ezafe of kasă “street, neighborhood, quarter” (formerly “village”).

Chukva – Chuv. chukhlă "to make fit, know”.

Chupernosiv – Chuv. chăpar “motley”, masa “appearance”.

Chyshky – Chuv. chyshkă “fist”.

Chyzhky – Chuv. chyshkă “fist”.

Chyzhykiv – Chuv. chyshkă "fist”. The site of CWC

Dashawa – Chuv. tu “mountain” and shyvĕ “river”. Two СWС sites.

Dzvynyach – Chuv. çvin/çuyăn "catfish".

Dźwiniacz Górny – Chuv. çvin/çuyăn "catfish".

Havarechchyna, the village is famous for its special ceramic firing technology – Chuv kăvar "embers" and ěççynni "worker" united in kǎvarěççynni would mean "worker with hot coals".

Ishkiv – Chuv ĕshke "to knead, rumple".

Kahuiv – Chuv kăk "stump, root", uy «field».

Kamula, a mount – Chuv. kamǎr čul "cliff, block".

Khreniv – Chuv. khĕren "kite".

Khyriv, the town is in an area rich in pine forests – Chuv khyr "pine-tree". The site of CWC.

Kinchaky – Chuv. kanchăk “bag” or kănchăk “balled up”.

Kobylechchina – Chuv. khăpala "to burn", ěççynni "worker".

Korosno – Chuv. kărăs “poor, scanty” or karas "honeycomb".

Kotuziv – Chuv khutaç “sack, bag”.

Kov’yari – Chuv kăvar "embers".

Kutkir – Chuv kut “a trunk”, khyr “pine-tree”.

Kymyr – Chuv. kim “daughter-in-law”, yr, yră "good".

Narayiv – Chuv. nar "beautiful", ay "lowland".

Narayivka – like Narayiv.

Odayi – Chuvю utǎ 1. "hay". 2. "island". 3. "valley", ay "low, lowland".

Odayiv – like Odayi.

Ortynychi – Chuv. urtăn "to hang on, cling to".

Poltva, a river – Chuv. paltla, “rapid, fast".

Potutory – Chuv. păv “to press, squeeze”, tutăr “shawl”.

Sadzhava – Chuv sĕt "milk", shuvĕ "river".

Sapohiv – Chuv. sapak "bunch", "pod".

Sheparivtsi – Chuv. shǎpǎr “a besom”.

Sykhiv – Chuv. sykhă “watchful”.

Temyrivtsi – Chuv. timěr "iron". At CWC time, the word had a different meaning.

Tseniava – Chuv çěně “new”.

Tsetulya – Chuv çĕtü "cultivation of virgin land".

Turka – Chuv. turkhi "bidding".

Tustan’ – Old Chuv tuš "a stone", těm "hill".

Urman’, the village surrounded by forests – Chuv. vărman “forest".

Ushkovychi – Chuv. vyshkal, “similar”.

Uzyn – Chuv. uççăn "free, open, clear".

Veryn – Chuv. věrene "maple".

Voroniaky – Chuv. vyrăn "place" and yaka "smooth".

Voyutychi – Chuv. văy "force", ut «horse».

Yaktoriv – Chuv. yak "smooth" and tără “top".

Yampil – Chuv. yam "manufacturing of tar", păl "chimney".

Yazlovets’ – Chuv yăslav "noise, hubbub".

Yunashkiv – Chuv yunash "to place near".

Zhukotyn – Chuv çăka “linden”, OE tūn "village" was common among the population of Ukraine of different ethnicity.

These place names are arranged among CWC sites in such a way that they form a single field. The distribution density of those and others is approximately the same. Moreover, some place names together with CWC sites form a chain along the foot of the Carpathians, which is well viewed on Google My Maps (see screenshot in Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The path of movement of CWC creators to Central Europe marked by CWC sites and place names.

Obviously, this path, originally laid by the creators of the CWC, was subsequently used repeatedly, so the settlements along it could have been founded by the Turks, who remained in places convenient for living even later.

The density of CWC sites in this area is quite high, and is also noticeable in other places throughout the large expanse of Europe, which indicates the large number of creators of this culture. However the Turks themselves, as nomads, were not so numerous in contrast to the agricultural population of the Trypillian culture on the right bank of the Dnieper, where they began to cross at the end of the fourth millennium BC. Obviously, thanks to the militancy and better organization inherent in the nomads, they established a xenocracy regime over the Trypillians, imposing their own way of life and language on them. Thus, it can be assumed that the Trypillians were involved in the massive migration process of Turkic tribes.

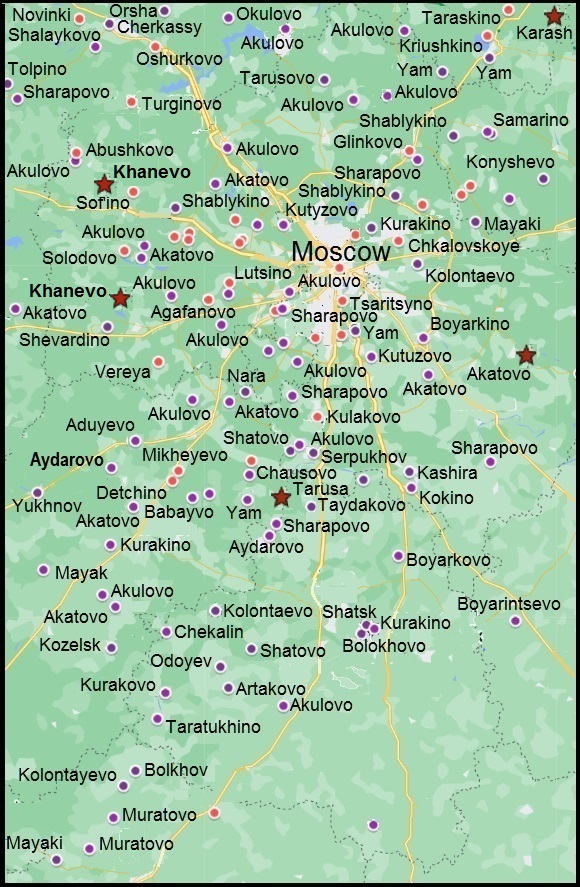

The same correlation between Turkic place names and CWC sites can be made in other places of their clusters. A good opportunity for this is provided for monuments of the Fatyanovo culture (FC), one of the variants of the CWC in the Moscow River catchment. Russian archaeologist Nikolai Krenke provided the data for this [KRENKE N.A. 2014]. I did the search and etymologization of Turkic place names in the nearby area using Chuvash.

Ukrainian archaeologists believe that the Fatyanovo culture has developed as a result of moving a part of the population of the Middle Dnieper culture to this territory at the beginning of its middle stages – in the end of the 3rd – beginning of the 2nd II mill [ARTEMENKO I.I. (Ed.) 1985, 375]. This assumption is confirmed by the chain of Turkic place names stretching along the Oka River valley from the area of distribution of the Middle Dnieper culture to the Moscow basin (see map in Fig. 4). The map shows the densest part of the cluster of sites along with the cluster of Turkic place names.

Fig. 4. The sites of FC and place names marking the migration of the Turks to the northeast.

On the map, FC sites are marked with red dots, Ancient Turkic place names with purple markers. Red asterisks indicate Turkic place names near which the CWC sites were found.

The interpretation of the Turkic place names shown on the map is given below.

Aduyevo (2) – Chuv. ută 1. "hay". 2. "island". 3. "valley', ay "low, lowland".

Akatovo (8) – Chuv. akatuy – mass celebration to mark the end of spring sowing.

Akulovo(15) – Chuv. akala "to plow" from aka "old plough".

Artakovo – Chuv. artak "bliss, caress".

Aydarovo (4) – Chuv. aytar "to reduce, decrease" or ay “low", tăr “to stand, become”.

Babayevo – Chuv. papay “old man, grandfather”.

Bolkhov – Chuv. pulăkh ”fertility”.

Bolokhovo – Chuv. pulăkh ”fertility”.

Boyarintsevo – Chuv. payăr "proper, own".

Boyarkino – Chuv. payăr "proper, own".

Boyarkovo – Chuv. payăr "proper, own".

Chausovo – Chuv. chăvash "Chuvash".

Chekalin – Chuv. chěkel "become beautiful"

Cherkasy – Chuv. kĕr "autumn", kassă “street, neighborhood, quarter” (formerly “village”).

Esukovskiy – Chuv. yüçеk "sour".

Karash – Chuv. karăsh "landrail, corncrake".

Kashira – Chuv. kăsh "sable", yĕr "track", "pathway".

Khanevo (2) – Chuv. khăna "guest", Tur. ev. The ancient Turkic name for the house has not been preserved in the Chuvash language, but it has been preserved in Turkish and Gagauz. It has taken the form öy in other Turkic languages.

Kokino – Chuv. kăk “root, stump”.

Kolontayevo (3) – Chuv. kălantay "slacker, lazy” (private message), khălin "stubborn", "slacker, lazy", -tay is an affix that forms adjectives from nominal stems with the meaning "possessing in excess the feature indicated in the stem" with a hint of contempt.

Konyshevo – Chuv. kănăsh "rubbish, garbage, trash".

Kurakino (3) – Chuv. kurăk "grass", "greens".

Kurakovo – Chuv. kurăk "grass", "greens".

Kutuzovo (2) – Chuv. khutaç “sack, bag”.

Mayak – Chuv. mayak "landmark".

Mayaki (2) – like Mayak (see).

Muratovo (2) – Old Chuv. bura (Chuv. pura) “frame, log house”, tu “do, biuld”.

Nara – Chuv. 1. nar «beautiful», 2. nără figuratively “bumpkin”.

Odoyev – Chuv. ută 1. "hay". 2. "island". 3. "valley". ay "low, lowland".

Okulovo – Chuv. akala "to plow" from aka "old plough".

Orsha – Chuv. ărsha "haze, sultry haze".

Samarino – Chuv. samăr "obesity, fatness".

Serpukhov – Chuv sĕr "to rub", pakhav "hobble".

Shablykino (2) – Chuv shăplăkh «stillness, lull».

Shalaykovo – Chuvash pagan name Shalay.

Sharapovo (9) – Chuv. shar "very, at al", apav is a word expressing surprise, joy.

Shatovo (2) – Сhuv shat "tight", "thickly".

Shevardino – Chuv. shĕvĕrt "to sharp".

Taratukhino – Chuv tara "hired labor", tukh "to begin, to become, to appear".

Tarusa (originally Torusa) – Chuv. tărăs "box of birch bark".

Tarusovo – like Tarusa.

Taydakovo – Chuv. tuy “wedding”, tăkă "rich".

Tolpino – Chuv. talpăn "to rush, spurt".

Yam (4) – Chuv yam “distillation of tar”.

Yukhnov – Chuv. yukhăn "decay, ruin, poverty".

As you can see from the list, the composition of toponyms is not diverse. For example, the name Akulovo (Okulovo) is placed on the map 16 times, out of a total of 34 such place names throughout the territory of the Fatyanovo culture. The name Akatovo is placed on the map 8 times out of 24 in this culture. Both of them are formed based on Chuv. aka “plow”, which speaks to the agricultural nature of the settlers. The place name of Sharapovo occurs 9 times out of 28 and can reflect the joy of migrants who discovered favorable conditions for settlement in the area. The semantics of these words give reason to make such an assumption. That part of the agricultural population of the Trypillian culture, assimilated by the Turks, migrated to the area of the Fatyanovo culture and was looking for an opportunity to continue their traditional occupation in new places. Livestock farming is reflected in four place names originating from Chuv. kurak "grass". Place names based on Chuv pulăkh correspond to fertile lands. The name Cherkasy is also related to livestock farming. It talks about the peculiarities of nomadic cattle breeding. This interpretation corresponds to the widespread Turkic word qyshlaq, which is translated as "wintering" (from the qysh "winter" of the same origin as the Chuv. kĕr). Turkic cattle breeders graze their cattle nomadically in the summer, and with the onset of autumn, they stop in one place, where they prepare hay for the winter in advance. Judging by the four place names Yam, making tar was a common craft. The tar was used to lubricate the axles of cartwheels, and this indicates the good development of vehicles, which greatly facilitated migration.

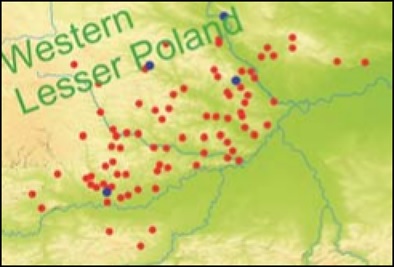

The main direction of migration of the Turks was western. Moving from the Upper Dniester Region, a large portion of them settled in the Krakow region, as evidenced by the concentration of archaeological finds from the final Eneolithic period (about 2800–2400 BC) [WŁODARCZAK PIOTR. 2021: 436]. Some of them are shown in Fig. 5

Fig. 5. Final Eneolithic grave sites in south-eastern Poland.

Fragment of the map [Ibid: Fig. 1].

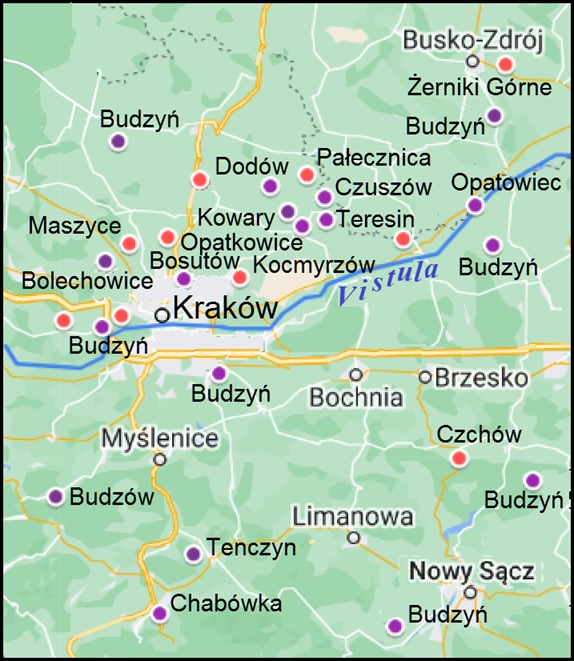

A small accumulation of supposed Turkic place names was found in the same area, which I interpreted using Chuvash. I posted them on Google My Maps along with my data about the CWC sites in this area (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Final Eneolithic grave sites marked red in south-eastern Poland and Ancient Turkic place names marked violet there

In total, 18 putative Turkic place names are shown on the map. The third part consists of the names Budzyń, of which four names have parts of a larger settlement. This name is compared with the Chuv. puçăn “to start, begin”. Migrants could give such and similar names to their first settlements in a new place. The remaining are:

Bosutów – Chuv. păs "steam", ută "island", "grove".

Budzów – Chuv. puç "head", puçăn "to start".

Budzowy – Chuv. puç "head", "start", "finish", "border", "side" etc.

Chabówka – Chuv. khapăl "hospitably".

Czuszów – Chuv. chukhă "poor, scanty".

Dodów – Chuv. tută "taste".

Kowary – Chuv kăvar “hot coal, embers”.

Leńcze – Chuv. lĕnche "to weaken, to become exhausted".

Opatkowice– Chuv. apat "food, nourishment, feed".

Paszkówka – Chuv. păshka "to pestle".

Tenczyn – Chuv. tĕnche "world, environment".

Teresin – Chuv. tĕrĕs "right, proper".

There are significantly more CWC sites in Germany than in Poland. And if we compare them with the Tutkic place names, then this is best done using the example of Bavaria, because this name in German Bayern can come from the Chuv. Chuv payăr «proper, own». Data on CWC sites were taken from the work of a German researcher of Corded Ware culture [HECHT DIRK. 2007]. They, together with place names of supposed Turkic origin, were placed on Google My Maps (see map in Fig. 7)

Fig. 7. The sites of CWC and Ancient Turkic place names in Bavaria.

On the map, CWC sites are marked with red dots and Turkic place names with purple markers. Red asterisks indicate the Turkic place names where the CWC sites were found.

On the map, the clusters of sites and place names coincide to a certain extent. This applies less to the southern part of Bavaria. Here, among the place names, Pullach “fertility” (8 cases) predominates. This name must refer to the agricultural population. It can be assumed that in this area the former pastoralists began to switch to an agricultural form of farming and this led to a change in culture. A chain formed by place names and sites running from Nuremberg to Passau marks the route of movement of the Turks. Due to the density of monuments, it is impossible to identify them all on a map scale. To get acquainted with them you need to look at the Google My Maps. Turkic roots are often an integral part of a place name, when German words Bach, Berg, Burg, Heim, Hof form the second part. The interpretation of some place names is very convincing, which is a good indication of the presence of the Turks in Bavaria, even if some etymologies are erroneous.

The clusters of CWC sites and place names coincide in Switzerland in the area of Zurich. A visible clearly on the map chain of Turkic toponyms leads from Munich to Zurich, marking the route of the movement of Turkic people from Bavaria to Switzerland:

Puchheim – Chuv. pukh "to gather".

Türkenfeld – OT türk "strong, mighty".

Pullach – Chuv. pulăkh "fertility".

Türkheim – OT türk "strong, mighty".

Erkheim – Chuv. yĕrk "order".

Aitrach – Chuv. ay "low", tărăkh "span, element".

Schurtannen – Chuv. shur "swamp", tăn "fumes, fog, haze".

Horgenzell – Chuv. khărkăn "to dry".

Salem – Chuv. selĕm "good, nice, beautiful".

It is significant that the road laid by the Turkic people at that time still exists under the number E96. Almost all the settlements mentioned lie along it. The complete list of the Turkic place names in Bavaria is given below:

Amerang – Chuv. amăr «time prone to rain», anka «thirsty».

Ascha – Chuv ăshă «warm».

Bamberg – Chuv pan «apple tree».

Bayreuth – Chuv payăr «own», ut «horse».

Berching – Chuv. pěrkhěn «to splash»

Dertingen – Chuv. těrt «push».

Dormitz – Chuv tărmăsh "wealth, goods, property".

Emersacker – Chuv. ĕmĕr «eternal», saкăr «eight».

Fürth – Chuv pürt «peasant house».

Gerbrunn – Chuv. kěr «autumn».

Happurg – Chuv. khap/a «body, figure, torso», parka «thick, strong».

Herpersdorf – Chuv. kherĕp «worries, burdens».

Homburg – Chuv. khăm «foetus of horse»

Iggenbach – Chuv. ikkěn «twain, double».

Iphofen – Chuv. ip «behoof, avail».

Irlbach – Chuv. ir «morning», -le adjective suffix.

Jachenau – Chuv. yakhăn «near».

Jachenhausen – Chuv. yakhăn «near».

Kasendorf – Chuv. kasăn «to be cutable».

Kemathen – Chuv. kem “decrease”, attan – word expressing desire.

Lam – Chuv. lăm «moisture, dampness, mildew»

Maiach – Chuv mayak «landmark».

Naila – Chuv. năyla «to drone, hum, buse».

Nürnberg (Nuremberg), a city – Chuv nür «moist, humid», en «side».

Perkam Chuv. pĕr «lonely, separate», kăm «ashes».

Pottenstein – Chuv. păttăm “spotted”.

Puchhof – Chuv. pukh «gather».

Puchheim – Chuv. pukh «gather».

Pullach (8) – Chuv. pulăkh «fertility».

Theres – Chuv. tĕrĕs «right».

Utzenhofen – Chuv. uççăn «free, open, clear».

Velden – Chuv. vĕlt «fast movement».

Vilseck – Chuv. vil «to die», sĕk «to butt».

Wittighausen – Chuv. vit “to cover”, tĕk “feather”, “hair”.

Wonsees – Chuv. vun «bundle of yarn».

Now let's return to the CWC sites in Northern Belarus. Very few have been found, but toponymy suggests that there should be significantly more of them. If we rely on toponymy data, the ancient Turks, bypassing the area of the Pripyat basin, moved north along two routes (see the map in Fig. 8). They spread the Middle Dnieper version of the CWC along the Dnieper. Several CWC sites mark this route which reaches the area of the Fatyan culture. A stream of Turks migrating to the Eastern Baltic entered Western Belarus. A chain of ancient Turkic toponyms from Volyn records one of the routes of movement of this stream to their accumulation in the present-day Pskov Region of Russia and in the north of Belarus. Some of them in order from south to north are given below:Similar work can be done for other variants of CWC and cultures previously considered such and dating back to a later time. The correlation of sites and place names does not indicate their attribution to the same archaeological culture, but only the long-term presence of the Turks in a large area of Europe for a long time.